[Editor’s Note: Army Mad Scientist’s enduring mission is to explore the Operational Environment (OE) and the changing character of warfare on behalf of the Army. Crowdsourcing and Edge Cases are two tools we use to help broaden the Army’s horizons and explore future OE possibilities. Crowdsourcing ideas, thoughts, and concepts from a wide variety of interested individuals assists us in diversifying thought and challenges our assumptions, while Edge Cases help us explore what is at the extreme possible regarding new and emerging technologies — allowing us to contextualize the future.

Today’s post by guest blogger PFC Peter Brenner lies at the convergence of crowdsourcing and edge cases. Cognitive enhancement and the targeting of the human brain — the last frontier — is no longer science fiction. The U.S. Army is exploring Soldier Enhancement via wearables, embeddables,  stimulants, brain gyms, and neuroplasticity. PFC Brenner’s submission to our Fall / Winter Writing Contest helps us understand the state of neuroscientific advancements and alerts us to the potential dual use applications of neurophysiological advances — Read on!]

stimulants, brain gyms, and neuroplasticity. PFC Brenner’s submission to our Fall / Winter Writing Contest helps us understand the state of neuroscientific advancements and alerts us to the potential dual use applications of neurophysiological advances — Read on!]

“Once technological advancements can be used for military purposes and have been used for military purposes, they very immediately and almost necessarily, often violating the commander’s will, cause changes or even transformations in the styles of warfare.” — Friedrich Engels, as cited by Contemporary Chinese Strategists in PLA Daily, May 6, 20191

Since the introduction of the U.S. military apparatus in the 18th century, science and warfare have operated unilaterally to protect and advance the American way of life. As operational environments change over time and threats to the United States continue to evolve, the universal purpose of  western militarism remains unchanged. Our governing ideal is inherent — Freedom, relentlessly defended through our cultural, social, and economic investment in the U.S. Armed Forces. The 20th and 21st centuries have advanced technological innovation through scientific discovery faster than at any point in history, notably in the physics, cyberspace, and space domains. Now, new advancements and realizations in the neuroscientific domain have introduced the profound opportunity to characterize the soul of democracy by forcing us to reevaluate how American militarism should implement neurological science and development. We must again decide, as a coalition, where the boundary lines will be drawn between the potential of a new frontier and the risks presented from adversarial necessity to dominate that frontier. Unprecedentedly, the state of the mind is not a frontier of space and time. What has been called “the last frontier”2 returns threats to the United States and our people’s sovereignty back down to earth. For the continued protection, assurance, progression, and affluence of the American way of life, we must acknowledge that the neuroscientific operational environment is a domain of persons. The future of competition and conflict is fundamentally, human.

western militarism remains unchanged. Our governing ideal is inherent — Freedom, relentlessly defended through our cultural, social, and economic investment in the U.S. Armed Forces. The 20th and 21st centuries have advanced technological innovation through scientific discovery faster than at any point in history, notably in the physics, cyberspace, and space domains. Now, new advancements and realizations in the neuroscientific domain have introduced the profound opportunity to characterize the soul of democracy by forcing us to reevaluate how American militarism should implement neurological science and development. We must again decide, as a coalition, where the boundary lines will be drawn between the potential of a new frontier and the risks presented from adversarial necessity to dominate that frontier. Unprecedentedly, the state of the mind is not a frontier of space and time. What has been called “the last frontier”2 returns threats to the United States and our people’s sovereignty back down to earth. For the continued protection, assurance, progression, and affluence of the American way of life, we must acknowledge that the neuroscientific operational environment is a domain of persons. The future of competition and conflict is fundamentally, human.

