“President Xi Jinping and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) want to achieve ‘the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation’ by 2049. The PRC will seek to increase its power and influence to shape world events to create an environment favorable to PRC interests, obtain greater U.S. deference to China’s interests, and fend off challenges to its reputation, legitimacy, and capabilities at home and abroad…. The PRC will continue trying to press Taiwan on unification…” — Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community, Office of the Director of National Intelligence, March 2025

[Editor’s Note: Army Mad Scientist welcomes guest blogger SGT Michael A. Cappelli II with his insightful submission exploring how our pacing threat, China, could leverage a natural disaster and weaponize humanitarian assistance to achieve fait accompli the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) goal of reunifying Taiwan with the Chinese mainland. Learn how the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA’s) Non-War Military Operations (NWMO) provide an operational basis for achieving this below the threshold of conflict — i.e., “Winning without Fighting,” per Sun Tzu’s The Art of War — Read on!]

Summary

Taiwan’s location in the Western Pacific makes the island highly susceptible to large-scale natural disasters. A significant natural disaster could prove the perfect excuse for China to use humanitarian aid and disaster relief as cover for an invasion of Taiwan. Non-War Military Operations (NWMO) provides the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) with an operational basis for using actions below the threshold of conflict, such as humanitarian aid and disaster relief, to achieve China’s political and military goals.

Introduction

Given the high stakes over a conflict for control of Taiwan, it is important to consider the possibility of the PLA utilizing military operations other than war as a viable strategy for capturing Taiwan. Originating with the U.S. military, the PLA has a similar operational concept known as Non-War Military Operations (NWMO).1 Articulated in the PLA’s Science of Military Strategy, NWMO covers several national security concerns that fall into the nebulous realm of hybrid warfare or gray zone tactics. Along the conflict continuum, NWMO bridges the gap between competition and crisis, linking Chinese competition concepts such as the Three Warfares with large-scale military operations. It is possible, through practice and preparation, that the PLA may utilize an NWMO-based strategy to move on some or all of Taiwan’s territory before Taiwan and the international community could react. Specifically, NWMO offers China the possibility of maximizing its position on the conflict continuum by weaponizing humanitarian assistance and disaster relief as a fait accompli to gain territory in the Taiwan Strait after a natural disaster.

The Science of Military Strategy sets out a clear definition of what NWMO are, the basic features of NWMO, and strategic guidance for conducting NWMO. The text describes four key reasons NWMO is an important component of PLA strategy: 1) Maintaining National Stability, 2) Deterring War, 3) Enhancing International Security Cooperation, and 4) Enhancing the Ability to Win Wars.2 Additionally, NWMO addresses specific national security concerns such as anti-terrorism operations, stability operations, peacekeeping, border control, and humanitarian aid and disaster relief.3 Amongst NWMO’s basic features, the Science of Military Strategy lists several that stand out in a conflict over  Taiwan, such as the PLA’s need for flexibility, narrative and information control, the need for the PLA to be ready for sudden, unexpected events like natural disasters, and the normalization of NWMO through frequent use.4 Finally, strategic guidance for NWMO indicates NWMO is more complex than standard military operations, are most often in response to an emergency, and are both multidomain and require input from civil and paramilitary elements.5

Taiwan, such as the PLA’s need for flexibility, narrative and information control, the need for the PLA to be ready for sudden, unexpected events like natural disasters, and the normalization of NWMO through frequent use.4 Finally, strategic guidance for NWMO indicates NWMO is more complex than standard military operations, are most often in response to an emergency, and are both multidomain and require input from civil and paramilitary elements.5

Analyzing a conflict over Taiwan within the conflict continuum, NWMO provide structure and guidance for PLA actions between competition and conflict. On the competition end of the spectrum lies the Three Warfares: public opinion warfare, psychological warfare, and legal warfare.6 Three Warfares ranges from manipulating media coverage of events to bad-faith use of legal rhetoric to give validity to Chinese territorial claims. The Three Warfares also brings together the PLA with other elements of the CCP and the Chinese state to sow confusion and build uncertainty that can be taken advantage of within the context of Chinese grand strategy.7  On the conflict end of the spectrum lies the PLA’s joint operations, combat actions against an adversarial force or military.8 The PLA lists five joint operations, three which are aimed at Taiwan. Joint operations can occur individually or in tandem, and they can be conducted by one or all branches of the PLA.9 In the middle of the conflict continuum lies crisis. NWMO fit this area well, providing a structured and deliberate military concept that easily swings from competition to conflict while building towards an ultimate military and political goal potentially short of conflict. The Science of Military strategy repeatedly points out that NWMO is meant for dealing with a crisis, an increasing reality within the Taiwan Strait. NWMO also fit with a PLA strategy of taking and holding territory from internal and external resistance as an ultimate military and political goal. Lastly, NWMO’s repeated emphasis on humanitarian aid and disaster relief foreshadows a possible PLA use of force against Taiwan at a time when Taiwan is least prepared for a military excursion.

On the conflict end of the spectrum lies the PLA’s joint operations, combat actions against an adversarial force or military.8 The PLA lists five joint operations, three which are aimed at Taiwan. Joint operations can occur individually or in tandem, and they can be conducted by one or all branches of the PLA.9 In the middle of the conflict continuum lies crisis. NWMO fit this area well, providing a structured and deliberate military concept that easily swings from competition to conflict while building towards an ultimate military and political goal potentially short of conflict. The Science of Military strategy repeatedly points out that NWMO is meant for dealing with a crisis, an increasing reality within the Taiwan Strait. NWMO also fit with a PLA strategy of taking and holding territory from internal and external resistance as an ultimate military and political goal. Lastly, NWMO’s repeated emphasis on humanitarian aid and disaster relief foreshadows a possible PLA use of force against Taiwan at a time when Taiwan is least prepared for a military excursion.

Taiwan’s Natural Disaster Potential

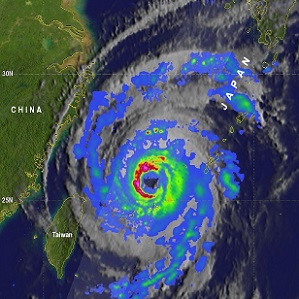

Taiwan’s location in the western Pacific makes it a disaster-prone area. Typhoons, earthquakes, and tsunamis are of particular concern, with local sources indicating Taiwan ranks first in the world in natural disaster risk.10 The island lays atop an area of active seismic activity, averaging 25 earthquakes a year.11 Taiwan’s strongest earthquake occurred in 1999 and measured a magnitude 7.7. While the epicenter was located in central Taiwan, the earthquake was felt nationwide and resulted in 2,400 deaths, thousands of collapsed houses, and more than 100,000 people homeless.12 While the spring 2024 earthquakes in Hualien did not result in the same widespread damage and destruction seen in 1999, the Hualien earthquakes indicate that strong, damaging earthquakes are not a thing of the past.13

Typhoons are also of particular concern for Taiwan. Approximately 80 storms have struck Taiwan since the 1970s and their intensity has increased as a result of climate change.14 Typhoons and their aftereffects can be incredibly damaging and debilitating to Taiwan. A 2009 typhoon damaged the Southern Cross-Island Highway so severely, it took 13 years to reopen the highway in its entirety.15 The Science of Military Strategy’s continued emphasis on humanitarian aid and disaster relief as NWMO take on another dimension given the disaster-prone nature of Taiwan. Climate change is expected to contribute to more extreme weather events in the region, and Taiwan’s geographic proximity to China makes a humanitarian response an excellent guise for PLA action against Taiwanese-controlled territory, especially since one of the main agencies for administering Chinese disaster aid is the PLA.16

