[Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist Laboratory welcomes returning guest blogger and proclaimed Mad Scientist Mr. Howard R. Simkin with his submission to our Mad Scientist Crowdsourcing topic from earlier this summer on The Operational Environment: What Will Change and What Will Drive It – Today to 2035? Mr. Simkin’s post addresses the military challenges posed by Splinternets. Competition during Multi-Domain Operations is predicated on our Forces’ capability to conduct cyber and influence operations against and inside our strategic competitors’ networks. In a world of splinternets, our flexibility to conduct and respond to non-kinetic engagements is challenged by this new reality in the operational environment. (Note: Some of the embedded links in this post are best accessed using non-DoD networks.)]

Purpose.

Purpose.

This paper discusses the splintering of the Internet that is currently underway – the creation of what are commonly being called splinternets. Most versions of the future operational environment assume an Internet that is largely accessible to all. Recent trends point to a splintering effect as various nation states or multi-state entities seek to regulate access to or isolate their portion of the Internet.1, 2 This paper will briefly discuss the impacts of those tendencies and propose an operational response.

The Problem.

The Problem.

What are the impacts of a future operational environment in which the Internet has fractured into a number of mutually exclusive subsets, referred to as splinternets?

Background.

Splinternets threaten both access to data and the exponential growth of the Internet as a global commons. There are two main drivers fracturing the Internet. One is regulation and the other is isolationism. Rooted in politics, the Internet is being fractured by regulation and isolationism. Counterbalancing this fracturing is the Distributed Web (DWeb).

Regulation.

Regulation usually involves revenue or internal security. While admirable in intent, regulations cast a chill over the growth and health of the Internet.3 Even well-intentioned regulations become a burden which forces smaller operators to go out of business or to ignore the regulations. Depending on the country involved, activity which was perfectly legal can become illegal by bureaucratic fiat. This acts as a further impetus to drive users to alternative platforms. An example is the European Union (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which came into effect on 25 May 2018. It includes a number of provisions which make it far more difficult to collect data. The GDPR covers not only entities based in the EU but also those who have users in the EU.4 U.S. companies such as Facebook have scrambled to comply so as to maintain access to the EU virtual space.5

![]() Isolation.

Isolation.

China is the leader in efforts to isolate their portion of the internet from outside influence.6 To accomplish this, they have received help from their own tech giants as well as U.S. companies such as Google.7 The Chinese have made it very difficult for outside entities to penetrate the “Great Firewall” while maintaining the ability of the Peoples Liberation Army (PLA) to conduct malign activities across the Internet.8 Recently, Eric Schmidt, the former CEO of Google opined that China would succeed in splitting the Internet in the not too distant future.9

Russia has also proposed a similar strategy, which they would extend to the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa). The reason given is the “dominance of the US and a few EU states concerning Internet regulation” which Russia sees as a “serious danger” to its safety, RosBiznesKonsalting (RBK)10 quotes from minutes taken at a meeting of the Russian Security Council. Having its own root servers would make Russia independent of monitors like the International Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) and protect the country in the event of “outages or deliberate interference.” “Putin sees [the] Internet as [a] CIA tool.”11

Russia has also proposed a similar strategy, which they would extend to the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa). The reason given is the “dominance of the US and a few EU states concerning Internet regulation” which Russia sees as a “serious danger” to its safety, RosBiznesKonsalting (RBK)10 quotes from minutes taken at a meeting of the Russian Security Council. Having its own root servers would make Russia independent of monitors like the International Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) and protect the country in the event of “outages or deliberate interference.” “Putin sees [the] Internet as [a] CIA tool.”11

Distributed Web (DWeb).

Distributed Web (DWeb).

The DWeb is “a peer-to-peer Internet that is free from firewalls, government regulation, and spying.” Admittedly, the DWeb is a difficult problem. However, both the University of Michigan and a private firm, Maidsafe claim to be close to a solution.12 Brewster Kahle, founder of the Internet Archive and organizer of the first Decentralized Web Summit two years ago, recently advocated a “DWeb Camp.” Should a DWeb become a reality, many of the current efforts by governments to control or regulate the Internet would founder.

Operational Response.

Operational Response.

Our operational response should involve Special Operations Forces (SOF), Space, and Cyber forces. The creation of splinternets places a premium on the ability to gain physical access to the splinternet’s internal networks. SOF is an ideal force to perform this operation because of their ability to work in politically sensitive and denied environments with or through indigenous populations. Once SOF gains physical access, Space would be the most logical means to send and receive data. Cyber forces would then perform operations within the splinternet.

Conclusion.

