[Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist Laboratory welcomes guest blogger LTC Jim Armstrong, a student at the Army War College, with his insightful and provocative submission calling on the Army to instill a culture of innovation across the force and putting “Futures” back into Army Futures Command, rather than focusing modernization efforts on our pacing threats. LTC Armstrong proposes three mechanisms — decoupling ideas from experience, pursuing the connection of ideas, and consolidating gains with innovation leadership and management — as a prescription for linking the attributes and value of innovation to the Army’s culture and exploiting areas of potential to create a holistic, force-wide approach to innovation. Read on!]

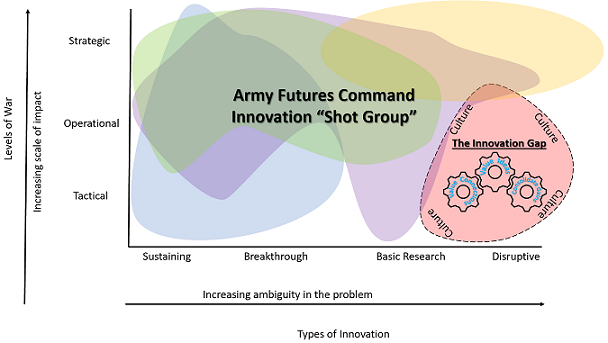

The current and future operational environment demands not just an Army that can innovate episodically and incrementally, but an Army with an innovative culture that is able to create, identify, and support all types of innovation at all levels of war. Senior Army leaders recognized this demand as demonstrated by the creation of Army Futures Command (AFC); however, without the ability to harness all types of innovation at all levels, neither AFC nor the operational force will fulfill their full potential necessary to achieve competitive advantage (see Figure 1).

Without a holistic approach, AFC is likely to act as a near-term modernization command. To reach full potential and allow AFC to focus on the strategic level, the Army needs to address the cultural obstacles which frustrate its ability to leverage innovation at the tactical level across the force to fill the gap in the innovation space.

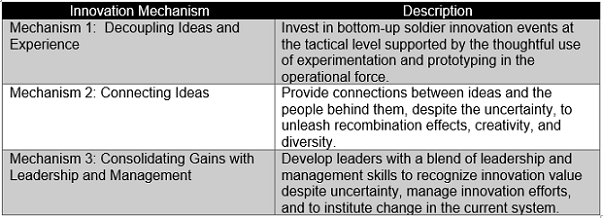

There are nascent Army tactical innovation efforts that are loosely connected to each other and a larger innovation ecosystem, including other Service innovation hubs, that show immense promise. However, if the Army is to better pursue innovation across the spectrum, they must create mechanisms designed to support a culture that embraces innovation at the tactical level. This tactical level innovation can achieve a more lasting impact as a complimentary effort to strategic level innovation at AFC. Three mechanisms which require Army investment to create this culture include decoupling ideas from experience, pursuing the connection of ideas, and consolidating gains with innovation leadership and management. Ultimately, if embraced, these mechanisms could allow the Army to keep the “Futures” in AFC, rather than focusing on keeping pace with our adversaries.

Mechanism 1: Decoupling Ideas and Experience

Experience is a necessary element of trusted military expertise. Given limited lateral entry, the Army is especially dependent on its members’ experience. Most importantly, the nature of the Army’s mission, to fight and win the nation’s wars, carries a risk unlike many other vocations. Given the risk of personal and collective survival, the Army necessarily and understandably emphasizes successful experiences. This emphasis exacerbates the innovator’s dilemma. The Army must provide avenues within its culture to value ideas based on their merits. The Army can better leverage their innovative potential by exploring capabilities and concepts from bottom-up and normalizing prototype and experimentation opportunities in the operational force.

The Army is involving Soldiers more in innovation efforts, but has yet to realize its full potential. For example, the Secretary of the Army codified the importance of Soldier “touch points” in his November 16, 2020 directive on “Achieving Persistent Modernization.” However, the bulk of current efforts are top-down ideas generated by a small portion of the force and given to Soldiers for feedback. While an important aspect of innovation, this approach does not harness the true power of those closest to problems at the tactical level. As a result of being closest to the problem, Soldiers understand the value proposition involved in potential solutions and failures, are more likely to see second and third order opportunities, and are more likely to develop novel approaches given their simple focus on solving the problem with less bureaucratic distractors or institutional bias. In addition to the likelihood of novel solutions, supporting Soldier innovation shows the Army values people, creates ownership, and propagates creative and critical thinking.

