[Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist Laboratory is pleased to publish the following post by guest blogger Dr. Jan Kallberg, faculty member, United States Military Academy at West Point, and Research Scientist with the Army Cyber Institute at West Point. … Read the rest

69. Demons in the Tall Grass

[Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist is pleased to present Mr. Mike Matson‘s guest blog post set in 2037 — pitting the defending Angolan 6th Mechanized Brigade with Russian advisors and mercenaries against a Namibian Special Forces incursion supported by … Read the rest

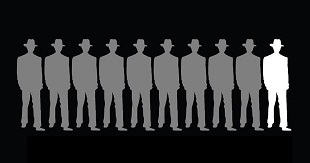

67. “The Tenth Man”

[Editor’s Note: In the movie World War Z (I know… the book was way better!), an Israeli security operative describes how Israel prepared for the coming zombie plague. Their strategy was if nine men agreed on an analysis or … Read the rest

64. Top Ten Takeaways from the Installations of the Future Conference

On 19-20 June 2018, the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) Mad Scientist Initiative co-hosted the Installations of the Future Conference with the Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Installations, Energy and Environment (OASA (IE&E)) and … Read the rest

On 19-20 June 2018, the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) Mad Scientist Initiative co-hosted the Installations of the Future Conference with the Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Installations, Energy and Environment (OASA (IE&E)) and … Read the rest

60. Mission Engineering and Prototype Warfare: Operationalizing Technology Faster to Stay Ahead of the Threat

[Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist is pleased to present the following post by a team of guest bloggers from The Strategic Cohort at the U.S. Army Tank Automotive Research, Development, and Engineering Center (TARDEC). Their post lays out a … Read the rest