[Editor’s Note: Last month, our colleagues at Military Review published Three Dates, Three Windows, and All of DOTMLPF-P, by Ian Sullivan, Deputy Chief of Staff, Intelligence (DCSINT), U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) G-2, describing the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) ongoing efforts to transform the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) into a force capable of “challeng[ing] the U.S. Army and joint force across the three areas that have underpinned U.S. military dominance in the post-Desert Storm period: dominance in materiel, dominance in soldiers and leaders, and dominance in approach to warfare.”

A year ago, CIA Director William Burns stated “that the United States knew ‘as a matter of intelligence’ that Xi had ordered his military to be ready to conduct an invasion of self-governed Taiwan by 2027.” Director Burns elaborated, “Now, that does not mean that he’s decided to conduct an invasion in 2027, or any other year, but it’s a reminder of the seriousness of his focus and his ambition,”

Today’s post excerpts sections of Mr. Sullivan’s seminal piece — examining how the years 2027, 2035, and 2049 provide context for the PLA’s on-going force modernization drive and exploring the associated windows of vulnerability presented for the U.S. Army and the Joint Force — Enjoy!]

Three Dates

The PLA modernization challenge does not exist in a vacuum. It is part of a broader plan by the CCP to create “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” by the year 2049, which is the centennial of the foundation of the People’s Republic of China. It is part of a broad Party-led effort to secure for China “a leading place” in the world. To get there, the Party will work to generate and employ all elements of national power to defend its sovereignty, maintain internal stability, and protect its growing interests regionally and globally to allow for its economic development.[i] China has been engaged in a broad “whole-of-nation” effort to achieve these goals, including such efforts as the Belt and Road Initiative, its “three warfares” construct for Great Power competition, leadership in international organizations, and a renewed focus on diplomacy (its role in the BRICs, its work to restore relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran, and even its political engagement to resolve the Russia-Ukraine War). But it is a modernized PLA capable of asserting itself both regionally and globally that is a necessary backbone to this entire revitalization of a CCP-led Chinese state.

CCP leadership has not been shy in talking about PLA military modernization, particularly in terms of laying out its ambitious timelines. Initially there were two dates that mattered—2035 and 2049—but a third, 2027, has recently come to the forefront in terms of where China is going. These dates need to be addressed in reverse order, starting with 2049.

The year 2049 is a big one for Beijing and the CCP, as discussed above. But it has more concrete meaning for the PLA, too. The 19th Party Congress, which was held in October 2017, presented both the rationale and the objective of the PLA’s military modernization program. It is intended to create a force that is inextricably linked to the CCP that can manage crises, deter its adversaries, and win wars. It also notes that the overall intent of the program is to transform the PLA by 2049 into a “world-class” military.[ii] While not specifically defined, this very likely means developing a military that is at least equivalent to the United States and some of its Western partners. In terms of capabilities, the PLA of 2049 should be expected to be able to deploy forces across all domains globally to protect Chinese interests.[iii]

Keeping in mind Mike Tyson’s dictum on strategy, it was Xi himself who provided this plan with the proverbial punch in the mouth by offering a third date of relevance; 2027. The relevance of 2027—the centennial of the founding of the PLA—came to the forefront of the seminal 20th Party Congress, which occurred in October 2022. The 20th Party Congress represented not only the codification of Xi’s authority, arguably making him the most powerful and relevant Chinese leader since Mao, but also a demonstration of a shift in thinking in terms of China’s security situation. Indeed, it specifically referenced “drastic changes in the international landscape,” which was a departure from the 19th Party Congress focus on economic development and stability. The military ramifications of the 20th Party Congress demonstrate a sense of urgency on the part of the CCP that is rarely seen. It called for speeding up the modernization effort across the board. It instructed the PLA to regularly deploy its forces; to establish a strong deterrent; to increase “new domain forces” (cyber and space); increase the use of unmanned systems, and to rapidly complete its modernization effort.[vi] Indeed, the 2027 date could be seen as a new modernization benchmark, potentially replacing 2035 as a target.

