[Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist Laboratory is pleased to present today’s guest blog post by Mr. Brady Moore and Mr. Chris Sauceda, addressing how Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems and entities conducting machine speed collection, collation, and analysis of battlefield information will free up warfighters and commanders to do what they do best — fight and make decisions, respectively. This Augmented Intelligence will enable commanders to focus on the battle with coup d’œil, or the “stroke of an eye,” maintaining situational awareness on future fights at machine speed, without losing precious time crunching data.]

In the 1996 film Swingers, the characters Trent (played by Vince Vaughn) and Mike (played by Jon Favreau) star as a couple of young guys trying to make it in Hollywood. On a trip to Las Vegas, Trent introduces Mike as “the guy behind the guy” – implying that Mike’s value is that he has the know-how to get things done, acts quickly, and therefore is indispensable to a leading figure. Yes, I’m talking about Artificial Intelligence for Decision-Making on the future battlefield – and “the guy behind the guy” sums up how AI will provide a decisive advantage in Multi-Domain Operations (MDO).

Some of the problems commanders will have on future battlefields will be the same ones they have today and the same ones they had 200 years ago: the friction and fog of war. The rise of information availability and connectivity brings today’s challenges – of which most of us are aware. Advanced adversary technologies will bring future challenges for intelligence gathering, command, communication, mobility, and dispersion. Future commanders and their staffs must be able to deal with both perennial and novel challenges faster than their adversaries, in disadvantageous circumstances we can’t control. “The guy behind the guy” will need to be conversant in vast amounts of information and quick to act.

In western warfare, the original “guy behind the guy” wasn’t Mike – it was this stunning figure. Marshal Louis-Alexandre Berthier was Napoleon Bonaparte’s Chief of Staff from the start of his first Italian campaign in 1796 until his first abdication in 1814. Famous for rarely sleeping while on campaign, Paul Thiebault said of Berthier in 1796:

“Quite apart from his specialist training as a topographical engineer, he had knowledge and experience of staff work and furthermore a remarkable grasp of everything to do with war. He had also, above all else, the gift of writing a complete order and transmitting it with the utmost speed and clarity…No one could have better suited General Bonaparte, who wanted a man capable of relieving him of all detailed work, to understand him instantly and to foresee what he would need.”

Bonaparte’s military record, his genius for war, and skill as a leader are undisputed, but Berthier so enhanced his capabilities that even Napoleon himself admitted about his absence at Waterloo, “If Berthier had been there, I would not have met this misfortune.”

Augmented Intelligence, where intelligent systems enhance human capabilities (rather than systems that aspire to replicate the full scope of human intelligence), has the potential to act as a digital Chief of Staff to a battlefield commander. Just like Berthier, AI for decision-making would free up leaders to clearly consider more factors and make better decisions – allowing them to command more, and research and analyze less. AI should allow humans to do what they do best in combat – be imaginative, compel others, and act with an inherent intuition, while the AI tool finds, processes, and presents the needed information in time.

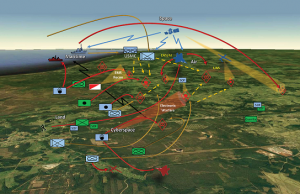

So Augmented Intelligence would filter information to prioritize only the most relevant and timely information to help manage today’s information overload, as well as quickly help communicate intent – but what about yesterday’s friction and fog, and tomorrow’s adversary technology? The future battlefield seems like one where U.S. commanders will be starved for the kind of Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) and communication we are so used to today, a battlefield with contested Electromagnetic Spectrum (EMS) and active cyber effects, whether known or unknown. How can commanders and their staffs begin to overcome challenges we haven’t yet been presented in war?

In his 2013 book Average is Over, economist Tyler Cowen examines the way freestyle chess players (who are free to use computers when playing the game) use AI tools to compete and win, and makes some interesting observations that are absolutely applicable to the future of warfare at every level. He finds competitors have to play against foes who have AI tools themselves, and that AI tools make chess move decisions that can be recognized (by people) and countered. The most successful freestyle chess players use a combination of their own knowledge of the game, but pick and choose times and situations to use different kinds of AI throughout a game. Their opponents not only then have to consider which AI is being used against them, but also their human operator’s overall strategy. This combination of Augmented Intelligence with an AI tool, along with natural inclinations and human intuitions will likely result in a powerful equilibrium of human and AI perception, analysis, and ultimately enhanced complex decision-making.

