[Editor’s Note: Today’s post by returning guest blogger and proclaimed Mad Scientist Howard R. Simkin was a semi-finalist submission to our Army Mad Scientist Fall/Winter Writing Contest. His intriguing fictional intelligence (FICINT) “narrative within a narrative” — exploring Large Scale Combat Operations in 2040, wrapped within a backcast scenario positing the future of professional military education — helps us to explore how emergent concepts and technologies could be employed and operationalized to enhance future generations of Soldiers’ learning and enable them to win decisively on tomorrow’s battlefields — Read on!]

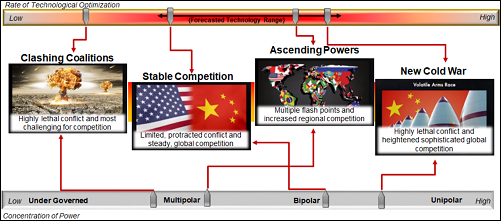

This vignette takes place against the backdrop of Great Power Conflict. On 22 June 2040, the country of Donovia, after months of strained relations and covert hostilities, invades the neighboring country of Otsovia. The United States is a close ally of Otsovia and is compelled to intervene due to treaty obligations and historical ties.

21st SESUi Brigade, Line of Departure – 0700, 14 July 2040

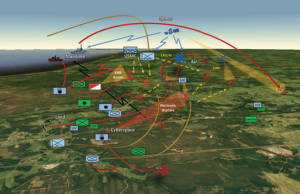

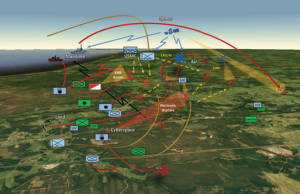

Dispersed, yet continually in touch through LPI/LPDii communications which included magnetic induction, optoelectronic, and quantum, the 21st SESU Brigade was ready to attack with its three maneuver battalions, its IWiii battalion, and other supporting elements. Tactically, technically, and technologically proficient, Colonel Pedro Morales knew how to get the most out of the Soldiers and systems under his command.

The plan was the best that human minds and Artificial Intelligence (AI) could devise, based on literally thousands of battle simulations. Its key was a solid intent to allow Soldiers and systems to maneuver when (not if) communications were degraded.

Morales blinked twice to bring up the status display for his brigade. All battalions were ready, either concealed beneath adaptive camouflage shelters or relying on onboard systems, like the autonomous M1A6’s.

Smiling, Morales thought, “This isn’t my father’s [or mother‘s] M1 Tank.” The M1A6 was fully autonomous, carried a dozen Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS), and bristled with counter-UAS defenses. Since it  had no crew, the turret had been redesigned to lower the tank’s profile. Its metamaterial coating provided adaptive camouflage that reduced the RF and IR signatures of the vehicle, when either stationary or on the move.

had no crew, the turret had been redesigned to lower the tank’s profile. Its metamaterial coating provided adaptive camouflage that reduced the RF and IR signatures of the vehicle, when either stationary or on the move.

In addition to the 120mm hyperglide cannon, it carried three directed energy weapons for all around close-in defense. It also carried enough computing power to run its operations, process the inputs from thousands  of sensors, and direct other combat systems in a fight – all without human intervention. Unlike manned tanks, it had no blind spots, thanks to dozens of sensors located at strategic points around the turret and hull, and an AI enabled cloaking device to defeat multi-spectral scans. In addition, it could network with the other systems and Soldiers in the brigade, forming a formidable kill web.

of sensors, and direct other combat systems in a fight – all without human intervention. Unlike manned tanks, it had no blind spots, thanks to dozens of sensors located at strategic points around the turret and hull, and an AI enabled cloaking device to defeat multi-spectral scans. In addition, it could network with the other systems and Soldiers in the brigade, forming a formidable kill web.