Neuroscience, or the scientific study of the nervous system,3 is not only not new, but dates back to at least 17th century B.C. Egypt.4 We, as a species, have long wondered what is the metaphysical “meaning of life.” It wasn’t until the  2nd century that the forefather of neuroscience, Galen, argued that the brain is the central organ that governs bodily function and not the heart.5 Fast forward 1600 years to the 19th century and phrenology, or the pseudoscience of the mind, is introduced in Austria.6 While off course as with most early biological explanations, phrenology introduced us to the prospect that different regions of the brain are correlated to different human behaviors.7 X-rays are accidentally discovered about a hundred years later,8 shining a light on how we, as living things, interact with the complex forces that exist around and within us. Along with its perceived invasiveness, x-ray imaging revolutionized the efficiency of medical treatment.9 It was then proselytized in the 1940s that regions of the brain could be isolated using x-ray-based positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).10 Our understanding of the brain neared

2nd century that the forefather of neuroscience, Galen, argued that the brain is the central organ that governs bodily function and not the heart.5 Fast forward 1600 years to the 19th century and phrenology, or the pseudoscience of the mind, is introduced in Austria.6 While off course as with most early biological explanations, phrenology introduced us to the prospect that different regions of the brain are correlated to different human behaviors.7 X-rays are accidentally discovered about a hundred years later,8 shining a light on how we, as living things, interact with the complex forces that exist around and within us. Along with its perceived invasiveness, x-ray imaging revolutionized the efficiency of medical treatment.9 It was then proselytized in the 1940s that regions of the brain could be isolated using x-ray-based positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).10 Our understanding of the brain neared  its current state — a mostly mathematical system of neural circuitry working in tandem to produce electrical activity, or behavior. In the 1990s, scientists discovered that functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), could be used to translate behavioral functions into neural imaging. Scientists have even started learning how to accomplish the opposite.11 By the 21st century, we had achieved what we once thought impossible. The method of accurately interpreting how chemical and electrical reactions within the brain correlate to the actions, choices, feelings, and even the thoughts, of people,12 had been discovered. As Professor of Law Stacey A. Tovino posited in 2007 in the American Journal of Law & Medicine, fMRI provided (and continues to provide) comprehension to “personal-decision making.”13 This is the basic history of a one dimensional understanding of our brains. A dimension that has given life to a still-new science that has exploded since the 1990s, helping us understand how neural computation results in the behaviors that we experience every day as we interact in our respective worlds. Most strikingly, neuroscience has opened a window into the multidimensional pseudo-construct that we define as the mind.

its current state — a mostly mathematical system of neural circuitry working in tandem to produce electrical activity, or behavior. In the 1990s, scientists discovered that functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), could be used to translate behavioral functions into neural imaging. Scientists have even started learning how to accomplish the opposite.11 By the 21st century, we had achieved what we once thought impossible. The method of accurately interpreting how chemical and electrical reactions within the brain correlate to the actions, choices, feelings, and even the thoughts, of people,12 had been discovered. As Professor of Law Stacey A. Tovino posited in 2007 in the American Journal of Law & Medicine, fMRI provided (and continues to provide) comprehension to “personal-decision making.”13 This is the basic history of a one dimensional understanding of our brains. A dimension that has given life to a still-new science that has exploded since the 1990s, helping us understand how neural computation results in the behaviors that we experience every day as we interact in our respective worlds. Most strikingly, neuroscience has opened a window into the multidimensional pseudo-construct that we define as the mind.

As with the implementation of x-ray technology into the public sphere of influence, the questions of security and privacy were raised as scientists realized neuroscience and technological innovation could revolutionize how we examine the interconnected behavioral processes that result in intraspecies interaction. As we peered deeper into the brain, neuroscientific principals began challenging the core conceptualizations of what defines one as an  individual.14 Interactive behavioral mechanisms are communicative,15 they are sharable,16 and are subject to civil discourse.17 Individual behavior is private,18 conserved,19 and generally in the interests of the person.20 This behavioral dichotomy between what categorizes behavior as psychosocial and instinctively “of the self” is the complicated riddle that makes us human. Our individual differences contrasted with our social interactions, operating from the base of cognition, are characterizations that make us inherently social beings.

individual.14 Interactive behavioral mechanisms are communicative,15 they are sharable,16 and are subject to civil discourse.17 Individual behavior is private,18 conserved,19 and generally in the interests of the person.20 This behavioral dichotomy between what categorizes behavior as psychosocial and instinctively “of the self” is the complicated riddle that makes us human. Our individual differences contrasted with our social interactions, operating from the base of cognition, are characterizations that make us inherently social beings.

