[Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist Laboratory is pleased to publish today’s post by guest blogger Kat Cassedy, who continues to explore how the current COVID-19 Global Pandemic could shape the Operational Environment (OE) and change the character of warfare. What does this seismic shift portend for the future of the Army? Read on!]

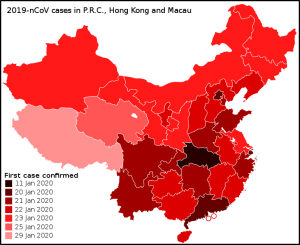

The corona virus pandemic of 2020 seemed to come out of nowhere. Right around the turn of the year, news stories started to percolate out from China into the West’s consciousness, and each week after that, the bubbling got louder. By mid-February, it was clear the virus was not going to stay put in China, and by the end of February, COVID-19 began its assault on Western Europe and North America. As of this writing, just over two weeks have passed since America started taking serious steps at the national level, beginning with declaring a national emergency, and halting flights coming from most of Western Europe, the new epicenter for the outbreak. Last weekend, several U.S. cities and states where the infection rate has climbed fastest issued official stay-at-home orders, after first moving public education to distance learning only, calling for a halt to gatherings of more than 10 people, and closing or restricting to take-out the nation’s restaurant industry.

Throughout this fast-moving pandemic, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) has taken steps to protect its forces, generally enacting protective measures proactively to reduce spread as well as infection with the force. Units deployed in regions hit first began self-isolation and preventative hand washing and disinfection protocols early on, and the chain of command took establishing social distancing measures to heart. These actions likely helped limit the spread of COVID-19 within the US military ranks, which is excellent news.

What is also becoming rapidly clear, however, is that the drastic actions taken across the globe to halt or slow this pandemic’s spread (at least the first wave of it) to buy time for healthcare systems to treat current victims while others work to identify a vaccine or cure will have long-lasting effects on business, society, and government everywhere. Particularly concerning are the still-emerging economic impacts (some economists estimate as much as $3 trillion in losses globally1, with a likely extended recession) of suspending large swathes of the global business environment, with hundreds of millions of people out of work or shifted to telework for extended periods.

What is also becoming rapidly clear, however, is that the drastic actions taken across the globe to halt or slow this pandemic’s spread (at least the first wave of it) to buy time for healthcare systems to treat current victims while others work to identify a vaccine or cure will have long-lasting effects on business, society, and government everywhere. Particularly concerning are the still-emerging economic impacts (some economists estimate as much as $3 trillion in losses globally1, with a likely extended recession) of suspending large swathes of the global business environment, with hundreds of millions of people out of work or shifted to telework for extended periods.

The genie is out of the bottle. When the world emerges from this pandemic, countless systems, processes, and structures once thought immutable will either  be eliminated or permanently transformed to adapt to the realities of a post-pandemic world. The DoD broadly and the U.S. Army in specific are no exceptions to these anticipated sweeping changes. Accordingly, what are some of the significant changes we can foresee, and how should the Army prepare for those changes in what’s likely to be an extremely constrained fiscal environment?

be eliminated or permanently transformed to adapt to the realities of a post-pandemic world. The DoD broadly and the U.S. Army in specific are no exceptions to these anticipated sweeping changes. Accordingly, what are some of the significant changes we can foresee, and how should the Army prepare for those changes in what’s likely to be an extremely constrained fiscal environment?

