[Editor’s Note: Army Mad Scientist welcomes returning guest blogger LTC Nathan Colvin with today’s submission, judged as a semi-finalist in our recent Back to the Future Writing Contest. Tackling our writing prompt — How could our future be different than our past experiences and what are the potential surprises or disadvantages? — LTC Colvin’s cautionary piece explores the return of Great Power Conflict, reminding us that the U.S. Army’s current operational concept is Multi-Domain Operations (MDO), not Large-Scale Combat Operations (LSCO). “While conflict in multiple domains is likely, large-scale multi-domain operations remain less likely between two great powers due to the conventional material costs and the slippery slope toward nuclear weapon use.” The Joint Force’s approach to deterrence and conflict must address the full spectrum of operations, as future conflicts are likely to remain hybrid ones. “Assuming that great powers will only fight great wars can lead to death by a thousand cuts while holding a tourniquet” — Read on!]

Introduction

Russian tanks roll across the heart of Europe. China dramatically increases capabilities across all domains. Great powers are back with a vengeance. Analogies drawn from the Cold War and World War II return. Multipolarity challenges the United States’ hegemonic position. Deterrence makes its way back into strategic thought. Great nations with big armies renew conversations about power balancing. Theorists are proud to make realism great again. Like an elastic band snapping into place, Army culture returns to familiar conversations about relative combat power, fires, and maneuver. While certainly the most dangerous form of war, are Large-Scale Combat Operations (LSCO) inevitable amongst great powers?

Russian tanks roll across the heart of Europe. China dramatically increases capabilities across all domains. Great powers are back with a vengeance. Analogies drawn from the Cold War and World War II return. Multipolarity challenges the United States’ hegemonic position. Deterrence makes its way back into strategic thought. Great nations with big armies renew conversations about power balancing. Theorists are proud to make realism great again. Like an elastic band snapping into place, Army culture returns to familiar conversations about relative combat power, fires, and maneuver. While certainly the most dangerous form of war, are Large-Scale Combat Operations (LSCO) inevitable amongst great powers?

My argument is no. While geopolitical dynamics may resemble historical conditions leading to direct great power wars, states are more interdependent than ever, are restricted by the nuclear weapons revolution in military affairs,  and are constrained by the costs of conventional war. The proper lesson from history is that conflict abhors a vacuum, and threats will take advantage of whatever space is available. Therefore, the Army must consider diverse solutions to deter and win in both LSCO and non-LSCO Multi-Domain Operations.

and are constrained by the costs of conventional war. The proper lesson from history is that conflict abhors a vacuum, and threats will take advantage of whatever space is available. Therefore, the Army must consider diverse solutions to deter and win in both LSCO and non-LSCO Multi-Domain Operations.

What’s so great about these powers anyway?

What makes a great power, well, great? Although definitions vary, great powers can exert themselves beyond their near abroad to achieve goals. Today, great power should be able to extend capabilities to a global scale (Bohler 2017) through their level of capability, geographic reach, and be recognized as a great power by other nations (Danilovic 2002). France, United Kingdom, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Japan, United States, Russia/USSR, and China are historical Great Powers.

Great powers interact with the world cooperatively or competitively. When competition between two powers leads to direct military clashes, conflict occurs. Where cooperation occurs, both states benefit from the transaction, while in competition or conflict, one or both powers suffer. The dynamics of these interactions create a hierarchy of states, first formally recognized in the 1814 Concert of Europe.

Realists say that states vie to be the most powerful while limiting other states’ ability to overtake them. The resulting phenomenon of states allying with the leader (bandwagoning) or against them (balancing), is known as balance of power theory (Waltz 1979). When one power is on the rise, another declines – which puts them on a crash course for a zero-sum conflict (Mearsheimer 2010). The current dominant narrative puts China on the rise, Russia trying to rise, and the United States in relative decline (Kroenig 2022). No doubt a recipe for war, right?

