[Editor’s Note: Army Mad Scientist is pleased to present our latest episode of The Convergence podcast, featuring guest panelists Ian Sullivan, Mitchell Land, LTC Peter Soendergaard, Jennifer McArdle, Becca Wasser, Dr. Stacie Pettyjohn, Sebastian Bae, Dan Mahoney, and Jeff Hodges discussing how wargaming enhances Professional Military Education (PME), hones cognitive warfighting skills, and broadens our understanding of future Operational Environment possibilities — Enjoy!]

[If the podcast dashboard is not rendering correctly for you, please click here to listen to the podcast.]

Army Mad Scientist interviewed the following world-class SMEs to explore how wargaming can enhance traditional training and education methods to help build better Leaders:

Ian Sullivan serves as the Senior Advisor for Analysis and ISR to the Deputy Chief of Staff, G-2, at the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC G-2). This is a Tier One Defense Intelligence Senior Level (DISL) position. He is responsible for the analysis that defines and the narrative that explains the Army’s Operational Environment, which supports integration across doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership and education, personnel, facilities, and policy. Mr. Sullivan is a career civilian intelligence officer who has served with the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI); Headquarters, U.S. Army Europe and Seventh Army, Deputy Chief of Staff, G-2 (USAREUR G-2); and as an Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) cadre member at the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC). Prior to assuming his position at the TRADOC G-2, Mr. Sullivan led a joint NCTC Directorate of Intelligence/Central Intelligence Agency Counterterrorism Mission Center unit responsible for Weapons of Mass Destruction terrorism issues, where he provided direct intelligence support to the White House, senior policymakers, Congress, and other senior customers throughout the Government. He was promoted into the Senior Executive ranks in June 2013 as a member of the ODNI’s Senior National Intelligence Service, and transferred to the Army as a DISL employee in January 2017. Mr. Sullivan is also a frequent and valued contributor to the Mad Scientist Laboratory.

Ian Sullivan serves as the Senior Advisor for Analysis and ISR to the Deputy Chief of Staff, G-2, at the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC G-2). This is a Tier One Defense Intelligence Senior Level (DISL) position. He is responsible for the analysis that defines and the narrative that explains the Army’s Operational Environment, which supports integration across doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership and education, personnel, facilities, and policy. Mr. Sullivan is a career civilian intelligence officer who has served with the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI); Headquarters, U.S. Army Europe and Seventh Army, Deputy Chief of Staff, G-2 (USAREUR G-2); and as an Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) cadre member at the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC). Prior to assuming his position at the TRADOC G-2, Mr. Sullivan led a joint NCTC Directorate of Intelligence/Central Intelligence Agency Counterterrorism Mission Center unit responsible for Weapons of Mass Destruction terrorism issues, where he provided direct intelligence support to the White House, senior policymakers, Congress, and other senior customers throughout the Government. He was promoted into the Senior Executive ranks in June 2013 as a member of the ODNI’s Senior National Intelligence Service, and transferred to the Army as a DISL employee in January 2017. Mr. Sullivan is also a frequent and valued contributor to the Mad Scientist Laboratory.

Mitchell Land has spent time in both the Navy and the Army National Guard, and has a life-long love affair with gaming war. He is the designer of GMT’s Next War games. The series currently consists of five games (two of which are 2nd Editions) and three supplements, with more on the way. In addition, Mr. Land was the developer for GMT’s Silver Bayonet: The First Team in Vietnam (25th Anniversary Edition) and Caesar: Rome vs Gaul. When not playing or working on games, you can find him cycling — most often on the Katy Trail.

Mitchell Land has spent time in both the Navy and the Army National Guard, and has a life-long love affair with gaming war. He is the designer of GMT’s Next War games. The series currently consists of five games (two of which are 2nd Editions) and three supplements, with more on the way. In addition, Mr. Land was the developer for GMT’s Silver Bayonet: The First Team in Vietnam (25th Anniversary Edition) and Caesar: Rome vs Gaul. When not playing or working on games, you can find him cycling — most often on the Katy Trail.

LTC Peter Soendergaard is an Infantry officer in the Royal Danish Army. He has served in both Iraq and Afghanistan. For the last ten years, he has worked in various force development positions, from the Danish Army’s Maneuver Center of Excellence to the Army Staff. For the past four years, LTC Soendergaard has served as the Danish Army’s liaison officer to U.S. Army TRADOC. He is currently serving in the strategic development section of the Danish Defense Command.