Morales was struck by how few Soldiers were in the maneuver battalions. They manned the three RASCViv that formed the backbone of each augmented  infantry battalion. Essentially an armored computing and communications platform, the RASCV kept humans on the loop, even during fully autonomous operations. It was also a networking node for the dozens of ground and aerial autonomous systems within the battalion that could communicate with LEO satellites as well.

infantry battalion. Essentially an armored computing and communications platform, the RASCV kept humans on the loop, even during fully autonomous operations. It was also a networking node for the dozens of ground and aerial autonomous systems within the battalion that could communicate with LEO satellites as well.

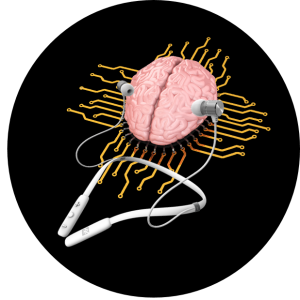

Of course, armored hover carriers took the augmented infantry into battle. Equipped with powered exoskeletons and biologically enhanced, each Soldier  controlled a pair of small UAS for reconnaissance, as well as a pair of robotic quadrupeds nicknamed Cheetahs that were a combination of sensor and gun platform – all linked through a Brain Computer Interface (BCI). “How different things are from when I joined up,” Morales mused.

controlled a pair of small UAS for reconnaissance, as well as a pair of robotic quadrupeds nicknamed Cheetahs that were a combination of sensor and gun platform – all linked through a Brain Computer Interface (BCI). “How different things are from when I joined up,” Morales mused.

A transmission brought Morales back to the present, “Agile Six, this is Agile Three, Over.”

He replied, “Go ahead Three, Over.”

“Six this is Three, everything is ready.”

“Three this is Six, execute.”

The three M1A6 equipped battalions began their dispersed physical maneuver, with the IW battalion maneuvering in the information space. Initially slow to react, the Donovian units began to respond more effectively. Once the edge mesh networked AI analyzed the enemy reaction, it quickly switched tactics to achieve the commander’s intent.

Slicing through the enemy defenses, the brigade received unseen assistance from SOF and resistance elements in the deep areas. Morales found it gratifying to see enemy icons representing C2 nodes and integrated air defense systems change color to orange and then to wink out of existence.

Slicing through the enemy defenses, the brigade received unseen assistance from SOF and resistance elements in the deep areas. Morales found it gratifying to see enemy icons representing C2 nodes and integrated air defense systems change color to orange and then to wink out of existence.

Morales AI Virtual Assistant spoke up, “Sir, 1st Battalion has encountered an unanticipated enemy autonomous tank battalion, the latest Donovian model. They do not believe they can simply bypass and meet your intent. They have requested fire support.”

Surveying the situation quickly he asked, “Recommendations?”

“Two hypercannon batteries are available. They should suffice.”

“Approved.” Morales replied.

Within a few seconds, precision guided hypersonic rounds reduced the enemy tanks to so much junk. The advance continued to gain momentum as the units converged and dispersed at machine speeds. The battle was going well.

In Donovian Airspace, 0701, 14 July 2040

Captain Janet “Bo Peep” Johnson’s F-35 flew into Donovian airspace at 30,000 feet, accompanied by two loyal wingman robotic aircraft. Linked electro-optically and coated with advanced metamaterials, the trio was not picked up by the already disrupted Donovian A2AD network.

Captain Janet “Bo Peep” Johnson’s F-35 flew into Donovian airspace at 30,000 feet, accompanied by two loyal wingman robotic aircraft. Linked electro-optically and coated with advanced metamaterials, the trio was not picked up by the already disrupted Donovian A2AD network.

Spotting a Donovian tank unit uncoiling from a previously undetected laager, Johnson smiled. Using her BCI and retinal implants, she searched through the available integrated fire solutions available. Her personal AI assistant presented the top three options.

Johnson selected an Allied Frigate offshore to strike. With a series of eye movements, she sent what was on her radar screen to the ship’s hypersonic cruise missile system via the mesh-networked CubeSat satellite constellation overhead. With the coordinates locked in, Johnson gave the command to launch.

Johnson selected an Allied Frigate offshore to strike. With a series of eye movements, she sent what was on her radar screen to the ship’s hypersonic cruise missile system via the mesh-networked CubeSat satellite constellation overhead. With the coordinates locked in, Johnson gave the command to launch.

