[Editor’s Note: As Russia enters the 141st day of its “Special Military Operation” in Ukraine, Mad Scientist Laboratory reviews previous posts and podcasts to synopsize what this conflict is telling us about the Operational Environment and the changing character of warfare. This is especially timely, given that the U.S. Army is finalizing its draft FM 3-0, Operations, laying out our future multidomain operations warfighting doctrine, and preparing to implement the Army’s greatest modernization effort since the Big Five four decades ago.

Much as the Russo-Japanese War augured the Great War, and the Spanish Civil War foreshadowed the Second World War, lessons from the current Russia-Ukraine Conflict can inform us how future conflicts in the mid-twenty first century may be fought and won (or lost!).  Regular readers will recall our Other People’s Wars: The US Military and the Challenge of Learning from Foreign Conflicts post and podcast last fall with Dr. Brent L. Sterling, who reminded us that learning from foreign wars can be a challenging endeavor. Findings frequently run counter to deeply-rooted institutional biases, and Services’ culture and bureaucratic politics can limit the implementation of lessons learned from other nations’ conflicts. Dr. Sterling admonishes us, however, to remember that other powers are also observing and learning from foreign conflicts. We ignore these “sign posts to the future” at our future peril — Read on!]

Regular readers will recall our Other People’s Wars: The US Military and the Challenge of Learning from Foreign Conflicts post and podcast last fall with Dr. Brent L. Sterling, who reminded us that learning from foreign wars can be a challenging endeavor. Findings frequently run counter to deeply-rooted institutional biases, and Services’ culture and bureaucratic politics can limit the implementation of lessons learned from other nations’ conflicts. Dr. Sterling admonishes us, however, to remember that other powers are also observing and learning from foreign conflicts. We ignore these “sign posts to the future” at our future peril — Read on!]

In Through Soldiers’ Eyes: The Future of Ground Combat and its associated podcast, Army Mad Scientist assembled six subject matter experts to discuss their experiences in modern warfare from the “bleeding edge” of battle, the future of conflict, and the requirements and challenges facing future ground warfighters. [Note: One of our panelists, Lieutenant Denys Antipov, served as a platoon leader and reconnaissance drone operator with the 81st Airborne Brigade, Ukrainian Army, fighting Russian paramilitary groups and anti-government separatists in the Donbas in 2015-2016. Sadly, Lt. Antipov was KIA on 11 May 2022 near Izium in Kharkiv, defending his homeland from the latest Russian invasion.]  Unmanned Aerial Vehicles are becoming increasingly commonplace on the battlefield for reconnaissance, direct strike, and area denial missions — these comparatively low cost systems have democratized air power, enabling lesser states and non-state actors to execute air domain operations. Information Operations will allow our adversaries to weaponize information against Soldiers and their families, our allies and partners, and local populations — such messaging could attempt to persuade Soldiers of their battlefield failures, contradict orders they are given, or convince domestic populations of their force’s imminent defeat. Adaptable, innovative leadership will be critical in a rapidly changing Operational Environment — Leaders will need to quickly adopt and integrate technological advancements with their Soldiers and be open to constant force reorganization to maintain dominance on the battlefield. Problem solving, understanding technological capabilities, and the initiative to fill leadership positions attrited through combat are key skillsets for Soldiers on the future battlefield.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles are becoming increasingly commonplace on the battlefield for reconnaissance, direct strike, and area denial missions — these comparatively low cost systems have democratized air power, enabling lesser states and non-state actors to execute air domain operations. Information Operations will allow our adversaries to weaponize information against Soldiers and their families, our allies and partners, and local populations — such messaging could attempt to persuade Soldiers of their battlefield failures, contradict orders they are given, or convince domestic populations of their force’s imminent defeat. Adaptable, innovative leadership will be critical in a rapidly changing Operational Environment — Leaders will need to quickly adopt and integrate technological advancements with their Soldiers and be open to constant force reorganization to maintain dominance on the battlefield. Problem solving, understanding technological capabilities, and the initiative to fill leadership positions attrited through combat are key skillsets for Soldiers on the future battlefield.