Historically speaking, you could argue there is significant proof that great power war is inevitable. After all, since the Concert of Europe, great powers fought each other from the Hundred Days War to World War II. However, during the same period, there were as many small and/or proxy wars as great  power wars. After World War II, the dynamic shifted further as “the resultant Cold War was an approximately 40 year-long political, military and economic confrontation between the USA and the Soviet Union and their respective allies… [that] never escalated into direct military confrontation between the superpowers, but involved an unprecedented arms race with both nuclear and conventional weapons as well as plethora of proxy conflicts”(UCDP 2023). The Korean, Vietnam, and Russian-Afghanistan wars were the closest great powers came to direct conflict, but they remained proxy wars. What can we attribute to this nearly 80-year lack of Great Power Conflict?

power wars. After World War II, the dynamic shifted further as “the resultant Cold War was an approximately 40 year-long political, military and economic confrontation between the USA and the Soviet Union and their respective allies… [that] never escalated into direct military confrontation between the superpowers, but involved an unprecedented arms race with both nuclear and conventional weapons as well as plethora of proxy conflicts”(UCDP 2023). The Korean, Vietnam, and Russian-Afghanistan wars were the closest great powers came to direct conflict, but they remained proxy wars. What can we attribute to this nearly 80-year lack of Great Power Conflict?

(Not) Going Nuclear

In the pre-WW II examples, Great Powers could gain from conflict. Zero-sum outcomes incentivized the use of force and created conditions for increasingly lethal battlefield capabilities. Increased capability extended the scale of vertical escalation possible. This trend continued until the Cold War. The parallel expansion of nuclear arsenals created a new dynamic.  As Bull (1996, 48) points out, “it is only in the context of nuclear weapons and other recent military technology that it becomes pertinent to ask whether war could not now be both ‘absolute in the results’ and take the form of a ‘single instantaneous blow’ in Clausewitz’s understanding of those terms.” In other words, nuclear weapons “capped” the escalation race, especially once stockpiles ensured Mutually Assured Destruction. At that point, winner-takes-all possibilities shifted to a likely lose-lose situation.

As Bull (1996, 48) points out, “it is only in the context of nuclear weapons and other recent military technology that it becomes pertinent to ask whether war could not now be both ‘absolute in the results’ and take the form of a ‘single instantaneous blow’ in Clausewitz’s understanding of those terms.” In other words, nuclear weapons “capped” the escalation race, especially once stockpiles ensured Mutually Assured Destruction. At that point, winner-takes-all possibilities shifted to a likely lose-lose situation.

If vertical escalation is capped, what are other choices? Investments in hypersonics, long-range precision fires, future vertical lift, space, and cyber capabilities extend geographic range, supporting horizontal escalation options. Alternatively, great powers could avoid military confrontation with each other, instead choosing to escalate both vertically and horizontally in the diplomatic, informational, and economic elements of national power. In the Cold War, that led to the exclusive use of proxies. Today, adversaries take advantage of complex interdependence to employ “hostile acts outside the realm of armed conflict to weaken a rival country, entity, or alliance” known as gray-zone aggression (Braw 2022). This leads to a sort of “diagonal escalation.”

There will not be (and probably never have been) purely conventional or unconventional wars – only hybrid ones. Hybrid wars are fought at varying intensities and scales, depending on the “means” available, the creativity of “ways” imagined, and the “ends” desired by the adversary. As the resources required to employ, and the destruction of lethal means increases, the more likely conflict will press “ways” horizontally into multiple domains and dimensions. While conflict in multiple domains is likely, large-scale multi-domain operations remain less likely between two great powers due to the conventional material costs and the slippery slope toward nuclear weapon use. If LSCO does occur, the likelihood of fighting through a CBRN environment is high.