The western military apparatus, that is the U.S. Armed Forces and the militaries of our closest allies, exemplifies this behavioral Catch-22 in form and function. The entire premise of mission success through team-oriented task  diversification augments individual interest.21 In other words, militaries are team constructs for a reason. However, new discoveries in the neurosciences are presenting unparalleled insight into higher dimensional capabilities. Experiments utilizing fMRI have shown that scientists reading brain scans can predict what number a subject will select before the number is selected.22 Similarly, when shown unfamiliar faces, scientists can predict how a subject will react based off of unconscious neural fireworks a subject isn’t even aware they are emitting.23 Insights into the cognitive innerworkings of an individual’s motivations could call into question the integrity of individualization and socialization, especially as biodata is compiled in large quantities, by populations, saved over long periods of time, and strategically

diversification augments individual interest.21 In other words, militaries are team constructs for a reason. However, new discoveries in the neurosciences are presenting unparalleled insight into higher dimensional capabilities. Experiments utilizing fMRI have shown that scientists reading brain scans can predict what number a subject will select before the number is selected.22 Similarly, when shown unfamiliar faces, scientists can predict how a subject will react based off of unconscious neural fireworks a subject isn’t even aware they are emitting.23 Insights into the cognitive innerworkings of an individual’s motivations could call into question the integrity of individualization and socialization, especially as biodata is compiled in large quantities, by populations, saved over long periods of time, and strategically  put to use. While being able to consider unconscious behavior is undoubtedly operationally advantageous, this greater understanding in the hands of our adversaries could be used to manipulate and threaten the American way of life, without them ever needing to launch a kinetic attack.

put to use. While being able to consider unconscious behavior is undoubtedly operationally advantageous, this greater understanding in the hands of our adversaries could be used to manipulate and threaten the American way of life, without them ever needing to launch a kinetic attack.

The question of whether neuroscientific advancements should be implemented into warfare is an extensive conversation which presents compelling arguments for both sides, similar to the introduction of nuclear physics into weapons proliferation.  The most pragmatic argument for neuro-based research and development is that it is already happening and often not by allies of the United States.24 Biochemical warfare is not a new concept. The use of weapons to target the nervous system of enemies saw barbarous use in World Wars I & II25 and continues to be used by the West’s most dangerous adversaries.26 While more regulated, the United States also wields neurophysiological principals in operations. Cognition is fundamentally the domain of psychological warfare.27 While still in its fledgling phase, the “brain race” is on to see who can best maneuver in the operational domain that comprises consciousness.

The most pragmatic argument for neuro-based research and development is that it is already happening and often not by allies of the United States.24 Biochemical warfare is not a new concept. The use of weapons to target the nervous system of enemies saw barbarous use in World Wars I & II25 and continues to be used by the West’s most dangerous adversaries.26 While more regulated, the United States also wields neurophysiological principals in operations. Cognition is fundamentally the domain of psychological warfare.27 While still in its fledgling phase, the “brain race” is on to see who can best maneuver in the operational domain that comprises consciousness.