The first and most obvious change is likely to come in the technology area, specifically in the ability to maintain continuity of operations in a virtual environment. With a globally distributed workforce of over a million uniformed and civilian personnel, telework is not a new concept to the Army. Coordination between bases and facilities around the world is a daily routine. That said, there are concentrations of personnel in key physical locations who in this pandemic have shifted completely to telework, and they are likely to remain in that state for the coming weeks or months. When the next round of Congressional budget setting comes,  will there be increased pressure to eliminate most or all Army office buildings if there is a demonstrated track record of successful virtual operations? What effect will that have on the Warfighter, if much or all of their support infrastructure moves to telework? Will it improve operational security by dispersing these functions geographically across the country? Will it free high dollar real estate holdings/expenses to shift to other budget needs?

will there be increased pressure to eliminate most or all Army office buildings if there is a demonstrated track record of successful virtual operations? What effect will that have on the Warfighter, if much or all of their support infrastructure moves to telework? Will it improve operational security by dispersing these functions geographically across the country? Will it free high dollar real estate holdings/expenses to shift to other budget needs?

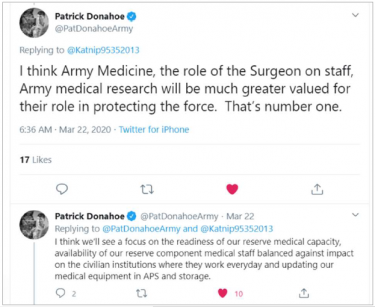

Another area for emphasis for the post-Pandemic age will be in the role of medical officers and medical readiness in the military chain of command. Last weekend, via Twitter, I asked MG Patrick Donahoe, Deputy Commanding General, Operations, 8th Army, what sacred cows he thought would fall or change as we emerge from the pandemic. In his tweeted response, he offered the thoughts in the accompanying screen shot (shared above with his permission).

Another area for emphasis for the post-Pandemic age will be in the role of medical officers and medical readiness in the military chain of command. Last weekend, via Twitter, I asked MG Patrick Donahoe, Deputy Commanding General, Operations, 8th Army, what sacred cows he thought would fall or change as we emerge from the pandemic. In his tweeted response, he offered the thoughts in the accompanying screen shot (shared above with his permission).  We later agreed this can be summarized as increasing the role and awareness of medical readiness to the strategic level, not relegating it to tactical/operational levels. Given the lengths to which civilian and military medical personnel – some who split their time between civil and military duties – are responding to the pandemic, it is safe to assume that this occupational specialty family will have significantly increased demands and expectations in the future, with attendant additional resourcing requirements.

We later agreed this can be summarized as increasing the role and awareness of medical readiness to the strategic level, not relegating it to tactical/operational levels. Given the lengths to which civilian and military medical personnel – some who split their time between civil and military duties – are responding to the pandemic, it is safe to assume that this occupational specialty family will have significantly increased demands and expectations in the future, with attendant additional resourcing requirements.

The increasingly strategic nature of medicine and medical readiness in warfighting comes with some new tactical and operational concerns, however. If this pandemic proves to be recurring for an extended period, touching critical areas of concern in every GCC AOR, what is going to happen when Soldiers – conventional or SOF – need to deploy into pandemic hot zones in the coming days, weeks, and months? Are they going to be issued PPE before deploying? Will they be trained in how to use it? By whom? Especially when all medical personnel are likely to be severely overtaxed for the foreseeable future, simply responding to the pandemic itself?

How about those Army personnel conducting clandestine operations? Not all those activities can be moved to cyberspace, for a variety of reasons. How will social distancing alter the operational tradecraft of the clandestine services? If PPE is socio-culturally appropriate, are there differences in type/brand/usage that need to be factored in?

And how might the pandemic change the very nature of where the Army fights, going forward? For much of the past two decades, strategic planners have increasingly based assumptions about future operating environments on the likelihood of more fighting occurring in urban mega-city environments, and have shaped doctrine, resource development, and leadership thinking heavily in that direction.

And how might the pandemic change the very nature of where the Army fights, going forward? For much of the past two decades, strategic planners have increasingly based assumptions about future operating environments on the likelihood of more fighting occurring in urban mega-city environments, and have shaped doctrine, resource development, and leadership thinking heavily in that direction.