Onboard the frigate, the missiles roared into life without any human interaction. They streaked toward the Donovian unit at Mach 6, receiving last minute targeting data from the loyal wingmen via electro-optical links. The missiles acquired their targets, covered the last bit of distance, and reduced the Donovia armor to twisted piles of smoking scrap metal.

Onboard the frigate, the missiles roared into life without any human interaction. They streaked toward the Donovian unit at Mach 6, receiving last minute targeting data from the loyal wingmen via electro-optical links. The missiles acquired their targets, covered the last bit of distance, and reduced the Donovia armor to twisted piles of smoking scrap metal.

Satisfied with the results, Johnson sent a battle damage report. “A sensor’s work is never done,” she reflected with a smile before beginning to search for more targets.

Charge of the Autonomous Brigades, 0900 20 September 2050

The vignette concludes in a West Point holographic classroom, in the year 2050. The cadets are studying “The Charge of the Autonomous Brigade.”

Captain Yazmin Achmed watched the four yearlings file into the classroom around the central holographic display. Once all stations were green on her retinal display, Achmed stepped to her station.

“Cadets, you are here to study a battle that changed the way warfare is fought. Before we begin the holo-simulation,” she fixed her eye on the Cadet closest to her on the right, “Cadet Jameson, please provide us with a summary.”

Jameson paused before speaking, “The battle took place on 14 July 2040. It involved the US 1st Autonomous Brigade versus the 34th Donovian Mechanized Infantry Division. It led to the almost total elimination of humans from the battlefield. It was the first time that the US employed a totally autonomous brigade in battle.”

Jameson paused before speaking, “The battle took place on 14 July 2040. It involved the US 1st Autonomous Brigade versus the 34th Donovian Mechanized Infantry Division. It led to the almost total elimination of humans from the battlefield. It was the first time that the US employed a totally autonomous brigade in battle.”

“And…?” The Captain prompted.

“The result was the near annihilation of the Donovian unit without the loss of a single U.S. Soldier.”

“Very well.” Captain Achmed turned to the closest Cadet on her left, “Cadet Chou, why did the battle earn the name, ‘The Charge of the Autonomous Brigade’”?

Chou replied immediately, “It was because the speed of advance resembled a cavalry charge before the Industrial Age. Every decision was made at machine speed. The brigade just flowed through any gap in the enemy defense. It never even slowed down appreciably. They achieved complete decision advantage.”

“Excellent.” The Captain said with a smile. “Can anyone summarize the factors that enabled such a success?”

Cadet Garcia at the end of the display table raised his hand.

“Cadet Garcia.”

“First and foremost, it was the overall design of the brigade. Using a hybrid computing architecture ensured that units in contact could make decisions with minimum latency. Our use of intent to guide our AI as it directed operations was crucial. It was something that an enemy wedded to centralized control simply couldn’t match. Additionally, our AI was superior as we had eliminated most sources of bias. It was also explainable, so our leaders had confidence it could function on its own within ethical and legal boundaries.”

He paused a moment before continuing, “We made good use of older systems, many of them taken from boneyards. Once they were retrofitted with AI, sensors, QComms, and computing power, they became cheap and effective weapons delivery platforms.”

Captain Achmed smiled as she interrupted, “Are you suggesting the brigade was a collection of cast-off junk?”

“No ma’am,” Cadet Garcia shook his head emphatically, “We had plenty of new gear, but the use of older platforms enabled us to field the brigade far sooner than would have been otherwise possible.”

“Very good.” The Captain said with a smile. “It appears you have all been keeping up with your assignments.” She nodded to the Cadet opposite Garcia, “Cadet Khan, please run the historical simulation… with commentary.”