Three Windows

The three dates create three windows of vulnerability for the Army and the Joint Force. The first is a “Fight Tonight” reality, where regional tensions could boil over, an accidental close approach of a PLA asset and U.S. or Allied forces could lead to an exchange of fire, or some third-party action could lead to a rapid conflict between China and the United States. This period runs from the present out two years to 2025. The second is a “Fight in the Near-Term” window, starting in 2025 and ending in 2030. It is a period focused on Xi’s new 2027 proclamation of being ready to fight in Taiwan. It also is a particularly dangerous period for the U.S. Army, as a fight occurring before 2030 will be inside the Army’s key modernization benchmark of delivering the Army of  2030. In such a scenario, China’s modernization program and drive to intelligentization would be ahead of the Army’s and the Joint Force’s drive to Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2). Finally, the threat window after 2030—the “Fight in the Future”—would see a modernized U.S. Army capable of waging Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) with its own 2030 modernization benchmark complete. It would also be a time where the PLA and the U.S. Army (and Joint Force) are locked in a continuous struggle to garner material advantage through China’s 2049 benchmark.

2030. In such a scenario, China’s modernization program and drive to intelligentization would be ahead of the Army’s and the Joint Force’s drive to Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2). Finally, the threat window after 2030—the “Fight in the Future”—would see a modernized U.S. Army capable of waging Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) with its own 2030 modernization benchmark complete. It would also be a time where the PLA and the U.S. Army (and Joint Force) are locked in a continuous struggle to garner material advantage through China’s 2049 benchmark.

“Fight Tonight”

The “Fight Tonight” window is dominated by current events. Tensions between China and the United States have been increasing for some time, but they have intensified since Congresswoman Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August 2022. Likely viewing it through the lens of continual U.S. interference in China’s rise, Beijing expressed extreme displeasure with the visit. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi called the United States the “biggest destroyer of peace across the Taiwan Strait and for regional stability,” and added “China will definitely take all necessary measures to resolutely safeguard its sovereignty and territorial integrity in response to the (then) U.S. Speaker’s visit.”[vii] In the days following the visit, the PLA’s Eastern Theater Command stepped up ongoing exercises to include the deployment of more than 200 aircraft and 50 warships in and around Taiwan.[viii] They also fired eleven ballistic missiles off Taiwan’s north-east and south-west coasts.[ix] In the year that followed Congresswoman Pelosi’s visit, PLAAF aircraft conducted hundreds of violations of Taiwanese airspace, including more than 140 across the Taiwan Strait center-line, involving some 1,000 aircraft. Between 2020 and the visit in 2022, although the PLAAF violated Taiwanese airspace frequently, there were only two instances of center-line violations.[x] Between April and September, the PLA has conducted a series of exercises involving elements of all its services off Taiwan.

China has not limited its activities to exercises off Taiwan. There have been several highly dangerous “close encounters” between PLAN and U.S. warships, as well as unprofessional intercepts of U.S. aircraft in international waters and airspace. The most dramatic encounter was between a PLAN LUYANG-III DDG and the USS Chung-Hoon, an Arleigh Burke-class DDG in which the Chinese destroyer closed to within 150 yards and forced Chung-Hoon to veer away.[xi] Just days before, a PLAAF J-16 fighter flew directly in front of the nose of a U.S. Air Force RC-135 Rivet Joint reconnaissance aircraft flying in international airspace over the South China Sea, forcing the U.S. aircraft to fly through dangerous turbulence.[xii]

Finally, China’s ambitions in the South China Sea have led to a very dangerous situation in which the Chinese Coast Guard and Maritime Militia have worked to thwart efforts by the Philippines to resupply its outpost—a rusted, grounded ship—in the Second Thomas Shoal in the disputed Spratly Islands. Although well within Manilla’s exclusive economic zone, China claims the Second Thomas Shoal, and its Coast Guard and Maritime Milita have worked to deny three efforts by the Philippines Coast Guard to resupply the beleaguered station. Chinese actions have included dangerous close encounters, and even the use of water cannon against Philippines re-supply ships.[xiii]

Taken together these actions demonstrate increased PLA activity in the region aimed at Taiwan, the United States, and its Allies and Partners which could potentially spiral and create an armed escalation leading to a conflict. These types of activities are examples of broader Chinese efforts across the region which could lead to a crisis, and even conflict, if not managed carefully. It demonstrates how quickly the “Fight Tonight” threat window could ignite.