In Russia-Ukraine Conflict: Sign Post to the Future (Part 1), Kate Kilgore, TRADOC G-2 Intern, explored three sign posts for the future: the advent of a digital levée en masse, battlefield transparency, and narrative warfare; and addressed the public and private nature of war. The digital levée en masse blurs the line between decentralized digital activism and state-sponsored  hacking, with a trend of non-state involvement in the conflict information sphere by noncombatants unaffiliated with the belligerents. Technology is creating a transparent battlefield, enabling militaries to source information from individual civilians and private commercial entities, then target and strike high value targets. Russia’s domestic narrative and Ukraine’s international narrative have resulted in a dual information domain — the U.S. may have to redefine information advantage to simultaneously engage and shape the international public domain while penetrating an adversary’s stranglehold on its domestic information domain.

hacking, with a trend of non-state involvement in the conflict information sphere by noncombatants unaffiliated with the belligerents. Technology is creating a transparent battlefield, enabling militaries to source information from individual civilians and private commercial entities, then target and strike high value targets. Russia’s domestic narrative and Ukraine’s international narrative have resulted in a dual information domain — the U.S. may have to redefine information advantage to simultaneously engage and shape the international public domain while penetrating an adversary’s stranglehold on its domestic information domain.

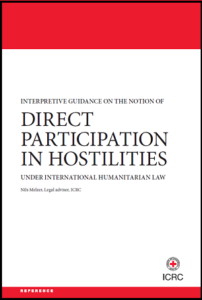

Ms. Kilgore also addressed how Democratized Intelligence is transforming the twenty-first century battlespace — making it increasingly transparent and enabling everyone to be a potential sensor and intelligence asset — while also blurring the distinction between combatant and non-combatant. This democratization of intelligence also has the potential to erode our Nation’s Information Advantage — enabling adversaries, non-state actors, and hostile individuals alike to challenge our narrative regarding future operations. Open  Source Intelligence (OSINT) and reporting have aided Ukraine’s quick response to the fast-paced modern news-cycle, enabling them to bolster international support, despite the absence of formal information sharing agreements. Ukraine’s unprecedented decision to invite private citizens from all over the globe to take part in the fight against Russia has tied its intelligence architecture to the public — individuals’ capacity to informally volunteer their services to influence the conflict signal future conflicts where such civilian capabilities could complicate Service members’ ability to distinguish between combatants and non-combatants. While Ukraine’s open dialogue with the global commons demonstrates crowdsourcing opportunities for intelligence gathering and promoting favorable narratives in a future conflict, it conversely illustrates that the Army may not be able to limit or control non-military actors’ extensive documentation of future battlefield operations. Deciding whether to operationalize greater amounts of privately collected and shared information also begs the legal question of whether using such information transforms sources into direct participants in the conflict, potentially making them combatants. In future conflicts, a U.S. Soldier’s every move could potentially be documented in theater – accurately or not – and posted online, then used nefariously by an adversary to gain information advantage and erode both domestic and international trust in our operational narrative.

Source Intelligence (OSINT) and reporting have aided Ukraine’s quick response to the fast-paced modern news-cycle, enabling them to bolster international support, despite the absence of formal information sharing agreements. Ukraine’s unprecedented decision to invite private citizens from all over the globe to take part in the fight against Russia has tied its intelligence architecture to the public — individuals’ capacity to informally volunteer their services to influence the conflict signal future conflicts where such civilian capabilities could complicate Service members’ ability to distinguish between combatants and non-combatants. While Ukraine’s open dialogue with the global commons demonstrates crowdsourcing opportunities for intelligence gathering and promoting favorable narratives in a future conflict, it conversely illustrates that the Army may not be able to limit or control non-military actors’ extensive documentation of future battlefield operations. Deciding whether to operationalize greater amounts of privately collected and shared information also begs the legal question of whether using such information transforms sources into direct participants in the conflict, potentially making them combatants. In future conflicts, a U.S. Soldier’s every move could potentially be documented in theater – accurately or not – and posted online, then used nefariously by an adversary to gain information advantage and erode both domestic and international trust in our operational narrative.