Khan straightened up, “Yes Ma’am.” He made a few gestures over the holo-table and the simulation began to run. “As you can see, the enemy was surprised initially…”

If you enjoyed this post, check out the following insightful posts by Howard R. Simkin: CRISPR Convergence, Splinternets, and Sine Pari

… as well as the following related content:

Realer than Real: Useful Fiction with P.W. Singer and August Cole and associated podcast; Weaponized Information: One Possible Vignette; Three Best Information Warfare Vignettes; Two Vignettes: How Might Combat Operations be Different under the Information Joint Function? by proclaimed Mad Scientist Dr. Christopher Paul; and Located, Isolated, and Distracted – An Infantry Platoon Leader’s Experience, by proclaimed Mad Scientist COL Scott Shaw

Algorithms of Armageddon with CAPT (Ret.) George Galdorisi and associated podcast; Artificial Intelligence: An Emerging Game-changer; “Own the Night”; How does the Army – as part of the Joint force – Build and Employ Teams to Compete, Penetrate, Disintegrate, and Exploit our Adversaries in the Future?; Insights from the Robotics and Autonomy Series of Virtual Events; Takeaways Learned about the Future of the AI Battlefield; Integrating Artificial Intelligence into Military Operations, by Dr. James Mancillas; and The Convergence: Bringing AI to the Joint Force and associated podcast

The Future of Learning: Personalized, Continuous, and Accelerated; TRADOC 2028; From Legos to Modular Simulation Architectures: Enabling the Power of Future (War) Play, by Jennifer McArdle and Caitlin Dohrman; A New American Way of Training, and associated podcast, with Jennifer McArdle; The Metaverse: Blurring Reality and Digital Lives with Cathy Hackl and associated podcast; and Fight Club Prepares Lt Col Maddie Novák for Cross-Dimension Manoeuvre, by now COL Arnel David, U.S. Army, and Major Aaron Moore, British Army, along with their interview in The Convergence: UK Fight Club – Gaming the Future Army and associated podcast

Cyborg Soldier 2050: Human/Machine Fusion and the Implications for the Future of the DOD and Benefits, Vulnerabilities, and the Ethics of Soldier Enhancement

About the Author: Howard R. Simkin is a Senior Concept Developer in the DCS, G-9 Concepts, Experimentation and Analysis Directorate, U.S. Army Special Operations Command. He has over 40 years of combined military, law enforcement, defense contractor, and government experience. He is a retired Special Forces officer with a wide variety of special operations experience. Within the G9 he analyzes and defines the future operating environment and required capabilities Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF) in support of future concepts development. His subject matter expertise includes analyzing and evaluating historical, current and emerging technology as well as Combined, Joint, Multi-Service, Army and ARSOF organizational initiatives, trends, and concepts to determine the implications for ARSOF units. Mr. Simkin holds a Masters of Administrative Science from the Johns Hopkins University. He is a proclaimed Mad Scientist as well as a certified Project Management Professional. He has written several articles that have been published in Naval History, Small Wars Journal, and the Army’s Mad Scientist Laboratory.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Defense, U.S, Special Operations Command, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC). This is a fictional vignette set in the 2040 – 2050 timeframe. Any resemblance of the characters in this vignette to any person, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

i System-of-systems Enhanced Small Unit (SESU)

ii Low Probability of Intercept/Low Probability of Detection (LPI/LPD)

iii Information Warfare (IW)

iv Robotic Autonomous Systems Coordination Vehicles

COL Stefan Banach (USA-Ret.) is a Distinguished Member of the 75th Ranger Regiment and served in that organization for nine years, culminating with command of the 3rd Ranger Battalion from 2001-2003. He led U.S. Army Rangers during a historic night combat parachute assault into Afghanistan on October 19, 2001, as the “spearhead” for the Global War on Terror. Steve subsequently led U.S. Army Rangers in a second combat parachute assault into Al Anbar Province in western Iraq in 2003. He served with distinction in the U.S. Army from 1983 to 2010. Since then, he has provided executive consulting services to a diverse range of clients at a number of prestigious institutions. Steve Banach also serves as the Director, Army Management Staff College, an element of Army University responsible for “igniting the leadership potential for every Army civilian.”