Typhoons are also of particular concern for Taiwan. Approximately 80 storms have struck Taiwan since the 1970s and their intensity has increased as a result of climate change.14 Typhoons and their aftereffects can be incredibly damaging and debilitating to Taiwan. A 2009 typhoon damaged the Southern Cross-Island Highway so severely, it took 13 years to reopen the highway in its entirety.15 The Science of Military Strategy’s continued emphasis on humanitarian aid and disaster relief as NWMO take on another dimension given the disaster-prone nature of Taiwan. Climate change is expected to contribute to more extreme weather events in the region, and Taiwan’s geographic proximity to China makes a humanitarian response an excellent guise for PLA action against Taiwanese-controlled territory, especially since one of the main agencies for administering Chinese disaster aid is the PLA.16

Weaponizing Disaster Relief

A Chinese fait accompli disguised as humanitarian aid and disaster relief will likely take on a multidomain approach, with the PLA working to take territory and disrupt an already overburdened Taiwanese government and society. Natural disasters usually result in damage to infrastructure, civilians relocating to evacuation shelters, and portions of the armed forces preparing and assisting with disaster relief and assistance. Under these circumstances, cyber, information, and electronic warfare against Taiwan could have devastating effects that China could easily exploit. China has a well-established history of targeting Taiwan with disinformation attacks and has the ability to disrupt Taiwanese physical and digital infrastructure.17 It is not hard to imagine the advantage China would gain from cyber, intelligence and electronic warfare attacks on a stressed civilian population while simultaneously targeting the very tools civilian and military disaster relief personnel need to improve safety and security. Add to that mix AI-generated media showing what appears to be Taiwanese leaders requesting China’s assistance, and the potential impact of NWMO only grows as confusion and disinformation spread. China debuted its first AI news anchor in 2018 to help spread pro-Chinese influence online, and AI technology has developed significantly in that time.18 It is not a stretch to imagine these tactics being used to exploit a confused populace, incite civilian anger against the Taiwanese government, or disrupt troop and first responder movements.

Within more traditional domains, PLA activities will likely resemble a mix of Taiwan-focused joint operations as part of a humanitarian aid and disaster relief NWMO. China’s continued military activities within Taiwan’s ADIZ and territorial waters show the PLA can launch air and naval units around Taiwan quickly, with the goal of taking Taiwan and keeping outside military intervention at bay.19 Depending on how the operation unfolds, the PLA’s growing rocket force, paramilitary forces, and drone capabilities are likely to play a significant role.

While the PLA has limited air assault, airborne, and amphibious capabilities, concentrating those capabilities in a few, strategic locations could be enough to establish viable beachheads or completely capture some of Taiwan’s outlying territories. The PLA has put significant effort over the past decade into increasing its air assault capabilities with an emphasis on supporting ground forces.20 The PLA’s airborne corps and air force also continue to improve training, preparation, and airlift capability.21 Most importantly, the PLA continues to improve training, capabilities, and joint support for amphibious operations in preparation for a conflict over Taiwan.22 In addition to traditional amphibious assault capabilities, the PLA utilizes roll-on/roll-off (RO-RO) vessels, essentially civilian vehicle ferries, in Chinese amphibious exercises.23 Dual-use RO/ROs present a difficult challenge for countering a Chinese NWMO against Taiwan. RO-ROs are vessels normally found in the waters off China, and militarized variants could make it extremely close to Taiwanese-held territory before being detected. Even more troubling, they could help boost the localized effectiveness of China’s amphibious capabilities against Taiwan’s outlying islands during NWMO.

While the PLA has limited air assault, airborne, and amphibious capabilities, concentrating those capabilities in a few, strategic locations could be enough to establish viable beachheads or completely capture some of Taiwan’s outlying territories. The PLA has put significant effort over the past decade into increasing its air assault capabilities with an emphasis on supporting ground forces.20 The PLA’s airborne corps and air force also continue to improve training, preparation, and airlift capability.21 Most importantly, the PLA continues to improve training, capabilities, and joint support for amphibious operations in preparation for a conflict over Taiwan.22 In addition to traditional amphibious assault capabilities, the PLA utilizes roll-on/roll-off (RO-RO) vessels, essentially civilian vehicle ferries, in Chinese amphibious exercises.23 Dual-use RO/ROs present a difficult challenge for countering a Chinese NWMO against Taiwan. RO-ROs are vessels normally found in the waters off China, and militarized variants could make it extremely close to Taiwanese-held territory before being detected. Even more troubling, they could help boost the localized effectiveness of China’s amphibious capabilities against Taiwan’s outlying islands during NWMO.

Vulnerabilities and Counter Measures

Taiwan’s outlying territories are likely the most vulnerable to a Chinese NWMO disguised as humanitarian aid and disaster relief. The islands of Kinmen and Matsu are mere miles off the Chinese coast and would be extremely difficult to reinforce.24 Damage to undersea communications cables off Matsu Island in the spring of 2023 indicates that China is practicing ways to disrupt communication between Taiwan and its outlying areas.25 This low-tech action against such a vital piece of infrastructure could easily be replicated during an actual PLA operation against Taiwanese territory. The PLA’s Joint-Sword 2024A military exercise included activity around all of Taiwan’s outlying islands for the first time since these exercises began in 2022.26

The capture of Taiwan’s outlying islands would provide strategic and symbolic gains for the PLA. Taiwan’s outlying islands easily fall within range of Chinese missile systems, and the PLA’s amphibious and air assault capabilities.27 Starting in the spring of 2024, the Chinese Coast Guard now makes regular incursions into Kinmen’s maritime boundaries, pushing the limits of acceptable behavior in the region.28 The Penghu islands, located 30 miles southwest of Taiwan, would not necessarily be safer in a NWMO disguised as humanitarian aid and disaster relief. The capture of Penghu would be especially beneficial to the PLA, giving Chinese forces territory to help secure supply lines, stage troops and weapons platforms, and extend anti-access, area denial (A2/AD) capabilities for a future invasion of Taiwan.29 A Chinese capture of Taiwan’s outlying territories would also present a good test of international reaction to Chinese military action against Taiwan.

To prepare for a possible Chinese fait accompli disguised as humanitarian aid and disaster relief, Taiwan will need to ensure it has resilient critical infrastructure. Taiwan’s ability to recover quickly from a natural disaster would lessen Chinese justification for NWMOs and reduce the PLA’s window of opportunity to conduct NWMOs. While relatively close in magnitude, the 2024 Hualien earthquakes were significantly less destructive than the widespread 1999 earthquake. While better building codes played a significant part in reducing deaths and property damage, coordination amongst first responders, the central government, and Taiwanese armed forces showed a high level of disaster resiliency in Taiwan.30 However, a focus on critical infrastructure in outlying territories is not without risk, since such efforts could result in wasted resources, equipment, and specially trained personnel in difficult to defend areas. In contrast, resiliency in Taiwan’s outlying islands may prove a deterrent to Chinese military action by creating a level of uncertainty in Chinese mission success. Even if China is not deterred, the PLA could miscalculate the forces needed to take Taiwan’s outlying islands.31 Such a miscalculation could result in a military setback and force the PLA to over commit units to taking these outlying territories instead of Taiwan itself. This could provide Taiwan the opportunity to push back China, possibly with international support.

