[Editor’s Note: The Army’s Mad Scientist Laboratory is pleased to feature today’s post by the United States Army War College (USAWC) student team “Forecastica” — excerpted from their final report: China 2049: The Flight of a Particle Board Dragon. This report documents the findings from their group Strategic Research Requirement that occurred over eight months (October 2021 to May 2022). The Forecastica Team consisted of COL Paul M. Bonano (USA), COL Johannes E. Castro (USA), COL Eric P. Magistad (USA),  Lt. Col. Stacy N. Slate (USAF), and LTC Andrew J. Wiker (USA). Their requirement synthesized and analyzed open-source documents to answer the following question: How can China meet its national objectives to become the world’s dominant power by 2049? Read on to learn what our most recently proclaimed Mad Scientists say about how our pacing threat is building regional hegemony!]

Lt. Col. Stacy N. Slate (USAF), and LTC Andrew J. Wiker (USA). Their requirement synthesized and analyzed open-source documents to answer the following question: How can China meet its national objectives to become the world’s dominant power by 2049? Read on to learn what our most recently proclaimed Mad Scientists say about how our pacing threat is building regional hegemony!]

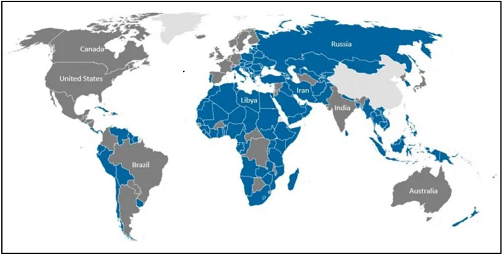

China will likely* focus on three areas to establish itself as the regional hegemon. By increasing its regional influence to promote stability and self-interest, the country can extend its reach and economic influence across the region. The PRC is likely to continue using the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to establish regional dependencies. The global network of railroads, ports, highways, and infrastructure projects Beijing develops and funds primarily through loans to other nations expands its economic and geopolitical influence over regional countries through debt and trade, while providing access to export markets and resources. Most Asian countries participate in the BRI (Figure 1).

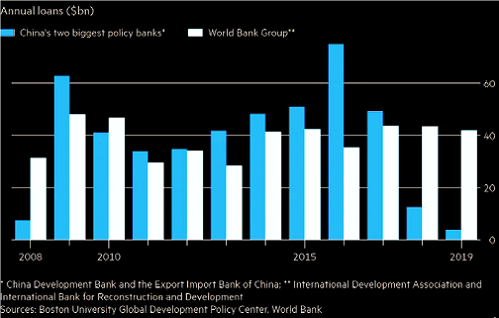

However, China faces three obstacles to becoming the regional hegemon. First, continued BRI expansion and overseas investments will strain China’s corporate debt and public debt levels. The Atlantic Council estimates the potential slowdown from deleveraging overseas lending and real estate debt reduction could cut its GDP growth by one percentage point per year until 2025. The number of loans from the PRC’s two biggest policy banks has already fallen drastically from their 2016 highs (Figure 2). Reductions in regional investment are likely to limit China’s ability to increase dependencies within the region.

Second, while Chinese firms excel at “adaptive innovation” based on theft or forced technology transfer, they lack many advantages of an open economic system maximizing competition. Innovation is a product of flexible financing and trust in government institutions, and the PRC lacks these structural advantages for the foreseeable future. The CCP’s centralized decision-making helps drive whole-of-government resource mobilization, but centrally driven models ultimately inhibit true innovation. Over the long term, the PRC’s manufacturing productivity and economic health are questionable, but its regional dominance may go unchallenged.

Finally, following China’s border dispute with India in 2020, China built alliances through the BRI, effectively surrounding India with ports capable of supporting the PLA-Navy. This move pushed India into strengthened relations with their Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) partners (Figure 3) and increased naval partnerships throughout the Indo-Pacific to counter Sino influence. The QUAD will likely continue to hinder Chinese regional dominance unless they amend their relationship with India.

Despite the likely reduction in its regional investments, China is likely to achieve a significant degree of regional influence based on the regional dependencies it has already established.