Most versions of the future operational environment assume an Internet that is largely accessible to all. Therefore, splinternets are an important ‘alternative future’ to consider. In conjunction with Space and Cyber forces, SOF can play a key role in the operational response to allow the Joint Force to continue to operate against splinternet capable adversaries.

If you enjoyed this post, please see:

– Mr. Simkin‘s previous Mad Scientist Laboratory posts:

Keeping the Edge, and

… as well as his winning Call for Ideas presentation The Future ODA (Operational Detachment Alpha) 2035-2050, delivered at the Mad Scientist Bio Convergence and Soldier 2050 Conference, co-hosted with SRI International on 8–9 March 2018 at their Menlo Park campus in California.

– LtCol Jennifer “JJ” Snow‘s blog post Alternet: What Happens When the Internet is No Longer Trusted?

– Dr. Mica Hall‘s blog post The Cryptoruble as a Stepping Stone to Digital Sovereignty

Howard R. Simkin is a Senior Concept Developer in the DCS, G-9 Capability Development & Integration Directorate, U.S. Army Special Operations Command. He has over 40 years of combined military, law enforcement, defense contractor, and government experience. He is a retired Special Forces officer with a wide variety of special operations experience. He is also a proclaimed Mad Scientist.

References:

Baker, Dr. Jessica. “What Does GDPR Mean For You?” Digital Guardian. July 11, 2018. https://digitalguardian.com/blog/what-does-gdpr-mean-for-you (accessed September 14, 2018).

Hoffer, Eric. Reflections on the Human Condition. New York: Harper and Row, 1973.

L.S. “The Economist explains, “What is the splinternet”?” The Economist. November 22, 2016. https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2016/11/22/what-is-the-splinternet (accessed September 14, 2018).

Nash, Charlie. “The Google Tapes: Employees Applauded Company for Taking Bold Stance Against China.” Breitbart. September 13, 2018. https://www.breitbart.com/tech/2018/09/13/the-google-tape-employees-applauded-company-for-taking-bold-stance-against-china/ (accessed September 14, 2018).

Sanger, David E. The Perfect Weapon, War, Sabotage, and Fear in the Cyber Age. New York: Crown (Kindle Edition), 2018.

Sterling, Bruce. “The China Splinternet Model is Winning.” Wired. July 2, 2016. https://www.wired.com/beyond-the-beyond/2016/07/china-splinternet-model-winning/ (accessed September 2018, 2018).

Tangermann, Victor. “With GDPR Decision, Zuckerberg Proves Yet Again He Has Learned Absolutely Nothing From the Cambridge Analytica Scandal.” Futurism. April 4, 2018. https://futurism.com/zuckerberg-gdpr-cambridge-analytica/ (accessed September 14, 2018).

Tanguay, Pierre, Sabrina Dubé-Morneau, and Gaëlle Engelberts. “Splinternets: How Online Balkanization is Creating a Headache for Digital Content Distribution.” CMF Trends. January 31, 2018. https://trends.cmf-fmc.ca/splinternets-how-online-balkanization-is-creating-a-headache-for-digital-content-distribution/ (accessed September 2018, 2018).

End Notes:

1 Tanguay, Pierre, Sabrina Dubé-Morneau, and Gaëlle Engelberts. “Splinternets: How Online Balkanization is Creating a Headache for Digital Content Distribution.” CMF Trends. January 31, 2018. https://trends.cmf-fmc.ca/splinternets-how-online-balkanization-is-creating-a-headache-for-digital-content-distribution/ (accessed September 2018, 2018).

2 L.S. “The Economist explains, “What is the splinternet”?” The Economist. November 22, 2016. https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2016/11/22/what-is-the-splinternet (accessed September 14, 2018).

3 Duckett, Chris. “The race to ruin the internet is upon us”. ZDNet. 23 September 2018. https://www.zdnet.com/article/the-race-to-ruin-the-internet-is-upon-us/ (accessed November 13, 2018).

4 Baker, Dr. Jessica. “What Does GDPR Mean For You?” Digital Guardian. July 11, 2018. https://digitalguardian.com/blog/what-does-gdpr-mean-for-you (accessed September 14, 2018).

5 Tangermann, Victor. “With GDPR Decision, Zuckerberg Proves Yet Again He Has Learned Absolutely Nothing From the Cambridge Analytica Scandal.” Futurism. April 4, 2018. https://futurism.com/zuckerberg-gdpr-cambridge-analytica/ (accessed September 14, 2018).

6 Sterling, Bruce. “The China Splinternet Model is Winning.” Wired. July 2, 2016. https://www.wired.com/beyond-the-beyond/2016/07/china-splinternet-model-winning/ (accessed September 2018, 2018).