Supporting Soldier innovation requires operational units to make a habit of experimentation and prototyping. The Army has codified the idea of experimentation and prototyping to fail fast, fail early, fail cheap. However, these opportunities are too infrequent in the operational force at the tactical level. Operational units’ ability to conduct fruitful experiments and prototyping is an important part of problem solving, is critical to using valuable time wisely, and mitigates cost risk. Experimentation with prototypes allows Soldiers and the organization to learn by doing in a less expensive manner. Prototype efforts show dynamics of the problem not yet considered and highlight assumptions not yet recognized. Most importantly, working with prototypes is a critical facet of bottom-up idea development with disruptive results. Experimentation with prototype opportunities makes space for “creative serendipity,” where those immersed in the problem are likely to achieve breakthroughs because of their constant engagement; no one is more engaged with Army problems than Soldiers. The desire to learn inexpensively and use time wisely is a recognized advantage of experimentation and prototyping; however, the benefits of identifying solutions with new value propositions and learning about the problem more fully are not as recognized within the Army and must become a matter of course within the operational force.

Venues for crowdsourcing Soldier solutions provide an opportunity for leaders to hear from soldiers and drive competition amongst ideas. Shark Tank like events such as XVIII Airborne Corps’ Dragon Lair and other similar events are start points. These venues are a small piece of the soldier, bottom-up innovation process. These events and ideas must be nested as part of a guided innovation methodology. EAGLEWERX, Team Rainer at 2nd Battalion 75th

Venues for crowdsourcing Soldier solutions provide an opportunity for leaders to hear from soldiers and drive competition amongst ideas. Shark Tank like events such as XVIII Airborne Corps’ Dragon Lair and other similar events are start points. These venues are a small piece of the soldier, bottom-up innovation process. These events and ideas must be nested as part of a guided innovation methodology. EAGLEWERX, Team Rainer at 2nd Battalion 75th  Ranger Regiment, and AFWERX Spark Cells provide examples of forming an educated team capable of guiding a cycle of innovation. The team needs to understand agile product development and be able to guide soldiers with ideas through an iterative effort to reach a minimum viable solution. The right innovators mindset is critical for this team more so than degree specification, branch, or time served. Finally, if ideas are to become applied, they will need resources. While this article does not focus on resourcing challenges, further research on resourcing options need explored to provide the support necessary to complete the innovation cycle.

Ranger Regiment, and AFWERX Spark Cells provide examples of forming an educated team capable of guiding a cycle of innovation. The team needs to understand agile product development and be able to guide soldiers with ideas through an iterative effort to reach a minimum viable solution. The right innovators mindset is critical for this team more so than degree specification, branch, or time served. Finally, if ideas are to become applied, they will need resources. While this article does not focus on resourcing challenges, further research on resourcing options need explored to provide the support necessary to complete the innovation cycle.

Mechanism 2: The Connection of Ideas

Combining people and organizations with divergent viewpoints creates opportunities for merging resources, generating new ideas, and enabling unexpected results. The value of connecting ideas is overlooked because there is often not an immediate or direct relationship to tangible returns on investment before the pursuit begins. Keith Sawyer’s study of innovation using an approach he called “interaction analysis” concluded that no single person has the big idea, the complete meaning may not become clear until much later, and surprises emerge from the bottom-up. Williamson Murray and Allan Millett‘s comprehensive study of innovation in military history reinforces this same premise; there is often a complex confluence of people, timing, and organizations that produce new ideas whose paths were not apparent as the new idea was coming to fruition and are difficult to understand even with hindsight.

In addition to simply combining efforts, recombination of ideas can reconfigure old ideas in new ways and create momentum. Beyond the stitching together of the ideas, there is also power and momentum gained in the gathering of these networks themselves. Passionate problem solvers create a climate of their own akin to an insurgency where the network organizes itself and is governed by the problem solver ideology. These recombination effects and momentum are neither predictable nor tangible. Results are often unexpected. The energy and sense of community from these connections is not quantifiable; however, the unexpected is worth connecting.