What if the pandemic has the opposite effect? There is already an emerging school of thought that populations may actually begin dispersing, moving away from dense population centers and their higher risk of infection and accompanying general decline in quality of life.2 If this comes to pass, will the Army need to again refocus Warfighter development, shifting to smaller, more geographically dispersed, and mobile teams?

Finally, will this pandemic be the black swan event that fundamentally shifts DoD thinking about what “war” looks like, writ large? With increased concern and focus on operations in the “gray zone,” or “competition below armed conflict,” will the corona virus effectively put a halt to conventional force-on-force conflict, since such contact would exponentially increase the likelihood of mutually assured destruction — not by weapons, but by disease transmitted in the heat of battle?

Finally, will this pandemic be the black swan event that fundamentally shifts DoD thinking about what “war” looks like, writ large? With increased concern and focus on operations in the “gray zone,” or “competition below armed conflict,” will the corona virus effectively put a halt to conventional force-on-force conflict, since such contact would exponentially increase the likelihood of mutually assured destruction — not by weapons, but by disease transmitted in the heat of battle?

It may be too early at this point to be able to field reasonable solutions to most of these questions, particularly since there will likely be more variables to factor in as time passes and the world adjusts. Rather, this submission is meant to provoke new lines of thought and inquiry that Army and DoD leaders may consider exploring now, so as to best position the US military for significant, large scale change. Perhaps the most effective way to start working towards that planning is to incorporate some / all of the above possible futures and outcomes into scenarios for pending wargames and exercises, with the scenario development input of multi-disciplinary experts in competition / conflict below the kinetic threshold. That approach could allow senior leadership to test different approaches in a controlled and familiar environment now, to prepare for the near future.

But for now, please stay home, wash your hands, and live to fight another day!

If you enjoyed this post, check out Chris Elles‘ post, Contagion: COVID-19’s impact on the Operational Environment (Part 1)…

… share your thoughts on how #COVID19 is going to affect society / the idea of privacy / security @ArmyMadSci...

… and review our writing prompt and submit a blog post telling us how the on-going COVID-19 Global Pandemic could shape the OE and change the character of warfare. We look forward to reading and posting the most insightful submissions as future “Contagion” posts!

Kat Cassedy is a career OSINT professional focused on national security issues and specializing in developing practical solutions to unconventional and emerging threats across 21st century problem sets. She is a Senior Consultant to Helios Global Inc., supporting commercial and government clients in identifying, analyzing, and addressing high risk, high visibility, enterprise risk challenges. Kat tweets as @Katnip95352013.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or the Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

1 https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2020-coronavirus-pandemic-global-economic-risk/

2 Kotkin, Joel, “The Coming Age of Dispersion,” Quillette. March 25, 2020. https://quillette.com/2020/03/25/the-coming-age-of-dispersion/

In this latest episode of “The Convergence,” we talk to

In this latest episode of “The Convergence,” we talk to

Scientist James Giordano addressed the implications of transhumanism (i.e., machines being physically integrated with the human body to augment and enhance human performance) over the next 30 years and explored four potential military-use cases — this story was picked up and republished by a host of

Scientist James Giordano addressed the implications of transhumanism (i.e., machines being physically integrated with the human body to augment and enhance human performance) over the next 30 years and explored four potential military-use cases — this story was picked up and republished by a host of by two Nuclear Subject Matter Experts who wished to remain anonymous) addressed the possible democratization and proliferation of nuclear weapons expertise by non-state actors and super-empowered individuals.

by two Nuclear Subject Matter Experts who wished to remain anonymous) addressed the possible democratization and proliferation of nuclear weapons expertise by non-state actors and super-empowered individuals.

“Drone swarm! Let’s go!” The sudden eerie whoop of the drone attack sirens urged LTC Mark Barnowski and his driver, SPC Pat Deeman, to hasten throwing their gear into their truck. The Indian Army units Barnowski was advising had fought well, but the Chinese with their vastly superior equipment had devastated them. Barnowski doubted his old infantry battalion in the 82nd Airborne Division would have fared much better against the Chinese drones, missiles, and exo-skeletoned soldiers helping Pakistan humiliate India.

