[Editor’s Note: Every six months, Mad Scientist Laboratory recognizes its “Maddest” Guest Blogger. During the past six months, we’ve published a number of intriguing guest posts that have generated considerable interest and comments across our MadSci Community of Action (and beyond!). Selecting this period’s winner was a challenge, as we had a number of great guest blog post submissions. Runners up for “Maddest” Guest Blogger include:

-

- Cyborg Soldier 2050: Human/Machine Fusion and the Implications for the Future of the DOD, which synopsized the results of a year-long study published by the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Chemical Biological Center (CCDC CBC). Authors Peter Emanuel, Scott Walper, Diane DiEuliis, Natalie Klein, James B. Petro, and proclaimed Mad

Scientist James Giordano addressed the implications of transhumanism (i.e., machines being physically integrated with the human body to augment and enhance human performance) over the next 30 years and explored four potential military-use cases — this story was picked up and republished by a host of mainstream and on-line media outlets!

Scientist James Giordano addressed the implications of transhumanism (i.e., machines being physically integrated with the human body to augment and enhance human performance) over the next 30 years and explored four potential military-use cases — this story was picked up and republished by a host of mainstream and on-line media outlets! - A Scenario for a Hypothetical Private Nuclear Program, by Alexander Temerev (with commentary

by two Nuclear Subject Matter Experts who wished to remain anonymous) addressed the possible democratization and proliferation of nuclear weapons expertise by non-state actors and super-empowered individuals.

by two Nuclear Subject Matter Experts who wished to remain anonymous) addressed the possible democratization and proliferation of nuclear weapons expertise by non-state actors and super-empowered individuals.

- Cyborg Soldier 2050: Human/Machine Fusion and the Implications for the Future of the DOD, which synopsized the results of a year-long study published by the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Chemical Biological Center (CCDC CBC). Authors Peter Emanuel, Scott Walper, Diane DiEuliis, Natalie Klein, James B. Petro, and proclaimed Mad

In today’s post, we collectively recognize Mike Filanowski, Ruth Foutz, Sean McEwen, Mike Yocum, and Matt Ziemann (“Team RSM3” from the Army Futures Study Group Cohort VI in 2019) as our “Maddest” Guest Bloggers for the past six months — their Guns of August 2035 – “Ferdinand Visits the Kashmir”: A Future Strategic and Operational Environment masterfully blended storytelling with geo-political trends analysis to describe the events that morph a hypothetical limited Asian conflict into one that ultimately embroils the U.S. Army in Large Scale Combat Operations with a near-peer competitor — Enjoy!].

Prologue

“Drone swarm! Let’s go!” The sudden eerie whoop of the drone attack sirens urged LTC Mark Barnowski and his driver, SPC Pat Deeman, to hasten throwing their gear into their truck. The Indian Army units Barnowski was advising had fought well, but the Chinese with their vastly superior equipment had devastated them. Barnowski doubted his old infantry battalion in the 82nd Airborne Division would have fared much better against the Chinese drones, missiles, and exo-skeletoned soldiers helping Pakistan humiliate India.

“Drone swarm! Let’s go!” The sudden eerie whoop of the drone attack sirens urged LTC Mark Barnowski and his driver, SPC Pat Deeman, to hasten throwing their gear into their truck. The Indian Army units Barnowski was advising had fought well, but the Chinese with their vastly superior equipment had devastated them. Barnowski doubted his old infantry battalion in the 82nd Airborne Division would have fared much better against the Chinese drones, missiles, and exo-skeletoned soldiers helping Pakistan humiliate India.

Barnowski’s boss, BG McNewe, had recalled him to the American advisory base further south (to be evacuated?). Fortunately 20th Century landlines still worked — pretty much no other commo did. Barnowski said his goodbyes to his counterparts and headed south post-haste.