LTC Peter Soendergaard is an Infantry officer in the Royal Danish Army. He has served in both Iraq and Afghanistan. For the last ten years, he has worked in various force development positions, from the Danish Army’s Maneuver Center of Excellence to the Army Staff. For the past four years, LTC Soendergaard has served as the Danish Army’s liaison officer to U.S. Army TRADOC. He is currently serving in the strategic development section of the Danish Defense Command.

Jennifer McArdle is the Head of Research at Improbable U.S. Defense & National Security, a commercial start-up that is bringing innovative distributed simulation technology to defense. She also serves as an Adjunct Senior Fellow in the Center for a New American Security’s defense program and wargaming lab and as a Non-Resident Fellow at the Joint Special Operations University. A former professor, Ms. McArdle has served on Congressman Langevin’s cyber advisory committee and as an expert member of a NATO technical group that developed cyber effects for the military alliance’s mission and campaign simulations. Ms. McArdle is a PhD candidate at King’s College London in War Studies, is the recipient of the RADM Fred Lewis (I/ITSEC) doctoral scholarship in modeling and simulation, and is a Certified Modeling and Simulation Professional (CMSP). She is a term member with the Council on Foreign Relations. Ms. McArdle is also a frequent and valued contributor to the Mad Scientist Laboratory and The Convergence podcast.

Jennifer McArdle is the Head of Research at Improbable U.S. Defense & National Security, a commercial start-up that is bringing innovative distributed simulation technology to defense. She also serves as an Adjunct Senior Fellow in the Center for a New American Security’s defense program and wargaming lab and as a Non-Resident Fellow at the Joint Special Operations University. A former professor, Ms. McArdle has served on Congressman Langevin’s cyber advisory committee and as an expert member of a NATO technical group that developed cyber effects for the military alliance’s mission and campaign simulations. Ms. McArdle is a PhD candidate at King’s College London in War Studies, is the recipient of the RADM Fred Lewis (I/ITSEC) doctoral scholarship in modeling and simulation, and is a Certified Modeling and Simulation Professional (CMSP). She is a term member with the Council on Foreign Relations. Ms. McArdle is also a frequent and valued contributor to the Mad Scientist Laboratory and The Convergence podcast.

Becca Wasser is a Fellow in the Defense Program and lead of the Gaming Lab at the Center for a New American Security. Her research areas include defense strategy, force design, strategic and operational planning, force posture and employment, and wargaming. Prior to joining CNAS, Ms. Wasser was a senior policy analyst at the RAND Corporation, where she led research projects and wargames for the Department of Defense and other U.S. Government entities. She holds a BA from Brandeis University and an MS in foreign service from the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University.

Becca Wasser is a Fellow in the Defense Program and lead of the Gaming Lab at the Center for a New American Security. Her research areas include defense strategy, force design, strategic and operational planning, force posture and employment, and wargaming. Prior to joining CNAS, Ms. Wasser was a senior policy analyst at the RAND Corporation, where she led research projects and wargames for the Department of Defense and other U.S. Government entities. She holds a BA from Brandeis University and an MS in foreign service from the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University.

Dr. Stacie Pettyjohn is a Senior Fellow and Director of the Defense Program at the Center for a New American Security. Her areas of expertise include defense strategy, posture, force planning, the defense budget, and wargaming. Prior to joining CNAS, Dr. Pettyjohn spent over 10 years at the RAND Corporation as a political scientist. Between 2019–2021, she was the director of the strategy and doctrine program in Project Air Force. From 2014–2020, she served as the co-director of the Center for Gaming. In 2020, she was a volunteer on the Biden administration’s defense transition team. She has designed and led strategic and operational games that have assessed new operational concepts, tested the impacts of new technology, examined nuclear escalation and warfighting, and explored unclear phenomena, such as gray zone tactics and information warfare. Previously, she was a research fellow at the Brookings Institution, a peace scholar at the United States Institute of Peace, and a TAPIR fellow at the RAND Corporation. Dr. Pettyjohn holds a PhD and an MA in foreign affairs from the University of Virginia and a BA in history and political science from the Ohio State University.

