[Editor’s Note: The U.S. Army’s capstone unclassified document on the Operational Environment (OE) states:

“Russia can be considered our “pacing threat,” and will be our most capable potential foe for at least the first half of the Era of Accelerated Human Progress [now through 2035]. It will remain a key strategic competitor through the Era of Contested Equality [2035 through 2050].” TRADOC Pamphlet (TP) 525-92, The Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Warfare, p. 12.

In today’s companion piece to the previously published China: Our Emergent Pacing Threat, the Mad Scientist Laboratory reviews what we’ve learned about Russia in an anthology of insights gleaned from previous posts regarding our current pacing threat — this is a far more sophisticated strategic competitor than your Dad’s (or Mom’s!) Soviet Union — Enjoy!].

The dichotomy of war and peace is no longer a useful construct for thinking about national security or the development of land force capabilities. There are no longer defined transitions from peace to war and competition to conflict. This state of simultaneous competition and conflict is continuous and dynamic, but not necessarily cyclical. Russia will seek to achieve its national interests short of conflict and will use a range of actions from cyber to kinetic against unmanned systems walking up to the line of a short or protracted armed conflict.

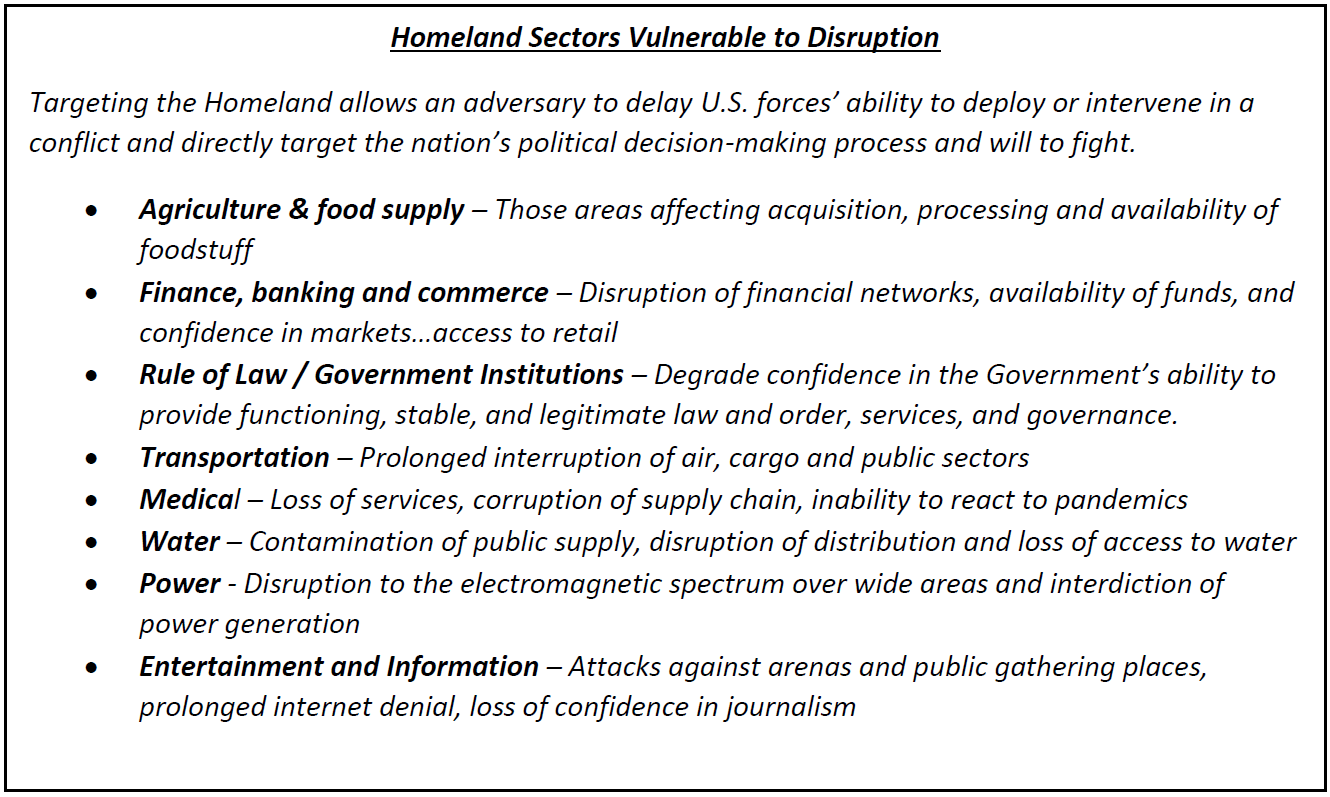

1. Hemispheric Competition and Conflict: Over the last twenty years, Russia has been viewed as regional competitor in Eurasia, seeking to undermine and fracture traditional Western institutions, democracies, and alliances. It is now transitioning into a hemispheric threat with a primary focus on challenging the  U.S. Army all the way from our home station installations (i.e., the Strategic Support Area) to the Close Area fight. We can expect cyber attacks against critical infrastructure, the use of advanced information warfare such as deepfakes targeting units and families, and the possibility of small scale kinetic attacks during what were once uncontested administrative actions of deployment. There is no institutional memory for this type of threat and adding time and required speed for deployment is not enough to exercise Multi-Domain Operations.

U.S. Army all the way from our home station installations (i.e., the Strategic Support Area) to the Close Area fight. We can expect cyber attacks against critical infrastructure, the use of advanced information warfare such as deepfakes targeting units and families, and the possibility of small scale kinetic attacks during what were once uncontested administrative actions of deployment. There is no institutional memory for this type of threat and adding time and required speed for deployment is not enough to exercise Multi-Domain Operations.

See: Blurring Lines Between Competition and Conflict