As Barnowski and Deeman sped out of the outpost, they were stunned anew by timeless scenes of military collapse. Piles of dead bodies mixed with rows of wounded soldiers waiting for help. As the sirens sounded, soldiers began to panic as officers struggled for control; all this blended with the indecipherable din and stench of war. Lines of soldiers intermixed with the occasional truck straggled out of the outpost, away from the advancing Chinese, silently, in utter defeat, staring thousands of yards ahead at nothing.

As the duo exited the wire, the unmistakable roar of American-supplied M2 .50 caliber machine guns took center stage as the Indians attempted resistance. Soldiers cheered as tracers arced not only toward the drones but also Chinese soldiers cresting the ridges outside the wire. The Chinese moved implausibly fast, but the angles of their exo-skeletons exposed them against the softer curves of the Himalayan foothills in Kashmir.

The Chinese sounded morale-boosting bugles and started firing. In response, the machine guns tore into them, sending up brown-dirt geysers tinted occasionally by red spray as armor piercing bullets ripped through exoskeletons into the soft humans beneath.

Barnowski and Deeman couldn’t resist a pause to enjoy the guns’ handiwork. Somewhat cheered, they exchanged grins. “It might be 2035, but some things never change.” “Yessss, ssssir!” “Now let’s get the #!@! out of here!” “Yes, sir!” Deeman accelerated the truck to join the flow heading south.

Introduction

How did Barnowski get there? In the 2030’s, America could battle a technologically and numerically superior adversary (China) per the U.S. Army’s current operating concept (U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) Pamphlet 525-3-1, The U.S. Army in Multi-Domain Operations 2028). Army officers and soldiers from the centennial generation could face another Asian land war as future leaders; this time against a more capable foe.

How did Barnowski get there? In the 2030’s, America could battle a technologically and numerically superior adversary (China) per the U.S. Army’s current operating concept (U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) Pamphlet 525-3-1, The U.S. Army in Multi-Domain Operations 2028). Army officers and soldiers from the centennial generation could face another Asian land war as future leaders; this time against a more capable foe.

But what will be the conflict’s nature? Where and how does our next war start? The U.S. Army’s Futures Studies Group (AFSG) spent over six months answering these questions using cutting-edge strategy analysis techniques.

This post highlights some of that analysis in the form of a future strategic and operational environment (FSOE). The FSOE found the most likely flashpoint for war with China involves Islamist militant havens in Pakistan. The Army could face combat there against numerically superior opponents with an asymmetric advantage in artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics.

This post highlights some of that analysis in the form of a future strategic and operational environment (FSOE). The FSOE found the most likely flashpoint for war with China involves Islamist militant havens in Pakistan. The Army could face combat there against numerically superior opponents with an asymmetric advantage in artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics.

Global power convergence among China, India, and America creates the conflict framework, in a world where China and America are superpowers, albeit in decline. America and China’s technologically advanced militaries are progressively drawn into a conflict with questionable strategic ends that strenuously tests the boundaries of “limited” war.

Students of history will recognize in this analysis past parallels, futurists will identify the collision of dominant trends, and technologists will see today’s emerging technologies realized in military application. These predictions rest on credible, cutting edge analytical techniques used by the best in the field, as the rest of this article describes.

Background

The AFSG developing this FSOE combined qualitative and quantitative analysis to reach its conclusions, combining this information with quantitative trend analysis models. Most notable of these was the International Futures (IFs) model from the Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures at the University of Denver. It uses hundreds of socio-economic-military variables to produce forecasts for 186 countries through 2100. The team assessed multiple IFs variables that propel significant change (for example, demography and energy) to identify global factors correlated to relevant change, such as increases in military or political power (“drivers”). The team then coupled drivers with qualitative information to identify actors with a stake in areas of interest. This analysis further enabled identification of likely future real world events (“signposts”) catalyzing driver change, thus generating the predicted future.