“Drone swarm! Let’s go!” The sudden eerie whoop of the drone attack sirens urged LTC Mark Barnowski and his driver, SPC Pat Deeman, to hasten throwing their gear into their truck. The Indian Army units Barnowski was advising had fought well, but the Chinese with their vastly superior equipment had devastated them. Barnowski doubted his old infantry battalion in the 82nd Airborne Division would have fared much better against the Chinese drones, missiles, and exo-skeletoned soldiers helping Pakistan humiliate India.

How did Barnowski get there? In the 2030’s, America could battle a technologically and numerically superior adversary (China) per the U.S. Army’s current operating concept (

How did Barnowski get there? In the 2030’s, America could battle a technologically and numerically superior adversary (China) per the U.S. Army’s current operating concept ( This post highlights some of that analysis in the form of a future strategic and operational environment (FSOE). The FSOE found the most likely flashpoint for war with China involves Islamist militant havens in Pakistan. The Army could face combat there against numerically superior opponents with an asymmetric advantage in artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics.

This post highlights some of that analysis in the form of a future strategic and operational environment (FSOE). The FSOE found the most likely flashpoint for war with China involves Islamist militant havens in Pakistan. The Army could face combat there against numerically superior opponents with an asymmetric advantage in artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics. such as political stability and military growth. Using this observation, the team narrowed its analysis to four alternative futures: strong Chinese/ strong American economy, strong Chinese /weak American economy, weak Chinese /strong American economy, and weak Chinese/weak American economy.

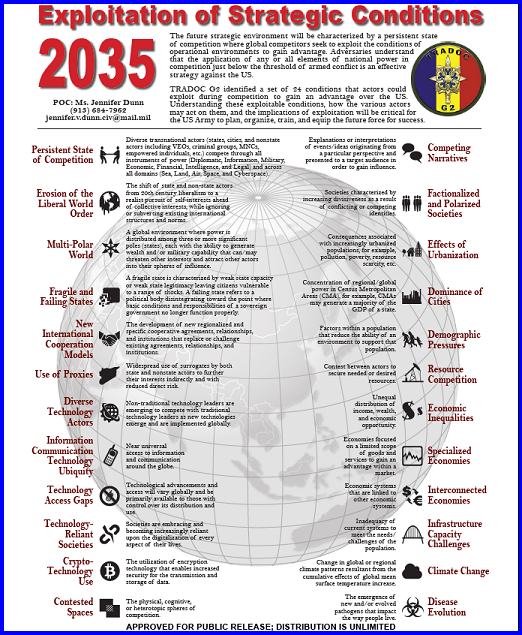

such as political stability and military growth. Using this observation, the team narrowed its analysis to four alternative futures: strong Chinese/ strong American economy, strong Chinese /weak American economy, weak Chinese /strong American economy, and weak Chinese/weak American economy. The economic trends continue into President Trump’s second term, during which he negotiates for OPEC to include Russia and Kazakhstan (OPEC+) in an attempt to stabilize those countries. Meanwhile, China reaps huge monetary and military technological returns on robotics investments, mitigating its transition into a post-mature demography, an erstwhile drag on their economy. Technology investments are the only feasible economic escape from their demographic destiny.

The economic trends continue into President Trump’s second term, during which he negotiates for OPEC to include Russia and Kazakhstan (OPEC+) in an attempt to stabilize those countries. Meanwhile, China reaps huge monetary and military technological returns on robotics investments, mitigating its transition into a post-mature demography, an erstwhile drag on their economy. Technology investments are the only feasible economic escape from their demographic destiny. Disappointed by this acquiescence to the West, and following Xi’s “accidental” death, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) elects a hard-liner nationalist in 2028 to renegotiate terms for foreign investment and influence in a free Iran. As Iran becomes more democratic, foreign investment floods the country to exploit the world’s fourth-largest proven oil reserves and meet skyrocketing global energy demands. This renews Chinese and American economic competition.