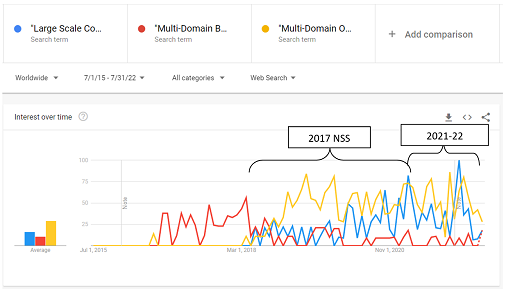

Panic at the LSCO

Yet in the Army today, what is old is new again. LSCO harkens back to the Army’s historical victories and provides a clearer purpose than “small wars” or counterinsurgency, making it particularly palatable to Army culture. However, the Army’s operational concept is Multi-Domain Operations (MDO), not LSCO. While MDO acknowledges the very real possibility of LSCO, it does not forecast LSCO’s inevitability over other forms of conflict, competition, or even cooperation. So, while all LSCO is likely a Multi-Domain Operation, not all MDO is LSCO. Assuming that great powers will only fight great wars can lead to death by a thousand cuts while holding a tourniquet. Instead, our approach to the future must include the full spectrum of operations.

Yet in the Army today, what is old is new again. LSCO harkens back to the Army’s historical victories and provides a clearer purpose than “small wars” or counterinsurgency, making it particularly palatable to Army culture. However, the Army’s operational concept is Multi-Domain Operations (MDO), not LSCO. While MDO acknowledges the very real possibility of LSCO, it does not forecast LSCO’s inevitability over other forms of conflict, competition, or even cooperation. So, while all LSCO is likely a Multi-Domain Operation, not all MDO is LSCO. Assuming that great powers will only fight great wars can lead to death by a thousand cuts while holding a tourniquet. Instead, our approach to the future must include the full spectrum of operations.

Ramifications for the Future

To be clear, I am not saying that developing LSCO capabilities is wrong. But like Kagan (2020), I am saying we must ensure that our refocus precludes an  overcorrection. For example, the current Russo-Ukraine War is cited as a case for the return of LSCO. Yet from a Great Power perspective, it is a proxy war. Ukraine gave up its nuclear weapons and is now a target by a state that is bound by treaty to guarantee its security. Operationally, we may learn LSCO lessons from this war, but strategically the lessons are different.

overcorrection. For example, the current Russo-Ukraine War is cited as a case for the return of LSCO. Yet from a Great Power perspective, it is a proxy war. Ukraine gave up its nuclear weapons and is now a target by a state that is bound by treaty to guarantee its security. Operationally, we may learn LSCO lessons from this war, but strategically the lessons are different.

The Army of the future must be able to generate deterrence by denial and by punishment in both LSCO and Non-LSCO conditions, across multiple domains, and diverse geography. Deterrence by denial requires both capability and will that make it infeasible for an adversary to succeed, while punishment requires severe penalties (Mazarr 2018). If the Army attempts to leave unconventional war behind, non-denied space is created which adversaries could exploit, likely through proxies. Conventional responses are often unsuitable to such threats, providing adversaries with an asymmetric advantage resistant to deterrence by conventional punishment. To mitigate outcomes such as these, tailored forces are required in the unconventional space (Crombe, Ferenzi, and Jones 2021). Ensuring balance across domains and DIME is foundational to integrated deterrence (McInnis 2022).

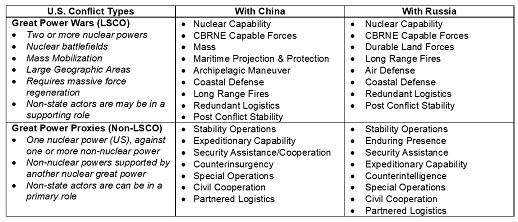

Avoiding historical biases toward conventional capability and not relying on Cold War definitions of deterrence requires vigilance. As designers of the future endure the machinations of modernization, they should employ tools to maintain balance. For example, the matrix in Table 1 (below) looks at geographic threats, compared to both LSCO and non-LSCO conflict types. Experimentation, wargaming, operations research, historical review, or other methods help determine the form of capabilities required by the framework. In turn, force designs can be tailored and judged appropriately across all three components. Tools like these should be employed in the developmental processes.