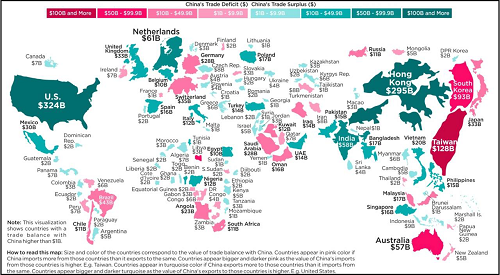

To reduce the Western influence in the region, China is likely to position itself as the regional economic and security partner of choice. Economically, Beijing is highly likely to use BRI-like infrastructure development initiatives to foster economic dependencies and develop influence in neighboring countries through trade agreements. Its trade with Asian countries accounts for half of China’s exports, while key U.S. Allies (e.g., Australia, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan) have trade surpluses (Figure 4). Decisions on who can access its growing domestic market will shape regional trade.

If Beijing maintains its regional export and economic power, its partnership opportunities will likely increase. Chinese financial and export strength provides natural conduits to the rest of the region through signed agreements like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and an agreement between ASEAN and China to officially upgrade their ties to a comprehensive strategic partnership. The economic dependencies are likely to complicate international consensus on economic sanctions directed towards China.

China is also likely to increase participation in UN peacekeeping missions and disaster relief and participate in combined training exercises throughout the South China Sea to demonstrate its reliability as a security partner. Foreign Military Sales, including with U.S. partners such as Thailand, increase opportunities for the PLA to engage with regional militaries and strengthen relationships.

Finally, Xi Jinping is highly likely to continue building alliances in the Indian Ocean through the BRI. Dual civil/military port projects in Pakistan, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka allow the PLA-Navy to isolate its regional geopolitical competitor, India, militarily. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor project, connecting western China directly to the Indian Ocean shipping lanes through Pakistan’s Gwadar Port with pipelines, railroads, and roads, is likely economically unviable.

Finally, Xi Jinping is highly likely to continue building alliances in the Indian Ocean through the BRI. Dual civil/military port projects in Pakistan, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka allow the PLA-Navy to isolate its regional geopolitical competitor, India, militarily. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor project, connecting western China directly to the Indian Ocean shipping lanes through Pakistan’s Gwadar Port with pipelines, railroads, and roads, is likely economically unviable.  Still, the geopolitical benefit outweighs the cost if the isolation forces India to reach an accommodation with China and downgrade its relationship with the US.

Still, the geopolitical benefit outweighs the cost if the isolation forces India to reach an accommodation with China and downgrade its relationship with the US.

Beijing faces challenges in becoming the economic and security partner of choice. As discussed earlier, the continued expansion of the BRI strains China’s corporate debt and public debt levels, likely threatening financing for future infrastructure development projects. Its claims to disputed islands in their near seas and continued aggression toward Taiwan continue to cause friction, increase tension, and erode trust. The disputes are certain to push their SE Asian neighbors further toward security cooperation with the US, regardless of their economic ties.

Overall, China’s chances are a little less likely to earn the required trust from its neighbors and drive the US out of the region, primarily due to the tension between their regional neighbors’ economic ties to China, but also due to security relationships with the US.

China must build an effective PLA and A2AD capability (Figure 5) to develop a credible threat of hard power and deter intervention. Modernization through the development of precision-guided munitions, hypersonic glide vehicles, UAVs, cyber-warfare, and intelligentization enabling complex thinking and decision-making will likely provide an A2AD advantage. To this end, the PRC has invested billions of dollars in military modernization and reorganized the PLA into joint commands while increasing joint exercises with Russia and Iran. The modernization mainly focuses on deterring Western military interventions in the region.

The PLA faces significant modernization challenges due to its deep-seated culture of over-centralization of command authority, top-down control of military assets, and failure to incorporate the style of decentralized mission command demanded by technology-driven future warfare. They currently lack a plan to prioritize incorporating new technologies into their training strategy to challenge their soldiers to fight and win in a complex multi-domain environment.

Still, China is likely to achieve this goal due to its ambitions to reach parity with the West and its ability to radiate sharp power regionally.

If you enjoyed this post, check out the comprehensive report — China 2049: The Flight of a Particle Board Dragon — from which it was excerpted…

… as well as the following related TRADOC G-2 and Mad Scientist content:

China Landing Zone content on the TRADOC G-2‘s Operational Environment Enterprise public facing page — including the BiteSize China weekly topics, ATP 7-100.3, Chinese Tactics, People’s Liberation Army Ground Forces Quick Reference Guide, and more!