Another option for Taiwan to hold off a possible Chinese fait accompli disguised as humanitarian aid and disaster relief would be to improve civilian preparedness and disaster recovery. Traditionally, the Taiwanese military is the primary first responder to natural disasters.32 Opportunity does exist to transition disaster response away from military units, especially with Taiwan working to boost civil defense preparedness amongst the general population in case of a war with China.33 Private, civil defense preparation programs for civilians, that emphasize disaster relief, are also increasing in popularity in Taiwan.34 While these private organizations range in size from local groups to large-scale entities, they all find their origin in a desire to help Taiwan escape the tragic political fate of Hong Kong and the war-torn reality of Ukraine.35 There is risk involved with this strategy. Taiwan’s armed forces are in need of reforms and focusing on noncombat operations is likely not the best place to start.36 Shifting natural disaster response away from the Taiwanese military may also reduce disaster response efficiency. This may also prolong a natural disaster’s impact, increasing the very justification China would need to conduct a humanitarian aid and disaster relief-based fait accompli.

Another option for Taiwan to hold off a possible Chinese fait accompli disguised as humanitarian aid and disaster relief would be to improve civilian preparedness and disaster recovery. Traditionally, the Taiwanese military is the primary first responder to natural disasters.32 Opportunity does exist to transition disaster response away from military units, especially with Taiwan working to boost civil defense preparedness amongst the general population in case of a war with China.33 Private, civil defense preparation programs for civilians, that emphasize disaster relief, are also increasing in popularity in Taiwan.34 While these private organizations range in size from local groups to large-scale entities, they all find their origin in a desire to help Taiwan escape the tragic political fate of Hong Kong and the war-torn reality of Ukraine.35 There is risk involved with this strategy. Taiwan’s armed forces are in need of reforms and focusing on noncombat operations is likely not the best place to start.36 Shifting natural disaster response away from the Taiwanese military may also reduce disaster response efficiency. This may also prolong a natural disaster’s impact, increasing the very justification China would need to conduct a humanitarian aid and disaster relief-based fait accompli.

The Taiwanese government and people have not remained complacent to the threat of Chinese military action. During Taiwan’s 2023 Han Kuang military exercise, Taiwan’s armed forces conducted their first military exercise to defend the country’s main airport in addition to regular air-raid and amphibious assault preparations.37 Public polling in Taiwan indicates an increased interest in defending the island, especially after the Russian invasion of Ukraine.38 Even though Taiwan does have potential military disadvantages compared to China, the quality and strength of Taiwan’s political leadership and the island’s high degree of social cohesion may prove to be decisive factors in the island’s defense.39 Stay-behind forces may also play an important role in complicating a Chinese fait accompli disguised as humanitarian aid and disaster relief. Stay-behind forces are military units, resistance networks, and associated personnel that can undertake supporting activities behind enemy lines from reconnaissance, to sabotage, to more traditional special forces activities.40 Taiwan’s complex terrain provides an excellent environment for employing irregular forces in captured areas. Even on Taiwan’s outlying islands, stay-behind forces conducting non-military actions can still prove valuable to disrupting PLA supply and staging areas and sea lines of communication. Preparation however may not stop China if it feels conditions are in its favor to take Taiwan.

Conclusion

While a natural disaster is hard to predict, it could provide excellent cover for a Chinese fait accompli against Taiwan. If an NWMO disguised as humanitarian aid and disaster relief is fast, targeted, and decisive, the PLA might be able to take some or all of Taiwan’s territory while dissuading the US and other regional partners from taking action. On an almost daily basis, the PLA is normalizing provocative military actions, pushing the boundaries of China’s geostrategic space, and refining increasingly complex, joint-services operations. All of these indicate a PLA strategy centered on swift, decisive action against Taiwan before a strong international response can be mounted. A successful Chinese fait accompli would be devastating for Taiwan and allow the PLA to quickly shift from occupation to culminating military operations against what is left of Taiwan’s armed forces and leadership. An outright war for Taiwan would be a costly endeavor in personnel and materiel, and have negative implications for international stability and economic prosperity. To avoid these pitfalls, NWMO present China a viable alternative to outright war. Within the conflict continuum, the PLA is already implementing a number of Crisis tactics in the region that both align with NMWO and show the PLA’s growing military capabilities. Given these realities, an examination of PLA activity towards Taiwan indicates a strong likelihood that NWMO are ongoing in expectation of an exploitable opportunity such as a natural disaster.

If you enjoyed this post, review the TRADOC Pamphlet 525-92, The Operational Environment 2024-2034: Large-Scale Combat Operations

Explore the TRADOC G-2‘s Operational Environment Enterprise web page, brimming with authoritative information on the Operational Environment and how our adversaries fight, including:

Our China Landing Zone, full of information regarding our pacing challenge, including ATP 7-100.3, Chinese Tactics, BiteSize China weekly topics, People’s Liberation Army Ground Forces Quick Reference Guide, and our thirty-plus snapshots captured to date addressing what China is learning about the Operational Environment from Russia’s war against Ukraine (note that a DoD Common Access Card [CAC] is required to access this last link).

Our Russia Landing Zone, including the BiteSize Russia weekly topics. If you have a CAC, you’ll be especially interested in reviewing our weekly RUS-UKR Conflict Running Estimates and associated Narratives, capturing what we learned about the contemporary Russian way of war in Ukraine over the past two years and the ramifications for U.S. Army modernization across DOTMLPF-P.

Our Iran Landing Zone, including the Iran Quick Reference Guide and the Iran Passive Defense Manual (both require a CAC to access).

Our Running Estimates SharePoint site (also requires a CAC to access) — documenting what we’re learning about the evolving OE. Contains our monthly OE Running Estimates, associated Narratives, and the 2QFY24, 3QFY24, 4QFY24, and 1QFY25 OE Assessment TRADOC Intelligence Posts (TIPs).

Then review the following related Mad Scientist Laboratory content addressing China, our pacing threat, and relevant aspects of the Operational Environment:

Operation Northeast Monsoon: The Reunification of Taiwan, by Sherman Barto

“No Option is Excluded” — Using Wargaming to Envision a Chinese Assault on Taiwan, Three Dates, Three Windows, and All of DOTMLPF-P, China and Russia: Achieving Decision Dominance and Information Advantage, and Seven Reflections of a “Red Commander” — Lessons Learned Playing the Adversary in DoD Wargames, by Ian Sullivan

The Most Consequential Adversaries and associated podcast, with GEN Charles A. Flynn (USA-Ret.)

Volatility in the Pacific: China, Resilience, and the Human Dimension and associated podcast, with General Robert Brown (USA-Ret.)

How China Fights and associated podcast

Flash-Mob Warfare: Whispers in the Digital Sandstorm (Parts 1 and 2), by Dr. Robert E. Smith

China’s PLA Modernization through the DOTMLPF-P Lens, by Dr. Jacob Barton

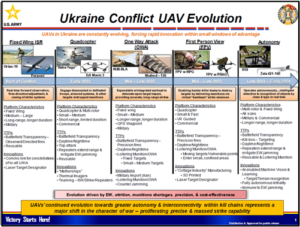

The PLA and UAVs – Automating the Battlefield and Enhancing Training

A Chinese Perspective on Future Urban Unmanned Operations

China: “New Concepts” in Unmanned Combat and Cyber and Electronic Warfare

The PLA: Close Combat in the Information Age and the “Blade of Victory”

China: Building Regional Hegemony

Intelligentization and the PLA’s Strategic Support Force, by Col (s) Dorian Hatcher

“Intelligentization” and a Chinese Vision of Future War

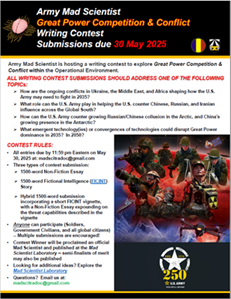

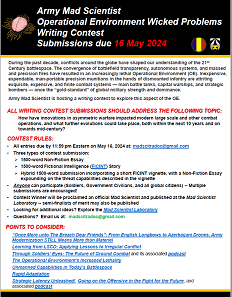

>>>>Reminder: Army Mad Scientist wants to crowdsource your thoughts on Great Power Competition & Conflict — check out the flyer describing our latest writing contest.