Disappointed by this acquiescence to the West, and following Xi’s “accidental” death, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) elects a hard-liner nationalist in 2028 to renegotiate terms for foreign investment and influence in a free Iran. As Iran becomes more democratic, foreign investment floods the country to exploit the world’s fourth-largest proven oil reserves and meet skyrocketing global energy demands. This renews Chinese and American economic competition.

This strategic environment enables a 2035 operational environment possessing clear continuities and contrasts with the past. An emergent India, combined with a declining China and U.S., sets the stage for a conflict between America and China during an escalating war between India and Pakistan.

This strategic environment enables a 2035 operational environment possessing clear continuities and contrasts with the past. An emergent India, combined with a declining China and U.S., sets the stage for a conflict between America and China during an escalating war between India and Pakistan. Chinese intrusion quickly escalates the conflict in unanticipated ways. China initiates a joint navy/air force strike, including cyber-attacks, to neutralize the Indian strategic nuclear deterrent. Chinese space forces disrupt Indian telecommunication, resulting in widespread confusion and panic in the Indian government.

Chinese intrusion quickly escalates the conflict in unanticipated ways. China initiates a joint navy/air force strike, including cyber-attacks, to neutralize the Indian strategic nuclear deterrent. Chinese space forces disrupt Indian telecommunication, resulting in widespread confusion and panic in the Indian government.

up. “I said unpack, you’re my new ops guy. The advisory team is now responsible for setting up a joint reception and staging area. The ready brigade arrives tomorrow. Looks like we’re in it for the long haul.”

up. “I said unpack, you’re my new ops guy. The advisory team is now responsible for setting up a joint reception and staging area. The ready brigade arrives tomorrow. Looks like we’re in it for the long haul.”

U.S. Army all the way from our home station installations (i.e., the Strategic Support Area) to the Close Area fight. We can expect cyber attacks against critical infrastructure, the use of

U.S. Army all the way from our home station installations (i.e., the Strategic Support Area) to the Close Area fight. We can expect cyber attacks against critical infrastructure, the use of  Russian cyber operations coordinated attacks against Ukrainian artillery, in just one

Russian cyber operations coordinated attacks against Ukrainian artillery, in just one by another spoofed message to the original phone. With a high number of messages to enough targets, an artillery strike is called in on the area where an excess of cellphone usage has been detected. To translate into plain English, Russia has successfully combined traditional weapons of land warfare (such as artillery) with the new potential of cyber warfare.

by another spoofed message to the original phone. With a high number of messages to enough targets, an artillery strike is called in on the area where an excess of cellphone usage has been detected. To translate into plain English, Russia has successfully combined traditional weapons of land warfare (such as artillery) with the new potential of cyber warfare. and its allies have held for the past several decades. Highlighting this importance, Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2017 stated that “whoever becomes the leader in this sphere will become the ruler of the world.” AI-guided IO tools can empathize with an audience to say anything, in any way needed, to change the perceptions that drive those physical weapons. Future IO systems will be able to individually monitor and affect

and its allies have held for the past several decades. Highlighting this importance, Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2017 stated that “whoever becomes the leader in this sphere will become the ruler of the world.” AI-guided IO tools can empathize with an audience to say anything, in any way needed, to change the perceptions that drive those physical weapons. Future IO systems will be able to individually monitor and affect  Next-generation bot armies will employ far faster computing techniques and profit from an order of magnitude greater network speed when 5G services are fielded. If “Repetition is a key tenet of IO execution,” then this machine gun-like ability to fire information at an audience will, with empathetic precision and custom content, provide the means to change a decisive audience’s very reality. No breakthrough science is needed, no bureaucratic project office required. These pieces are already there, waiting for an adversary to put them together.