The Operational Environment (2021-2030): Great Power Competition, Crisis, and Conflict, along with its source document

How China Fights and associated podcast

The Most Consequential Adversaries and associated podcast, with

China’s PLA Modernization through the DOTMLPF-P Lens, by Dr. Jacob Barton

“Intelligentization” and a Chinese Vision of Future War

Competition and Conflict in the Next Decade

Disrupting the “Chinese Dream” – Eight Insights on how to win the Competition with China

Competition in 2035: Anticipating Chinese Exploitation of Operational Environments

Disinformation, Revisionism, and China with Doowan Lee and associated podcast

China and Russia: Achieving Decision Dominance and Information Advantage, by Ian Sullivan

The PLA and UAVs – Automating the Battlefield and Enhancing Training

A Chinese Perspective on Future Urban Unmanned Operations

China: “New Concepts” in Unmanned Combat and Cyber and Electronic Warfare

The PLA: Close Combat in the Information Age and the “Blade of Victory”

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

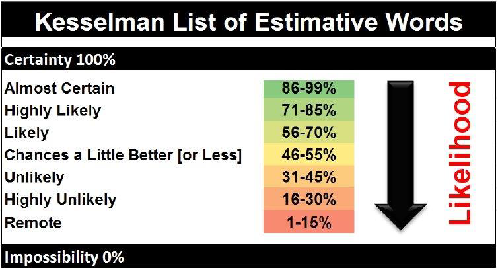

* Forcastica’s analysts used Kesselman’s List of Estimative Words (below) to express estimative probability in deciding the likelihood of China’s success across a spectrum of actions they determined necessary to become the world’s dominant power by 2049.

Dr. Mica Hall

Dr. Mica Hall

Regular readers will recall our

Regular readers will recall our  Unmanned Aerial Vehicles are becoming increasingly commonplace on the battlefield for reconnaissance, direct strike, and area denial missions — these comparatively low cost systems have democratized air power, enabling lesser states and non-state actors to execute air domain operations. Information Operations will allow our adversaries to weaponize information against Soldiers and their families, our allies and partners, and local populations — such messaging could attempt to persuade Soldiers of their battlefield failures, contradict orders they are given, or convince domestic populations of their force’s imminent defeat. Adaptable, innovative leadership will be critical in a rapidly changing Operational Environment — Leaders will need to quickly adopt and integrate technological advancements with their Soldiers and be open to constant force reorganization to maintain dominance on the battlefield. Problem solving, understanding technological capabilities, and the initiative to fill leadership positions attrited through combat are key skillsets for Soldiers on the future battlefield.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles are becoming increasingly commonplace on the battlefield for reconnaissance, direct strike, and area denial missions — these comparatively low cost systems have democratized air power, enabling lesser states and non-state actors to execute air domain operations. Information Operations will allow our adversaries to weaponize information against Soldiers and their families, our allies and partners, and local populations — such messaging could attempt to persuade Soldiers of their battlefield failures, contradict orders they are given, or convince domestic populations of their force’s imminent defeat. Adaptable, innovative leadership will be critical in a rapidly changing Operational Environment — Leaders will need to quickly adopt and integrate technological advancements with their Soldiers and be open to constant force reorganization to maintain dominance on the battlefield. Problem solving, understanding technological capabilities, and the initiative to fill leadership positions attrited through combat are key skillsets for Soldiers on the future battlefield.  hacking, with a trend of non-state involvement in the conflict information sphere by noncombatants unaffiliated with the belligerents. Technology is creating a transparent battlefield, enabling militaries to source information from individual civilians and private commercial entities, then target and strike high value targets. Russia’s domestic narrative and Ukraine’s international narrative have resulted in a dual information domain — the U.S. may have to redefine

hacking, with a trend of non-state involvement in the conflict information sphere by noncombatants unaffiliated with the belligerents. Technology is creating a transparent battlefield, enabling militaries to source information from individual civilians and private commercial entities, then target and strike high value targets. Russia’s domestic narrative and Ukraine’s international narrative have resulted in a dual information domain — the U.S. may have to redefine  Source Intelligence (OSINT) and reporting have aided Ukraine’s quick response to the fast-paced modern news-cycle, enabling them to bolster international support, despite the absence of formal information sharing agreements. Ukraine’s unprecedented decision to invite private citizens from all over the globe to take part in the fight against Russia has tied its intelligence architecture to the public — individuals’ capacity to informally volunteer their services to influence the conflict signal future conflicts where such civilian capabilities could complicate Service members’ ability to distinguish between combatants and non-combatants. While Ukraine’s open dialogue with the global commons demonstrates crowdsourcing opportunities for intelligence gathering and promoting favorable narratives in a future conflict, it conversely illustrates that the Army may not be able to limit or control non-military actors’ extensive documentation of future battlefield operations. Deciding whether to operationalize greater amounts of privately collected and shared information also begs the legal question of whether using such information transforms sources into direct participants in the conflict, potentially making them combatants. In future conflicts, a U.S. Soldier’s every move could potentially be documented in theater – accurately or not – and posted online, then used nefariously by an adversary to gain information advantage and erode both domestic and international trust in our operational narrative.