7 Nash, Charlie. “The Google Tapes: Employees Applauded Company for Taking Bold Stance Against China.” Breitbart. September 13, 2018. https://www.breitbart.com/tech/2018/09/13/the-google-tape-employees-applauded-company-for-taking-bold-stance-against-china/ (accessed September 14, 2018).

8 Chan, Edward. “Quick Take: The Great Firewall.” Bloomberg News. November 5, 2018. https://www.bloomberg.com/quicktake/great-firewall-of-china (accessed November 13, 2018).

9 Kolodny, Lora. “Former Google CEO predicts the internet will split in two — and one part will be led by China.” CNBC. September 20, 2018. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/09/20/eric-schmidt-ex-google-ceo-predicts-internet-split-china.html (accessed November 13, 2018).

10 The RBK Group or RosBiznesKonsalting is a large Russian media group headquartered in Moscow.

11 “Russia Will Create Its Own Internet.” Cyber Security Intelligence Newsletter. January 26, 2018. https://www.cybersecurityintelligence.com/blog/russia-will-create-its-own-internet-3082.html (accessed November 13, 2018).

12 Perry, Tekla. “The Decentralized Internet of HBO’s “Silicon Valley”? Real-World Teams Say They’ve Already Invented It.” IEEE Spectrum. June 9, 2017. https://spectrum.ieee.org/view-from-the-valley/telecom/internet/hbo-silicon-valleys-decentralized-internet-realworld-teams-say-they-already-invented-it (accessed November 13, 2018).

Disclaimer: This is a USASOC G9 Gray Paper that has already been cleared for unlimited release. Distribution is unlimited. The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, U.S. Army Special Operations Command (USASOC), Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

“Quantity has a quality all its own.”

“Quantity has a quality all its own.”

Star Trek Beyond premiered in the summer of 2016, at the height of the U.S.-led campaign to destroy the terrorist group ISIS in Iraq and Syria. At the time, coalition forces were practically paralyzed by just the perception of a threat from ISIS’s

Star Trek Beyond premiered in the summer of 2016, at the height of the U.S.-led campaign to destroy the terrorist group ISIS in Iraq and Syria. At the time, coalition forces were practically paralyzed by just the perception of a threat from ISIS’s

The great powers, including the United States, China, and Russia, have different

The great powers, including the United States, China, and Russia, have different

In the late 1970s, following the end of the Vietnam War, U.S. operational planners started to ponder how to “Fight Outnumbered and Win.” Toward this end, the Army vowed to “Own the Night” – to leverage technology and training to successfully conduct offensive night operations with a level of familiarity and comfort commensurate with daytime operations. Further, nighttime defensive capabilities of other nations were 10 percent of what they would be during the day.

In the late 1970s, following the end of the Vietnam War, U.S. operational planners started to ponder how to “Fight Outnumbered and Win.” Toward this end, the Army vowed to “Own the Night” – to leverage technology and training to successfully conduct offensive night operations with a level of familiarity and comfort commensurate with daytime operations. Further, nighttime defensive capabilities of other nations were 10 percent of what they would be during the day. 1. The proliferation of miniaturized guided munitions and

1. The proliferation of miniaturized guided munitions and  2. Humans are becoming more expensive to recruit, train, and retain, hastening the move to unmanned and robotic systems to replace them, especially for ground forces.

2. Humans are becoming more expensive to recruit, train, and retain, hastening the move to unmanned and robotic systems to replace them, especially for ground forces. 3. Land warfare involves fighting amongst the people, requiring the most demanding performance for autonomous systems in terms of

3. Land warfare involves fighting amongst the people, requiring the most demanding performance for autonomous systems in terms of  4. Future combat operations may occur in

4. Future combat operations may occur in and its allies have held for the past several decades. Highlighting this importance, Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2017 stated that “whoever becomes the leader in this sphere will become the ruler of the world.”

and its allies have held for the past several decades. Highlighting this importance, Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2017 stated that “whoever becomes the leader in this sphere will become the ruler of the world.” Within the past decade,

Within the past decade,

I might have said in a recent

I might have said in a recent  the “greatest long-term national security threat to the U.S.”

the “greatest long-term national security threat to the U.S.”

Desertification and water shortages have meant that the livelihoods of more than five million farmers in Mexico were impacted by the drought from 2002 to 2012. The response was both internal migration to the slums of Mexico City, Guadalajara, and Monterrey and international migration to the United States.

Desertification and water shortages have meant that the livelihoods of more than five million farmers in Mexico were impacted by the drought from 2002 to 2012. The response was both internal migration to the slums of Mexico City, Guadalajara, and Monterrey and international migration to the United States.

seeks to begin clinical trials in 2020 for treatment of particular neurological disorders. Musk also asserts that this technology could and should be available to any individual who wishes to achieve “better access” and “better connections” to “the world, each other, and ourselves.”