Next-generation bot armies will employ far faster computing techniques and profit from an order of magnitude greater network speed when 5G services are fielded. If “Repetition is a key tenet of IO execution,” then this machine gun-like ability to fire information at an audience will, with empathetic precision and custom content, provide the means to change a decisive audience’s very reality. No breakthrough science is needed, no bureaucratic project office required. These pieces are already there, waiting for an adversary to put them together. One future vignette posits Russia’s GRU (Military Intelligence) employing AI Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to create fake persona injects that mimic select U.S. Active Army, ARNG, and USAR commanders making disparaging statements about their confidence in our allies’ forces, the legitimacy of the mission, and their faith in our political leadership. Sowing these injects across unit social media accounts, Russian Information Warfare specialists could seed doubt and erode trust in the chain of command amongst a percentage of susceptible Soldiers, creating further friction.

One future vignette posits Russia’s GRU (Military Intelligence) employing AI Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to create fake persona injects that mimic select U.S. Active Army, ARNG, and USAR commanders making disparaging statements about their confidence in our allies’ forces, the legitimacy of the mission, and their faith in our political leadership. Sowing these injects across unit social media accounts, Russian Information Warfare specialists could seed doubt and erode trust in the chain of command amongst a percentage of susceptible Soldiers, creating further friction. ‘Internet’ infrastructure for BRICS nations [Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa], which would continue to work in the event the global Internet malfunctions.” Security Council members argued the Internet’s threat to national security is due to:

‘Internet’ infrastructure for BRICS nations [Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa], which would continue to work in the event the global Internet malfunctions.” Security Council members argued the Internet’s threat to national security is due to: Syria experience — and monitoring the U.S. use of unmanned systems for the past two decades — convinced the Ministry of Defense (MOD) that its forces need more expanded unmanned combat capabilities to augment existing Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) systems that allow Russian forces to observe the battlefield in real time.

Syria experience — and monitoring the U.S. use of unmanned systems for the past two decades — convinced the Ministry of Defense (MOD) that its forces need more expanded unmanned combat capabilities to augment existing Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) systems that allow Russian forces to observe the battlefield in real time. However, in a candid admission, Andrei P. Anisimov, Senior Research Officer at the 3rd Central Research Institute of the Ministry of Defense, reported on the Uran-9’s critical combat deficiencies during the 10th All-Russian Scientific Conference entitled “Actual Problems of Defense and Security,” held in April 2018. The Uran-9 is a test bed system and much has to take place before it could be successfully integrated into current Russian concept of operations. What is key is that it has been tested in a combat environment and the Russian military and defense establishment are incorporating lessons learned into next-gen systems. We could expect more eye-opening lessons learned from its’ and other UGVs potential deployment in combat.

However, in a candid admission, Andrei P. Anisimov, Senior Research Officer at the 3rd Central Research Institute of the Ministry of Defense, reported on the Uran-9’s critical combat deficiencies during the 10th All-Russian Scientific Conference entitled “Actual Problems of Defense and Security,” held in April 2018. The Uran-9 is a test bed system and much has to take place before it could be successfully integrated into current Russian concept of operations. What is key is that it has been tested in a combat environment and the Russian military and defense establishment are incorporating lessons learned into next-gen systems. We could expect more eye-opening lessons learned from its’ and other UGVs potential deployment in combat. Intelligence (AI) program. The Russian MOD has already communicated its desire to have unmanned military systems operate autonomously in a fast-paced and fast-changing combat environment. While the actual technical solution for this autonomy may evade Russian designers in this decade due to its complexity, the MOD will nonetheless push its developers for near-term results that may perhaps grant such fighting vehicles limited semi-autonomous status. The MOD would also like this AI capability be able to direct swarms of air, land, and sea-based unmanned and autonomous systems.