>>>>Reminder: Army Mad Scientist wants to crowdsource your thoughts on Great Power Competition & Conflict — check out the flyer describing our latest writing contest.

All entries must address one of the following writing prompts:

How are the ongoing conflicts in Ukraine, the Middle East, and Africa shaping how the U.S. Army may need to fight in 2035?

What role can the U.S. Army play in helping the U.S. counter Chinese, Russian, and Iranian influence across the Global South?

How can the U.S. Army counter growing Russian/Chinese collusion in the Arctic, and China’s growing presence in the Antarctic?

What emergent technology(ies) or convergences of technologies could disrupt Great Power dominance in 2035? In 2050?

We are accepting three types of submissions:

-

-

- 1500-word Non-Fiction Essay

-

-

-

- 1500-word Fictional Intelligence (FICINT) Story

-

-

-

- Hybrid 1500-word submission incorporating a short FICINT vignette, with a Non-Fiction Essay expounding on the threat capabilities described in the vignette

-

Anyone can participate (Soldiers, Government Civilians, and all global citizens) — Multiple submissions are encouraged!

All entries are due NLT 11:59 pm Eastern on May 30, 2025 at: madscitradoc@gmail.com

Click here for additional information on this contest — we look forward to your participation!

About the Author: SGT Michael A. Cappelli II is a U.S. Army All Source Intelligence Analyst with the 25ID G2. He holds a B.A. in Asian Studies and Political Science from Rice University. SGT Cappelli learned about Cross Strait issues from the perspectives of all parties involved through his studies in both mainland China and Taiwan, attendance of GIS Taiwan, and internship at the Baker Institute for Public Policy.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

1 Bilms, Kevin. “Beyond War and Peace: The PLA’s “Non-War Military Activities” Concept.” Modern Warfare Institute, United States Military Academy. Last Modified January 26, 2022. https://mwi.usma.edu/beyond-war-and-peace-the-plas-non-war-military-activities-concept/.

2 Xiao, Tianliang, ed. The Science of Military Strategy 2020. Translated by China Aerospace Studies Institute. Beijing: National Defense University Press, 2020. Last Modified January 26, 2022.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Mattis, Peter. “China’s ‘Three Warfares’ in Perspective.” War on the Rocks. Last Modified January 30, 2018. https://warontherocks.com/2018/01/chinas-three-warfares-perspective/.

7 Zhao, Peter. “Chinese Political Warfare: A Strategic Tautology? The Three Warfares and the Centrality of Political Warfare within Chinese Strategy.” The Strategy Bridge. Last Modified August 28, 2023. https://thestrategybridge-org.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2023/8/28/chinese-political-warfare-a-strategic-tautology?format=amp.

8 Wuthnow, Joel, Derek Grossman, Philip C. Saunders, Andrew Scobell, and Andrew N.D. Yang, eds. Crossing The Strait: China’s Military Preparation for War with Taiwan. Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press, 2022.

9 Easton, Ian. “China’s Top Five War Plans.” Project 2049. Last Modified January 06, 2019. https://project2049.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Chinas-Top-Five-War-Plans_Ian_Easton_Project2049.pdf.

10 Taoyuan Disaster Education Center. “Natural Hazards”. Taoyuan Disaster Education Center. Last Modified September 08, 2023. https://tydec.tyfd.gov.tw/EN/About/Area/Area_A.

11 Shan, Shelly. “Taiwan’s seismic activity has risen this year: CWB”. Taipei Times. Last Modified October, 12 2022. https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2022/10/12/2003786869.

12 Encyclopedia Britannica. “Taiwan earthquake of 1999.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Last Modified May 02, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/event/Taiwan-earthquake-of-1999.

13 Lee, Yimou, and Fabian Hamacher. “Taiwan’s strongest earthquake in 25 years kills 9 people, 50 missing.” Reuters. Last Modified April 03. 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/strong-72-magnitude-earthquake-hits-taipei-2024-04-03/.

14 Pandey, Ravi S. and Yuel-an Liou. “Typhoon strength rising in the past four decades.” Weather and Climate Extremes, v. 36, June (2022). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212094722000329.

15 Chang, Wayne. “One of Taiwan’s most beautiful roads has reopened.” CNN. Last Modified May 06, 2022. https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/taiwan-southern-cross-island-highway-reopens-intl-hnk/index.html.

16 Kuo, Naiyu, Rosie Levine, and Andrew Scobell, Ph.D. “Stress Test: the April Earthquake and Taiwan’s Resilience.” United States Institute of Peace. Last Modified May 22, 2024. https://www.usip.org/publications/2024/05/stress-test-april-earthquake-and-taiwans-resilience.

17 Framer, Brit M. “China’s cyber assault on Taiwan.” CBS News. Last Modified June 18, 2023. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/china-cyber-assault-taiwan-60-minutes-2023-06-18/.

18 RFA Staff. “China’s deepfake anchors spread disinformation on social media, Graphika says.” Radio Free Asia. Last Modified February 08, 2023. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/china-deepfake-02082023032941.html.

19 Blanchard, B. and Lee, Y. “China ends Taiwan drills after practicing blockades, precision strikes.” Reuters. Last Modified April 10, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/japan-following-chinas-taiwan-drills-with-great-interest-2023-04-10/.

20 McCauley, Kevin. “The People’s Liberation Army’s Evolving Close Air Support Capability.” Foreign Military Studies Office, Foreign Perspective Brief. January (2024). https://fmso.tradoc.army.mil/2023/the-peoples-liberation-armys-evolving-close-air-support-capability-kevin-mccauley/.

21 Fu, Daniel. “PLA Airborne Capabilities and Paratrooper Doctrine for Taiwan.” China Brief, V. 23, 11 (2023). https://jamestown.org/program/pla-airborne-capabilities-and-paratrooper-doctrine-for-taiwan/.

22 Blasko, Dennis J. “China Maritime Report No. 20: The PLA Army Amphibious Force.” China Maritime Studies Institute China Maritime Report No. 20, v. 4 (2022). https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1019&context=cmsi-maritime-reports.

23 Funaiole, Matthew P., Brian Hart, Jaehyun Han, and Jenifer Jun. “China Accelerates Construction of ‘Ro-Ro’ Vessels, with Potential Military Implications.” China Power CSIS. Last Modified October 11, 2023. https://chinapower.csis.org/analysis/china-construct-ro-ro-vessels-military-implications/.

24 Chubb, Andrew. “Taiwan Strait Crises: Island Seizure Contingencies.” Asia Society. Last Modified February, 22 2023. https://asiasociety.org/policy-institute/taiwan-strait-crises-island-seizure-contingencies-0.

25 Hsu, Jason. and Charles Mok. “Taiwan’s island internet cutoff highlights infrastructure risks.” Nikkei Asia. Last Modified May 31, 2023. https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Taiwan-s-island-internet-cutoff-highlights-infrastructure-risks.