“Fight in the Near-Term”

The “Fight in the Near-Term” window is a bit more complex but revolves around’s Xi’s shift to 2027 as the date for the PLA to complete parts of modernization and to be ready for Taiwan. Despite his wishes, it is unlikely that the PLA will fully and completely implement its modernization efforts within the next four years. It will, however, complete significant pieces of it, and when taken together with what it already has achieved, could create a near-term advantage for the PLA in terms of modernization over the Army, whose own modernization efforts do not completely crystalize until 2030. The newly salient 2027 waypoint between the already completed 2020 goal of “informationized warfare” and “mechanization” and the 2035 “intelligentization” becomes critical, particularly when taken with Xi’s guidance to the PLA to be ready to take Taiwan by the same year.

The focus of 2027 would not necessarily be on new capabilities—although new systems will continue to roll out and be deployed across the PLA between now and 2030—but instead will be on force structure reforms and professionalization, which are critical if the PLA is to become a force capable of waging intelligentized warfare[xiv] It will, however, take advantage of new systems that already have come online, and what has come online thus far has been impressive.

The PLA Army by 2022 has revamped its formations, and now 70 percent of its main battle tanks can be considered “modern,” while 60 percent of its Heavy and Medium Combined Arms Brigades are now equipped with modern tracked or wheeled infantry fighting vehicles.[xv]

The PLAN is now the world’s largest Navy, and its rapid deployment of new warships means its fleet is largely modern and capable. As of 2023, it fields 340 ships in its battle force (and another 85 missile-armed patrol combatants). By 2025 this number will surge to 400 and will then increase again to 440 by 2030.[xvi]

The PLAAF has standardized its fighter force around three aircraft – the J-10, the J-16, and the Fifth Generation J-20. It now fields over 600 aircraft in 19 brigades and has doubled the production of the J-10 and J-16 over the last three years. More than 150 J-20s are now in service. They have fielded new capable air-to-air missiles like the PL-15 and PL-16, and increased the fielding of Y-20 transport aircraft, which are similar in function to the U.S. C-17.[xvii]

The PLA Rocket Force (PLARF) has seen a variety of new systems come on line, including the DF-21 (which includes an anti-ship variant designed to target U.S. aircraft carriers), the DF-26 (known as the “Guam Killer”), the DF-17 hypersonic missile, and two new ICBMs—the DF-31 and DF-41. The PLARF also is expanding its nuclear arsenal, which is expected to have 700 warheads by 2027 and 1,000 by 2030. This even includes a fractional orbital bombardment system (FOBS) capability that was revealed in 2021.[xviii]

As noted, however, the 2027 threat window is about more than materiel. It is about people, readiness, and organizational change, and the PLA is working to implement and codify both. In terms of people, China is working to modernize its approach. Beijing’s 2019 Defense White Paper stated that “military training in real combat conditions across the armed forces is in full swing.”[xix] The PLA has come to the realization that modern warfare will unfold across domains, and by necessity, will be inherently joint.

To successfully undertake this approach to war, which is covered under their drive toward intelligentization, the PLA recognized that they required more capable personnel and leaders. The PLA has been working to improve its training and professional military education (PME) since the mid-1980s, but never with the focus and intensity that we have seen with this current 2017 modernization effort. Starting as early as 2015, the PLA began speaking of the “Triad New Military Talent Education System of Systems,” which they worked to implement between 2017 and 2020. The Triad comprised three separate legs: military academies, unit training, and PME,[xx] and brings along with it a host of improvements to what had been a stilted system that was largely incapable of producing effective human capital. This effort has included transforming its academy system to promote critical thinking and innovation, as well as offer advanced degrees and joint warfare certification, making training more realistic at the unit level, and to create deeper PME opportunities using state-of-the art Western educational concepts.[xxi]