Intelligence (AI) program. The Russian MOD has already communicated its desire to have unmanned military systems operate autonomously in a fast-paced and fast-changing combat environment. While the actual technical solution for this autonomy may evade Russian designers in this decade due to its complexity, the MOD will nonetheless push its developers for near-term results that may perhaps grant such fighting vehicles limited semi-autonomous status. The MOD would also like this AI capability be able to direct swarms of air, land, and sea-based unmanned and autonomous systems.

Russia’s embrace of these and other disruptive technologies and the way in which they adopt hybrid strategies that challenge traditional symmetric advantages and conventional ways of war increases their ability to challenge U.S. forces across multiple domains. As an authoritarian regime, Russia is able to more easily ensure unity of effort and a whole-of-government focus over the Western democracies. It will continue to seek out and exploit fractures and gaps in the U.S. and its allies’ decision-making, governance, and policy.

Russia’s embrace of these and other disruptive technologies and the way in which they adopt hybrid strategies that challenge traditional symmetric advantages and conventional ways of war increases their ability to challenge U.S. forces across multiple domains. As an authoritarian regime, Russia is able to more easily ensure unity of effort and a whole-of-government focus over the Western democracies. It will continue to seek out and exploit fractures and gaps in the U.S. and its allies’ decision-making, governance, and policy.

Intelligentized warfare will see the integration of military and non-military domains; and the boundary between peacetime and wartime will get

Intelligentized warfare will see the integration of military and non-military domains; and the boundary between peacetime and wartime will get Such asymmetric cryptography, which today is quite prevalent and integral to the security of our information technology ecosystem, relies upon the difficulty of prime factorization, a task beyond the capabilities of today’s classical computers but that could be cracked by a future quantum computer. The impact could be analogous to the advantage that the U.S. achieved through the efforts of American code-breakers ahead of the Battle of Midway.

Such asymmetric cryptography, which today is quite prevalent and integral to the security of our information technology ecosystem, relies upon the difficulty of prime factorization, a task beyond the capabilities of today’s classical computers but that could be cracked by a future quantum computer. The impact could be analogous to the advantage that the U.S. achieved through the efforts of American code-breakers ahead of the Battle of Midway. China plans to lead the world in precision medicine and human enhancement. In November 2018, Chinese Scientist Dr. He Jiankui claimed to have used CRISPR/Cas9 to edit the CCR5 gene of human embryos to generate an inherited resistance to HIV, smallpox, and cholera. Although it appears that this genetic modification will create a resistance to certain types of infections, altering CCR5 expression may have other phenotypic effects, as well. For example, studies have shown that the deletion of the CCR5 gene may affect memory; and therefore this specific gene edit may have modified the cognitive functions of these “CRISPR babies.”

China plans to lead the world in precision medicine and human enhancement. In November 2018, Chinese Scientist Dr. He Jiankui claimed to have used CRISPR/Cas9 to edit the CCR5 gene of human embryos to generate an inherited resistance to HIV, smallpox, and cholera. Although it appears that this genetic modification will create a resistance to certain types of infections, altering CCR5 expression may have other phenotypic effects, as well. For example, studies have shown that the deletion of the CCR5 gene may affect memory; and therefore this specific gene edit may have modified the cognitive functions of these “CRISPR babies.” efficient – to pursue the use of gene-edited agents in “mass disruptive” non-kinetic engagements. Such precision disruption can exploit a society’s vulnerabilities, and generate ripple effects to unsettle various domains and dimensions of geo-political stability and power. For example, allowing human use of gene editing techniques could foster attraction of both researchers seeking to advance potential translational applications of genetic methods (i.e., “research tourism”), and patients seeking newly developed gene-editing interventions (i.e., “medical tourism”) for the treatment of certain diseases as well as genetic modification for “wellness” and/or enhancement. Moreover, the use of gene editing techniques to modify crops, livestock, and to change environmental flora and fauna can incur equally disruptive effects on global ecologies, markets, and economics.