With a well-trained and versatile “guy behind the guy,” a commander and staff could employ different aspects of Augmented Intelligence at different times, based on need or appropriateness. A company commander in a dense urban fight, equipped with an appropriate AI tool – a “guy behind the guy” that helps him make sense of the battlefield – what could that commander accomplish with his company? He could employ the tool to notice things humans don’t – or at least notice them faster and alert him. Changes in historic traffic patterns or electronic signals in an area could indicate an upcoming attack or a fleeing enemy, or the system could let the commander know that just a little more specific data could help establish a pattern where enemy data was scarce. And if the commander was presented with the very complex and large problems that characterize modern dense urban combat, the system could help shrink and sequence problems to make them more solvable – for instance find a good subset of information to experiment with and help prove a hypothesis before trying out a solution in the real world – risking bandwidth instead of blood.

The U.S. strategy for MDO has already identified the critical need to observe, orient, decide, and act faster than our adversaries – multiple AI tools that have all necessary information, and can present it and act quickly will certainly be indispensable to leaders on the battlefield. An AI “guy behind the guy” continuously sizing up the situation, finding the right information and allowing for better, faster decisions in difficult situations is how Augmented Intelligence will best serve leaders in combat and provide battlefield advantage.

The U.S. strategy for MDO has already identified the critical need to observe, orient, decide, and act faster than our adversaries – multiple AI tools that have all necessary information, and can present it and act quickly will certainly be indispensable to leaders on the battlefield. An AI “guy behind the guy” continuously sizing up the situation, finding the right information and allowing for better, faster decisions in difficult situations is how Augmented Intelligence will best serve leaders in combat and provide battlefield advantage.

If you enjoyed this post, please also read:

- MAJ Vincent Duenas‘ post AI Enhancing EI in War

- Dr. Nir Buras‘ post Man-Machine Rules

- CW3 Jesse R. Crifasi‘s post The Human Targeting Solution: An AI Story

… watch Juliane Gallina‘s Arsenal of the Mind presentation at the Mad Scientist Robotics, AI, & Autonomy Visioning Multi Domain Battle in 2030-2050 Conference at Georgia Tech Research Institute, Atlanta, Georgia, on 7-8 March 2017

… and learn more about potential AI battlefield applications in our Crowdsourcing the Future of the AI Battlefield information paper.

Brady Moore is a Senior Enterprise Client Executive at Neudesic in New York City. A graduate of The Citadel, he is a former U.S. Army Infantry and Special Forces officer with service as a leader, planner, and advisor across Iraq, Afghanistan, Africa, and, South Asia. After leaving the Army in 2011, he obtained an MBA at Penn State and worked as an IBM Cognitive Solutions Leader covering analytics, AI, and Machine Learning in National Security. He’s the Junior Vice Commander of VFW Post 2906 in Pompton Lakes, NJ, and Cofounder of the Special Forces Association Chapter 58 in New York City. He also works with Elite Meet as often as he can.

Chris Sauceda is an account manager within the U.S. Army Defense and Intel IBM account, covering Command and Control, Cyber, and Advanced Analytics/ Artificial Intelligence. Chris served on active duty and deployed in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom, and has been in the Defense contracting business for over 13 years. Focused on driving cutting edge technologies to the warfighter, he also currently serves as a Signal Officer in the Texas Military Department.

Drone technology continues to proliferate in militaries and industries around the world. In the deep future, drones and drone swarms may extend physical conflict into the space domain. As space becomes ever more critical to military operations, states will seek technologies to counter their adversaries’ capabilities. Drones and swarms can blend in with space debris in order to provide a tactical advantage against vulnerable and expensive assets at a lower cost.

Drone technology continues to proliferate in militaries and industries around the world. In the deep future, drones and drone swarms may extend physical conflict into the space domain. As space becomes ever more critical to military operations, states will seek technologies to counter their adversaries’ capabilities. Drones and swarms can blend in with space debris in order to provide a tactical advantage against vulnerable and expensive assets at a lower cost.

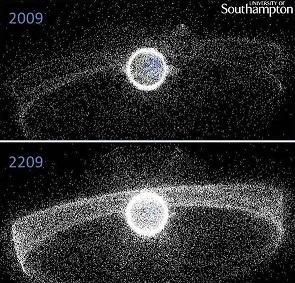

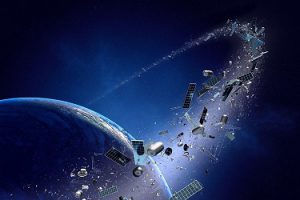

For outer space drones and drone swarms, the issue of space junk is a double-edged sword. While it camouflages the vehicles, drone and swarm attacks also produce more space junk due to their kinetic nature. One directed “kamikaze” or armed drone can severely damage or destroy a satellite, while swarm technology can be harnessed for use against larger, defended assets or in a coordinated attack. However, projecting shrapnel can hit other military or commercial assets, creating a