Conclusion

The Army may learn incorrect historical lessons if we assume great powers will fight great wars. While many great powers fought each other directly, they also fought small adversaries and used proxies. Russia is learning today the costs of modern conventional war are so high it is difficult to justify its use. Since World War II, no two nuclear-armed countries directly went to war with each other. A focus on the “most dangerous” form of war (LSCO) is appropriate to create a credible deterrent, but cannot wholly replace other capabilities required for MDO. Strategically, without credible non-LSCO capabilities, deterrence by denial is not truly possible.

If you enjoyed this post, check out the following related content:

Insights from Ukraine on the Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Warfare

China’s PLA Modernization through the DOTMLPF-P Lens by Dr. Jacob Barton

Would You Like to Play a Game? Wargaming as a Learning Experience and Key Assumptions Check and “No Option is Excluded” — Using Wargaming to Envision a Chinese Assault on Taiwan, by Ian Sullivan

Other People’s Wars: The US Military and the Challenge of Learning from Foreign Conflicts and associated podcast, with Brent L. Sterling

Then and Now: Using the Past to Secure the Future and associated podcast, with Warrant Officer Class 2 Paul Barnes, British Army,

Four Models of the Post-COVID World

The Future Operational Environment: The Four Worlds of 2035-2050

The Army’s Next Failed War: Large Scale Combat Operations, by MAJ Anthony Joyce

Disrupting the “Chinese Dream” – Eight Insights on how to win the Competition with China

Hybrid Threats and Liminal Warfare and associated podcast, with proclaimed Mad Scientist Dr. David Kilcullen

Non-Kinetic War, by COL Steve Banach (USA-Ret.)

Alternate Futures 2050: A Collection of Fictional Wartime Vignettes, by LTC Steve Speece

The Battle of Rioni River Valley: A Story of Future Warfare in 2030, by MAJ James P. Micciche

The Outsized Fear of Small Nuclear Threats, by proclaimed Mad Scientist Dr. James Giordano and Bob Williams

About the Author: Nathan Colvin is a U.S. Army Strategist recently selected for Colonel and the U.S. Army War College Fellowship in Public Policy at the College of William and Mary. He holds a Graduate Certificate in Modeling and Simulations from Old Dominion University, where he is also completing his last semester of coursework toward a Ph.D. in International Studies as an I/ITSEC Leonard P. Gollobin Scholar. He earned master’s degrees in Aeronautics and Space Studies (Embry-Riddle University), Administration (Central Michigan University), and Military Theater Operations (School of Advanced Military Studies). He has deployed to Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Latvia as an aviator, operational planner, and strategist. He is currently participating in the HillVets LEAD program where he will chair a panel on US-Ukrainian Veteran cooperation in employment and entrepreneurship.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

“the probability and severity of loss linked to hazards. Risk, uncertainty, and chance are inherent in all military operations. When commanders accept risk, they create opportunities to seize, retain, and exploit operational initiative and achieve decisive results. The willingness to incur risk is often the key to exposing enemy weaknesses that an enemy considers beyond friendly reach. Understanding risk requires accurate running estimates and valid assumptions. Embracing risk as opportunity requires situational awareness and imagination, as well as audacity. Successful commanders assess and mitigate risk continuously throughout the operations process.”

“the probability and severity of loss linked to hazards. Risk, uncertainty, and chance are inherent in all military operations. When commanders accept risk, they create opportunities to seize, retain, and exploit operational initiative and achieve decisive results. The willingness to incur risk is often the key to exposing enemy weaknesses that an enemy considers beyond friendly reach. Understanding risk requires accurate running estimates and valid assumptions. Embracing risk as opportunity requires situational awareness and imagination, as well as audacity. Successful commanders assess and mitigate risk continuously throughout the operations process.”