In War in Ukraine: The Urban Fight is Happening Now and its associated podcast, MAJ John Spencer (USA-Ret.), Chair of Urban Warfare Studies with the Madison Policy Forum, addressed the on-going war in Ukraine, urban warfare strategies employed by both Russian and Ukrainian military forces, and what this portends for the future of conflict. Despite Russia’s initial plans falling in line with traditional invasions, characterized by a large mass of forces that are then rapidly deployed in a “shock and awe” campaign, Ukraine’s combined arms approach to defense has prevented Russia from quickly gaining control of critical areas.  ATGMs and MANPADS have been very effective in this conflict due to Russia trading combined arms operations for speed — Russia’s rush to seize ground objectives in convoy without effectively establishing and utilizing their air superiority has led to attrition of their ground assets. The Russia-Ukraine conflict is a clear reminder that many of the lessons we’ve learned in the past — using combined arms in urban warfare, the dangers of emitting large EW signatures, and the importance of Command and Control — are all still relevant on the battlefield today. Information from around the world is being received in the combat zone and directly influencing on-going kinetic operations, demonstrating that the information age is changing the character of war. Ukraine is capable of winning in urban warfare because they do not have to actually defeat the enemy’s military power, they must only hold out long enough for the political situation to change in their favor; in this situation, not losing is winning.

ATGMs and MANPADS have been very effective in this conflict due to Russia trading combined arms operations for speed — Russia’s rush to seize ground objectives in convoy without effectively establishing and utilizing their air superiority has led to attrition of their ground assets. The Russia-Ukraine conflict is a clear reminder that many of the lessons we’ve learned in the past — using combined arms in urban warfare, the dangers of emitting large EW signatures, and the importance of Command and Control — are all still relevant on the battlefield today. Information from around the world is being received in the combat zone and directly influencing on-going kinetic operations, demonstrating that the information age is changing the character of war. Ukraine is capable of winning in urban warfare because they do not have to actually defeat the enemy’s military power, they must only hold out long enough for the political situation to change in their favor; in this situation, not losing is winning.

In Ukraine: All Roads Lead to Urban and its associated podcast, MAJ Spencer returned to explore what we’ve learned about Large Scale Combat Operations and urban conflict over the last four-plus months. Modern technology forces our societies, and those of our adversaries, to be more connected to the battlefield — enabling actors outside of the conflict zone  to leverage OSINT and possibly influence the conflict. The Battle for Kyiv demonstrated that terrain still matters — Ukrainians flooded rivers and destroyed bridges to canalize Russian invaders into chokepoints and kill zones, demonstrating a superior indigenous understanding of their environment. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine demonstrates the importance of civilians in urban conflict, as volunteers collaborated to establish defenses in depth, targeting and ambushing attackers. The Army is not learning the lessons of modern war — future conflict will happen in urban areas; the Army still doesn’t have a major school for urban warfare nor a unit focused on fighting in the urban environment — we now have the 11th Arctic Division — where is our Urban Division?

to leverage OSINT and possibly influence the conflict. The Battle for Kyiv demonstrated that terrain still matters — Ukrainians flooded rivers and destroyed bridges to canalize Russian invaders into chokepoints and kill zones, demonstrating a superior indigenous understanding of their environment. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine demonstrates the importance of civilians in urban conflict, as volunteers collaborated to establish defenses in depth, targeting and ambushing attackers. The Army is not learning the lessons of modern war — future conflict will happen in urban areas; the Army still doesn’t have a major school for urban warfare nor a unit focused on fighting in the urban environment — we now have the 11th Arctic Division — where is our Urban Division?