These efforts are designed to lay a foundation for an improved PLA, but they will take time to bear fruit. The PLA already is facing key structural problems as it works to make these changes, ranging from curricula design, controlling corruption, and modernizing pay and benefits to attract and retain faculty.[xxii] But they have made a start. For example, using the model of the Five Incapables, the PLA knows what it is looking for in terms of developing the leadership traits it wishes to reinforce through its PME and training for its officers. These include political loyalty to the CCP, strategic awareness, being skilled at military affairs (able to lead and command military operations), adherence to military culture (what the U.S. Army might call being committed to the profession of arms), being adaptive, and having intangible leadership traits (charisma, flexibility, institutional leadership, etc.).[xxiii] But developing these leaders will be no easy task, as they will need to overcome some very critical and difficult challenges, some of which have no easy fix. First, they must reconcile developing the type of innovative leader they believe they need, but within the all-encompassing leadership mechanism of the CCP, of which the PLA is a part. Second, they must overcome the endemic corruption that has dominated PLA affairs for generations. Third, they must implement what they think they need without having a reservoir of broad experiences upon which to draw. PLA officers have a relatively narrow base of experience; there are few broadening assignments available to them.[xxiv] They also, of course, lack a reservoir of combat experience. While Xi has focused heavily on rooting out corruption within the PLA, the other two are more difficult to address.

A more difficult problem involves the development of a capable and competent cadre of non-commissioned officers (NCOs). Traditionally the backbone of Western militaries, the PLA has struggled to develop NCOs. Their current modernization, however, recognizes the need to focus on NCO development, but thus far, it appears to have taken a back seat to officer development. Nevertheless, the PLA has made some progress. In March 2022, the PLA issued its “Interim Regulations for Sergeants,” which revealed some of the steps the PLA is taking to improve its NCO corps. The first is that the PLA has two different types of NCOs: management and skilled. The first deal with traditional NCO leadership tasks, while the second are technical experts. Furthermore, these regulations delved deeper into how the PLA is working to recruit its NCO corps to develop these NCOs. There are three paths PLA soldiers can take into the NCO corps. The first is the traditional model, where NCOs are selected from the pool of conscripts who completed their two years of service and then volunteered to extend their time in the military. These personnel generally gravitate to the management NCO. The second involves the recruitment of an “NCO-cadet” who is recruited directly from high school due to technical aptitude. They receive three years of training; two-and-half years of technical training and then half a year of military field training before serving another three years as an NCO, generally in a technical area. The third is a direct recruit NCO who is a civilian with a bachelor’s degree who joins immediately as a corporal. For the latter two types of NCOs, the PLA is looking largely for individuals with engineering, information technology, and data science experience.[xxv]

But there are still key obstacles that that PLA must overcome here, with the most significant being a lack of experience and the general lack of quality training and education systems for the NCO corps. While this certainly creates an institutional weakness, the PLA’s general approach to systems of systems warfare may be less reliant on high-quality NCOs, namely because it is focused heavily on the use of long-range fires to target the systems that allow their adversaries’ military mechanism to function.[xxvi] However, the steps that the PLA has taken thus far has put them on the path to creating a more effective NCO, particularly in terms of technical expertise.[xxvii]

When taken as a whole, the “Fight in the Near-Term” window creates a significant challenge for the U.S. Joint Force. It may represent the most dangerous of the three windows where our potential adversary’s modernization effort is inside of our own, they will have made progress on their journey toward intelligentized warfare, and they will start to see an improved form of human capital in the ranks of the PLA, although certainly not yet on par with the United States or its key Allies. It is in this window where the human dimension will be the U.S. Army and Joint Force’s critical advantage, and it’s absolutely imperative that we maintain this edge and prepare this force through focused training and PME.