Source Intelligence (OSINT) and reporting have aided Ukraine’s quick response to the fast-paced modern news-cycle, enabling them to bolster international support, despite the absence of formal information sharing agreements. Ukraine’s unprecedented decision to invite private citizens from all over the globe to take part in the fight against Russia has tied its intelligence architecture to the public — individuals’ capacity to informally volunteer their services to influence the conflict signal future conflicts where such civilian capabilities could complicate Service members’ ability to distinguish between combatants and non-combatants. While Ukraine’s open dialogue with the global commons demonstrates crowdsourcing opportunities for intelligence gathering and promoting favorable narratives in a future conflict, it conversely illustrates that the Army may not be able to limit or control non-military actors’ extensive documentation of future battlefield operations. Deciding whether to operationalize greater amounts of privately collected and shared information also begs the legal question of whether using such information transforms sources into direct participants in the conflict, potentially making them combatants. In future conflicts, a U.S. Soldier’s every move could potentially be documented in theater – accurately or not – and posted online, then used nefariously by an adversary to gain information advantage and erode both domestic and international trust in our operational narrative. ATGMs and MANPADS have been very effective in this conflict due to Russia trading combined arms operations for speed — Russia’s rush to seize ground objectives in convoy without effectively establishing and utilizing their air superiority has led to attrition of their ground assets. The Russia-Ukraine conflict is a clear reminder that many of the lessons we’ve learned in the past — using combined arms in urban warfare, the dangers of emitting large EW signatures, and the importance of Command and Control — are all still relevant on the battlefield today. Information from around the world is being received in the combat zone and directly influencing on-going kinetic operations, demonstrating that the information age is changing the character of war. Ukraine is capable of winning in urban warfare because they do not have to actually defeat the enemy’s military power, they must only hold out long enough for the political situation to change in their favor; in this situation, not losing is winning.

ATGMs and MANPADS have been very effective in this conflict due to Russia trading combined arms operations for speed — Russia’s rush to seize ground objectives in convoy without effectively establishing and utilizing their air superiority has led to attrition of their ground assets. The Russia-Ukraine conflict is a clear reminder that many of the lessons we’ve learned in the past — using combined arms in urban warfare, the dangers of emitting large EW signatures, and the importance of Command and Control — are all still relevant on the battlefield today. Information from around the world is being received in the combat zone and directly influencing on-going kinetic operations, demonstrating that the information age is changing the character of war. Ukraine is capable of winning in urban warfare because they do not have to actually defeat the enemy’s military power, they must only hold out long enough for the political situation to change in their favor; in this situation, not losing is winning. to leverage OSINT and possibly influence the conflict. The Battle for Kyiv demonstrated that terrain still matters — Ukrainians flooded rivers and destroyed bridges to canalize Russian invaders into chokepoints and kill zones, demonstrating a superior indigenous understanding of their environment. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine demonstrates the importance of civilians in urban conflict, as volunteers collaborated to establish defenses in depth, targeting and ambushing attackers. The Army is not learning the lessons of modern war — future conflict will happen in urban areas; the Army still doesn’t have a major school for urban warfare nor a unit focused on fighting in the urban environment — we now have the 11th Arctic Division — where is our Urban Division?

to leverage OSINT and possibly influence the conflict. The Battle for Kyiv demonstrated that terrain still matters — Ukrainians flooded rivers and destroyed bridges to canalize Russian invaders into chokepoints and kill zones, demonstrating a superior indigenous understanding of their environment. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine demonstrates the importance of civilians in urban conflict, as volunteers collaborated to establish defenses in depth, targeting and ambushing attackers. The Army is not learning the lessons of modern war — future conflict will happen in urban areas; the Army still doesn’t have a major school for urban warfare nor a unit focused on fighting in the urban environment — we now have the 11th Arctic Division — where is our Urban Division? powers have the ability to implement potent deterrence by denial strategies. These powers can transform difficult-to-defend, island territories into “poison frogs” — where the military, diplomatic, and economic cost of taking and holding such territory is high. Alternatively, small powers can also be spoilers for international stability for a variety of reasons, transforming into “poisonous friends” — their geographic position and inability to fend for themselves can make them a stepping stone in great powers’ expansionist strategies. Great powers may consider them indispensable, fearing their loss will lead to regional cascading domino-effects; and their reckless behavior could drag great power partners and allies into a wider conflict. Small and middle powers’