Beyond its currently limited practical use, the future of militarism could be influenced by neuroscience positively. Genetic enhancement presents enticing opportunities to improve force quality through supplementation, prospectively even genetic modification.28 Like exercising a muscle or practicing with a weapon, the cognitive skillsets of Service members could be increased by enhancing the brain.29 A more informed and therefore more cognitively capable Armed Forces is promoted by investing in the educations of Service members, veterans, and their families. Cognitive deficiencies and mood disorders, such as ADHD and depression, are treated with prescription medication, targeting chemical compounds in the brain.30 Neuroscientific experimentation could even help us find the exact locations of the brain that produce life-altering behavioral disorders such as PTSD.31 The limits to force enhancement are unknown, but the best asset to winning war and achieving mission success remains mental toughness.32

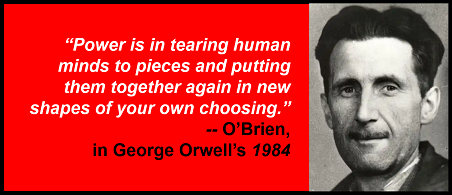

The negative influences and risks of uncharted neuroscientific experimentation are vast. Bioethicists such as Paul Root Wolpe, Editor-In-Chief of AJOB Neuroscience, the official Journal of the International Neuroethics Society (INS), submitted a clarion objection to the judicial, justifiable, militarized, or commercialized use of any technology that could invade “our single most private possession” in a 2009 Forbes Opinions piece entitled “Is My Mind Mine?”33 The simple truth is it is not yet understood what ancillary effects could result from a deeper exploration into the kaleidoscopic dimensions of neurocognition. It cannot always be forecasted what we will unearth when pushing the boundaries of exploration into new scientific domains. Scientists don’t even understand how brain matter can house the complex electrical circuitry which transfers signals throughout the brain.34 Furthermore, the neuroscientific domain is not inherently militaristic, unlike rocket science.35 Neuroscientific breakthroughs have been occurring outside of military laboratories,36 which means democratic militarism must traverse the diplomatically knotty minefield of dual-use science if cognition will be weaponized.37 For the good of democracy, our minds may be best left locked.

It is critical that the U.S. Armed Forces unite with the scientific community to discern the threat posed to democracy by the neurophysiological capabilities of adversarial threats. The solution to upholding democratic ideals, starting with U.S. militarism, will likely hinge on our reliance on international accord. As a global community, we need to agree on the difference between neuroscientific experimentation and endangering individual cognitive sovereignty. As Wolpe posits in his article, “To keep silent even in the face of torture or death is humanity’s most powerful, final act of will. What if that ability were to be lost? What if that final freedom is taken away and information can be taken from a person despite their act of resistance? Something precious will have been lost to the human condition because our inner lives will no longer be ours alone.”38

If you enjoyed this post, check out the following related content:

Dr. James Giordano‘s presentation on Neurotechnology in National Security and Defense, from the Mad Scientist Visioning Multi Domain Battle in 2030-2050 Conference at Georgetown University in Washington, DC, on 25 & 26 July 2017; and his Neuroscience and the Weapons of War podcast, hosted by our colleagues at Modern War Institute (MWI), 2 August 2017.

Top Ten Bio Convergence Trends Impacting the Future Operational Environment, Bio Convergence and Soldier 2050 Conference Final Report, and the comprehensive Final Report from the Mad Scientist Bio Convergence and Soldier 2050 Conference with SRI International on 8–9 March 2018 at their Menlo Park campus in California

Cyborg Soldier 2050: Human/Machine Fusion and the Implications for the Future of the DOD, and the comprehensive report from which it was sourced.

Linking Brains to Machines, and Use of Neurotechnology to the Cultural and Ethical Perspectives of the Current Global Stage, by Mr. Joseph DeFranco and Dr. James Giordano.

China’s Brain Trust: Will the U.S. Have the Nerve to Compete? by Mr. Joseph DeFranco, CAPT (USN – Ret.) L. R. Bremseth, and Dr. James Giordano

Sub-threshold Maneuver and the Flanking of U.S. National Security, by Dr. Russell Glenn

Battle of the Brain

Connected Warfare by COL James K. Greer (USA-Ret.)