2. Cyber Operations: Russia has already employed tactics designed to exploit vulnerabilities arising from Soldier connectivity. In the ongoing Ukrainian conflict, for example,  Russian cyber operations coordinated attacks against Ukrainian artillery, in just one case of a “really effective integration of all these [cyber] capabilities with kinetic measures.” By sending spoofed text messages to Ukrainian soldiers informing them that their support battalion has retreated, their bank account has been exhausted, or that they are simply surrounded and have been abandoned, they trigger personal communications, enabling the Russians to fix and target Ukrainian positions. Taking it one step further, they have even sent false messages to the families of soldiers informing them that their loved one was killed in action. This sets off a chain of events where the family member will immediately call or text the soldier, followed

Russian cyber operations coordinated attacks against Ukrainian artillery, in just one case of a “really effective integration of all these [cyber] capabilities with kinetic measures.” By sending spoofed text messages to Ukrainian soldiers informing them that their support battalion has retreated, their bank account has been exhausted, or that they are simply surrounded and have been abandoned, they trigger personal communications, enabling the Russians to fix and target Ukrainian positions. Taking it one step further, they have even sent false messages to the families of soldiers informing them that their loved one was killed in action. This sets off a chain of events where the family member will immediately call or text the soldier, followed  by another spoofed message to the original phone. With a high number of messages to enough targets, an artillery strike is called in on the area where an excess of cellphone usage has been detected. To translate into plain English, Russia has successfully combined traditional weapons of land warfare (such as artillery) with the new potential of cyber warfare.

by another spoofed message to the original phone. With a high number of messages to enough targets, an artillery strike is called in on the area where an excess of cellphone usage has been detected. To translate into plain English, Russia has successfully combined traditional weapons of land warfare (such as artillery) with the new potential of cyber warfare.

See: Nowhere to Hide: Information Exploitation and Sanitization and Hal Wilson‘s Britain, Budgets, and the Future of Warfare.

3. Influence Operations: Russia seeks to shape public opinion and influence decisions through targeted information operations (IO) campaigns, often relying on weaponized social media. Russia recognizes the importance of AI, particularly to match and overtake the superior military capabilities that the United States  and its allies have held for the past several decades. Highlighting this importance, Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2017 stated that “whoever becomes the leader in this sphere will become the ruler of the world.” AI-guided IO tools can empathize with an audience to say anything, in any way needed, to change the perceptions that drive those physical weapons. Future IO systems will be able to individually monitor and affect tens of thousands of people at once.

and its allies have held for the past several decades. Highlighting this importance, Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2017 stated that “whoever becomes the leader in this sphere will become the ruler of the world.” AI-guided IO tools can empathize with an audience to say anything, in any way needed, to change the perceptions that drive those physical weapons. Future IO systems will be able to individually monitor and affect tens of thousands of people at once.