This analysis revealed the overarching importance of relative economic success between China and America in determining important global secondary factors,  such as political stability and military growth. Using this observation, the team narrowed its analysis to four alternative futures: strong Chinese/ strong American economy, strong Chinese /weak American economy, weak Chinese /strong American economy, and weak Chinese/weak American economy.

such as political stability and military growth. Using this observation, the team narrowed its analysis to four alternative futures: strong Chinese/ strong American economy, strong Chinese /weak American economy, weak Chinese /strong American economy, and weak Chinese/weak American economy.

In scenario four, the team noticed a convergence of global power among China, America, and India that hinted at conflict in an area (the Indo-Chinese border) rife with political tensions even today. However, what leads to declining American and Chinese economies in 2035?

Future Strategic Environment

America and China resolve their trade disputes before the end of President Trump’s first term, creating a mutually beneficial economic boom. Historically low energy prices follow Maduro’s overthrow in Venezuela, adding impetus to the boom.

The economic trends continue into President Trump’s second term, during which he negotiates for OPEC to include Russia and Kazakhstan (OPEC+) in an attempt to stabilize those countries. Meanwhile, China reaps huge monetary and military technological returns on robotics investments, mitigating its transition into a post-mature demography, an erstwhile drag on their economy. Technology investments are the only feasible economic escape from their demographic destiny.

The economic trends continue into President Trump’s second term, during which he negotiates for OPEC to include Russia and Kazakhstan (OPEC+) in an attempt to stabilize those countries. Meanwhile, China reaps huge monetary and military technological returns on robotics investments, mitigating its transition into a post-mature demography, an erstwhile drag on their economy. Technology investments are the only feasible economic escape from their demographic destiny.

Iran is left behind by global economic growth. Continued sanctions combined with the resurgence of a newly democratic Venezuela (inspiring oppressed Iranians) spark a civil war in Iran in 2025. President Pence, elected to continue President Trump’s economic policies, joins Xi Jinping in the UN Security Council to create a French-led UN task force to restore Iranian governance.

Disappointed by this acquiescence to the West, and following Xi’s “accidental” death, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) elects a hard-liner nationalist in 2028 to renegotiate terms for foreign investment and influence in a free Iran. As Iran becomes more democratic, foreign investment floods the country to exploit the world’s fourth-largest proven oil reserves and meet skyrocketing global energy demands. This renews Chinese and American economic competition.

Disappointed by this acquiescence to the West, and following Xi’s “accidental” death, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) elects a hard-liner nationalist in 2028 to renegotiate terms for foreign investment and influence in a free Iran. As Iran becomes more democratic, foreign investment floods the country to exploit the world’s fourth-largest proven oil reserves and meet skyrocketing global energy demands. This renews Chinese and American economic competition.

Although an aged Vladimir Putin is “retired” from public life at this point, he is still Russia’s power broker. Joining OPEC+ was step one in a long play to disintegrate OPEC and establish Russian oil market dominance. America’s decision to curb shale and green-energy investments has only strengthened world dependence on OPEC oil.

Sensing the opportunity in Iran to drive a wedge between the US and China, Russian global gray zone warfare intercedes to disintegrate OPEC+ during the 2029-2033 domestically-focused US presidential term. Attempting to survive the fallout of social security default and renewed anger on U.S. dependence on foreign oil, the U.S. Congress passes “NOPEC” legislation. OPEC+ is thus rendered ineffectual if not outright disbanded.

The oil market becomes hyper-volatile without the predictability of OPEC+ market strategies. America turns inward to jumpstart shale production but suffers delays due to the limited availability of an experienced workforce.

China’s Eurasian land bridge through Kazakhstan remains strongly subject to Russian influence and China shifts focus to transporting oil through the Chinese-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Renewed competition and missed gross domestic product projections between China and America ushers in renewed tariffs and competition for expensive oil.

China also must deal with internal discord. Although the CCP has retained control of the country, the Chinese middle class, temporarily placated by the growth of robots, economic boom, and global peace, pressures the CCP anew to deliver the “China Dream” during a slowing economy.