In the Cognitive War – The Weapon is You! by Dr. Zac Rogers

About the Author: PFC Peter Brenner is an up and coming U.S. Army Intelligence Analyst. When not conducting his intelligence duties, Brenner is pursuing his Bachelor’s of Applied Science in Administration of Justice from the University of Arizona showcasing his premier range and scope of knowledge. Originally from New York, Brenner is a strong advocate for everyone being informed and finding their own connection in the world through knowledge.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

List of References

1, 24 Kania, E. (2019). Minds at War. PRISM, Vol. 8 (No. 3), Washington, D.C.: Institute for National Strategic Security, National Defense University. 82-101.

2 Tibbets, P. (2016). Sociology and Neuroscience: An Emerging Dialogue. The American Sociologist, Vol. 47 (No. 1), Switzerland: Springer. 36-46.

3 About Neuroscience, Department of Neuroscience: Georgetown University. Retrieved from https://neuro.georgetown.edu/about-neuroscience/.

4 Mohamed, W. (2008). The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus: Neuroscience in Ancient Egypt. IBRO History of Neuroscience. International Brain Research Organization Retrieved from https://archive.ph/20140706060915/http:/www.ibro1.info/Pub/Pub_Main_Display.asp?LC_Docs_ID=3199.

5 Freemon, F. (1994). Galen’s ideas on neurological function. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, 3 (4). 263-271. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11618827/.

6-10, 13 Tovino, S. (2007). Imaging Body Structure and Mapping Brain Function: A Historical Approach. American Journal of Law & Medicine, 33, Boston: Boston University of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 193-228.

11 Ward, J. (2015). Chapter 4: The imaged brain. The Student’s Guide to Cognitive Neuroscience, Third Edition, London: Taylor & Francis Ltd. 49-79.

12, 14 Roskies, A. (2015). Mind Reading, Lie Detection, and Privacy. Handbook of Neuroethics, J. Clausen, N. Levy eds, Dordrecht: Springer Science + Business Media. 679-695

15, 16 Robinson, G., Fernald, R. & Clayton, D. (2008). Genes and Social Behavior. Science, 322 (5903), National Institute of Health. 896-900.

17 Baez, S., Garcia, A. & Ibanez, A. (2018). How Does Social Context Influence Our Brain and Behavior? Frontiers for Young Minds. Retrieved from https://kids.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frym.2018.00003.

18, 19 Wolpe, P. (2009). Is My Mind Mine? Forbes. Retrieved from

33, 38. https://www.forbes.com/2009/10/09/neuroimaging-neuroscience-mind-reading- opinions-contributors-paul-root-wolpe.html#287692d86147.

20 Faulhaber, R. (2005). The Rise and Fall of “Self-Interest.” Review of Social Economy, Vol. 63 (No. 3), London: Taylor & Francis. 405-422.

21 Blacksmith, N., Coats, M. & Goodwin, G. (2018). The Science of Teams in the Military: Contributions From Over 60 Years of Research. American Psychologist, Vol. 73 (No. 4), American Psychological Association. 322-333.

22 Brass, M., Haynes, J., Heinze, H. & Soon, C. (2008). Unconscious determinants of free decisions in the human brain. Nature neuroscience, Vol. 11, Berlin: Nature Publishing Group. 543-545.

23 Castello, M., Gobbini, I., Gors, J. & Halchenko, Y. (2017). The neural representation of personally familiar and unfamiliar faces in the distributed system for face perception. Scientific Reports, Vol. 7. Basingtoke: Springer Nature. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12559-1.

25 Frischknecht, F. (2003). The history of biological warfare. EMBO reports, Vol. 4 (Special Issue), Bethesda: National Center or Biotechnology Information. S47-S52.

26 Corera, G. (2021). ‘Havana syndrome’ and the mystery of the microwaves. BBC News, Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-58396698.

27 About the U.S. Army Psychological Operations Regiment, U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School. Retrieved from https://www.soc.mil/SWCS/IMSO/aboutPSYOP.htm.