General Robert Brown (USA-Ret.) is an experienced commander who has led at every level, from platoon through Army Service Component Command. Serving as Commanding General of U.S. Army Pacific, General Brown led the Army’s largest service component command responsible for 106,000 Soldiers across the Indo-Pacific Region before his September 2019 retirement.

General Robert Brown (USA-Ret.) is an experienced commander who has led at every level, from platoon through Army Service Component Command. Serving as Commanding General of U.S. Army Pacific, General Brown led the Army’s largest service component command responsible for 106,000 Soldiers across the Indo-Pacific Region before his September 2019 retirement. General Brown holds a Bachelor of Science from the United States Military Academy, a Master of Education from the University of Virginia, and a Master of Science in National Security and Strategic Studies (Distinguished Graduate) from the National Defense University.

General Brown holds a Bachelor of Science from the United States Military Academy, a Master of Education from the University of Virginia, and a Master of Science in National Security and Strategic Studies (Distinguished Graduate) from the National Defense University. have become heavily fortified in the post-9/11 environment, making it more difficult to reach that

have become heavily fortified in the post-9/11 environment, making it more difficult to reach that

development will need to produce individuals who thrive in ambiguity and chaos and the next generation of Soldiers must be

development will need to produce individuals who thrive in ambiguity and chaos and the next generation of Soldiers must be

of the U.S, Merchant Fleet — none of the six resupply ships sent to Guam made it. While both sides forswore the first use of nuclear weapons, industrial scale warfare had returned to our world and our world was fundamentally changed.

of the U.S, Merchant Fleet — none of the six resupply ships sent to Guam made it. While both sides forswore the first use of nuclear weapons, industrial scale warfare had returned to our world and our world was fundamentally changed. While CCP troops stormed into Korea and

While CCP troops stormed into Korea and  the looming deaths of tens of millions of their citizens as an opportunity to reset Chinese society, a second

the looming deaths of tens of millions of their citizens as an opportunity to reset Chinese society, a second

Our adversaries continue to probe, watch, and learn from us, driven to rapidly innovate in their quest for asymmetric advantage. LTC Gomez explores one such advantage at the nexus of online gaming, where savvy adversaries can “conduct multi-domain, synchronized operations across multiple geospatial regions…. operating as independent self-sustained and distributed joint teams, using real-time culturally neutral comms.” Read on to learn how Decentralized Autonomous Organizations could converge the power and reach of gaming, the mass of like-minded “virtual nations” of individuals, and nefarious tactics like “Deep-Snapping,” “Spot-Blowing,” “Husking,” and Swatting to out-compete and out-influence the greatest global military power — “you have been warned!”]

Our adversaries continue to probe, watch, and learn from us, driven to rapidly innovate in their quest for asymmetric advantage. LTC Gomez explores one such advantage at the nexus of online gaming, where savvy adversaries can “conduct multi-domain, synchronized operations across multiple geospatial regions…. operating as independent self-sustained and distributed joint teams, using real-time culturally neutral comms.” Read on to learn how Decentralized Autonomous Organizations could converge the power and reach of gaming, the mass of like-minded “virtual nations” of individuals, and nefarious tactics like “Deep-Snapping,” “Spot-Blowing,” “Husking,” and Swatting to out-compete and out-influence the greatest global military power — “you have been warned!”] He watched as the blue and red lights of police cars swept across his leather couch and pictures of his wife and daughters. He listened as armed men trounced through his suburban home, resting in a subdivision cul-de-sac just outside Alexandria. The officers called to each other, their conversation accented by doors being kicked open.