Making connections of ideas and the people behind them based on common problems instead of common experience improves problem framing, cognitive approaches, and solution space. Connecting ideas is a way to expand discovery beyond natural institutional bias and prevent groupthink. Creating enough divergent viewpoints within the Army is not possible. The problems the Army must tackle are too complex and disparate for solutions to come from within the current system. External connections, like those happening at Army Applications Lab, must be a matter of course and linked to the soldiers closest to the problem in units at the tactical level. Partnerships like those at the 101st Airborne with Vanderbilt, Ranger Regiment with Georgia Tech, and 82nd Airborne with NC State are good examples, but the opportunities for these partnerships are underleveraged. Increasing operational unit involvement with programs like  National Security Innovation Network’s X-Force can help. Connections beyond the military increases the possibility of discovering something new and, especially in the Army, requires purposeful effort to achieve different viewpoints.

National Security Innovation Network’s X-Force can help. Connections beyond the military increases the possibility of discovering something new and, especially in the Army, requires purposeful effort to achieve different viewpoints.

The most concrete benefit of connecting ideas is the exponential increase in problem solvers. The Army has more than one million potential problem solvers and is underrating what the Army knows to be its most critical asset — people. However, the Army’s natural inclination to impose order through centralization and formal structure to gain efficiency and achieve unity of command in connecting these problem solvers will naturally crowd out tactical innovation. An informal ecosystem model for realizing innovation potential, though counter-cultural, is characterized by tailored idea hubs and platforms that assist innovators in connecting rather than a single structure providing direction to all. The Army must enable connection without providing a structure that stifles the conditions for innovation.

Current idea connection platforms in the Army innovation ecosystem are immature. While nascent, this is the area with most potential because of the pockets of excellence already happening in the force. The 75th Ranger Regiment has articulated this same problem and, as of early 2021, is pursuing an innovation marketplace and collaboration tool, “Go Innovate,” with promise. This tool not only connects innovators, but also uses software platforms to help with problem formulation and solution design. With the right leader involvement and resourcing, this tool could provide connections across an informal ecosystem within months.

Mechanism 3 Consolidating Gains with Leadership and Management

Consolidating gains is the most critical task leaders must accomplish over the next three to five years if the Army is to move beyond structural innovative solutions to a culture that supports continuous tactical innovation. In the Army’s leadership doctrine, there are two short paragraphs about innovation as a component within the Army leader attribute of intellect. Although under addressed, the espoused leader attributes and competencies in Army documents puts the Army in a better position to support tactical innovation  than these two paragraphs suggest. The Army’s mission command ideals are especially relevant if applied within the spirit of its creation. However, an overlooked aspect of tactical innovation that only leaders can address is the ability to consolidate gains.

than these two paragraphs suggest. The Army’s mission command ideals are especially relevant if applied within the spirit of its creation. However, an overlooked aspect of tactical innovation that only leaders can address is the ability to consolidate gains.

Rather than focusing on the immeasurable personal qualities for leaders to innovate, the Army needs leaders able to recognize innovative efforts, support the efforts, and translate efforts into real gains. Seeing these gains and experiencing this support demonstrates to the organization that there is real value in innovation at the tactical level. Innovation without consolidating gains does not lead to enduring change. Successful experiments and demonstrations, especially those with disruptive qualities, are celebrated amongst the small group driving the effort, but are not scaled appropriately or shared to create meaningful change unless leaders make specific and thoughtful efforts to consolidate gains and translate the disruption back into the system.

In Army doctrine, consolidating gains means transforming temporary success into enduring outcomes. Civilian industry recognizes the need for the same ability to move beyond short term wins in times of change, continue to overcome resistance, and produce change in interdependent systems. The requirements for consolidating gains of an unforeseen innovation are not predictable. Therefore, tactical innovation requires a leader with a blend of leadership and management skills; this is a person with the agility of mind to recognize innovation value despite uncertainty, understanding to manage innovation efforts without stomping them out, and the knowledge of the current system to understand how to institute change. The Army needs both skills, leadership and management, to translate successful innovation efforts into lasting change.