Russian bot armies continue to make headlines in executing IO. The New York Times maintains about a dozen Twitter feeds and produces around 300 tweets a day, but Russia’s Internet Research Agency (IRA) regularly puts out 25,000 tweets in the same twenty-four hours. The IRA’s bots are really just low-tech curators; they collect, interpret, and display desired information to promote the Kremlin’s narratives.

Next-generation bot armies will employ far faster computing techniques and profit from an order of magnitude greater network speed when 5G services are fielded. If “Repetition is a key tenet of IO execution,” then this machine gun-like ability to fire information at an audience will, with empathetic precision and custom content, provide the means to change a decisive audience’s very reality. No breakthrough science is needed, no bureaucratic project office required. These pieces are already there, waiting for an adversary to put them together.

Next-generation bot armies will employ far faster computing techniques and profit from an order of magnitude greater network speed when 5G services are fielded. If “Repetition is a key tenet of IO execution,” then this machine gun-like ability to fire information at an audience will, with empathetic precision and custom content, provide the means to change a decisive audience’s very reality. No breakthrough science is needed, no bureaucratic project office required. These pieces are already there, waiting for an adversary to put them together.

One future vignette posits Russia’s GRU (Military Intelligence) employing AI Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to create fake persona injects that mimic select U.S. Active Army, ARNG, and USAR commanders making disparaging statements about their confidence in our allies’ forces, the legitimacy of the mission, and their faith in our political leadership. Sowing these injects across unit social media accounts, Russian Information Warfare specialists could seed doubt and erode trust in the chain of command amongst a percentage of susceptible Soldiers, creating further friction.

One future vignette posits Russia’s GRU (Military Intelligence) employing AI Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to create fake persona injects that mimic select U.S. Active Army, ARNG, and USAR commanders making disparaging statements about their confidence in our allies’ forces, the legitimacy of the mission, and their faith in our political leadership. Sowing these injects across unit social media accounts, Russian Information Warfare specialists could seed doubt and erode trust in the chain of command amongst a percentage of susceptible Soldiers, creating further friction.

See: Weaponized Information: One Possible Vignette, Own the Night, The Death of Authenticity: New Era Information Warfare, and MAJ Chris Telley‘s Influence at Machine Speed: The Coming of AI-Powered Propaganda

4. Isolation: Russia seeks to cocoon itself from retaliatory IO and Cyber Operations. At the October 2017 meeting of the Security Council, “the FSB [Federal Security Service] asked the government to develop an independent  ‘Internet’ infrastructure for BRICS nations [Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa], which would continue to work in the event the global Internet malfunctions.” Security Council members argued the Internet’s threat to national security is due to:

‘Internet’ infrastructure for BRICS nations [Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa], which would continue to work in the event the global Internet malfunctions.” Security Council members argued the Internet’s threat to national security is due to:

“… the increased capabilities of Western nations to conduct offensive operations in the informational space as well as the increased readiness to exercise these capabilities.”

Having its own root servers would make Russia independent of monitors like the International Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) and protect the country in the event of “outages or deliberate interference.” “Putin sees [the] Internet as [a] CIA tool.”

See: Dr. Mica Hall‘s The Cryptoruble as a Stepping Stone to Digital Sovereignty and Howard R. Simkin‘s Splinternets

5. Battlefield Automation: Given the rapid proliferation of unmanned and autonomous technology, we are already in the midst of a new arms race. Russia’s  Syria experience — and monitoring the U.S. use of unmanned systems for the past two decades — convinced the Ministry of Defense (MOD) that its forces need more expanded unmanned combat capabilities to augment existing Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) systems that allow Russian forces to observe the battlefield in real time.

Syria experience — and monitoring the U.S. use of unmanned systems for the past two decades — convinced the Ministry of Defense (MOD) that its forces need more expanded unmanned combat capabilities to augment existing Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) systems that allow Russian forces to observe the battlefield in real time.

The next decade will see Russia complete the testing and evaluation of an entire lineup of combat drones that were in different stages of development over the previous decade. They include the heavy Ohotnik combat UAV (UCAV); mid-range Orion that was tested in Syria; Russian-made Forpost, a UAV that was originally assembled via Israeli license; mid-range Korsar; and long-range Altius that was billed as Russia’s equivalent to the American Global Hawk drone. All of these UAVs are several years away from potential acquisition by armed forces, with some going through factory tests, while others graduating to military testing and evaluation. These UAVs will have a range from over a hundred to possibly thousands of kilometers, depending on the model, and will be able to carry weapons for a diverse set of missions.