Dr. Stacie Pettyjohn is a Senior Fellow and Director of the Defense Program at the Center for a New American Security. Her areas of expertise include defense strategy, posture, force planning, the defense budget, and wargaming. Prior to joining CNAS, Dr. Pettyjohn spent over 10 years at the RAND Corporation as a political scientist. Between 2019–2021, she was the director of the strategy and doctrine program in Project Air Force. From 2014–2020, she served as the co-director of the Center for Gaming. In 2020, she was a volunteer on the Biden administration’s defense transition team. She has designed and led strategic and operational games that have assessed new operational concepts, tested the impacts of new technology, examined nuclear escalation and warfighting, and explored unclear phenomena, such as gray zone tactics and information warfare. Previously, she was a research fellow at the Brookings Institution, a peace scholar at the United States Institute of Peace, and a TAPIR fellow at the RAND Corporation. Dr. Pettyjohn holds a PhD and an MA in foreign affairs from the University of Virginia and a BA in history and political science from the Ohio State University.

Sebastian Bae is a research analyst and game designer at CNA’s Gaming & Integration program, and works in wargaming, emerging technologies, the future of warfare, and strategy and doctrine for the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps. He also serves as an adjunct assistant professor at the Center for Security Studies at Georgetown University, where he teaches a graduate course on designing educational wargames. He has taught similar courses at the U.S. Naval Academy and the U.S. Marine Corps Command & Staff College. He is also the faculty advisor to the Georgetown University Wargaming Society, the Co-Chair of the Military Operations Research Society Wargaming Community of Practice, and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Brute Krulak Center for Innovation and Creativity. Previously, he served six years in the Marine Corps Infantry, leaving as a Sergeant. He deployed to Iraq in 2009.

Sebastian Bae is a research analyst and game designer at CNA’s Gaming & Integration program, and works in wargaming, emerging technologies, the future of warfare, and strategy and doctrine for the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps. He also serves as an adjunct assistant professor at the Center for Security Studies at Georgetown University, where he teaches a graduate course on designing educational wargames. He has taught similar courses at the U.S. Naval Academy and the U.S. Marine Corps Command & Staff College. He is also the faculty advisor to the Georgetown University Wargaming Society, the Co-Chair of the Military Operations Research Society Wargaming Community of Practice, and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Brute Krulak Center for Innovation and Creativity. Previously, he served six years in the Marine Corps Infantry, leaving as a Sergeant. He deployed to Iraq in 2009.

Dan Mahoney is the Chief of the Campaign Wargaming Division at the Center for Army Analysis (CAA). Mr. Mahoney was an ROTC Cadet at Lehigh University and spent 23 years as an Infantry officer in the Army, retiring as a Lieutenant Colonel. He taught at the United States Military Academy at West Point before attending the School of Advanced Military Studies, becoming the Chief of Plans for the 1st Cavalry Division, and eventually founding the Campaign Wargaming Division at CAA.

Dan Mahoney is the Chief of the Campaign Wargaming Division at the Center for Army Analysis (CAA). Mr. Mahoney was an ROTC Cadet at Lehigh University and spent 23 years as an Infantry officer in the Army, retiring as a Lieutenant Colonel. He taught at the United States Military Academy at West Point before attending the School of Advanced Military Studies, becoming the Chief of Plans for the 1st Cavalry Division, and eventually founding the Campaign Wargaming Division at CAA.

Jeff Hodges is the educational lead at the U.S. Army Modeling and Simulation School (AMSS) at Ft. Belvoir, VA. He designs and implements courses at AMSS to ensure that the FA57 and CP36 workforce can fully support the Commander’s readiness objectives by building awareness, building a Common Operating Picture (COP), and building tough and realistic simulations, tabletop exercises, and wargames that facilitate staff understanding, education, and training.

Jeff Hodges is the educational lead at the U.S. Army Modeling and Simulation School (AMSS) at Ft. Belvoir, VA. He designs and implements courses at AMSS to ensure that the FA57 and CP36 workforce can fully support the Commander’s readiness objectives by building awareness, building a Common Operating Picture (COP), and building tough and realistic simulations, tabletop exercises, and wargames that facilitate staff understanding, education, and training.

