[Editor’s Note: Army Mad Scientist is pleased to feature today’s guest post — a semi-finalist from our Mad Scientist Writing Contest on the 4C’s: Competition, Crisis, Conflict, and Change. MAJ James P. Micciche and CW3 Nick Rife‘s submission tackled both of our contest’s writing prompts:

-

-

How will our competitors deny the U.S. Joint Force’s tactical, operational, and strategic advantages to achieve their objectives (i.e., win without fighting) in the Competition and Crisis Phases?

How will our competitors deny the U.S. Joint Force’s tactical, operational, and strategic advantages to achieve their objectives (i.e., win without fighting) in the Competition and Crisis Phases?

-

-

-

- How will our adversaries seek to overmatch or counter U.S. Joint Force strengths in future Large Scale Combat Operations?

-

… providing us with a scenario where the U.S. Joint Force squeaks out a tactical victory in large scale combat operations after effectively ceding the competition phase to a thinly veiled adversary. Today’s authors cogently build upon the case previously advocated by guest bloggers Dr. Russell Glenn and Ian Sullivan — that our adversaries are outflanking us via sub-threshold maneuver, and investing billions of dollars into new exquisite combat systems to achieve lasting overmatch is not a panacea. MAJ Micciche and CW3 Rife convincingly argue the folly of “investing in only platform-based capabilities” and that “Every day ceded in the competitive space is a day closer to a defeat in conflict.” Read on and heed the lessons contained therein!]

Context

The 2017 National Security Strategy is best known for codifying what it describes as a “return to great power competition (GPC),” and overtly naming existential geopolitical rivals or, Revisionist Powers. The 2017 NSS will be remembered as the catalyst for a series of ill-advised programs and unproductive efforts the greater U.S. Government (USG) implemented to address the opaque concept of GPC. A decade of U.S.-led unipolar hegemony followed by twenty years of foreign policy focused on non-state actors in the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT) left the U.S. under-prepared to address the complex challenges ‘great powers’ present to U.S. interests across all elements of national power. The proclivity to misinterpret the modern strategic environment, rival agents, and their objectives results from substantial variances in the strategic underpinnings of the U.S. and its modern rivals. United States foreign policy and security strategies often present narrow and limited perspectives of the international system, while rivals understand and operationalize a broader concept of competition and plan along far greater time horizons. The two systems are not only different but incompatible within game theory, as attempting to leverage finite logic in an infinite game leads to failure. Until the recent adoption of the nonlinear competition continuum in Joint Doctrine Note 1-19, U.S. military doctrine

The 2017 National Security Strategy is best known for codifying what it describes as a “return to great power competition (GPC),” and overtly naming existential geopolitical rivals or, Revisionist Powers. The 2017 NSS will be remembered as the catalyst for a series of ill-advised programs and unproductive efforts the greater U.S. Government (USG) implemented to address the opaque concept of GPC. A decade of U.S.-led unipolar hegemony followed by twenty years of foreign policy focused on non-state actors in the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT) left the U.S. under-prepared to address the complex challenges ‘great powers’ present to U.S. interests across all elements of national power. The proclivity to misinterpret the modern strategic environment, rival agents, and their objectives results from substantial variances in the strategic underpinnings of the U.S. and its modern rivals. United States foreign policy and security strategies often present narrow and limited perspectives of the international system, while rivals understand and operationalize a broader concept of competition and plan along far greater time horizons. The two systems are not only different but incompatible within game theory, as attempting to leverage finite logic in an infinite game leads to failure. Until the recent adoption of the nonlinear competition continuum in Joint Doctrine Note 1-19, U.S. military doctrine  utilized a binary construct of war or peace to describe bilateral relations between the United States and other nations. This dichotomy leads the U.S. to an over reliance on a singular instrument of national power (military force) to achieve its foreign policy objectives and protect its interests, a concern that the March 2021 Interim National Security Strategic Guidance directly addresses.

utilized a binary construct of war or peace to describe bilateral relations between the United States and other nations. This dichotomy leads the U.S. to an over reliance on a singular instrument of national power (military force) to achieve its foreign policy objectives and protect its interests, a concern that the March 2021 Interim National Security Strategic Guidance directly addresses.