Russian ground forces have also been testing a full lineup of Unmanned Ground Vehicles (UGVs), from small to tank-sized vehicles armed with machine guns, cannon, grenade launchers, and sensors. The MOD is conceptualizing how such UGVs could be used in a range of combat scenarios, including urban combat.  However, in a candid admission, Andrei P. Anisimov, Senior Research Officer at the 3rd Central Research Institute of the Ministry of Defense, reported on the Uran-9’s critical combat deficiencies during the 10th All-Russian Scientific Conference entitled “Actual Problems of Defense and Security,” held in April 2018. The Uran-9 is a test bed system and much has to take place before it could be successfully integrated into current Russian concept of operations. What is key is that it has been tested in a combat environment and the Russian military and defense establishment are incorporating lessons learned into next-gen systems. We could expect more eye-opening lessons learned from its’ and other UGVs potential deployment in combat.

However, in a candid admission, Andrei P. Anisimov, Senior Research Officer at the 3rd Central Research Institute of the Ministry of Defense, reported on the Uran-9’s critical combat deficiencies during the 10th All-Russian Scientific Conference entitled “Actual Problems of Defense and Security,” held in April 2018. The Uran-9 is a test bed system and much has to take place before it could be successfully integrated into current Russian concept of operations. What is key is that it has been tested in a combat environment and the Russian military and defense establishment are incorporating lessons learned into next-gen systems. We could expect more eye-opening lessons learned from its’ and other UGVs potential deployment in combat.

Another significant trend is the gradual shift from manual control over unmanned systems to a fully autonomous mode, perhaps powered by a limited Artificial  Intelligence (AI) program. The Russian MOD has already communicated its desire to have unmanned military systems operate autonomously in a fast-paced and fast-changing combat environment. While the actual technical solution for this autonomy may evade Russian designers in this decade due to its complexity, the MOD will nonetheless push its developers for near-term results that may perhaps grant such fighting vehicles limited semi-autonomous status. The MOD would also like this AI capability be able to direct swarms of air, land, and sea-based unmanned and autonomous systems.

Intelligence (AI) program. The Russian MOD has already communicated its desire to have unmanned military systems operate autonomously in a fast-paced and fast-changing combat environment. While the actual technical solution for this autonomy may evade Russian designers in this decade due to its complexity, the MOD will nonetheless push its developers for near-term results that may perhaps grant such fighting vehicles limited semi-autonomous status. The MOD would also like this AI capability be able to direct swarms of air, land, and sea-based unmanned and autonomous systems.

The Russians have been public with both their statements about new technology being tested and evaluated, and with possible use of such weapons in current and future conflicts. There should be no strategic or tactical surprise when military robotics are finally encountered in future combat.

See proclaimed Mad Scientist Sam Bendett‘s Major Trends in Russian Military Unmanned Systems Development for the Next Decade, Autonomous Robotic Systems in the Russian Ground Forces, and Russian Ground Battlefield Robots: A Candid Evaluation and Ways Forward,

6. Innovation: Russia has developed a military innovation center — Era Military Innovation Technopark — near the city of Anapa (Krasnodar Region) on the northern coast of the Black Sea. Touted as “A Militarized Silicon Valley in Russia,” the facility will be co-located with representatives of Russia’s top arms manufacturers which will “facilitate the growth of the efficiency of interaction among educational, industrial, and research organizations.” By bringing together the best and brightest in the field of “breakthrough technology,” the Russian leadership hopes to see “development in such fields as nanotechnology and biotech, information and telecommunications technology, and data protection.”

That said, while Russian scientists have often been at the forefront of technological innovations, the country’s poor legal system prevents these discoveries from ever bearing fruit. Stifling bureaucracy and a broken legal system prevent Russian scientists and innovators from profiting from their discoveries. The jury is still out as to whether Russia’s Era Military Innovation Technopark can deliver real innovation.

See: Ray Finch‘s “The Tenth Man” — Russia’s Era Military Innovation Technopark

Russia’s embrace of these and other disruptive technologies and the way in which they adopt hybrid strategies that challenge traditional symmetric advantages and conventional ways of war increases their ability to challenge U.S. forces across multiple domains. As an authoritarian regime, Russia is able to more easily ensure unity of effort and a whole-of-government focus over the Western democracies. It will continue to seek out and exploit fractures and gaps in the U.S. and its allies’ decision-making, governance, and policy.