COL Stefan Banach (USA-Ret.) is a Distinguished Member of the 75th Ranger Regiment and served in that organization for nine years, culminating with command of the 3rd Ranger Battalion from 2001-2003. He led U.S. Army Rangers during a historic night combat parachute assault into Afghanistan on October 19, 2001, as the “spearhead” for the Global War on Terror. Steve subsequently led U.S. Army Rangers in a second combat parachute assault into Al Anbar Province in western Iraq in 2003. He served with distinction in the U.S. Army from 1983 to 2010. Since then, he has provided executive consulting services to a diverse range of clients at a number of prestigious institutions. Steve Banach also serves as the Director, Army Management Staff College, an element of Army University responsible for “igniting the leadership potential for every Army civilian.”

difficult-to-defend, island territories into “

difficult-to-defend, island territories into “

non-state actors who harness and motivate vast numbers of online users to impact the fight for

non-state actors who harness and motivate vast numbers of online users to impact the fight for  The Ukrainian government sponsored the creation of an “IT Army,” consisting of more than 300,000 individuals from all over the world pushing pro-Ukrainian

The Ukrainian government sponsored the creation of an “IT Army,” consisting of more than 300,000 individuals from all over the world pushing pro-Ukrainian where every unit’s or even individual soldier’s actions and movements may be detected and broadcast. Ukraine has used

where every unit’s or even individual soldier’s actions and movements may be detected and broadcast. Ukraine has used  and

and  solidifying

solidifying  the ethnic Russian diaspora, and some

the ethnic Russian diaspora, and some  Ukraine has set a precedent where gaining international and public support will likely depend on a military’s willingness to show candor by engaging in an open and transparent battlefield, but is it possible to contain and manage a conflict in an open, online domain where militaries and non-state participants exist in the same space? Ukraine has paved the way for engaging civilian support and actions to influence conflicts through digital participation, but how far can civilian actors go and still be protected as noncombatants per the

Ukraine has set a precedent where gaining international and public support will likely depend on a military’s willingness to show candor by engaging in an open and transparent battlefield, but is it possible to contain and manage a conflict in an open, online domain where militaries and non-state participants exist in the same space? Ukraine has paved the way for engaging civilian support and actions to influence conflicts through digital participation, but how far can civilian actors go and still be protected as noncombatants per the  Geneva Conventions? Answering this may prove challenging for the U.S. Army as it tries to navigate an ambiguous, uncertain battlefield where the lines between combatant and non-combatant are blurred. Can choosing to use the flexibility offered by crowdsourcing intelligence information from civilians and private infrastructure negate their protected status? Nations with little interest in adhering to international law may ignore or leverage their civilians’ digital actions against protected U.S. affiliated individuals and infrastructure. How will the U.S. approach its own citizens who take such actions against an adversary

Geneva Conventions? Answering this may prove challenging for the U.S. Army as it tries to navigate an ambiguous, uncertain battlefield where the lines between combatant and non-combatant are blurred. Can choosing to use the flexibility offered by crowdsourcing intelligence information from civilians and private infrastructure negate their protected status? Nations with little interest in adhering to international law may ignore or leverage their civilians’ digital actions against protected U.S. affiliated individuals and infrastructure. How will the U.S. approach its own citizens who take such actions against an adversary

Gen. Flynn is a native of Middletown, Rhode Island and Distinguished Military Graduate from the University of Rhode Island with a BS in Business Management. General Flynn is a graduate of the Infantry Officer Basic and Advanced Courses at Fort Benning, GA. He holds two master’s degrees, one in National Security and Strategic Studies from the United States Naval War College in Newport, RI, and one in Joint Campaign Planning and Strategy from the National Defense University.

Gen. Flynn is a native of Middletown, Rhode Island and Distinguished Military Graduate from the University of Rhode Island with a BS in Business Management. General Flynn is a graduate of the Infantry Officer Basic and Advanced Courses at Fort Benning, GA. He holds two master’s degrees, one in National Security and Strategic Studies from the United States Naval War College in Newport, RI, and one in Joint Campaign Planning and Strategy from the National Defense University.