Challenges associated with strategic group think manifest in several ways, the most germane has roots in Napoleonic era strategists. Theorists including Antoine Henry-Jomini (1779-1869)

Challenges associated with strategic group think manifest in several ways, the most germane has roots in Napoleonic era strategists. Theorists including Antoine Henry-Jomini (1779-1869)  and Carl von Clausewitz (1780-1831), who heavily influence U.S. military doctrine and professional education, predicate their strategic concepts on short-term sequential, rather than cumulative and complementing strategies within a perpetually evolving strategic environ. This feeds a perception that the U.S. can overcome competitive challenges by deterring rival aggression through a series of unilateral investments in instruments of military force. No greater example of this strategic deficiency exists than that of renewed focus on GPC through investing only in

and Carl von Clausewitz (1780-1831), who heavily influence U.S. military doctrine and professional education, predicate their strategic concepts on short-term sequential, rather than cumulative and complementing strategies within a perpetually evolving strategic environ. This feeds a perception that the U.S. can overcome competitive challenges by deterring rival aggression through a series of unilateral investments in instruments of military force. No greater example of this strategic deficiency exists than that of renewed focus on GPC through investing only in platform-based capabilities to expand military overmatch. An end state that even the Irregular Warfare Annex to the 2018 National Defense Strategy acknowledges “Encourages Adversaries to Pursue Indirect Approaches.” That is not to say the utility of force does not exist, but focusing only on the most dangerous course of action and ignoring the most likely is not only unwise, but also perilous.

platform-based capabilities to expand military overmatch. An end state that even the Irregular Warfare Annex to the 2018 National Defense Strategy acknowledges “Encourages Adversaries to Pursue Indirect Approaches.” That is not to say the utility of force does not exist, but focusing only on the most dangerous course of action and ignoring the most likely is not only unwise, but also perilous.

The most likely and ongoing course of action is adversaries seeking to achieve Master Sun’s pinnacle of military  excellence “breaking the enemy’s resistance without fighting” by leveraging cumulative and complementary long-term strategies to achieve a breadth of non-military options even in the face of military threat. Ultimately, this sets conditions to negate what is simultaneously the strength and weakness of the U.S. Joint Force – expeditionary military overmatch. Great powers, including China and Russia, understand how uncomfortable the United States is operating in the proverbial gray-zone of competition, but they have also witnessed the United States fail repeatedly in counterinsurgency, proxy wars, and other gray zone activities. By exploiting all instruments of national power in a long-term competitive mesh strategy predicated on restricting U.S. physical access and freedom of maneuver, rivals eventually establish conditions in crisis that restrict policymakers to a slew of ‘bad’ or ‘worse’ options. Every day ceded in the competitive space is a day closer to a defeat in conflict. The following scenario depicts how a theoretical

excellence “breaking the enemy’s resistance without fighting” by leveraging cumulative and complementary long-term strategies to achieve a breadth of non-military options even in the face of military threat. Ultimately, this sets conditions to negate what is simultaneously the strength and weakness of the U.S. Joint Force – expeditionary military overmatch. Great powers, including China and Russia, understand how uncomfortable the United States is operating in the proverbial gray-zone of competition, but they have also witnessed the United States fail repeatedly in counterinsurgency, proxy wars, and other gray zone activities. By exploiting all instruments of national power in a long-term competitive mesh strategy predicated on restricting U.S. physical access and freedom of maneuver, rivals eventually establish conditions in crisis that restrict policymakers to a slew of ‘bad’ or ‘worse’ options. Every day ceded in the competitive space is a day closer to a defeat in conflict. The following scenario depicts how a theoretical  peer threat might exploit U.S. strategic indifference to competition short of conflict by executing a layered strategy that systematically restricts the employment of U.S. instruments of national power.

peer threat might exploit U.S. strategic indifference to competition short of conflict by executing a layered strategy that systematically restricts the employment of U.S. instruments of national power.