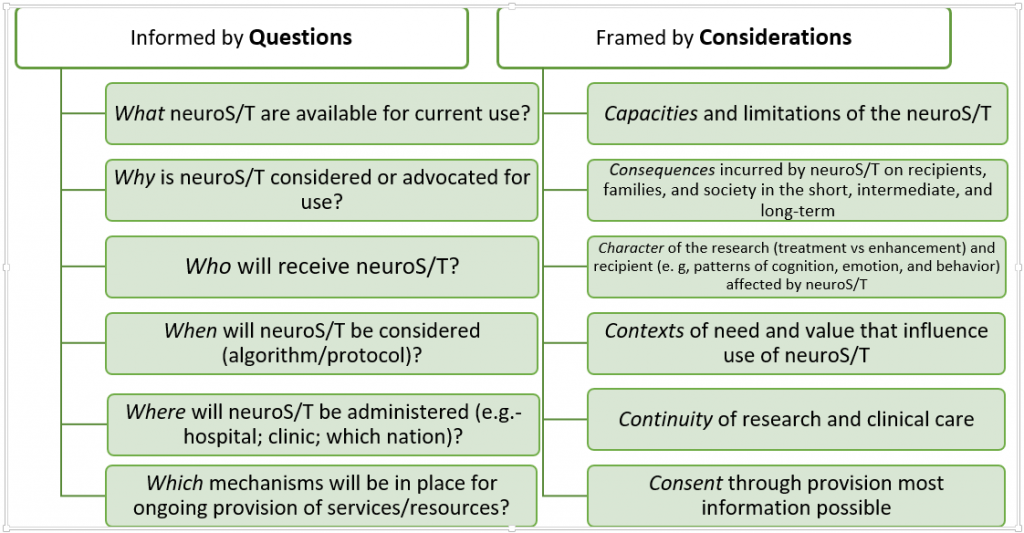

seeks to begin clinical trials in 2020 for treatment of particular neurological disorders. Musk also asserts that this technology could and should be available to any individual who wishes to achieve “better access” and “better connections” to “the world, each other, and ourselves.” neurosurgical intervention to insert the electrodes. And although the level of invasiveness may be reduced, and perhaps increasingly minimized with iterative developments of technology and protocols, inherent neurosurgical risks (e.g., intracranial bleeding; infection) must be recognized. It may well be that the relative benefit-to-burden / risk calculus may support the use of a novel procedure if and when other, extant, and prior interventions are ineffective. Still, we advocate that any such consideration should appreciate and engage questions and contingencies relative to mitigating risks (see Table 1). To wit, what conditions will be treated using this approach; or perhaps more specifically, which patients will receive such treatments?

neurosurgical intervention to insert the electrodes. And although the level of invasiveness may be reduced, and perhaps increasingly minimized with iterative developments of technology and protocols, inherent neurosurgical risks (e.g., intracranial bleeding; infection) must be recognized. It may well be that the relative benefit-to-burden / risk calculus may support the use of a novel procedure if and when other, extant, and prior interventions are ineffective. Still, we advocate that any such consideration should appreciate and engage questions and contingencies relative to mitigating risks (see Table 1). To wit, what conditions will be treated using this approach; or perhaps more specifically, which patients will receive such treatments?

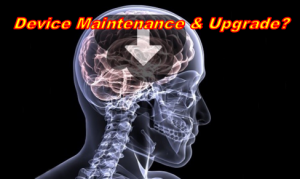

Fourth, given this proposed durability, it is likely that: (1) newer versions of the technology will be developed; and (2) older versions of the technology will require maintenance and updating. Therefore, we ask if and how issues and problems of obsolescence will be addressed and resolved?

Fourth, given this proposed durability, it is likely that: (1) newer versions of the technology will be developed; and (2) older versions of the technology will require maintenance and updating. Therefore, we ask if and how issues and problems of obsolescence will be addressed and resolved? We applaud Neuralink’s strivings to develop cutting-edged therapeutics and respect their view toward neurological optimization. These developments prompt – if not mandate – recognition and acknowledgment of varying cultural needs, values, philosophies, and ethics, as each and all influence receptivity to this and other forms of BMI research and uses-in-practice.

We applaud Neuralink’s strivings to develop cutting-edged therapeutics and respect their view toward neurological optimization. These developments prompt – if not mandate – recognition and acknowledgment of varying cultural needs, values, philosophies, and ethics, as each and all influence receptivity to this and other forms of BMI research and uses-in-practice.