“Fight in the Future”

The third threat window is “Fight in the Future.” This admittedly is the most difficult to understand, as it focuses on that critical area between 2030 and 2050. If China’s plans hold, it is when the PLA becomes the world’s leading military and China itself enjoys its broad national rejuvenation. In this phase, the PLA will more fully integrate and develop advanced technologies to multiply its combat capabilities and to effectively collapse an adversary’s ability to wage warfare by targeting the reinforcing systems – command and  control; fires; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR); and logistics. The technologies that China will develop and the PLA will employ in this window will create a synergistic effect that the PLA describes as “1+1>2.”[xxviii] We have already discussed intelligentized warfare, but in this Threat Window, we see the threat transforming into a broad strategic struggle between the United States and its Allies and China to harness advanced technologies, particularly those related to AI, which China increasingly sees as the true focus of future Great Power competition. The 2019 Defense White Paper stated “International military competition is undergoing historic changes. New and high-tech military technologies based on IT are developing rapidly. There is a prevailing trend to develop long-range precision, intelligence, stealthy, or unmanned weaponry and equipment.”[xxix] When combined with the systems of systems warfare concept that underpins Chinese military thinking, it is easy to understand the gravity of this threat.

control; fires; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR); and logistics. The technologies that China will develop and the PLA will employ in this window will create a synergistic effect that the PLA describes as “1+1>2.”[xxviii] We have already discussed intelligentized warfare, but in this Threat Window, we see the threat transforming into a broad strategic struggle between the United States and its Allies and China to harness advanced technologies, particularly those related to AI, which China increasingly sees as the true focus of future Great Power competition. The 2019 Defense White Paper stated “International military competition is undergoing historic changes. New and high-tech military technologies based on IT are developing rapidly. There is a prevailing trend to develop long-range precision, intelligence, stealthy, or unmanned weaponry and equipment.”[xxix] When combined with the systems of systems warfare concept that underpins Chinese military thinking, it is easy to understand the gravity of this threat.

If you enjoyed this post, read Ian Sullivan‘s complete article here, published by our colleagues at Military Review…

… then check out the following related TRADOC G-2 and Mad Scientist content:

The TRADOC G-2‘s Operational Environment Enterprise public facing page, with a plethora of content about our pacing challenge at the China Landing Zone, including ATP 7-100.3, Chinese Tactics, BiteSize China weekly topics, People’s Liberation Army Ground Forces Quick Reference Guide, and our thirty-plus snapshots captured to date addressing what China is learning about the Operational Environment from Russia’s war against Ukraine (note that a DoD Common Access Card [CAC] is required to access this last link).

The Most Consequential Adversaries and associated podcast, with GEN Charles A. Flynn

Volatility in the Pacific: China, Resilience, and the Human Dimension and associated podcast, with General Robert Brown (USA-Ret.)

How China Fights and associated podcast

China and Russia: Achieving Decision Dominance and Information Advantage, and “No Option is Excluded” — Using Wargaming to Envision a Chinese Assault on Taiwan by Ian Sullivan

Flash-Mob Warfare: Whispers in the Digital Sandstorm (Parts 1 and 2), by Dr. Robert E. Smith

China: Building Regional Hegemony and China 2049: The Flight of a Particle Board Dragon, the comprehensive report from which this post was excerpted

The U.S. Joint Force’s Defeat before Conflict, by CPT Anjanay Kumar

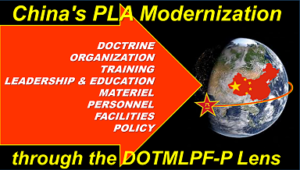

China’s PLA Modernization through the DOTMLPF-P Lens, by Dr. Jacob Barton

Intelligentization and the PLA’s Strategic Support Force, by Col (s) Dorian Hatcher

“Intelligentization” and a Chinese Vision of Future War

Competition and Conflict in the Next Decade

Disrupting the “Chinese Dream” – Eight Insights on how to win the Competition with China

Competition in 2035: Anticipating Chinese Exploitation of Operational Environments

Disinformation, Revisionism, and China with Doowan Lee and associated podcast

China and Russia: Achieving Decision Dominance and Information Advantage, by Ian Sullivan

The PLA and UAVs – Automating the Battlefield and Enhancing Training

A Chinese Perspective on Future Urban Unmanned Operations

China: “New Concepts” in Unmanned Combat and Cyber and Electronic Warfare

The PLA: Close Combat in the Information Age and the “Blade of Victory”