28 DeFranco, J., DiEuliis, D. & Giordano J. (2019). Redefining Neuroweapons. PRISM, Vol. 8 (No. 3), Washington, D.C.: Institute for National Strategic Security, National Defense University. 48-63.

29 Sandel, M. (2004). The Case Against Perfection. The Atlantic, (No. Apr ’04), Washington, D.C: The Atlantic Monthly Group. 50-63.

30 Mohamed, A. (2014). Neuroethical issues in pharmacological cognitive enhancement. WIREs Cognitive Science, Vol. 5, Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 533-549.

31 Guangming, L., Jun, L., Li, Z., Lingjiang, L., Liwen, T., Rongfeng, Q. & Weihui, L. (2013). Brain structure in post-traumatic stress disorder. Neural Regeneration Research, Vol. 8 (No. 26), China: Publishing House of Neural Regeneration. 2405-2414.

32 Arthur, C., Fitzwater, J. & Hardy, L. (2017). “The Tough Get Tougher”: Mental Skills Training With Elite Military Recruits. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, Vol. 7 (No. 1), Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. 93-107.

34 Newman, J. & Revonsuo, A. (1999). “Binding and Consciousness.” Consciousness and Cognition, Vol. 8, Amsterdam: Elsevier. 123-127.

35-37 Kosal, M. & Huang, J. (2015). “Security implications and governance of cognitive neuroscience: An ethnographic survey of researchers.” Politics and the Life Sciences, Vol. 34 (No. 1), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 93-108.

The all-volunteer force is at risk. Demographic trends show that the population of individuals qualified for recruitment is diminishing. Finding the “Secret Sauce” that motivates people to serve and stay in the Army will be vital to ensuring the Nation’s Senior Service remains an effective and capable force.

The all-volunteer force is at risk. Demographic trends show that the population of individuals qualified for recruitment is diminishing. Finding the “Secret Sauce” that motivates people to serve and stay in the Army will be vital to ensuring the Nation’s Senior Service remains an effective and capable force. Education is the best tool to prepare our Soldiers, and should be prioritized at every echelon. Strong doctrine can help form successful training programs and modernize the Soldier to out-think our adversary. Such education should also teach ‘disciplined disobedience,’ enabling Soldier-Innovators to adapt creatively to ensure mission success.

Education is the best tool to prepare our Soldiers, and should be prioritized at every echelon. Strong doctrine can help form successful training programs and modernize the Soldier to out-think our adversary. Such education should also teach ‘disciplined disobedience,’ enabling Soldier-Innovators to adapt creatively to ensure mission success. The adage that “it requires 10,000 hours” to master a task reigns true in military training. Synthetic training environments can facilitate necessary practice on critical tasks, but should not entirely replace live training exercises.

The adage that “it requires 10,000 hours” to master a task reigns true in military training. Synthetic training environments can facilitate necessary practice on critical tasks, but should not entirely replace live training exercises. There are four audiences of information in every conflict: the leadership of one’s own country, the Soldiers and families of our military, our allies and partners, and our adversaries. Successfully navigating the distribution of information to these groups will remain paramount to mission success.

There are four audiences of information in every conflict: the leadership of one’s own country, the Soldiers and families of our military, our allies and partners, and our adversaries. Successfully navigating the distribution of information to these groups will remain paramount to mission success. Stay tuned to the Mad Scientist Laboratory for our next episode of The Convergence podcast featuring General Charles E. Flynn, Commanding General, U.S.

Stay tuned to the Mad Scientist Laboratory for our next episode of The Convergence podcast featuring General Charles E. Flynn, Commanding General, U.S.  Army Pacific (USARPAC), discussing the unique pacing threat posed by China, building interoperability with partner nations, and the future of multi-domain operations in INDOPACOM.

Army Pacific (USARPAC), discussing the unique pacing threat posed by China, building interoperability with partner nations, and the future of multi-domain operations in INDOPACOM.