In The Pivotal Role of Small and Middle Powers in Conflict: Poland and the War in Ukraine , Collin Meisel and Tim Sweijs addressed the strategic importance small and middle powers play in competition, crisis, and conflict. From Poland’s pivotal role in the continuing conflict in Ukraine, Messrs. Meisel and Sweijs extrapolated the roles similarly-sized powers could play in the China-US competition in Southeast Asia. In the event of heightened competition and even the lead-up to conflict with China, small and middle  powers have the ability to implement potent deterrence by denial strategies. These powers can transform difficult-to-defend, island territories into “poison frogs” — where the military, diplomatic, and economic cost of taking and holding such territory is high. Alternatively, small powers can also be spoilers for international stability for a variety of reasons, transforming into “poisonous friends” — their geographic position and inability to fend for themselves can make them a stepping stone in great powers’ expansionist strategies. Great powers may consider them indispensable, fearing their loss will lead to regional cascading domino-effects; and their reckless behavior could drag great power partners and allies into a wider conflict. Small and middle powers’ influence capacity plays an important stabilizing role, both globally and regionally.

powers have the ability to implement potent deterrence by denial strategies. These powers can transform difficult-to-defend, island territories into “poison frogs” — where the military, diplomatic, and economic cost of taking and holding such territory is high. Alternatively, small powers can also be spoilers for international stability for a variety of reasons, transforming into “poisonous friends” — their geographic position and inability to fend for themselves can make them a stepping stone in great powers’ expansionist strategies. Great powers may consider them indispensable, fearing their loss will lead to regional cascading domino-effects; and their reckless behavior could drag great power partners and allies into a wider conflict. Small and middle powers’ influence capacity plays an important stabilizing role, both globally and regionally.

In How will the RUS-UKR Conflict Impact Russia’s Military Modernization? Dr. Jacob Barton, Director, Future Operational Environment (FOE), Army Futures Command, explores how this conflict could affect Russian military modernization, given its extensive munitions expenditures and combat losses, the international trade sanctions that have been implemented, and the resultant economic constraints. Russia will need to make radical adjustments to training, recruiting, and retention to recover from the troop losses sustained over the past four plus months — Russia is  already experiencing challenges in its recruiting efforts and will almost certainly see lower numbers of enlistments in the coming years. Based on historical weapon system production rates and current Western sanctions, the Russian defense industry will probably not be able to replace its combat losses in the next five years. If Russia replaces its destroyed equipment with its vast inventory of legacy equipment, the sustainment costs associated with these systems will adversely affect resources available for modernization. Russia has expended a tremendous amount of ammunition and ordnance; supply chain disruptions from the resulting sanctions will further hinder its ability to acquire external sources of ammunition and discreet supplies like microchips needed for its precision missiles and artillery — specifically, those Russia wants available for any potential conflict with NATO. Russia will be faced with calls for dialing back its foreign policy goals, a smaller military structure, and reduced deployed footprints, with more prominent use of private military contractors and proxies and a greater reliance on its nuclear deterrents.

already experiencing challenges in its recruiting efforts and will almost certainly see lower numbers of enlistments in the coming years. Based on historical weapon system production rates and current Western sanctions, the Russian defense industry will probably not be able to replace its combat losses in the next five years. If Russia replaces its destroyed equipment with its vast inventory of legacy equipment, the sustainment costs associated with these systems will adversely affect resources available for modernization. Russia has expended a tremendous amount of ammunition and ordnance; supply chain disruptions from the resulting sanctions will further hinder its ability to acquire external sources of ammunition and discreet supplies like microchips needed for its precision missiles and artillery — specifically, those Russia wants available for any potential conflict with NATO. Russia will be faced with calls for dialing back its foreign policy goals, a smaller military structure, and reduced deployed footprints, with more prominent use of private military contractors and proxies and a greater reliance on its nuclear deterrents.