About the Author: Ian Sullivan is the Deputy Chief of Staff, G-2 for the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC). He holds a BA from Canisius University in Buffalo, New York, and an MA from Georgetown University’s BMW Center for German and European Studies in Washington, D.C., and he was a Fulbright Fellow at the Universität Potsdam in Potsdam, Germany. A career civilian intelligence officer, Mr. Sullivan has served with the Office of Naval Intelligence; Headquarters, U.S. Army Europe and Seventh Army; the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) at the National Counterterrorism Center; the Central Intelligence Agency; and TRADOC. He is a member of the Defense Intelligence Senior Executive Service and was first promoted to the senior civilian ranks in 2013 as a member of the ODNI’s Senior National Intelligence Service.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

[i] U.S. Department of Defense, “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China: Annual Report to Congress, 2022, 1-2.

[ii] Ibid., 32-33.

[iii] Sameer Patil, “China’s Military Modernization,” Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations, 31 March 2022.

[iv] Koichiro Takagi, “New Tech, New Concepts: China’s Plans for AI and Cognitive Warfare,” War on the Rocks, 13 April 2022.

[v] Meia Nouwens, “China’s Military Modernization: Will the People’s Liberation Army Complete its Reforms?”, IISS Strategic Survey 2022, 7 December 2022.

[vi] U.S. Department of Defense, 5.

[vii] Wang Yi, quoted in David Sacks, “As China Punishes Taiwan for Pelosi Visit, What Comes Next,” Council on Foreign Relations Blog, 4 August 2022.

[viii] Ishaan Tharor, ”China Shifts the Military Status Quo After Pelosi Visit,” The Washington Post, 9 August 2022.

[ix] Alys Davies and Yaroslav Lukov, “China Fires Missiles Near Taiwan After Pelosi Visit,” British Broadcasting Corporation, 4 August 2022.

[x] Adrian Ang U-Jin and Olli Pekka Suorsa, “Since the Pelosi Visit, China Has Created a New Normal in the Taiwan Strait,” The Diplomat, 10 August 2023.

[xi] Michael Martina and Martin Quin Pollard, “Why Dangerous Encounters by U.S. and Chinese Militaries Look Set to Continue,” Reuters, 6 June 2023.

[xii] U.S. Indo-Pacific Command Public Affairs, “USINDPACOM Statement on Unprofessional Intercept of U.S. Aircraft over South China Sea,” 30 May 2023.

[xiii] Dzirhan Mahadzir, “Chinese Warships Shadow Canadian, U.S., Japanese Warships in East China Sea, the Philippines Resupply Second Thomas Shoal,” USNI News, 8 September 2023.

[xiv] Nouwens.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Congressional Research Service, “China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress,” 15 May 2023, 3-6.

[xvii] Douglass Barrie, Henry Boyd, and James Hackett, “China’s Air Force Modernisation: Gaining Pace”, IISS Military Balance Blog, 21 February 2023.

[xviii] Nouwens.

[xix] The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, “China’s National Defense in the New Era,” July 2019.

[xx] Kevin McCauley, “”Triad” Military Education and Training Reforms: The PLA’s Cultivation of Talent for Integrated Joint Operations,” The Jamestown Foundation China Brief, 5 March 2019.

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] Roderick Lee, “Building the Next Generation of Chinese Military Leaders,” Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, U.S. Air Force Air University, 31 August 2020.

[xxiv] Ibid.

[xxv] Matt Tetreau, “The PLA’s Weak Backbone: Is China Struggling to Professionalize its Noncommissioned Officer Corps?, Modern War Institute, West Point, 1 January 2023.

[xxvi] Sydney Freedberg Jr., “PRC, Russia Professionalize – Without Cloning US NCOs,” Breaking Defense, 21 June, 2021.

[xxvii] Tetreau.

[xxviii] Kevin McCauley, “People’s Liberation Army Transitioning From “Informationized” to Intelligent Warfare Concepts,” OE Watch, U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command Foreign Military Studies Office, Volume 13, Issue 7, 2023, 8.

[xxix] The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, “China’s National Defense in the New Era,” July 2019.