26 Lin, Bonny and Brian Hart. “How Is China Responding to the Inauguration of Taiwan’s President William Lai?” China Power CSIS. Last Modified May 23, 2024. https://chinapower.csis.org/china-respond-inauguration-taiwan-william-lai-joint-sword-2024a-military-exercise/.

27 U.S. Department of Defense. Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China. 2023. https://media.defense.gov/2023/Oct/19/2003323409/-1/-1/1/2023-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF.

28 Hioe, Brian. “China Seeks to Influence Taiwan Through Outlying Islands.” New Bloom Magazine. Last Modified May 10, 2024. https://newbloommag.net/2024/05/10/tw-china-outlying-islands/.

29 Chang, Sean and Rebecca Bailey. “Control Without Invasion: Other Actions China Could Take Against Taiwan.” Barron’s. Last Modified June 16, 2022. https://www.barrons.com/news/control-without-invasion-other-actions-china-could-take-against-taiwan-01655438409.

30 Kuo, Naiyu, Rosie Levine, and Andrew Scobell, Ph.D. “Stress Test: the April Earthquake and Taiwan’s Resilience.” United States Institute of Peace. Last Modified May 22, 2024. https://www.usip.org/publications/2024/05/stress-test-april-earthquake-and-taiwans-resilience.

31 Brimelow, Benjamin. “Taiwan’s remote islands are on the frontline with China – sometimes only a few hundred yards from Chinese troops.” Business Insider. Last Modified December 28, 2022. https://www.businessinsider.com/taiwans-outlying-islands-are-on-the-frontline-with-china-2022-12.

32 Chiang, Ariel P.H. “Taiwan’s Natural Disaster Response and Military – Civilian Partnerships.” Global Taiwan Brief, v. 3, 10 (2018). https://globaltaiwan.org/2018/05/taiwans-natural-disaster-response-and-military-civilian-partnerships/.

33 Yeh, J. “Military releases new civil defense handbook amid backlash.” Central News Agency. Last Modified June 13, 2023. https://focustaiwan.tw/politics/202306130007.

34 Hsiao, Russell. “ Taiwan’s Bottom-Up Approach to Civil Defense Preparedness.” Global Taiwan Brief, v. 7, 10 (2022). https://globaltaiwan.org/2022/09/taiwans-bottom-up-approach-to-civil-defense-preparedness/.

35 Kelter, Frederik. “Fearing war with China, civilians in Taiwan prepare for disaster.” Al Jazeera. Last Modified May 25, 2024. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/longform/2024/5/25/fearing-war-with-china-civilians-in-taiwan-prepare-for-disaster.

36 Oswald, Rachel. “Taiwan’s military needs overhaul amid China threat, critics say.” Roll Call. Last Modified September 28, 2022. https://rollcall.com/2022/09/28/taiwans-military-needs-overhaul-amid-china-threat-critics-say/.

37 Staff Writer with CNA. “Military Conducts first anti-takeover drills at Taoyuan.” Taipei Times. Last Modified July 27, 2023. https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/front/archives/2023/07/27/2003803809.

38 Wu, Charles K.S., Yao-Yuan Yeh, Fang-Yu Chen, and Austing Horng-En Wang. “Why NGOs Are Boosting Support for the Self-Defense in Taiwan.” The National Review. Last Modified February 22, 2023. https://nationalinterest.org/feature/why-ngos-are-boosting-support-self-defense-taiwan-206240.

39 Heath, Timothy R. “Taiwan’s Will to Fight May Be Stronger Than You Think.” RAND. Last Modified June 27, 2023. https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2023/06/taiwans-will-to-fight-may-be-stronger-than-you-think.html.

40 Petit, Brian. “Should I Stay or Should I Go? Stay-Behind Force Decision-Making.” War on the Rocks. Last Modified November 08, 2023. https://warontherocks.com/2023/11/should-i-stay-or-should-i-go-stay-behind-force-decision-making/.

Brian Train

Brian Train LTC Matt Rasmussen‘s

LTC Matt Rasmussen‘s  In an era of digital warfare and rapid technological advancements shaping the battlefield, the military stands at a pivotal crossroads. Embracing artificial intelligence (AI) isn’t merely a strategic choice but a necessity, as recent research highlights (Chen et al., 2020; Daniels & Chang, 2021; Ryseff et al., 2022). The transformation of the digital landscape necessitates a reevaluation of training paradigms to maintain operational effectiveness and a technological edge. Clinging to outdated training methods exposes Soldiers to vulnerabilities and hinders their competitiveness in an increasingly complex digital environment (Bagchi et al., 2020). The

In an era of digital warfare and rapid technological advancements shaping the battlefield, the military stands at a pivotal crossroads. Embracing artificial intelligence (AI) isn’t merely a strategic choice but a necessity, as recent research highlights (Chen et al., 2020; Daniels & Chang, 2021; Ryseff et al., 2022). The transformation of the digital landscape necessitates a reevaluation of training paradigms to maintain operational effectiveness and a technological edge. Clinging to outdated training methods exposes Soldiers to vulnerabilities and hinders their competitiveness in an increasingly complex digital environment (Bagchi et al., 2020). The  specialty (MOS) training and the professional military education (PME) system: personalized and tailored training (Chen et al., 2020), enhanced training effectiveness, and improved efficiency and cost-effectiveness. By integrating AI into its training systems, the Army can ensure Soldiers receive the precise knowledge and skills they need when they need it, maximizing resource utilization and cost savings.

specialty (MOS) training and the professional military education (PME) system: personalized and tailored training (Chen et al., 2020), enhanced training effectiveness, and improved efficiency and cost-effectiveness. By integrating AI into its training systems, the Army can ensure Soldiers receive the precise knowledge and skills they need when they need it, maximizing resource utilization and cost savings. Imagine a Soldier struggling with land navigation receiving immersive virtual reality simulations focused on land navigation fundamentals while another adept in small team tactics hones skills through engaging augmented reality scenarios. In PME, AI can curate courses for Soldiers preparing for specific deployments, simulating realistic battlefield situations and leadership challenges tailored to their assigned environments (Dasgupta & Wendler, 2019). This personalized approach fosters more profound understanding, faster skill acquisition, and a more adaptable and ready force. Training effectiveness could increase exponentially through an extensive and immersive training environment controlled by AI and personalized to an individual’s needs.

Imagine a Soldier struggling with land navigation receiving immersive virtual reality simulations focused on land navigation fundamentals while another adept in small team tactics hones skills through engaging augmented reality scenarios. In PME, AI can curate courses for Soldiers preparing for specific deployments, simulating realistic battlefield situations and leadership challenges tailored to their assigned environments (Dasgupta & Wendler, 2019). This personalized approach fosters more profound understanding, faster skill acquisition, and a more adaptable and ready force. Training effectiveness could increase exponentially through an extensive and immersive training environment controlled by AI and personalized to an individual’s needs. Noncommissioned Officer struggling with leadership decision-making or concepts; AI can identify this weakness and adapt PME coursework with more complex practical coursework and data-driven analysis exercises, fostering deeper learning and preparing Soldiers for real-world challenges with greater confidence (Goldberg et al., 2017). By tailoring coursework to the individual as needed, AI would improve human instructors’ ability to prioritize their own time with trainees and increase the overall cost-effectiveness of training for the Army.