In today’s podcast, our panel of SMEs address how wargaming can enhance Professional Military Education (PME), hone cognitive warfighting skills, and broaden our understanding of future Operational Environment possibilities. The following bullet points highlight key insights from our interview:

-

-

- Learning from Wargaming can be broken down into two categories: discovery/analytic and experiential. Both categories are important but have different end-goals. Discovery/analytic wargaming helps one develop new insights or better understand some type of phenomena (e.g., concept or capability development). Experiential wargaming supports training and education and is designed to instill best practices, lessons learned, and develop creativity and agility among future leaders. Wargaming allows players to transcend their current realities and build cognitive warfighting proficiencies.

-

-

-

- Experiential learning leads to far higher learning retention than traditional passive methods of instruction, such as classroom-based lectures. It allows individuals to follow their ideas, work through problems as they arise, experience failure in a safe environment, and ultimately learn how to overcome challenges.

-

-

-

- The key to a successful wargame is an informed, accurate, and thinking adversary. It is vital that the Red Cell depicts an adversary as close to reality as possible, providing players with the best opportunities to learn about adversarial tactics and capabilities, decision-making, and thought-processes.

-

-

-

- Wargaming is used extensively at different levels in the Army — to explore ideas, look at alternatives, and think about the future, but also to test concepts and capabilities. Wargaming formats range from traditional table top board games, to discussion-based exercises, to computerized simulations that provide players with a realistic, immersive environment to visualize the fight.

-

-

-

- Designing an effective and successful wargame is dependent on one’s focus and learning demands. Designers should start the process by identifying the goal(s) that they want to accomplish and then work backwards. Carefully selecting the correct tools and technology to support players achieving the end-goal(s) is pivotal to eliciting the desired learning outcome.

-

-

-

- While wargaming can provide an accurate and realistic representation of a real-world adversary’s tactics, techniques, and procedures, it can also uncover unexpected TTPs that our forces may not have anticipated. Encountering these actions in the game allows players to develop and implement courses of action in a consequence-free environment, helping them to avoid operational surprise on the battlefield, while building confidence in their ability to successfully overcome it when it inevitably occurs.

-

-

-

- The future of wargaming will likely be more technology-heavy, interactive, distributed, and realistic while still having a significant amount of traditional and manual games. Learning goals can be achieved via both conventional (e.g., table top) wargaming and immersive simulations employing emergent technologies. Regardless of the media, some posit that the golden age of wargaming is coming to an end, as there is a dearth of young talent in the pipeline to replace the old guard.

-

Stay tuned to the Mad Scientist Laboratory for our next episode of The Convergence, featuring Zach Schonbrun, journalist and author of The Performance Cortex: How Neuroscience is Redefining Athletic Genius . We’ll talk with Zach about his book, how the brain — not the body — may be responsible for athletic prowess, and the implications for future Soldiers.

Stay tuned to the Mad Scientist Laboratory for our next episode of The Convergence, featuring Zach Schonbrun, journalist and author of The Performance Cortex: How Neuroscience is Redefining Athletic Genius . We’ll talk with Zach about his book, how the brain — not the body — may be responsible for athletic prowess, and the implications for future Soldiers.

If you enjoyed this post, explore the TRADOC G-2‘s Operational Environment Enterprise web page, brimming with information on the Operational Environment and our how our adversaries fight to enhance the reality of your wargaming experience…

…. and check out the following Army Mad Scientist wargaming-related content:

Would You Like to Play a Game? Wargaming as a Learning Experience and Key Assumptions Check and “No Option is Excluded” — Using Wargaming to Envision a Chinese Assault on Taiwan, by Ian Sullivan

Using Wargames to Reconceptualize Military Power, by proclaimed Mad Scientist Caroline Duckworth

A New American Way of Training and associated podcast, with Jennifer McArdle

From Legos to Modular Simulation Architectures: Enabling the Power of Future (War) Play, by Jennifer McArdle and Caitlin Dohrman

The Storm After the Flood virtual wargame scenario, video, notes, and Lessons Learned presentation and video, presented by proclaimed Mad Scientists Dr. Gary Ackerman and Doug Clifford, The Center for Advanced Red Teaming, University at Albany, SUNY

The Metaverse: Blurring Reality and Digital Lives with Cathy Hackl and associated podcast

Gamers Building the Future Force and associated podcast

Fight Club Prepares Lt Col Maddie Novák for Cross-Dimension Manoeuvre, by now COL Arnel David, U.S. Army, and Major Aaron Moore, British Army, along with their interview in The Convergence: UK Fight Club – Gaming the Future Army and associated podcast