In 2018, the U.S. Army published its concept for Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) through 2028. The

In 2018, the U.S. Army published its concept for Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) through 2028. The  Though the U.S. military has been a volunteer organization since

Though the U.S. military has been a volunteer organization since  Instead, it should assume that recruitment and retention will only become more challenging and should acknowledge the myriad of threats that are emerging to the maintenance an all-volunteer force.

Instead, it should assume that recruitment and retention will only become more challenging and should acknowledge the myriad of threats that are emerging to the maintenance an all-volunteer force.

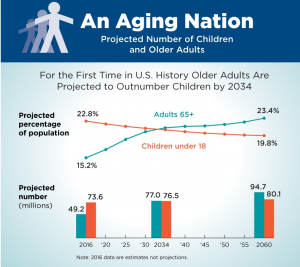

The threat of an aging population to military recruitment has been extensively explored, often referencing Japan as a case study. In 2021, the ratio of Japan’s population under age 14

The threat of an aging population to military recruitment has been extensively explored, often referencing Japan as a case study. In 2021, the ratio of Japan’s population under age 14  its recruitment targets

its recruitment targets only recruiting 7,340 new members in October and November 2021. The Army recently announced it is offering a bonus of up to $50,000, the largest amount ever, to some new recruits who enlist for six years.” When combined with the following trends, this shortcoming is even more disconcerting.

only recruiting 7,340 new members in October and November 2021. The Army recently announced it is offering a bonus of up to $50,000, the largest amount ever, to some new recruits who enlist for six years.” When combined with the following trends, this shortcoming is even more disconcerting. Already,

Already,

The military currently makes up less than

The military currently makes up less than  distrust in government institutions overall, but particularly in foreign policy. In 2021,

distrust in government institutions overall, but particularly in foreign policy. In 2021,  onger be

onger be

with fewer people.

with fewer people.  asthma. While some of these conditions can be bypassed with

asthma. While some of these conditions can be bypassed with  system can help the military promote transparency and accountability within itself, both of which positively impact

system can help the military promote transparency and accountability within itself, both of which positively impact  Soldier (i.e., a combatant) versus a non-combatant. The Army’s

Soldier (i.e., a combatant) versus a non-combatant. The Army’s  If you enjoyed this post, read

If you enjoyed this post, read

Steven Leonard

Steven Leonard

stimulants,

stimulants,  western militarism remains unchanged. Our governing ideal is inherent — Freedom, relentlessly defended through our cultural, social, and economic investment in the U.S. Armed Forces. The 20th and 21st centuries have advanced

western militarism remains unchanged. Our governing ideal is inherent — Freedom, relentlessly defended through our cultural, social, and economic investment in the U.S. Armed Forces. The 20th and 21st centuries have advanced 2nd century that the forefather of neuroscience, Galen, argued that the brain is the central organ that governs bodily function and not the heart.5 Fast forward 1600 years to the 19th century and phrenology, or the pseudoscience of the mind, is introduced in Austria.6 While off course as with most early biological explanations, phrenology introduced us to the prospect that different regions of the brain are correlated to different human behaviors.7 X-rays are accidentally discovered about a hundred years later,8 shining a light on how we, as living things, interact with the complex forces that exist around and within us. Along with its perceived invasiveness, x-ray imaging revolutionized the efficiency of medical treatment.9 It was then proselytized in the 1940s that regions of the brain could be isolated using x-ray-based positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).10 Our understanding of the brain neared