Competition: 2017 – 2028

In 2017, the adversary establishes infrastructure development programs under the guise of a twenty-year plan to celebrate a ‘brave new world.’ The initiative, known as ‘One World One People’ (OWOP), seeks to develop critical  infrastructure in underdeveloped countries across the world. The investment projects include wireless and cellular networks, major rail projects, deep port maritime development, hydroelectric grid development, and mineral resource extraction. The regulation of ongoing pandemic and epidemic surges throughout the targeted continent opens windows of opportunity to invest in disaster relief that some begin to view as ‘hasty OWOP influence.’ In a sprint to react and conserve resources, state ministers of interior seek relief through broadening reliance on OWOP initiatives, including smart city development and autonomous systems health surveillance.

infrastructure in underdeveloped countries across the world. The investment projects include wireless and cellular networks, major rail projects, deep port maritime development, hydroelectric grid development, and mineral resource extraction. The regulation of ongoing pandemic and epidemic surges throughout the targeted continent opens windows of opportunity to invest in disaster relief that some begin to view as ‘hasty OWOP influence.’ In a sprint to react and conserve resources, state ministers of interior seek relief through broadening reliance on OWOP initiatives, including smart city development and autonomous systems health surveillance.

As adversary investment grows into the spaces where the U.S. once enjoyed significant influence, a recalibration of language in the diplomatic sector and promised reforms in foreign direct investment follow. Though initially effective, U.S. influence wanes in light of nanotechnology and geo-engineering initiatives exported to theater in 2024 to combat agricultural failures. The move effectively monopolizes a maritime location of strategic importance once dominated by U.S. tourists and western corporations. Senior military leadership views adversary control of key maritime lanes as a threat to expeditionary reach, and in 2025 U.S. military littoral activity increases exponentially. Despite the shift in naval activity, U.S. maritime mobility precipitously diminishes; and with it, a relative amount of force projection.

Simultaneously, western academic circles criticize U.S. rhetoric toward multi-lateral investment initiatives. The arguments presented consist of the following: the investments yield positive results in developing spaces and U.S. foreign policy must redirect its position in the modern world to a more productive role. As a result, several leading think tanks conduct a comprehensive analysis on adversary-U.S. relations. The analysis concludes in 2026 and reinforces the  need for a ‘whole of government’ approach without drawing specific correlations to adversary investment in dual-use tech and strategic military reach – an oversight that would prove deadly in less than five years.

need for a ‘whole of government’ approach without drawing specific correlations to adversary investment in dual-use tech and strategic military reach – an oversight that would prove deadly in less than five years.

As domestic U.S. political differences widen through the mid-2020s, adversary military elements observe and act from afar employing increasingly effective disinformation operations. Leveraging bots and ‘deep fake’ analytics, adversary information warriors chomp at the bit to instigate a  modern Archduke Franz Ferdinand flashpoint that could lure rival military powers into conflict. The adversary nurtures its information warfare and cyber capabilities employing non-military contracts with state-run academia to proliferate and export weapons that are otherwise invisible to the common observer. Tensions between Revisionist Powers and Western allies continue to rise, and an overt dismantling of U.S. physical assets around the globe begins.

modern Archduke Franz Ferdinand flashpoint that could lure rival military powers into conflict. The adversary nurtures its information warfare and cyber capabilities employing non-military contracts with state-run academia to proliferate and export weapons that are otherwise invisible to the common observer. Tensions between Revisionist Powers and Western allies continue to rise, and an overt dismantling of U.S. physical assets around the globe begins.

Crisis: Six Months Ago

Almost half of the OWOP strategy reaches maturity by 2027, revealing select inclinations toward alternative and malign purposes. In early 2028, the projects reveal their true purpose – deep and shaping fires to set conditions within diplomatic, information, and economic sectors. Once adversary conditions are set, introduction of multi-domain military assets begins.

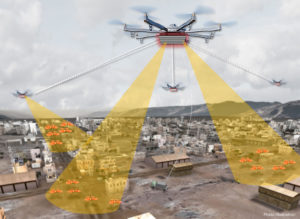

Adversary special operations forces emerge in several locations in a neighboring sovereign state. Sentiment analytics at an information warfare site in CONUS are first to provide indications and warnings, cueing additional strategic collect in the region. As all assets point at the theater of interest, the sinister nature of OWOP initiatives takes shape, and geographic combatant commanders scramble to sound the alarm. The adversary sets the theater to maintain standoff at the onset of foreign incursion into neighboring or waypoint states. Two years of tech integration in support of pandemic mitigation enables forward adversary elements to detect minor changes to the physical environment or electromagnetic spectrum in key terrain space. Flexible payloads on drone tech and a monopoly on commercial communications infrastructure make adversary presence ubiquitous without the necessity of physical presence.