Historically-high levels of ethnically Han dissent on the Chinese coast lead the Han to coordinate with inland ethnic groups to oppose the CCP due to its slowness on delivering the dream. A younger faction of the weakest-ever CCP seeks military action to drive nationalist party support. In early 2035, they succeed in replacing the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) leader with a nationalist hard-liner.

Meanwhile, India is able to engage in “realpolitik” with all the key global players and benefit from the advantages each offers. This, coupled with its younger demographic profile, excellent education system, and access to technology, allows it to converge into almost near-peer status with the two dominant powers.

Future Operational Environment

This strategic environment enables a 2035 operational environment possessing clear continuities and contrasts with the past. An emergent India, combined with a declining China and U.S., sets the stage for a conflict between America and China during an escalating war between India and Pakistan.

This strategic environment enables a 2035 operational environment possessing clear continuities and contrasts with the past. An emergent India, combined with a declining China and U.S., sets the stage for a conflict between America and China during an escalating war between India and Pakistan.

This conflict’s hallmark is the tendency of limited wars to escalate; a clear continuity with historical precedent. The primary contrast between history and the proposed operational environment is the incorporation of AI and robotic technology into conventional ground combat.

Reopening a 20th Century wound, an Islamic extremist terrorist attack in Kashmir in 2035 sparks conflict. The assassination of India’s Kashmir governor by Pakistan-based Islamic terrorists in the summer results in a massive military response. The Indian Army dismantles terrorist networks on Indian Territory in the Northwest.

Simultaneously, Indian Special Forces raid terrorist support zones across the international border into Pakistan’s portion of the Chenab River Valley. The Indian Army rapidly achieves its limited objectives and initiates a ceasefire, but the Pakistan government, sensing their poor negotiating position, escalates by involving their regional benefactor, China.

China has multiple reasons for involvement. A Pakistani alliance allows them to support a key regional partner and safeguard their economic investment in CPEC. A successful limited war with India would cement them as the regional hegemon. Finally, the Chinese have the “justification” to seize historically important territory, helping fulfill the Chinese Dream by 2050. China is thus compelled to intervene.

Chinese intrusion quickly escalates the conflict in unanticipated ways. China initiates a joint navy/air force strike, including cyber-attacks, to neutralize the Indian strategic nuclear deterrent. Chinese space forces disrupt Indian telecommunication, resulting in widespread confusion and panic in the Indian government.

Chinese intrusion quickly escalates the conflict in unanticipated ways. China initiates a joint navy/air force strike, including cyber-attacks, to neutralize the Indian strategic nuclear deterrent. Chinese space forces disrupt Indian telecommunication, resulting in widespread confusion and panic in the Indian government.

In response, the Indian Prime Minister orders the mobilization of the northern army, but poor communication cripples this effort. The Chinese see the mobilization as an escalation and begin mobilizing the PLA along their southern border. Effective communication and a thoroughly professionalized military force allows the PLA to mobilize in days while the Indian Army struggles just to move. The Chinese justify their subsequent attack into Indian-controlled territory as pre-emption of India’s mobilization.

The Chinese offensive in August 2035 routs the Indian Army and demonstrates a major leap forward in their military technology. Chinese soldiers enjoy equipment augmented with AI and robotics advances gleaned from industry. PLA forces equipped with robotic exoskeletons move rapidly through previously denied mountainous terrain. Their newfound mobility allows the PLA to flank Indian defenses and destroy them with AI-controlled drones and missiles.

The Indian Army collapses and retreats south in the face of the Chinese “blitz”. The Chinese attack seizes the disputed border areas and shocks the Indian Army a la the German 1940 offensive. However, the stunning success of China’s technology leads to further escalation.

The Indian people blame their government for the defeat and the Indian Army’s lack of preparedness due to their antiquated 20th century strategies and technologies. They subsequently threaten to replace India’s democratic government with a military dictatorship.