Noncommissioned Officer struggling with leadership decision-making or concepts; AI can identify this weakness and adapt PME coursework with more complex practical coursework and data-driven analysis exercises, fostering deeper learning and preparing Soldiers for real-world challenges with greater confidence (Goldberg et al., 2017). By tailoring coursework to the individual as needed, AI would improve human instructors’ ability to prioritize their own time with trainees and increase the overall cost-effectiveness of training for the Army. training, instructors can focus on personalized feedback and mentorship. This saves time and money and empowers instructors to provide more high-value support to individual Soldiers (Bagchi et al., 2020). By embracing AI’s efficiency and cost-saving potential, the Army can demonstrate its commitment to operational excellence and responsible stewardship of resources. Despite increased efficiency and cost-effectiveness benefits, a more profound concern looms over the outdated nature of the Army’s training.

training, instructors can focus on personalized feedback and mentorship. This saves time and money and empowers instructors to provide more high-value support to individual Soldiers (Bagchi et al., 2020). By embracing AI’s efficiency and cost-saving potential, the Army can demonstrate its commitment to operational excellence and responsible stewardship of resources. Despite increased efficiency and cost-effectiveness benefits, a more profound concern looms over the outdated nature of the Army’s training. a transformative shift in its training paradigm to maintain its competitive edge. The current methods, rooted in traditional approaches, must improve the development of the agile, adaptable, and effective force needed for future conflicts. Addressing these shortcomings necessitates a bold step: leveraging AI’s power to revolutionize how Soldiers train.

a transformative shift in its training paradigm to maintain its competitive edge. The current methods, rooted in traditional approaches, must improve the development of the agile, adaptable, and effective force needed for future conflicts. Addressing these shortcomings necessitates a bold step: leveraging AI’s power to revolutionize how Soldiers train. The Army has progressed across many facets of caring for Soldiers and supporting them through life’s changes. How the Army trains its Soldiers has remained unchanged over the past several decades. One glaringly obvious issue with these antiquated training strategies is the cookie-cutter approach that fails to meet individual Soldiers’ needs.

The Army has progressed across many facets of caring for Soldiers and supporting them through life’s changes. How the Army trains its Soldiers has remained unchanged over the past several decades. One glaringly obvious issue with these antiquated training strategies is the cookie-cutter approach that fails to meet individual Soldiers’ needs. example is a Soldier being trained as a cyber specialist. Suppose that a Soldier struggles to meet specific educational gates because of the cookie-cutter training being provided and eventually fails the course. In that case, the Army has lost a potential asset and wasted training time and dollars on that individual. By analyzing individual data and learning styles, AI can craft dynamic training paths that cater to each Soldier’s unique needs, maximizing their potential and ensuring efficient skill acquisition (Chen et al., 2020). By assisting Soldiers in learning how they best receive information, the Army would increase base knowledge levels and pass ratings for critical career fields in this digital era. With current training methodologies, providing personalized and adaptable training is too costly for the Army to consider.

example is a Soldier being trained as a cyber specialist. Suppose that a Soldier struggles to meet specific educational gates because of the cookie-cutter training being provided and eventually fails the course. In that case, the Army has lost a potential asset and wasted training time and dollars on that individual. By analyzing individual data and learning styles, AI can craft dynamic training paths that cater to each Soldier’s unique needs, maximizing their potential and ensuring efficient skill acquisition (Chen et al., 2020). By assisting Soldiers in learning how they best receive information, the Army would increase base knowledge levels and pass ratings for critical career fields in this digital era. With current training methodologies, providing personalized and adaptable training is too costly for the Army to consider. requirements. This inefficiency burdens human resources and hinders the Army’s ability to keep pace with the rapid advancements in technology and tactics. By automating administrative tasks, optimizing resource allocation, and dynamically generating and adapting training materials, AI can drastically improve the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the training development process (Bagchi et al., 2020). As the pace and characteristics of war continue to change with the increase of technology worldwide, the Army will need to add new MOS’s and adapt existing ones to meet commanders’ needs on the battlefield. AI provides the opportunity to streamline the updating of existing MOS training and create entirely new training paths for career fields the Army doesn’t even know it needs. In those instances, having the capacity to publish new training material nearly instantly would significantly increase the Army’s ability to adapt to changing threats.

requirements. This inefficiency burdens human resources and hinders the Army’s ability to keep pace with the rapid advancements in technology and tactics. By automating administrative tasks, optimizing resource allocation, and dynamically generating and adapting training materials, AI can drastically improve the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the training development process (Bagchi et al., 2020). As the pace and characteristics of war continue to change with the increase of technology worldwide, the Army will need to add new MOS’s and adapt existing ones to meet commanders’ needs on the battlefield. AI provides the opportunity to streamline the updating of existing MOS training and create entirely new training paths for career fields the Army doesn’t even know it needs. In those instances, having the capacity to publish new training material nearly instantly would significantly increase the Army’s ability to adapt to changing threats. integration isn’t just about efficiency; it’s about ensuring the Army’s ability to protect national interests and maintain its competitive edge in an increasingly complex and technology-driven world.

integration isn’t just about efficiency; it’s about ensuring the Army’s ability to protect national interests and maintain its competitive edge in an increasingly complex and technology-driven world. classroom lectures encountering a complex battlefield scenario requiring quick decision-making and adaptability. With AI’s immersive training experiences, such Soldiers can avoid being unprepared and vulnerable in real-world operations (Chen et al., 2020). Mastering an Army specialty demands routine memorization of procedures, a deep understanding of underlying principles, and the ability to apply them creatively in diverse situations. The current training approach falls short of providing the breadth and depth of knowledge needed to equip Soldiers for true mastery. This reduction in individual and collective readiness jeopardizes mission success and puts Soldier’s lives at unnecessary risk. Compounding the concerns about Soldier preparedness is the stark reality of wasted resources. The inefficiencies in the current training system drive costs without delivering the desired outcomes.

classroom lectures encountering a complex battlefield scenario requiring quick decision-making and adaptability. With AI’s immersive training experiences, such Soldiers can avoid being unprepared and vulnerable in real-world operations (Chen et al., 2020). Mastering an Army specialty demands routine memorization of procedures, a deep understanding of underlying principles, and the ability to apply them creatively in diverse situations. The current training approach falls short of providing the breadth and depth of knowledge needed to equip Soldiers for true mastery. This reduction in individual and collective readiness jeopardizes mission success and puts Soldier’s lives at unnecessary risk. Compounding the concerns about Soldier preparedness is the stark reality of wasted resources. The inefficiencies in the current training system drive costs without delivering the desired outcomes. These inefficiencies burden the budget and limit the Army’s ability to train all Soldiers effectively. AI offers a solution by streamlining administrative tasks, optimizing resource allocation, and dynamically generating and adapting training materials, potentially leading to significant cost savings (Bagchi et al., 2020). By leveraging AI’s capabilities, the Army can free up resources for other critical needs and ensure that every training dollar is invested in maximizing Soldier readiness. This financial hemorrhaging underscores the crucial need for transformative solutions. Embracing AI in training material development presents a powerful opportunity to enhance Soldier readiness and achieve significant cost savings through streamlined processes and adaptive learning techniques. Consequently, a compelling imperative emerges: to investigate the multifaceted pathways through which AI can be strategically harnessed to simultaneously elevate the operational effectiveness and optimize the fiscal solvency of military training.