As geographic combatant command staffs dust off contingency plans, a stark reality emerges: the Joint Force retains few strategic mobility options as a result of deliberately dismantling its influence infrastructure and physical military holdings in the mid-20s. Rail lines originally developed to connect major metro areas now seize assets to export, and introduce military capability into landlocked spaces. Maritime development conducted in the early phases of the OWOP initiative denies physical access and digital interoperability to which Joint and Coalition partners grew accustomed during the GWOT years.

As a crisis point erupts, the Joint Force faces limited options regarding how, where, and when they can deploy U.S. forces forward. This effect is not just the product of adversarial anti-access and area denial (A2AD) capabilities; it is the culmination of an incremental loss of physical ground and influence in the competition space years prior. Ports once vital to U.S. deployment plans are now owned, controlled, operated, or influenced by the adversary or its proxies.  OWOP member nations restrict U.S. overflight and strategic access for fear of reprisal from the adversary. Perhaps most damaging at the onset of the campaign, the lack of a coherent information strategy allows the adversary to paint the United States as the aggressor in local and international news media, which are both, by now, saturated with adversarial sympathizers. The adversary recognizes this as a key terrain space and executes both targeted and broad information operations, further restricting options afforded to U.S. policy makers. These constraints force U.S. Commanders to assume increasingly high levels of risk in their theater mobility plans, relying heavily on the small footprint of forward deployed Special Operations Forces (SOF) and Security Force Assistance (SFA) advisors. Even in the most optimistic scenario, the adversary skillfully executes a multi-tiered denial system that was a decade in the making. The result delays the deployment of U.S. forces, thereby allowing the adversary to set conditions that place its forces at a position of extreme advantage.

OWOP member nations restrict U.S. overflight and strategic access for fear of reprisal from the adversary. Perhaps most damaging at the onset of the campaign, the lack of a coherent information strategy allows the adversary to paint the United States as the aggressor in local and international news media, which are both, by now, saturated with adversarial sympathizers. The adversary recognizes this as a key terrain space and executes both targeted and broad information operations, further restricting options afforded to U.S. policy makers. These constraints force U.S. Commanders to assume increasingly high levels of risk in their theater mobility plans, relying heavily on the small footprint of forward deployed Special Operations Forces (SOF) and Security Force Assistance (SFA) advisors. Even in the most optimistic scenario, the adversary skillfully executes a multi-tiered denial system that was a decade in the making. The result delays the deployment of U.S. forces, thereby allowing the adversary to set conditions that place its forces at a position of extreme advantage.

With limited options on the table, strategic force mobility comes at a significant national cost that an already uncertain America public has a hard time tolerating.

Conflict: 2028-2035

Taking casualties before arriving to the Joint Operational Area (JOA), a U.S. Army Division eventually confronts the adversary in large-scale ground combat. The conventional force intelligence warfighting function has seconds to react to and predict enemy movement in support of target execution at speed. Natural language processing, graph, predictive, and geospatial algorithmic models are all optimized to extract targetable opportunities spread over Air Tasking Order (ATO) cycles, consequently destroying enemy capability. In addition to combined arms maneuver, adversary elements traverse the information space and employ specialized guerilla tactics that confound attribution. The adversary commander initiates electronic warfare (EW) attacks followed by drone swarm formations with multi-functional impacts to friendly elements. The most disruptive effects on the U.S. Division include loss of position assurance and broad-spectrum communications transport denial.

Taking casualties before arriving to the Joint Operational Area (JOA), a U.S. Army Division eventually confronts the adversary in large-scale ground combat. The conventional force intelligence warfighting function has seconds to react to and predict enemy movement in support of target execution at speed. Natural language processing, graph, predictive, and geospatial algorithmic models are all optimized to extract targetable opportunities spread over Air Tasking Order (ATO) cycles, consequently destroying enemy capability. In addition to combined arms maneuver, adversary elements traverse the information space and employ specialized guerilla tactics that confound attribution. The adversary commander initiates electronic warfare (EW) attacks followed by drone swarm formations with multi-functional impacts to friendly elements. The most disruptive effects on the U.S. Division include loss of position assurance and broad-spectrum communications transport denial.

The war of 2028 is both new and familiar.