The Indian government reacts decisively to save the remaining Indian forces and demonstrate their resolve. India’s Prime Minister accepts a proposed plan to employ remaining tactical nuclear weapons on an isolated portion of the Chinese forces.

India then plays their trump card and delivers an ultimatum to the country with which it has built increasingly close military ties, America: enter the conflict or risk nuclear war. America again faces inexorable entry into yet another “limited conflict” in Asia that threatens to spin out of control.

Conclusion

Who knows if all this will occur as described? However, everything presented here is well grounded in known facts and credible forecasts.

Regardless, over the next 16 years it seems likely ground combat will remain the primary means with which warring entities will exert their will on each other. Furthermore, mobility, protection, and firepower will remain the foundations of ground combat. Technological advances will alter methods but technology can’t alter these fundamental concepts of ground combat success.

In all those regards, history will more than likely “rhyme with itself” in yet another conflict on China’s periphery. Finally, “limited” war will remain politically irresistible, but as warfighters have known immutably since at least Clausewitz’s time, they unleash relentless momentum toward “unlimited” war.

Epilogue

Barnowski reported immediately upon arriving at the American advisory base. He was barely in the general’s office before BG McNewe barked at him without looking up from his work. “Where in the hell have you been?” Barnowski contemplated relating the hell he had seen, but thought better of it.

“Unpack your bags, you’re my new three.” “Sir?” “Are you deaf AND slow? I said unpack your bags, you’re my new three.” Still no response, so McNewe looked  up. “I said unpack, you’re my new ops guy. The advisory team is now responsible for setting up a joint reception and staging area. The ready brigade arrives tomorrow. Looks like we’re in it for the long haul.”

up. “I said unpack, you’re my new ops guy. The advisory team is now responsible for setting up a joint reception and staging area. The ready brigade arrives tomorrow. Looks like we’re in it for the long haul.”

Barnowski turned to go but BG McNewe locked eyes with him. “Mark, we’ve got a lot to do….but I know you’re up to it…..let’s get after it!”

If you enjoyed this post, check out these previous “Maddest” Guest Bloggers:

-

- Robert J. Hranek’s The Otso Incident with Donovia in 2030

- Dr. Alexander Kott‘s Ground Warfare in 2050: How It Might Look

- Sam Bendett‘s Russian Ground Battlefield Robots: A Candid Evaluation and Ways Forward

- Pat Filbert‘s Why do I have to go first?!

Mike Filanowski is an Infantry Officer assigned to Headquarters Department of the Army G3. Ruth Foutz is an Army Public Health Center Safety and Occupational Health Manager assigned to Army Futures Command Headquarters. Sean McEwen is an Artillery Officer assigned to the U.S. Army Research Laboratory. Mike Yocum is a supervisory Operations Research/Systems Analyst assigned to the U.S. Army Manpower Analysis Agency, and Matt Ziemann is a physicist assigned to the U.S. Army Research Laboratory. Collectively, they are “Team RSM3”, one of the teams that completed a 6-month developmental assignment with Army Futures Study Group Cohort VI in 2019.

Disclaimer: The views and analysis expressed in this article are solely their own and do not represent those of the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), Army Futures Command (AFC), the U.S. Army, the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Government, or the Pardee Center for International Studies at the University of Denver.

be the future of warfare. Near-peer competitors will seek to achieve national objectives through competition

be the future of warfare. Near-peer competitors will seek to achieve national objectives through competition but not necessarily cyclical. Potential adversaries will seek to achieve their national interest short of conflict and will use a range of actions from cyber to kinetic against unmanned systems walking up to the line of a short or protracted armed conflict. Authoritarian regimes are able to more easily ensure unity of effort and whole-of-government over Western democracies and work to exploit fractures and gaps in decision-making, governance, and policy.