2nd century that the forefather of neuroscience, Galen, argued that the brain is the central organ that governs bodily function and not the heart.5 Fast forward 1600 years to the 19th century and phrenology, or the pseudoscience of the mind, is introduced in Austria.6 While off course as with most early biological explanations, phrenology introduced us to the prospect that different regions of the brain are correlated to different human behaviors.7 X-rays are accidentally discovered about a hundred years later,8 shining a light on how we, as living things, interact with the complex forces that exist around and within us. Along with its perceived invasiveness, x-ray imaging revolutionized the efficiency of medical treatment.9 It was then proselytized in the 1940s that regions of the brain could be isolated using x-ray-based positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).10 Our understanding of the brain neared  its current state — a mostly mathematical system of neural circuitry working in tandem to produce electrical activity, or behavior. In the 1990s, scientists discovered that functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), could be used to translate behavioral functions into neural imaging. Scientists have even started learning how to accomplish the opposite.11 By the 21st century, we had achieved what we once thought impossible. The method of accurately interpreting how chemical and electrical reactions within the brain correlate to the actions, choices, feelings, and even the thoughts, of people,12 had been discovered. As Professor of Law Stacey A. Tovino posited in 2007 in the American Journal of Law & Medicine, fMRI provided (and continues to provide) comprehension to “personal-decision making.”13 This is the basic history of a one dimensional understanding of our brains. A dimension that has given life to a still-new science that has exploded since the 1990s, helping us understand how neural computation results in the behaviors that we experience every day as we interact in our respective worlds. Most strikingly, neuroscience has opened a window into the multidimensional pseudo-construct that we define as the mind.

its current state — a mostly mathematical system of neural circuitry working in tandem to produce electrical activity, or behavior. In the 1990s, scientists discovered that functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), could be used to translate behavioral functions into neural imaging. Scientists have even started learning how to accomplish the opposite.11 By the 21st century, we had achieved what we once thought impossible. The method of accurately interpreting how chemical and electrical reactions within the brain correlate to the actions, choices, feelings, and even the thoughts, of people,12 had been discovered. As Professor of Law Stacey A. Tovino posited in 2007 in the American Journal of Law & Medicine, fMRI provided (and continues to provide) comprehension to “personal-decision making.”13 This is the basic history of a one dimensional understanding of our brains. A dimension that has given life to a still-new science that has exploded since the 1990s, helping us understand how neural computation results in the behaviors that we experience every day as we interact in our respective worlds. Most strikingly, neuroscience has opened a window into the multidimensional pseudo-construct that we define as the mind. individual.14 Interactive behavioral mechanisms are communicative,15 they are sharable,16 and are subject to civil discourse.17 Individual behavior is private,18 conserved,19 and generally in the interests of the person.20 This behavioral dichotomy between what categorizes behavior as psychosocial and instinctively “of the self” is the complicated riddle that makes us human. Our individual differences contrasted with our social interactions, operating from the base of cognition, are characterizations that make us inherently social beings.

individual.14 Interactive behavioral mechanisms are communicative,15 they are sharable,16 and are subject to civil discourse.17 Individual behavior is private,18 conserved,19 and generally in the interests of the person.20 This behavioral dichotomy between what categorizes behavior as psychosocial and instinctively “of the self” is the complicated riddle that makes us human. Our individual differences contrasted with our social interactions, operating from the base of cognition, are characterizations that make us inherently social beings. diversification augments individual interest.21 In other words, militaries are

diversification augments individual interest.21 In other words, militaries are  put to use. While being able to consider unconscious behavior is undoubtedly operationally advantageous, this greater understanding in the hands of our adversaries could be used to

put to use. While being able to consider unconscious behavior is undoubtedly operationally advantageous, this greater understanding in the hands of our adversaries could be used to  The most pragmatic argument for neuro-based research and development is that it is

The most pragmatic argument for neuro-based research and development is that it is

tailored to the mission of the branch that oversees it. NSIN, however, serves as an innovation catalyst for the entire DoD, seeking to serve each branch and collaborate across the DoD to match

tailored to the mission of the branch that oversees it. NSIN, however, serves as an innovation catalyst for the entire DoD, seeking to serve each branch and collaborate across the DoD to match NSIN provides a guide across the

NSIN provides a guide across the