Weather, terrain, and enemy decision cycles dictate friendly action, the familiar playbook of armed conflict. What is new to the Joint Force of present day is the onslaught of capability delivered in spaces unfamiliar to division-level  personnel attempting to leverage the enterprise and make sense of operations at the edge. Cyber operations, information warfare, dual-use battlefield-of-things tech, and the employment of hypersonic munitions are among the unfamiliar components within the conflict ecosystem.

personnel attempting to leverage the enterprise and make sense of operations at the edge. Cyber operations, information warfare, dual-use battlefield-of-things tech, and the employment of hypersonic munitions are among the unfamiliar components within the conflict ecosystem.

The friendly force maintains a singular distinctive advantage – it reduces reliance on fossil fuels in the course of its operations when compared to the early 2020s. The adversary retains no such advantage. Key to U.S. operational design is extending adversary logistics lines and destroying forward fuel points in order to limit adversary flexibility and theater mobility. Through its various modernization portfolios, the adversary never quite matures from an industrial sustainment model. Coalition formations exploit  this through wheeled autonomous systems with limited electromagnetic signatures and ground based position assurance. The challenge is to establish a narrative of moral high ground in the vicinity of the infrastructure from which adversary fossil fuel originates; a narrative long ago forfeited in U.S. policy.

this through wheeled autonomous systems with limited electromagnetic signatures and ground based position assurance. The challenge is to establish a narrative of moral high ground in the vicinity of the infrastructure from which adversary fossil fuel originates; a narrative long ago forfeited in U.S. policy.

The Division does not appear in the JOA by accident. Its role in support of the land component is a slow burn — one that initially exhausts alternative instruments of national power. SOF and Security Force Assistance Brigades (SFAB) operate as permanent fixtures in the spaces where competition turns to crisis, and crisis to conflict. Additionally, the use of SFABs enable the Joint Force to better incorporate partner forces into operations before the arrival of the main body of U.S. forces. Due to the delay in achieving strategic theater mobility, SFABs integrate with partner nation formations to enable the delivery of long-range multi-domain effects from outside the theater. Once coalition combat power arrives, SFABs integrate partner force knowledge of terrain and environment into U.S. planning processes, which enables the passage of lines to support offensive operations once coalition conditions are set.

As the fight transitions, the coalition continues to peel back adversary capabilities. The enemy approach consists of A2AD techniques to limit decisive engagement with coalition forces. Fortunately, at echelon, quick reaction data science teams execute predictive models based on terrain, weather, and adversary behavior to ascertain the most likely engagement areas for high value targets – physical spaces the adversary commander must retain to accomplish his mission. As a communications denied Division, it must conduct these operations ‘in the dark.’ The ability of allied forces to see their formations digitally in a multi-echelon sense is only as good as the last time it synchronized with the enterprise.

To regain space in the decision support template, the Joint Force Commander employs an SFAB battalion advising team as a deception. As a result, the adversary miscalculates. The battalion advising team is located with reliable partners with whom it usually interacts, but under the current circumstances, it becomes a critical asset for the Joint Force Commander. Two years prior, the advising team fields a ‘stay behind’ Multi-Domain Autonomous Defense  System (M-DADS) – a 40-foot containerized defensive capability consisting of fully automated quadrupeds, autonomous wheeled air defense assets, and tethered rotary UAS that cast spoof electromagnetic signatures at various ranges to confuse adversarial sensors. Relying on its newly developed target acquisitions, the adversary believes the signatures created by the SFAB team to be an opposing Armored Brigade Combat Team (ABCT). Once adversary weapon systems were calibrated to neutralize the ersatz ABCT, M-DADS counter-fire is engaged, increasing partner force survivability until the Joint Force Commander can engage the adversary with a more direct weapon solution.

System (M-DADS) – a 40-foot containerized defensive capability consisting of fully automated quadrupeds, autonomous wheeled air defense assets, and tethered rotary UAS that cast spoof electromagnetic signatures at various ranges to confuse adversarial sensors. Relying on its newly developed target acquisitions, the adversary believes the signatures created by the SFAB team to be an opposing Armored Brigade Combat Team (ABCT). Once adversary weapon systems were calibrated to neutralize the ersatz ABCT, M-DADS counter-fire is engaged, increasing partner force survivability until the Joint Force Commander can engage the adversary with a more direct weapon solution.