These inefficiencies burden the budget and limit the Army’s ability to train all Soldiers effectively. AI offers a solution by streamlining administrative tasks, optimizing resource allocation, and dynamically generating and adapting training materials, potentially leading to significant cost savings (Bagchi et al., 2020). By leveraging AI’s capabilities, the Army can free up resources for other critical needs and ensure that every training dollar is invested in maximizing Soldier readiness. This financial hemorrhaging underscores the crucial need for transformative solutions. Embracing AI in training material development presents a powerful opportunity to enhance Soldier readiness and achieve significant cost savings through streamlined processes and adaptive learning techniques. Consequently, a compelling imperative emerges: to investigate the multifaceted pathways through which AI can be strategically harnessed to simultaneously elevate the operational effectiveness and optimize the fiscal solvency of military training. For course development, AI can streamline the creation of outlines, lesson plans, and supporting materials, significantly reducing development time (Bagchi et al., 2020). Human instructors remain crucial for validating AI-generated content and ensuring quality standards. The success of this pilot must be measured through specific metrics. These include a targeted 20% improvement in graduation rates across all four MOS pilot groups, a measurable increase in pass rates on MOS qualification exams, and a minimum of 33% reduction in course development time. Additionally, this plan should track the increase in instructor availability for individualized mentorship made possible by AI-driven efficiencies.

For course development, AI can streamline the creation of outlines, lesson plans, and supporting materials, significantly reducing development time (Bagchi et al., 2020). Human instructors remain crucial for validating AI-generated content and ensuring quality standards. The success of this pilot must be measured through specific metrics. These include a targeted 20% improvement in graduation rates across all four MOS pilot groups, a measurable increase in pass rates on MOS qualification exams, and a minimum of 33% reduction in course development time. Additionally, this plan should track the increase in instructor availability for individualized mentorship made possible by AI-driven efficiencies. management, while 11B Soldiers will train in virtual environments for squad tactics and leadership decision-making. Data from these pilot programs will guide the informed expansion of AI into other MOS areas and leadership development. AI will also play a crucial role in personalizing training within the pilot MOS groups. By analyzing performance data and tailoring instruction accordingly, AI will ensure that each Soldier receives the targeted training they need for maximum skill development (Chen et al., 2020). Pre- and post-AI implementation metrics will concretely demonstrate the gains in trainee competence. Without a meticulous strategic plan, this revolutionary technology risks having an unrealized potential.

management, while 11B Soldiers will train in virtual environments for squad tactics and leadership decision-making. Data from these pilot programs will guide the informed expansion of AI into other MOS areas and leadership development. AI will also play a crucial role in personalizing training within the pilot MOS groups. By analyzing performance data and tailoring instruction accordingly, AI will ensure that each Soldier receives the targeted training they need for maximum skill development (Chen et al., 2020). Pre- and post-AI implementation metrics will concretely demonstrate the gains in trainee competence. Without a meticulous strategic plan, this revolutionary technology risks having an unrealized potential. Weaving AI into the existing training fabric demands a carefully crafted strategic plan, a roadmap guiding this transformative technology’s seamless integration and ethical use. This plan must prioritize a responsible AI approach, guaranteeing ethical considerations while ensuring testing and employment are conducted in a controlled and safe manner (Department of Defense [DOD], 2022). The outcome: a future where AI seamlessly strengthens and complements human capabilities, empowering Soldiers with advanced skills and agility while upholding the highest ethical standards. This isn’t just about implementing software; it’s about crafting a future where technology elevates the battlefield prowess of every Soldier, ensuring both operational effectiveness and ethical responsibility.

Weaving AI into the existing training fabric demands a carefully crafted strategic plan, a roadmap guiding this transformative technology’s seamless integration and ethical use. This plan must prioritize a responsible AI approach, guaranteeing ethical considerations while ensuring testing and employment are conducted in a controlled and safe manner (Department of Defense [DOD], 2022). The outcome: a future where AI seamlessly strengthens and complements human capabilities, empowering Soldiers with advanced skills and agility while upholding the highest ethical standards. This isn’t just about implementing software; it’s about crafting a future where technology elevates the battlefield prowess of every Soldier, ensuring both operational effectiveness and ethical responsibility. The use of AI for military application is a contentious subject with many

The use of AI for military application is a contentious subject with many  Through the implantation of newly developed material, there would need to be some form of human interaction to ensure the validity of source material for AI systems to reference and the final approval of new blocks of information presented to Soldiers. Open communication and transparency would be crucial in dispelling anxieties and fostering a collaborative environment where AI is embraced as a powerful tool for enhancing Soldiers’ performance.

Through the implantation of newly developed material, there would need to be some form of human interaction to ensure the validity of source material for AI systems to reference and the final approval of new blocks of information presented to Soldiers. Open communication and transparency would be crucial in dispelling anxieties and fostering a collaborative environment where AI is embraced as a powerful tool for enhancing Soldiers’ performance. To maintain its edge in the digital era, the Army must integrate AI into Soldier training, forging a force equipped to excel on the modern battlefield. Embracing AI in training isn’t just a technological upgrade; it’s a strategic imperative for ensuring the continued success of the Army in the face of evolving threats. By integrating AI into MOS training and PME systems, the Army can equip its Soldiers with the adaptability, critical thinking, and technical skills demanded by the modern battlefield. Imagine immersive virtual boot camps that tailor training to individual strengths and weaknesses, honing combat skills in a risk-free environment. Envision personalized leadership development scenarios for Soldiers, where AI challenges them with complex ethical dilemmas and fosters strategic decision-making. This isn’t the future; it’s within reach through AI-powered training. By embracing this

To maintain its edge in the digital era, the Army must integrate AI into Soldier training, forging a force equipped to excel on the modern battlefield. Embracing AI in training isn’t just a technological upgrade; it’s a strategic imperative for ensuring the continued success of the Army in the face of evolving threats. By integrating AI into MOS training and PME systems, the Army can equip its Soldiers with the adaptability, critical thinking, and technical skills demanded by the modern battlefield. Imagine immersive virtual boot camps that tailor training to individual strengths and weaknesses, honing combat skills in a risk-free environment. Envision personalized leadership development scenarios for Soldiers, where AI challenges them with complex ethical dilemmas and fosters strategic decision-making. This isn’t the future; it’s within reach through AI-powered training. By embracing this  transformative shift, the Army can forge a generation of Soldiers who aren’t just technically proficient but also agile, adaptable, and ready to lead the way in the digital era. Incremental change won’t suffice. To dominate the digital battlefield, the Army must embrace AI and equip Soldiers to excel within it.

transformative shift, the Army can forge a generation of Soldiers who aren’t just technically proficient but also agile, adaptable, and ready to lead the way in the digital era. Incremental change won’t suffice. To dominate the digital battlefield, the Army must embrace AI and equip Soldiers to excel within it.

The Army is currently working to conceptualize the

The Army is currently working to conceptualize the  In the ETO, the largest contested deployment environment the Allies had to contend with was the Atlantic Ocean. Overcoming the threat was a huge challenge for the U.S. Navy and Britain’s Royal Navy. Convoy operations were an improvised response to defend merchant marine vessels against the German U-Boat threat. However, the convoy system was not adopted until the spring of 1941 — after millions of tons of supplies and thousands of merchant marine sailors had died during the initial stages of the Battle of the Atlantic.

In the ETO, the largest contested deployment environment the Allies had to contend with was the Atlantic Ocean. Overcoming the threat was a huge challenge for the U.S. Navy and Britain’s Royal Navy. Convoy operations were an improvised response to defend merchant marine vessels against the German U-Boat threat. However, the convoy system was not adopted until the spring of 1941 — after millions of tons of supplies and thousands of merchant marine sailors had died during the initial stages of the Battle of the Atlantic. The Allies conducted several non-permissive amphibious operations during the period 1942-1944 with Operation Overlord (D-Day) being the largest and arguably the most consequential one in the ETO. Overlord could never have been executed without the enormous staging area provided by the United Kingdom. Following two years of planning, even with the impact of the Mediterranean landings, the U.S. Army alone had assembled over 1.5 million Soldiers with 144,000 tons of supplies pre-loaded and an additional stockpile of 2.5 million tons of equipment for follow-on operations.