but not necessarily cyclical. Potential adversaries will seek to achieve their national interest short of conflict and will use a range of actions from cyber to kinetic against unmanned systems walking up to the line of a short or protracted armed conflict. Authoritarian regimes are able to more easily ensure unity of effort and whole-of-government over Western democracies and work to exploit fractures and gaps in decision-making, governance, and policy. and

and substantial nuclear arsenals, as does the United States, which will continue to make Great Power conventional warfare a high risk / high cost endeavor. The availability of non-nuclear capabilities that can deliver regional and global effects is a new attribute of the OE. This further complicates the deterrence value of militaries and the escalation theory behind flexible deterrent options. The inherent implications of cyber effects in the real world – especially in economies, government functions, and essential services – further exacerbates the blurring between competition and conflict.

substantial nuclear arsenals, as does the United States, which will continue to make Great Power conventional warfare a high risk / high cost endeavor. The availability of non-nuclear capabilities that can deliver regional and global effects is a new attribute of the OE. This further complicates the deterrence value of militaries and the escalation theory behind flexible deterrent options. The inherent implications of cyber effects in the real world – especially in economies, government functions, and essential services – further exacerbates the blurring between competition and conflict. primary focus on challenging the U.S. Army all the way from its home station installations (i.e., the Strategic Support Area) to the Close Area fight. We can expect cyber attacks against critical infrastructure, the use of

primary focus on challenging the U.S. Army all the way from its home station installations (i.e., the Strategic Support Area) to the Close Area fight. We can expect cyber attacks against critical infrastructure, the use of  subsequently attrited. In LSCO with a near-peer competitor, the ability to reconstitute will be imperative. The Army (and larger DoD) may need to shift away from large and expensive systems to

subsequently attrited. In LSCO with a near-peer competitor, the ability to reconstitute will be imperative. The Army (and larger DoD) may need to shift away from large and expensive systems to remain constrained by “human-on-the-loop” or “human-in-the-loop” constructs when our adversaries are unlikely to similarly restrict their own autonomous warfighting capabilities. Further, the employment of this approach could impact the Army’s MDO strategy. The effects of “human-starts-the-loop” on the kill chain – shortening, flattening, or otherwise dispersing – would necessitate changes in force structuring that could maximize resource allocation in personnel, platforms, and materiel. This scenario presents the Army with an opportunity to execute MDO successfully with increased cost savings, by: 1) Conducting independent maneuver – more agile and streamlined units moving rapidly; 2) Employing cross-domain fires – efficiency and speed in targeting and execution; 3) Maximizing human potential – putting capable Warfighters in optimal positions; and 4) Fielding in echelons above brigade – flattening command structures and increasing efficiency.

remain constrained by “human-on-the-loop” or “human-in-the-loop” constructs when our adversaries are unlikely to similarly restrict their own autonomous warfighting capabilities. Further, the employment of this approach could impact the Army’s MDO strategy. The effects of “human-starts-the-loop” on the kill chain – shortening, flattening, or otherwise dispersing – would necessitate changes in force structuring that could maximize resource allocation in personnel, platforms, and materiel. This scenario presents the Army with an opportunity to execute MDO successfully with increased cost savings, by: 1) Conducting independent maneuver – more agile and streamlined units moving rapidly; 2) Employing cross-domain fires – efficiency and speed in targeting and execution; 3) Maximizing human potential – putting capable Warfighters in optimal positions; and 4) Fielding in echelons above brigade – flattening command structures and increasing efficiency. China now has Combat Training Centers.