There are three types of interoperability: human, technical, and procedural. There are also three dimensions: human, physical, and information. The crossover or intersection between interoperability and dimensions is the human. By focusing on the human dimension and investing in and building human interoperability with our allies and partners, other vital components of interoperability will follow.

There are three types of interoperability: human, technical, and procedural. There are also three dimensions: human, physical, and information. The crossover or intersection between interoperability and dimensions is the human. By focusing on the human dimension and investing in and building human interoperability with our allies and partners, other vital components of interoperability will follow. frameworks. Next, the Army needs to be more data-centric. Finally, our forces need to become transport agnostic for our data.

frameworks. Next, the Army needs to be more data-centric. Finally, our forces need to become transport agnostic for our data.

had no crew, the turret had been redesigned to lower the tank’s profile. Its metamaterial coating provided adaptive camouflage that reduced the RF and IR signatures of the vehicle, when either stationary or on the move.

had no crew, the turret had been redesigned to lower the tank’s profile. Its metamaterial coating provided adaptive camouflage that reduced the RF and IR signatures of the vehicle, when either stationary or on the move. of sensors, and direct other combat systems in a fight – all without human intervention. Unlike manned tanks, it had no blind spots, thanks to dozens of sensors located at strategic points around the turret and hull, and an AI enabled cloaking device to defeat multi-spectral scans. In addition, it could network with the other systems and Soldiers in the brigade, forming a formidable kill web.

of sensors, and direct other combat systems in a fight – all without human intervention. Unlike manned tanks, it had no blind spots, thanks to dozens of sensors located at strategic points around the turret and hull, and an AI enabled cloaking device to defeat multi-spectral scans. In addition, it could network with the other systems and Soldiers in the brigade, forming a formidable kill web. infantry battalion. Essentially an armored computing and communications platform, the RASCV kept

infantry battalion. Essentially an armored computing and communications platform, the RASCV kept  controlled a pair of small UAS for reconnaissance, as well as a pair of robotic quadrupeds nicknamed

controlled a pair of small UAS for reconnaissance, as well as a pair of robotic quadrupeds nicknamed  Slicing through the enemy defenses, the brigade received unseen assistance from

Slicing through the enemy defenses, the brigade received unseen assistance from  Captain Janet “Bo Peep” Johnson’s F-35 flew into Donovian airspace at 30,000 feet, accompanied by two loyal wingman robotic aircraft. Linked electro-optically and coated with advanced metamaterials, the trio was not picked up by the already disrupted Donovian A2AD network.

Captain Janet “Bo Peep” Johnson’s F-35 flew into Donovian airspace at 30,000 feet, accompanied by two loyal wingman robotic aircraft. Linked electro-optically and coated with advanced metamaterials, the trio was not picked up by the already disrupted Donovian A2AD network. Johnson selected an Allied Frigate offshore to strike. With a series of eye movements, she sent what was on her radar screen to the ship’s

Johnson selected an Allied Frigate offshore to strike. With a series of eye movements, she sent what was on her radar screen to the ship’s  Onboard the frigate, the missiles roared into life without any human interaction. They streaked toward the Donovian unit at Mach 6, receiving last minute targeting data from the loyal wingmen via electro-optical links. The missiles acquired their targets, covered the last bit of distance, and reduced the Donovia armor to twisted piles of smoking scrap metal.

Onboard the frigate, the missiles roared into life without any human interaction. They streaked toward the Donovian unit at Mach 6, receiving last minute targeting data from the loyal wingmen via electro-optical links. The missiles acquired their targets, covered the last bit of distance, and reduced the Donovia armor to twisted piles of smoking scrap metal.

Jameson paused before speaking, “The battle took place on 14 July 2040. It involved the US 1st Autonomous Brigade versus the 34th Donovian Mechanized Infantry Division. It led to the almost total elimination of humans from the battlefield. It was the first time that the US employed a

Jameson paused before speaking, “The battle took place on 14 July 2040. It involved the US 1st Autonomous Brigade versus the 34th Donovian Mechanized Infantry Division. It led to the almost total elimination of humans from the battlefield. It was the first time that the US employed a