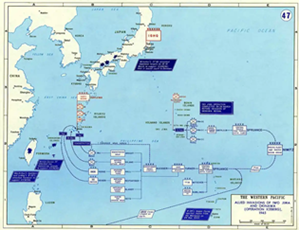

The Allies conducted several non-permissive amphibious operations during the period 1942-1944 with Operation Overlord (D-Day) being the largest and arguably the most consequential one in the ETO. Overlord could never have been executed without the enormous staging area provided by the United Kingdom. Following two years of planning, even with the impact of the Mediterranean landings, the U.S. Army alone had assembled over 1.5 million Soldiers with 144,000 tons of supplies pre-loaded and an additional stockpile of 2.5 million tons of equipment for follow-on operations. Marine divisions. Planning and coordination for the operation was extraordinary: “For the assault echelon alone, about 183,000 troops and 747,000 measurement tons of cargo were loaded into over 430 assault transports and landing ships at 11 different ports, from Seattle to Leyte, a distance of 6,000 miles.”

Marine divisions. Planning and coordination for the operation was extraordinary: “For the assault echelon alone, about 183,000 troops and 747,000 measurement tons of cargo were loaded into over 430 assault transports and landing ships at 11 different ports, from Seattle to Leyte, a distance of 6,000 miles.” Because of logistical considerations, the initial plan for the invasion of Okinawa called for the seizure of the southernmost Ryukyu Islands of Kerama and Keise nearby to establish base operations. This would facilitate the main invasion force by providing: “…a base for logistic support of fleet units, a protected anchorage, and a seaplane base.”

Because of logistical considerations, the initial plan for the invasion of Okinawa called for the seizure of the southernmost Ryukyu Islands of Kerama and Keise nearby to establish base operations. This would facilitate the main invasion force by providing: “…a base for logistic support of fleet units, a protected anchorage, and a seaplane base.” As might have been expected (in what will ring true today for planners), there was a significant shortfall of available sealift (for both strategic and littoral waters). The supply chain that resourced the Tenth Army stretched back to not only to South Pacific bases, but to the American West Coast. Strategic airlift, as it is recognized today, did not exist. Of note, mitigating lengthy supply lines had the invasion force taking a 30-day supply of rations, essential clothing and equipment, fuel, and medical and construction supplies.”

As might have been expected (in what will ring true today for planners), there was a significant shortfall of available sealift (for both strategic and littoral waters). The supply chain that resourced the Tenth Army stretched back to not only to South Pacific bases, but to the American West Coast. Strategic airlift, as it is recognized today, did not exist. Of note, mitigating lengthy supply lines had the invasion force taking a 30-day supply of rations, essential clothing and equipment, fuel, and medical and construction supplies.” or planners today, the ability to adequately forecast and requisition all classes of supplies, match them with available lift assets, and move them into theater should be a priority for combatant commands and supporting commands.

or planners today, the ability to adequately forecast and requisition all classes of supplies, match them with available lift assets, and move them into theater should be a priority for combatant commands and supporting commands. However, those same locations will likely be identified by aggressive nation states as “high value” targets with which to disrupt America’s ability to deploy into theater and subsequently sustain its forces. This same mindset also puts CONUS-based deployment and supply chain infrastructure at risk as the non-kinetic to kinetic threat stretches back to the homeland.

However, those same locations will likely be identified by aggressive nation states as “high value” targets with which to disrupt America’s ability to deploy into theater and subsequently sustain its forces. This same mindset also puts CONUS-based deployment and supply chain infrastructure at risk as the non-kinetic to kinetic threat stretches back to the homeland.

Planning today against China, our pacing threat — or worse, against adversarial collusion between members of the “Axis of Upheaval” — in a contested deployment environment will mean facing a variety of threats during the mobilization and movement process and beyond. Anything that would hinder or affect information networks (cyber) or physical infrastructure (sabotage) should be taken into consideration for force protection during the mobilization process. During the movement and RSOI processes, that interference will more likely be kinetic. The ability to adapt deployment processes to adjust to changing circumstances will also require creativity and command flexibility. While obvious changes as far as strategic airlift and information technology have added different dimensions to the deployment process, the need to overcome the tyranny of distance and time remains as critical today as it did in 1944 and 1945.

Planning today against China, our pacing threat — or worse, against adversarial collusion between members of the “Axis of Upheaval” — in a contested deployment environment will mean facing a variety of threats during the mobilization and movement process and beyond. Anything that would hinder or affect information networks (cyber) or physical infrastructure (sabotage) should be taken into consideration for force protection during the mobilization process. During the movement and RSOI processes, that interference will more likely be kinetic. The ability to adapt deployment processes to adjust to changing circumstances will also require creativity and command flexibility. While obvious changes as far as strategic airlift and information technology have added different dimensions to the deployment process, the need to overcome the tyranny of distance and time remains as critical today as it did in 1944 and 1945.

Dr. Billy Barry

Dr. Billy Barry deterministic, rule-bound models, Dr. Barry’s Hybrid Deterministic Generative AI (HDGAI) system rigorously enforces semantic validity, epistemic integrity, and ethical logic through structured token selection processes, preventing semantic drift and computational inaccuracies typical in traditional Gen AI. HDGAI is designed to be auditable, transparent, and free from “hallucinations” or unpredictable outputs, making it a more reliable tool for exploring the viability of courses of action and strategic decision-making.

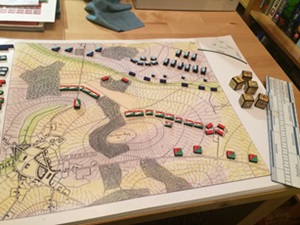

deterministic, rule-bound models, Dr. Barry’s Hybrid Deterministic Generative AI (HDGAI) system rigorously enforces semantic validity, epistemic integrity, and ethical logic through structured token selection processes, preventing semantic drift and computational inaccuracies typical in traditional Gen AI. HDGAI is designed to be auditable, transparent, and free from “hallucinations” or unpredictable outputs, making it a more reliable tool for exploring the viability of courses of action and strategic decision-making. with a computer or mobile device can access and play through these games. This accessibility democratizes wargaming and allows for wider participation, including the tool’s potential use in education and training.

with a computer or mobile device can access and play through these games. This accessibility democratizes wargaming and allows for wider participation, including the tool’s potential use in education and training. The ability to directly ask the system a clarifying question during gameplay – or modify the rules and structure – and receive clear explanations of outcomes enhanced players’ understanding and strategic thinking.

The ability to directly ask the system a clarifying question during gameplay – or modify the rules and structure – and receive clear explanations of outcomes enhanced players’ understanding and strategic thinking.

transparency, auditability, and reliability hold promise for other fields beyond a military context, such as intelligence analysis, threat assessment, legal fields, and education.

transparency, auditability, and reliability hold promise for other fields beyond a military context, such as intelligence analysis, threat assessment, legal fields, and education. Integrating an HDGAI approach to

Integrating an HDGAI approach to  and Army Futures Command (AFC) to bring the power of his HDGAI system to these commands’ respective mission sets.

and Army Futures Command (AFC) to bring the power of his HDGAI system to these commands’ respective mission sets.

Perhaps the most comprehensive multiple domain effort from any of Iran’s proxies remains Hamas’s

Perhaps the most comprehensive multiple domain effort from any of Iran’s proxies remains Hamas’s