China now has Combat Training Centers.

mirror imaging. The Mad Scientist Laboratory offers it as a platform for the contrarians in our network to share their alternative perspectives and analyses regarding the Operational Environment (OE). We continue our series of “Tenth Man” posts examining the foundational assumptions of

mirror imaging. The Mad Scientist Laboratory offers it as a platform for the contrarians in our network to share their alternative perspectives and analyses regarding the Operational Environment (OE). We continue our series of “Tenth Man” posts examining the foundational assumptions of The character of warfare will change in the future OE as it inexorably has since the advent of flint hand axes; iron blades; stirrups; longbows; gunpowder; breech loading, rifled, and automatic guns; mechanized armor; precision-guided munitions; and the Internet of Things. Speed, automation, extended ranges,

The character of warfare will change in the future OE as it inexorably has since the advent of flint hand axes; iron blades; stirrups; longbows; gunpowder; breech loading, rifled, and automatic guns; mechanized armor; precision-guided munitions; and the Internet of Things. Speed, automation, extended ranges,  broad and narrow weapons effects, and increasingly integrated multi-domain conduct, in addition to the complexity of the terrain and social structures in which it occurs, will make mid Twenty-first Century warfare both familiar and utterly alien.

broad and narrow weapons effects, and increasingly integrated multi-domain conduct, in addition to the complexity of the terrain and social structures in which it occurs, will make mid Twenty-first Century warfare both familiar and utterly alien. assumes that humans will remain central to the rationale for war and its most essential elements of execution. The nature of war has remained relatively constant from Thucydides through Clausewitz, and forward to the present. War is still waged because of fear, honor, and interest, and remains an expression of politics by other means. While machines are becoming ever more prevalent across the battlefield – C5ISR, maneuver, and logistics – we cling to the belief that parties will still go to war over human interests; that war will be decided, executed, and controlled by humans.

assumes that humans will remain central to the rationale for war and its most essential elements of execution. The nature of war has remained relatively constant from Thucydides through Clausewitz, and forward to the present. War is still waged because of fear, honor, and interest, and remains an expression of politics by other means. While machines are becoming ever more prevalent across the battlefield – C5ISR, maneuver, and logistics – we cling to the belief that parties will still go to war over human interests; that war will be decided, executed, and controlled by humans. Imagine that a machine recognizes a strategic opportunity or impetus to engage a nation-state actor that is conventionally (read that humanly) viewed as weak or in a presumed disadvantaged state. The machine launches offensive operations to achieve a favorable outcome or objective that it deemed too advantageous to pass up.

Imagine that a machine recognizes a strategic opportunity or impetus to engage a nation-state actor that is conventionally (read that humanly) viewed as weak or in a presumed disadvantaged state. The machine launches offensive operations to achieve a favorable outcome or objective that it deemed too advantageous to pass up. influence may not be conducive to victory. Victory may be simply a calculated or algorithmic outcome that causes an adversary’s machine to decide their own victory is unattainable.

influence may not be conducive to victory. Victory may be simply a calculated or algorithmic outcome that causes an adversary’s machine to decide their own victory is unattainable. – How much and how should the Army recruit and cultivate human talent if war is no longer human-centric?

– How much and how should the Army recruit and cultivate human talent if war is no longer human-centric? – Should the U.S. military divest from platforms and materiel solutions (hardware) and re-focus on becoming algorithmically and digitally-centric (software)?

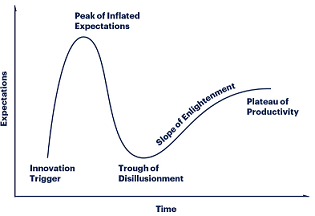

– Should the U.S. military divest from platforms and materiel solutions (hardware) and re-focus on becoming algorithmically and digitally-centric (software)? – Technology advances to the point of near or actual machine sentience, with commensurate machine speed accelerating the potential for escalated competition and armed conflict beyond transparency and human comprehension.

– Technology advances to the point of near or actual machine sentience, with commensurate machine speed accelerating the potential for escalated competition and armed conflict beyond transparency and human comprehension. – Smaller, less-capable states or actors begin achieving surprising or unexpected victories in warfare.

– Smaller, less-capable states or actors begin achieving surprising or unexpected victories in warfare.

6. “

6. “