For outer space drones and drone swarms, the issue of space junk is a double-edged sword. While it camouflages the vehicles, drone and swarm attacks also produce more space junk due to their kinetic nature. One directed “kamikaze” or armed drone can severely damage or destroy a satellite, while swarm technology can be harnessed for use against larger, defended assets or in a coordinated attack. However, projecting shrapnel can hit other military or commercial assets, creating a

There are no facts about the future. Leaders interested in building

There are no facts about the future. Leaders interested in building

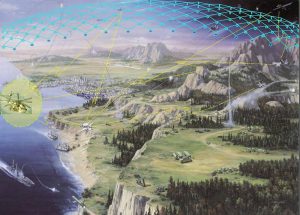

1. Contested in all domains (air, land, sea, space, and cyber). Increased lethality, by virtue of

1. Contested in all domains (air, land, sea, space, and cyber). Increased lethality, by virtue of

3. Trans-regional, gray zone, and hybrid strategies with both regular and irregular forces, criminal elements, and terrorists attacking our weaknesses and mitigating our advantages. The ensuing spectrum of competition will range from peaceful, legal activities through violent, mass upheavals and civil wars to traditional state-on-state, unlimited warfare.

3. Trans-regional, gray zone, and hybrid strategies with both regular and irregular forces, criminal elements, and terrorists attacking our weaknesses and mitigating our advantages. The ensuing spectrum of competition will range from peaceful, legal activities through violent, mass upheavals and civil wars to traditional state-on-state, unlimited warfare.

2. What signature does this system present to an adversary? It is difficult to hide on the future battlefield and temporary windows of advantage will require formations to reduce their battlefield signatures. Capabilities that require constant multi-directional broadcast and units with large mission command centers will quickly be targeted and neutralized.

2. What signature does this system present to an adversary? It is difficult to hide on the future battlefield and temporary windows of advantage will require formations to reduce their battlefield signatures. Capabilities that require constant multi-directional broadcast and units with large mission command centers will quickly be targeted and neutralized.

5. How does this capability help win in competition short of conflict with a near peer competitor? Near peer competitors will seek to achieve limited objectives

5. How does this capability help win in competition short of conflict with a near peer competitor? Near peer competitors will seek to achieve limited objectives

[Editor’s Note: The following post addresses the Era of Contested Equality (2035-2050) and is extracted from the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) G-2’s

[Editor’s Note: The following post addresses the Era of Contested Equality (2035-2050) and is extracted from the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) G-2’s  Changes encountered during the Future Operational Environment’s Era of Accelerated Human Progress (the present through 2035) begin a process that will re-shape the global security situation and fundamentally alter the

Changes encountered during the Future Operational Environment’s Era of Accelerated Human Progress (the present through 2035) begin a process that will re-shape the global security situation and fundamentally alter the  Post-World War II liberal order and assert or dispute regional alternatives to established global norms. State and non-state actors compete for power and control, often below the threshold of traditional armed conflict – or shield and protect their activities under the aegis of escalatory WMD,

Post-World War II liberal order and assert or dispute regional alternatives to established global norms. State and non-state actors compete for power and control, often below the threshold of traditional armed conflict – or shield and protect their activities under the aegis of escalatory WMD,  It is not clear whether the

It is not clear whether the  mid-Century, while other states, and combinations of states will rise and fall as challengers during the 2035-2050 timeframe. The security environment in this period will be characterized by conditions that will facilitate competition and conflict among rivals, and lead to endemic strife and warfare, and will have several defining features.

mid-Century, while other states, and combinations of states will rise and fall as challengers during the 2035-2050 timeframe. The security environment in this period will be characterized by conditions that will facilitate competition and conflict among rivals, and lead to endemic strife and warfare, and will have several defining features. identity politics will challenge global governance and broader globalization, with both collective security and globalism in decline. States share their strategic environments with networked societies which increasingly circumvent governments unresponsive to their citizens’ needs. Many states will face challenges from insurgents and global identity networks – ethnic, religious, regional, social, or economic – which either resist state authority or ignore it altogether.

identity politics will challenge global governance and broader globalization, with both collective security and globalism in decline. States share their strategic environments with networked societies which increasingly circumvent governments unresponsive to their citizens’ needs. Many states will face challenges from insurgents and global identity networks – ethnic, religious, regional, social, or economic – which either resist state authority or ignore it altogether. This diffusion of knowledge and capability and the aforementioned erosion of long-term collective security will lead to the formation of

This diffusion of knowledge and capability and the aforementioned erosion of long-term collective security will lead to the formation of