Leaders must look at supporting tactical innovation as part of their professional stewardship. Understanding the value of innovation and their role in stewarding these efforts is foundational to leader support. Without buy-in to the benefits of tactical innovation and an understanding of the long-term effects, there is no organizational incentive that will overcome the short-term focus. A logical connection of innovation study, education, principles, and history creates more probability for change than any short-term incentive. Leaders will need to guide, help, ask, resource, and encourage more than control, organize, direct, and standardize.

Leaders must look at supporting tactical innovation as part of their professional stewardship. Understanding the value of innovation and their role in stewarding these efforts is foundational to leader support. Without buy-in to the benefits of tactical innovation and an understanding of the long-term effects, there is no organizational incentive that will overcome the short-term focus. A logical connection of innovation study, education, principles, and history creates more probability for change than any short-term incentive. Leaders will need to guide, help, ask, resource, and encourage more than control, organize, direct, and standardize.

Without the balance between understanding of the current system and ability to manage the incubation and acceleration of new ideas, even successful experiments will not reach their potential. This requires more leaders to understand not only the current system, but also the conditions and characteristics for innovation with different problem-solving approaches. Not all leaders can take advantage of a civilian program like Stanford’s Ignite or Innovation Fellows, but organizations like NavalX and Joint Special Operations University offer opportunities for courses in design thinking and agile product development. The Army can encourage these by creating additional skill identifiers or adding knowledge and skills on the Assignment Interactive Module resume. Investing in the skills necessary for managing innovation and blending them with knowledge of the current system is imperative to realizing gains. Leaders with this ability have long term outlooks and reduce obstacles for soldier solutions.

Conclusion

The three suggested mechanisms for change offered in this article are logically linked from innovation characteristics to current Army culture with consideration of past and current Army efforts. These methods require the Army, through its leaders across the force, to decouple ideas from experience, connect ideas to mature the ecosystem, and be equipped to consolidate innovation gains with leadership and management. It is important to highlight that these methods offer examples, not standards. The most important facet of these suggestions is the culture they reflect.

This article does not suggest structural or policy changes. It does not advocate for a particular organization standard within every unit. To do so would merely reinforce efforts with temporary impact. No number of new organizations or policies will create the ability for the Army to recognize and take advantage of change without the foundational culture conducive to innovation. This article attempts to link the attributes and value of innovation to the Army’s cultural shortfalls and exploit areas of potential to suggest mechanisms for an innovative culture that are tailored to fill a specific innovation gap. With this gap filled, AFC can better focus on strategic level innovation while enabling tactical innovation for a more holistic approach.

If you enjoyed this post, check out:

The Convergence: The Future of Ground Warfare with COL Scott Shaw and associated podcast

The Convergence: Innovating Innovation with Molly Cain and associated podcast

Dense Urban Hackathon – Virtual Innovation

“Once More unto The Breach Dear Friends”: From English Longbows to Azerbaijani Drones, Army Modernization STILL Means More than Materiel and The Myth of Agincourt and Lessons on Army Modernization, by Mr. Ian Sullivan

Mission Engineering and Prototype Warfare: Operationalizing Technology Faster to Stay Ahead of the Threat by The Strategic Cohort at the U.S. Army Tank Automotive Research, Development, and Engineering Center (TARDEC).

Four Elements for Future Innovation by Dr. Richard Nabors

The Changing Dynamics of Innovation

Innovation Isn’t Enough: How Creativity Enables Disruptive Strategic Thinking, by Heather Venable

>> REMINDER: Our Mad Scientist Writing Contest on Competition, Crisis, Conflict, and Change ENDS TODAY!!!

… but you still have time to send in your submissions. We want to know your thoughts regarding:

How will our competitors deny the U.S. Joint Force’s tactical, operational, and strategic advantages to achieve their objectives (i.e., win without fighting) in the Competition and Crisis Phases?

How will our adversaries seek to overmatch or counter U.S. Joint Force strengths in future Large Scale Combat Operations?

Submission guidelines are addressed on our contest flyer — deadline for submission is COB today, 15 March 2021!!!

Jim Armstrong is an active-duty Army officer. He is currently a student at the Army War College. His service includes assignment as a concept lead for the Joint Staff Innovation Group from 2016 to 2018.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).