powers have the ability to implement potent deterrence by denial strategies. These powers can transform difficult-to-defend, island territories into “poison frogs” — where the military, diplomatic, and economic cost of taking and holding such territory is high. Alternatively, small powers can also be spoilers for international stability for a variety of reasons, transforming into “poisonous friends” — their geographic position and inability to fend for themselves can make them a stepping stone in great powers’ expansionist strategies. Great powers may consider them indispensable, fearing their loss will lead to regional cascading domino-effects; and their reckless behavior could drag great power partners and allies into a wider conflict. Small and middle powers’  already experiencing challenges in its recruiting efforts and will almost certainly see lower numbers of enlistments in the coming years. Based on historical weapon system production rates and current Western sanctions, the Russian defense industry will probably not be able to replace its combat losses in the next five years. If Russia replaces its destroyed equipment with its vast inventory of legacy equipment, the sustainment costs associated with these systems will adversely affect resources available for modernization. Russia has expended a tremendous amount of ammunition and ordnance; supply chain disruptions from the resulting sanctions will further hinder its ability to acquire external sources of ammunition and discreet supplies like microchips needed for its precision missiles and artillery — specifically, those Russia wants available for any potential conflict with NATO. Russia will be faced with calls for dialing back its foreign policy goals, a smaller military structure, and reduced deployed footprints, with more prominent use of private military contractors and proxies and a greater reliance on its nuclear deterrents.

already experiencing challenges in its recruiting efforts and will almost certainly see lower numbers of enlistments in the coming years. Based on historical weapon system production rates and current Western sanctions, the Russian defense industry will probably not be able to replace its combat losses in the next five years. If Russia replaces its destroyed equipment with its vast inventory of legacy equipment, the sustainment costs associated with these systems will adversely affect resources available for modernization. Russia has expended a tremendous amount of ammunition and ordnance; supply chain disruptions from the resulting sanctions will further hinder its ability to acquire external sources of ammunition and discreet supplies like microchips needed for its precision missiles and artillery — specifically, those Russia wants available for any potential conflict with NATO. Russia will be faced with calls for dialing back its foreign policy goals, a smaller military structure, and reduced deployed footprints, with more prominent use of private military contractors and proxies and a greater reliance on its nuclear deterrents. young Russians believe that their country is headed in the wrong direction and are looking for opportunities elsewhere — young and talented Russians are “voting with their feet” and pursuing careers abroad. While it is famous for its tanks, artillery, and rocket systems, Russia has struggled to create anything which might be qualified as a technological marvel in the civilian sector. As some Russian observers have put it, “no matter what the state tries to develop, it ends up being a Kalashnikov.” Despite the façade of a uniformed, law-governed state, Russia continues to rank near the bottom on the global corruption index. Private Russian companies will likely think twice before deciding to invest in the Era Technopark, unless of course, the Kremlin makes them an offer they cannot refuse. Moreover, Era scientists may not be fully committed, understanding that the “milk” of their technological discoveries will likely by expropriated by their uniformed bosses.

young Russians believe that their country is headed in the wrong direction and are looking for opportunities elsewhere — young and talented Russians are “voting with their feet” and pursuing careers abroad. While it is famous for its tanks, artillery, and rocket systems, Russia has struggled to create anything which might be qualified as a technological marvel in the civilian sector. As some Russian observers have put it, “no matter what the state tries to develop, it ends up being a Kalashnikov.” Despite the façade of a uniformed, law-governed state, Russia continues to rank near the bottom on the global corruption index. Private Russian companies will likely think twice before deciding to invest in the Era Technopark, unless of course, the Kremlin makes them an offer they cannot refuse. Moreover, Era scientists may not be fully committed, understanding that the “milk” of their technological discoveries will likely by expropriated by their uniformed bosses.

Modern technology forces our societies, and those of our adversaries, to be more connected to the battlefield. As the Ukrainian “Tik-Tok” war demonstrates, such connectedness can allow

Modern technology forces our societies, and those of our adversaries, to be more connected to the battlefield. As the Ukrainian “Tik-Tok” war demonstrates, such connectedness can allow

Today, Soldiers and their families are

Today, Soldiers and their families are