Well before the current conflict and the associated international sanctions were emplaced, Ray Finch, Eurasian Analyst, Foreign Military Studies Office, TRADOC G-2, addressed the inherent challenges facing innovation in an autocratic society and why it’s doubtful that Russia’s military innovation center — Era Military Innovation Technopark, near the city of Anapa (Krasnodar Region) on the northern coast of the Black Sea — will ever usher in a new era of Russian military innovation. While Russian scientists have often been at the forefront of technological innovations, the country’s poor legal system prevents these discoveries from ever bearing fruit. Stifling bureaucracy and a broken legal system prevent Russian scientists and innovators from profiting from their discoveries. Additionally, many smart,  young Russians believe that their country is headed in the wrong direction and are looking for opportunities elsewhere — young and talented Russians are “voting with their feet” and pursuing careers abroad. While it is famous for its tanks, artillery, and rocket systems, Russia has struggled to create anything which might be qualified as a technological marvel in the civilian sector. As some Russian observers have put it, “no matter what the state tries to develop, it ends up being a Kalashnikov.” Despite the façade of a uniformed, law-governed state, Russia continues to rank near the bottom on the global corruption index. Private Russian companies will likely think twice before deciding to invest in the Era Technopark, unless of course, the Kremlin makes them an offer they cannot refuse. Moreover, Era scientists may not be fully committed, understanding that the “milk” of their technological discoveries will likely by expropriated by their uniformed bosses.

young Russians believe that their country is headed in the wrong direction and are looking for opportunities elsewhere — young and talented Russians are “voting with their feet” and pursuing careers abroad. While it is famous for its tanks, artillery, and rocket systems, Russia has struggled to create anything which might be qualified as a technological marvel in the civilian sector. As some Russian observers have put it, “no matter what the state tries to develop, it ends up being a Kalashnikov.” Despite the façade of a uniformed, law-governed state, Russia continues to rank near the bottom on the global corruption index. Private Russian companies will likely think twice before deciding to invest in the Era Technopark, unless of course, the Kremlin makes them an offer they cannot refuse. Moreover, Era scientists may not be fully committed, understanding that the “milk” of their technological discoveries will likely by expropriated by their uniformed bosses.

If you enjoyed this post, check out the following additional related content:

The Operational Environment (2021-2030): Great Power Competition, Crisis, and Conflict, its comprehensive source document, and the Threats to 2030 video

Russia Landing Zone content on the TRADOC G-2‘s Operational Environment Enterprise public facing page — including the BiteSize Russia weekly topics

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

Modern technology forces our societies, and those of our adversaries, to be more connected to the battlefield. As the Ukrainian “Tik-Tok” war demonstrates, such connectedness can allow

Modern technology forces our societies, and those of our adversaries, to be more connected to the battlefield. As the Ukrainian “Tik-Tok” war demonstrates, such connectedness can allow

Today, Soldiers and their families are

Today, Soldiers and their families are

The reduced cost and increased sophistication and access to private technology is facilitating a democratization of intelligence gathering and dissemination capabilities, empowering smaller nations and non-state actors, and ushering in an Operational Environment where battlefields are transparent to all. This exponentially increases the amount of data and information available and the number of entities to whom it is available. Russia’s on-going “special military operation” in Ukraine serves as a proving ground — testing the limits of this emergent, democratized PED capability and showcasing non-government entities’ growing ability to impact conflicts around the globe. Ukraine’s willingness to integrate democratically-sourced information, data, and analysis provides a blueprint, allowing nations and non-state actors alike to develop and maintain a capable intelligence enterprise, and possibly increasing the ability of states without formal intelligence sharing agreements to collaborate more effectively. The impact of democratized intelligence on the Operational Environment presents important operational and legal questions for consideration as the U.S. Army continues to successfully compete, deter aggression, and failing that, fight and decisively win future conflicts.

The reduced cost and increased sophistication and access to private technology is facilitating a democratization of intelligence gathering and dissemination capabilities, empowering smaller nations and non-state actors, and ushering in an Operational Environment where battlefields are transparent to all. This exponentially increases the amount of data and information available and the number of entities to whom it is available. Russia’s on-going “special military operation” in Ukraine serves as a proving ground — testing the limits of this emergent, democratized PED capability and showcasing non-government entities’ growing ability to impact conflicts around the globe. Ukraine’s willingness to integrate democratically-sourced information, data, and analysis provides a blueprint, allowing nations and non-state actors alike to develop and maintain a capable intelligence enterprise, and possibly increasing the ability of states without formal intelligence sharing agreements to collaborate more effectively. The impact of democratized intelligence on the Operational Environment presents important operational and legal questions for consideration as the U.S. Army continues to successfully compete, deter aggression, and failing that, fight and decisively win future conflicts.