Russia’s embrace of these and other disruptive technologies and the way in which they adopt hybrid strategies that challenge traditional symmetric advantages and conventional ways of war increases their ability to challenge U.S. forces across multiple domains. As an authoritarian regime, Russia is able to more easily ensure unity of effort and a whole-of-government focus over the Western democracies. It will continue to seek out and exploit fractures and gaps in the U.S. and its allies’ decision-making, governance, and policy.

If you enjoyed this post, check out these other Mad Scientist Laboratory anthologies:

-

- The Information Environment: Competition and Conflict anthology, a collection of previously published blog posts that serves as a primer on this topic and examines the convergence of technologies that facilitates information weaponization.

- FY18 Mad Scientist Laboratory Anthology, serves up “the best of” futures oriented assessments published during the MadSciBlog’s first year.

mirror imaging. The Mad Scientist Laboratory offers it as a platform for the contrarians in our network to share their alternative perspectives and analyses regarding the Operational Environment (OE). We continue our series of “Tenth Man” posts examining the foundational assumptions of

mirror imaging. The Mad Scientist Laboratory offers it as a platform for the contrarians in our network to share their alternative perspectives and analyses regarding the Operational Environment (OE). We continue our series of “Tenth Man” posts examining the foundational assumptions of The character of warfare will change in the future OE as it inexorably has since the advent of flint hand axes; iron blades; stirrups; longbows; gunpowder; breech loading, rifled, and automatic guns; mechanized armor; precision-guided munitions; and the Internet of Things. Speed, automation, extended ranges,

The character of warfare will change in the future OE as it inexorably has since the advent of flint hand axes; iron blades; stirrups; longbows; gunpowder; breech loading, rifled, and automatic guns; mechanized armor; precision-guided munitions; and the Internet of Things. Speed, automation, extended ranges,  broad and narrow weapons effects, and increasingly integrated multi-domain conduct, in addition to the complexity of the terrain and social structures in which it occurs, will make mid Twenty-first Century warfare both familiar and utterly alien.

broad and narrow weapons effects, and increasingly integrated multi-domain conduct, in addition to the complexity of the terrain and social structures in which it occurs, will make mid Twenty-first Century warfare both familiar and utterly alien. assumes that humans will remain central to the rationale for war and its most essential elements of execution. The nature of war has remained relatively constant from Thucydides through Clausewitz, and forward to the present. War is still waged because of fear, honor, and interest, and remains an expression of politics by other means. While machines are becoming ever more prevalent across the battlefield – C5ISR, maneuver, and logistics – we cling to the belief that parties will still go to war over human interests; that war will be decided, executed, and controlled by humans.

assumes that humans will remain central to the rationale for war and its most essential elements of execution. The nature of war has remained relatively constant from Thucydides through Clausewitz, and forward to the present. War is still waged because of fear, honor, and interest, and remains an expression of politics by other means. While machines are becoming ever more prevalent across the battlefield – C5ISR, maneuver, and logistics – we cling to the belief that parties will still go to war over human interests; that war will be decided, executed, and controlled by humans. Imagine that a machine recognizes a strategic opportunity or impetus to engage a nation-state actor that is conventionally (read that humanly) viewed as weak or in a presumed disadvantaged state. The machine launches offensive operations to achieve a favorable outcome or objective that it deemed too advantageous to pass up.

Imagine that a machine recognizes a strategic opportunity or impetus to engage a nation-state actor that is conventionally (read that humanly) viewed as weak or in a presumed disadvantaged state. The machine launches offensive operations to achieve a favorable outcome or objective that it deemed too advantageous to pass up. influence may not be conducive to victory. Victory may be simply a calculated or algorithmic outcome that causes an adversary’s machine to decide their own victory is unattainable.

influence may not be conducive to victory. Victory may be simply a calculated or algorithmic outcome that causes an adversary’s machine to decide their own victory is unattainable. – How much and how should the Army recruit and cultivate human talent if war is no longer human-centric?

– How much and how should the Army recruit and cultivate human talent if war is no longer human-centric? – Should the U.S. military divest from platforms and materiel solutions (hardware) and re-focus on becoming algorithmically and digitally-centric (software)?

– Should the U.S. military divest from platforms and materiel solutions (hardware) and re-focus on becoming algorithmically and digitally-centric (software)? – Technology advances to the point of near or actual machine sentience, with commensurate machine speed accelerating the potential for escalated competition and armed conflict beyond transparency and human comprehension.