Achieving such a synergy of cross-functional technology de-synchronizes the adversary’s ability to employ the depth of his available assets, temporarily obscuring his understanding of the operational area.  This provides a window of opportunity for the Division to overmatch its opponent in capability, if only briefly. The Division edges out a tactical victory – onto the next element in the formation.

This provides a window of opportunity for the Division to overmatch its opponent in capability, if only briefly. The Division edges out a tactical victory – onto the next element in the formation.

Conclusion – 2035 and beyond

The U.S. must compete as aggressively as it fights because the conditions for victory in armed conflict are set by relationships and exchanges in competition/peace. Competing effectively in the military sense compels would-be adversaries to seek alternative courses of action across the observable depth of elements of national power. To correct the trajectory described in the scenario above, the U.S. must consider altering the weight of effort in the future strategic environment, or the likelihood of large scale combat increases as global U.S. influence decreases. Despite competition’s importance to its national interests and overall security, the United States must realize it cannot compete in an omnipresent manner and must prioritize where, when, and how it competes. In this zero sum game, the only loser is the one that does not play the game.

If you enjoyed this post, check out the following related content:

Blurring Lines Between Competition and Conflict

Sub-threshold Maneuver and the Flanking of U.S. National Security, by Dr. Russell Glenn

“Once More unto The Breach Dear Friends”: From English Longbows to Azerbaijani Drones, Army Modernization STILL Means More than Materiel, by Ian Sullivan

The Convergence: Hybrid Threats and Liminal Warfare with Dr. David Kilcullen, the associated podcast, and the video [access via a non-DoD network] and notes from Mad Scientist’s Operational Environment and Conflict over the Next Decade webinar on 19 January 2021, featuring Dr. T.X. Hammes. Dr. David Kilcullen, and Dr. Sean McFate

The Convergence: The Future of Ground Warfare with COL Scott Shaw, and associated podcast

Warfare in the Parallel Cambrian Age, by Chris O’Connor

… explore two visions of large scale combat operations in the future with our Pacing Threat:

“No Option is Excluded” — Using Wargaming to Envision a Chinese Assault on Taiwan, by Ian Sullivan

The U.S. Joint Force’s Defeat before Conflict, by CPT Anjanay Kumar

… learn more about our Pacing Threat and its activities across the Competition, Crisis, and Conflict spectrum:

China: Our Emergent Pacing Threat

Competition in 2035: Anticipating Chinese Exploitation of Operational Environments

Disinformation, Revisionism, and China with Doowan Lee and the associated podcast

China’s PLA Modernization through the DOTMLPF-P Lens, by Dr. Jacob Barton

Competition and Conflict in the Next Decade

Disrupting the “Chinese Dream” – Eight Insights on how to win the Competition with China

China: “New Concepts” in Unmanned Combat and Cyber and Electronic Warfare

ATP 7-100.3, Chinese Tactics; TRADOC G-2’s China Tri-fold; the China products page; and information on PLA weapon systems accessed via the Worldwide Equipment Guide (WEG) on the OE Data Integration Network (ODIN).

… and review the U.S. Army’s single consistent OE narrative (spanning the near, mid-, and far terms out to 2050) further with the following content:

Four Models of the Post-COVID World, The Operational Environment: Now through 2028, and The 2 + 3 Threat video

The Future Operational Environment: The Four Worlds of 2035-2050, the complete AFC Pamphlet 525-2, Future Operational Environment: Forging the Future in an Uncertain World 2035-2050, and associated video

About the Authors:

MAJ James P. Micciche is an Army Strategist (FA59) and the G5 at the Security Forces Assistance Command (SFAC). He has deployment and service experience in the Middle East, Africa, Afghanistan, Europe, and Indo-Pacific. He holds degrees from the Fletcher School at Tufts University and Troy University. He can be reached on Twitter @james_micciche.

Chief Warrant Officer 3 Nick Rife is the senior intelligence technician for 2nd Security Force Assistance Brigade. He has service experience in the Middle East, Europe and Southwest Asia. He has previously served at U.S. Army Forces Command G-2 as the principal developer of the Digital Intelligence Systems Master Gunner Course, fusion chief at 82nd Airborne Division G-2, and 4th Brigade Combat Team, 82nd Airborne Division.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).