efficient – to pursue the use of gene-edited agents in “mass disruptive” non-kinetic engagements. Such precision disruption can exploit a society’s vulnerabilities, and generate ripple effects to unsettle various domains and dimensions of geo-political stability and power. For example, allowing human use of gene editing techniques could foster attraction of both researchers seeking to advance potential translational applications of genetic methods (i.e., “research tourism”), and patients seeking newly developed gene-editing interventions (i.e., “medical tourism”) for the treatment of certain diseases as well as genetic modification for “wellness” and/or enhancement. Moreover, the use of gene editing techniques to modify crops, livestock, and to change environmental flora and fauna can incur equally disruptive effects on global ecologies, markets, and economics. is far more feasible, facile – and therefore of greater value – to consider and pursue the brain sciences for producing “mass disruption” effects in non-kinetic engagements. Weaponry (i.e., means of contending against others) can be generally categorized as “Hard” and “Soft.” “Hard” weaponized applications of neuroS/T include pharmacological agents, microbes, organic toxins, and devices (i.e., “drugs, bugs, toxins, and tech”). Research, development, and use of these weapons are regulated by current international conventions and treaties, at least to some extent; and the scope and limitations of these treaties remain a focus of international discussion, contention, and debate. But it is equally important to acknowledge the capability that can be leveraged by employing forms of neuroS/T as “soft” weapons, to influence multinational, if not global economic, social, and political stability as well as balances of power.

is far more feasible, facile – and therefore of greater value – to consider and pursue the brain sciences for producing “mass disruption” effects in non-kinetic engagements. Weaponry (i.e., means of contending against others) can be generally categorized as “Hard” and “Soft.” “Hard” weaponized applications of neuroS/T include pharmacological agents, microbes, organic toxins, and devices (i.e., “drugs, bugs, toxins, and tech”). Research, development, and use of these weapons are regulated by current international conventions and treaties, at least to some extent; and the scope and limitations of these treaties remain a focus of international discussion, contention, and debate. But it is equally important to acknowledge the capability that can be leveraged by employing forms of neuroS/T as “soft” weapons, to influence multinational, if not global economic, social, and political stability as well as balances of power. polar satellite — the BNU-1 has successfully obtained data on the polar regions and is conducting full-coverage observation of the Antarctic and the Arctic every day. Developed by the Beijing Normal University and Shenzhen Aerospace Dongfanghong Development Ltd., the satellite will promote research of the Earth’s polar regions and support China’s upcoming 36th Antarctic expedition by enhancing its navigation capability in the polar ice zone.

polar satellite — the BNU-1 has successfully obtained data on the polar regions and is conducting full-coverage observation of the Antarctic and the Arctic every day. Developed by the Beijing Normal University and Shenzhen Aerospace Dongfanghong Development Ltd., the satellite will promote research of the Earth’s polar regions and support China’s upcoming 36th Antarctic expedition by enhancing its navigation capability in the polar ice zone. China’s first ice breaker, Xue Long [Snow Dragon] doubles as a polar research vessel and has spent most of her time in the Arctic and Antarctic including over 20 annual Chinese Antarctic expeditions. The vessel was built in Soviet Ukraine shipyards in 1993. Xinhuanet reports that Xue Long 2, built in China, will probably make the Antarctic voyage this year. China maintains the Taishan Station in Antarctica. The development of the Nanji 2 all-terrain amphibious polar vehicle will support the station and other polar research.

China’s first ice breaker, Xue Long [Snow Dragon] doubles as a polar research vessel and has spent most of her time in the Arctic and Antarctic including over 20 annual Chinese Antarctic expeditions. The vessel was built in Soviet Ukraine shipyards in 1993. Xinhuanet reports that Xue Long 2, built in China, will probably make the Antarctic voyage this year. China maintains the Taishan Station in Antarctica. The development of the Nanji 2 all-terrain amphibious polar vehicle will support the station and other polar research. our short, on-line

our short, on-line