– Technology advances to the point of near or actual machine sentience, with commensurate machine speed accelerating the potential for escalated competition and armed conflict beyond transparency and human comprehension. – Smaller, less-capable states or actors begin achieving surprising or unexpected victories in warfare.

– Smaller, less-capable states or actors begin achieving surprising or unexpected victories in warfare.

Post: In a not too distant future, 20th of August 2034, a peer adversary’s first strategic moves are the targeted killings of less than twenty individuals as they go about their daily lives: watching a 3-D printer making a protein sandwich at a breakfast restaurant; stepping out from the downtown Chicago monorail; or taking a taste of a poison-filled retro Jolt Cola. In the

Post: In a not too distant future, 20th of August 2034, a peer adversary’s first strategic moves are the targeted killings of less than twenty individuals as they go about their daily lives: watching a 3-D printer making a protein sandwich at a breakfast restaurant; stepping out from the downtown Chicago monorail; or taking a taste of a poison-filled retro Jolt Cola. In the The ability to apply is a far greater asset than the technology itself. Cyber and card games have one thing in common, the order you play your cards matters. In cyber, the tools are publicly available, anyone can download them from the Internet and use them, but the weaponization of the tools occurs when used by someone who understands how to play the tools in an optimal order. These minds are different because they see an opportunity to exploit in a digital fog of war where others don’t or can’t see it. They address problems unburdened by traditional thinking, in new innovative ways, maximizing the dual-purpose of digital tools, and can create tangible cyber effects.

The ability to apply is a far greater asset than the technology itself. Cyber and card games have one thing in common, the order you play your cards matters. In cyber, the tools are publicly available, anyone can download them from the Internet and use them, but the weaponization of the tools occurs when used by someone who understands how to play the tools in an optimal order. These minds are different because they see an opportunity to exploit in a digital fog of war where others don’t or can’t see it. They address problems unburdened by traditional thinking, in new innovative ways, maximizing the dual-purpose of digital tools, and can create tangible cyber effects. It is the Applicable Intelligence (AI) that creates the procedures, the application of tools, and turns simple digital software in sets or combinations as a convergence to digitally lethal weapons. This AI is the intelligence to mix, match, tweak, and arrange dual purpose software. In 2034, it is as if you had the supernatural ability to create a thermonuclear bomb from what you can find at Kroger or Albertson.

It is the Applicable Intelligence (AI) that creates the procedures, the application of tools, and turns simple digital software in sets or combinations as a convergence to digitally lethal weapons. This AI is the intelligence to mix, match, tweak, and arrange dual purpose software. In 2034, it is as if you had the supernatural ability to create a thermonuclear bomb from what you can find at Kroger or Albertson. Sadly we missed it; we didn’t see it. We never left the 20th century. Our adversary saw it clearly and at the dawn of conflict killed off the weaponized minds, without discretion, and with no concern for international law or morality.

Sadly we missed it; we didn’t see it. We never left the 20th century. Our adversary saw it clearly and at the dawn of conflict killed off the weaponized minds, without discretion, and with no concern for international law or morality.

The nature of war, which has remained relatively constant from Thucydides, through Clausewitz, through the Cold War, and on into the present, certainly remains constant through the Era of Accelerated Human Progress

The nature of war, which has remained relatively constant from Thucydides, through Clausewitz, through the Cold War, and on into the present, certainly remains constant through the Era of Accelerated Human Progress  (i.e., now through 2035). War is still waged because of fear, honor, and interest, and remains an expression of politics by other means. However, as we move into the Era of Contested Equality (i.e., 2035-2050), the character of warfare has changed in several key areas:

(i.e., now through 2035). War is still waged because of fear, honor, and interest, and remains an expression of politics by other means. However, as we move into the Era of Contested Equality (i.e., 2035-2050), the character of warfare has changed in several key areas: • The Moral and Cognitive Dimensions are Ascendant.

• The Moral and Cognitive Dimensions are Ascendant.  • Integration across Diplomacy, Information, Military, and Economic (DIME).

• Integration across Diplomacy, Information, Military, and Economic (DIME).  • Limitations of Military Force.

• Limitations of Military Force.  • The Primacy of Information.

• The Primacy of Information.  • Expansion of the Battle Area.

• Expansion of the Battle Area.

• Ethics of Warfare Shift.

• Ethics of Warfare Shift.