He watched as the blue and red lights of police cars swept across his leather couch and pictures of his wife and daughters. He listened as armed men trounced through his suburban home, resting in a subdivision cul-de-sac just outside Alexandria. The officers called to each other, their conversation accented by doors being kicked open. However, before Jamil could voice his anger, the outrage, the mortal danger they could have put his family in, the lead officer interrupted his thoughts, “Sir, I am sorry, but,” he paused, “We believe you were swatted.”

However, before Jamil could voice his anger, the outrage, the mortal danger they could have put his family in, the lead officer interrupted his thoughts, “Sir, I am sorry, but,” he paused, “We believe you were swatted.” intelligence MS PowerPoint presentation, seventeen white papers on transnational organizations, a

intelligence MS PowerPoint presentation, seventeen white papers on transnational organizations, a  Rodriguez nodded, her eyebrows scrunching together along with her nose.

Rodriguez nodded, her eyebrows scrunching together along with her nose.

zombies, and managing their army. After reaching level 10, players would be thrust into a random clan to continue their journey to become Clan Master of their numbered region. These clans and regions, however, were not geo-specific. Players from any country with Wi-Fi or satellite service would join together and conduct operations across SCL‘s different gameplay modes. SCL also featured micro-transactions so paying players could jump ahead of their peers by substituting money for speed-ups and resources.

zombies, and managing their army. After reaching level 10, players would be thrust into a random clan to continue their journey to become Clan Master of their numbered region. These clans and regions, however, were not geo-specific. Players from any country with Wi-Fi or satellite service would join together and conduct operations across SCL‘s different gameplay modes. SCL also featured micro-transactions so paying players could jump ahead of their peers by substituting money for speed-ups and resources. of up to 80 players at a time across multiple time zones and countries. SCL had an auto-translate chat feature that could enable communication across one hundred languages. The LAST Clan had members from Korea, China, the USA, Turkey, Russia, and Brazil, to name a few. Additionally, in WAR, the clans had to manage their alliances, map out the regions of opposing clans, and manage their clan bonus resources to support their invasion force.

of up to 80 players at a time across multiple time zones and countries. SCL had an auto-translate chat feature that could enable communication across one hundred languages. The LAST Clan had members from Korea, China, the USA, Turkey, Russia, and Brazil, to name a few. Additionally, in WAR, the clans had to manage their alliances, map out the regions of opposing clans, and manage their clan bonus resources to support their invasion force. “What LAST is doing, is using SCL, to learn how to conduct multi-domain, synchronized operations across multiple geospatial regions! They are operating as independent self-sustained and distributed joint teams, using real-time culturally neutral comms,” he finished, emphatically drawing arrows connecting all of the shapes.

“What LAST is doing, is using SCL, to learn how to conduct multi-domain, synchronized operations across multiple geospatial regions! They are operating as independent self-sustained and distributed joint teams, using real-time culturally neutral comms,” he finished, emphatically drawing arrows connecting all of the shapes. LAST engaged in blackmail Deep-Snapping (manipulating accessed home camera video with

LAST engaged in blackmail Deep-Snapping (manipulating accessed home camera video with  Rodriguez felt like a broken record. She tried to explain to her leaders how our adversaries would use the convergence of emergent technologies to their advantage, but to no avail.

Rodriguez felt like a broken record. She tried to explain to her leaders how our adversaries would use the convergence of emergent technologies to their advantage, but to no avail.  “Good Afternoon, Sarah; my name is Jade. LAST has been watching your little work there in Constantinople, and LAST is not pleased. Discontinue your operations now, or face the consequences,” she whispered. “You have been warned.”

“Good Afternoon, Sarah; my name is Jade. LAST has been watching your little work there in Constantinople, and LAST is not pleased. Discontinue your operations now, or face the consequences,” she whispered. “You have been warned.” mercury off the satellite phone inside with his sleeve and plugged in a dilithium battery. The phone vibrated and turned green, showing it had achieved signal.

mercury off the satellite phone inside with his sleeve and plugged in a dilithium battery. The phone vibrated and turned green, showing it had achieved signal.