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

Researchers have long called for a reinvention of the way we

Researchers have long called for a reinvention of the way we  overestimated the Afghans’ will to fight, underestimated the Ukrainians’ will to fight.” As the United States monitors an increasingly assertive and

overestimated the Afghans’ will to fight, underestimated the Ukrainians’ will to fight.” As the United States monitors an increasingly assertive and 500,000 total military personnel compared to Russia’s 1,350,000. The Ukrainian military was also

500,000 total military personnel compared to Russia’s 1,350,000. The Ukrainian military was also  significantly contribute to U.S. mission success. Historically, too, the U.S. military has had the

significantly contribute to U.S. mission success. Historically, too, the U.S. military has had the

Wargames

Wargames In a wargame simulating a

In a wargame simulating a

COL John Antal

COL John Antal

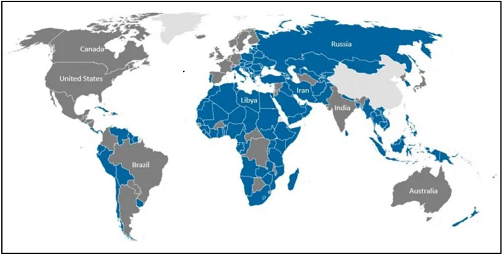

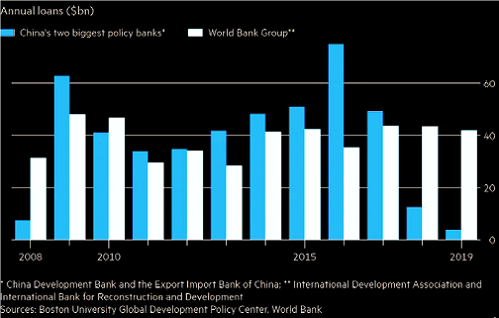

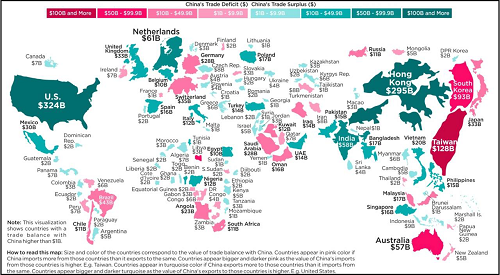

Lt. Col. Stacy N. Slate (USAF), and LTC Andrew J. Wiker (USA). Their requirement synthesized and analyzed open-source documents to answer the following question: How can China meet its national objectives to become the world’s dominant power by 2049? Read on to learn what our most recently proclaimed Mad Scientists say about how our

Lt. Col. Stacy N. Slate (USAF), and LTC Andrew J. Wiker (USA). Their requirement synthesized and analyzed open-source documents to answer the following question: How can China meet its national objectives to become the world’s dominant power by 2049? Read on to learn what our most recently proclaimed Mad Scientists say about how our

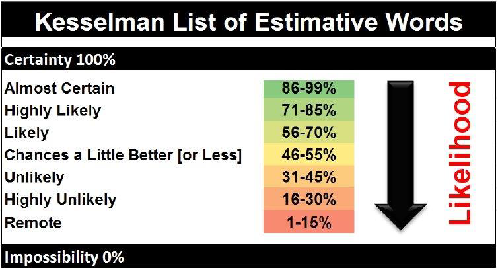

Finally, Xi Jinping is highly likely to continue building alliances in the Indian Ocean through the BRI. Dual civil/military port projects in Pakistan, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka allow the PLA-Navy to isolate its regional geopolitical competitor, India, militarily. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor project, connecting western China directly to the Indian Ocean shipping lanes through Pakistan’s Gwadar Port with pipelines, railroads, and roads, is likely economically unviable.

Finally, Xi Jinping is highly likely to continue building alliances in the Indian Ocean through the BRI. Dual civil/military port projects in Pakistan, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka allow the PLA-Navy to isolate its regional geopolitical competitor, India, militarily. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor project, connecting western China directly to the Indian Ocean shipping lanes through Pakistan’s Gwadar Port with pipelines, railroads, and roads, is likely economically unviable.  Still, the geopolitical benefit outweighs the cost if the isolation forces India to reach an accommodation with China and downgrade its relationship with the US.

Still, the geopolitical benefit outweighs the cost if the isolation forces India to reach an accommodation with China and downgrade its relationship with the US.

Dr. Mica Hall

Dr. Mica Hall