the fast-paced modern news-cycle, which has bolstered international support regardless of many nations’ lack of formal information sharing agreements with Ukraine.

the fast-paced modern news-cycle, which has bolstered international support regardless of many nations’ lack of formal information sharing agreements with Ukraine. example of the larger Facebook-coordinated effort of Ukrainians with private drones submitting Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) information to the defense effort. Ukrainian app developers and programmers have created ad hoc digital infrastructures that allow civilians to document

example of the larger Facebook-coordinated effort of Ukrainians with private drones submitting Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) information to the defense effort. Ukrainian app developers and programmers have created ad hoc digital infrastructures that allow civilians to document “hactivists” can target and disrupt a nation’s vital

“hactivists” can target and disrupt a nation’s vital  According to the

According to the  potentially be documented in theater – accurately or not – and posted by bystanders, which could then be nefariously used by an adversary to gain

potentially be documented in theater – accurately or not – and posted by bystanders, which could then be nefariously used by an adversary to gain

While

While  Raft provides an innovation space for people who are similarly mission-focused, tackling vexing challenges with passion and enthusiasm. Ms. Mishra seeks to inspire other women in and out of the GovTech space and excite them enough to join the movement of providing better solutions and services to the defense industry through sustainable, emerging technology.

Raft provides an innovation space for people who are similarly mission-focused, tackling vexing challenges with passion and enthusiasm. Ms. Mishra seeks to inspire other women in and out of the GovTech space and excite them enough to join the movement of providing better solutions and services to the defense industry through sustainable, emerging technology.

The amount of Russian Armed Forces casualties from the conflict is staggering. According to independent estimates from last month, approximately 15,000 Russian troops have been killed in the war. Considering the investment required to produce these soldiers, Russia cannot afford to lose the volume of soldiers its leaders appear willing to sacrifice. Consider that an infantry lieutenant costs Russia $10,000 to train over five years, with other officers costing up to $60,000 each. An experienced fighter pilot can cost up to $14 million to train over a period of 14 years.

The amount of Russian Armed Forces casualties from the conflict is staggering. According to independent estimates from last month, approximately 15,000 Russian troops have been killed in the war. Considering the investment required to produce these soldiers, Russia cannot afford to lose the volume of soldiers its leaders appear willing to sacrifice. Consider that an infantry lieutenant costs Russia $10,000 to train over five years, with other officers costing up to $60,000 each. An experienced fighter pilot can cost up to $14 million to train over a period of 14 years.

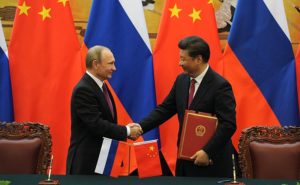

also on increasingly subservient to its southern neighbor. Most signs suggest that Russia’s leaders would be unwilling to accept a role that makes Russia a “junior partner” to China.

also on increasingly subservient to its southern neighbor. Most signs suggest that Russia’s leaders would be unwilling to accept a role that makes Russia a “junior partner” to China. Ministry sees its GDP contracting by 12.4%, while Western economists say the drop could be over 15 percent. Meanwhile, Russia’s official military spending in 2021 increased by 2.9% to $65.9 billion, or just over 4% of Russia’s GDP, according to SIPRI.

Ministry sees its GDP contracting by 12.4%, while Western economists say the drop could be over 15 percent. Meanwhile, Russia’s official military spending in 2021 increased by 2.9% to $65.9 billion, or just over 4% of Russia’s GDP, according to SIPRI. According to Congressional Research Service reports, Aerospace Forces and the Russian Navy received top priority during GPV 2020, allowing for the introduction of new and upgraded legacy systems, including improved missiles and precision-guided munitions.

According to Congressional Research Service reports, Aerospace Forces and the Russian Navy received top priority during GPV 2020, allowing for the introduction of new and upgraded legacy systems, including improved missiles and precision-guided munitions.