[Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist Laboratory is pleased to publish today’s post by returning guest blogger and proclaimed Mad Scientist Marie Murphy, exploring the evolving role of nation-states in an increasingly multipolar world. While nations-states will persevere as the primary actors in the international system for the foreseeable future, their dominion will increasingly be challenged by the growing wealth and influence of multi-national corporations (MNCs) and the emergence of on-line communities of interest coalescing beyond traditional concepts of nationality and fidelity. Given the resultant diffusion of power and allegiance, the dynamics of competition and conflict may well morph beyond our current concepts of allies, strategic competitors, and large scale combat operations. Ms. Murphy posits two scenarios and then explores the associated ramifications of this evolving power dynamic for the U.S. Army — Enjoy!]

It’s a human fallacy to believe that things in the present have always been and always will be.1 Of course, history books confirm that this is not the case, but it is difficult to imagine living in a world other than the one we’ve adjusted to today.  We are all familiar with the current structure of international power, but nation-states as we know them are a relatively new concept. The “official” creation date for what is considered the modern nation-state is often pinned at the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.2 However, it wasn’t until the end of WWII and the subsequent redefining of territory in Africa and the Middle East that the modern map began to appear. The fall of the USSR in 1991 redrew the map again, adding new states in Eastern Europe, the

We are all familiar with the current structure of international power, but nation-states as we know them are a relatively new concept. The “official” creation date for what is considered the modern nation-state is often pinned at the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.2 However, it wasn’t until the end of WWII and the subsequent redefining of territory in Africa and the Middle East that the modern map began to appear. The fall of the USSR in 1991 redrew the map again, adding new states in Eastern Europe, the  Caucasus, and Central Asia. These major shifts occurred within the lifetimes of people today, demonstrating that the current world order is anything but set in stone.

Caucasus, and Central Asia. These major shifts occurred within the lifetimes of people today, demonstrating that the current world order is anything but set in stone.

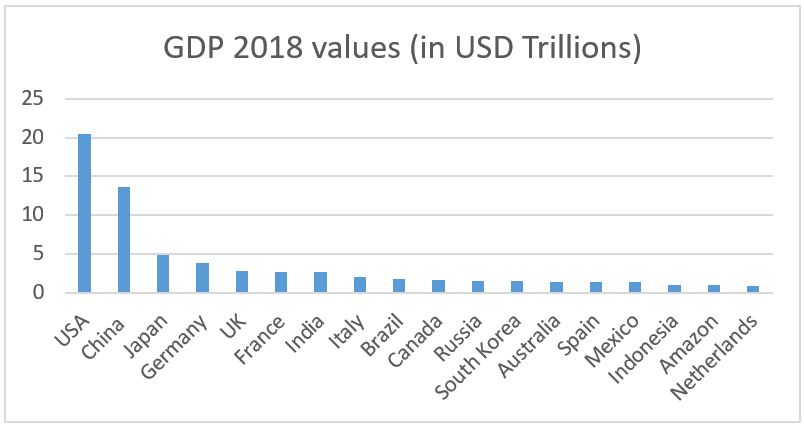

There are several emerging factors which may come to threaten the recent primacy of the nation-state in the distribution of global power as it currently stands, including the resurgence of multi-national corporations (MNCs) and the proliferation of online organizations, both aided by the technological advances of the 21st century. MNCs and online organizations connect people around the world and transcend national boundaries. They are capable of amassing capital and influence comparable to that of some nation-states, creating a potential shift in global power dynamics. For example, in 2018, Amazon topped $1 Trillion in value, placing it 17th in the world amongst nation-states in terms of GDP.3

Today, MNCs such as Apple and Amazon rely on global stability to maintain optimal operations. Conflicts affect companies by threatening the interruption or loss of crucial supply chains and the diversion of workers. Due to these potential disruptions, MNCs may have an interest in discouraging, reducing, and restricting conflict and some have the capital to attempt to do so. On the other hand, not all corporate intervention in conflict spaces could prove benevolent. Companies could partner with competing parties in a conflict or further exacerbate divisions by involving their own private security forces. The consequences of kinetic intervention by MNCs may prove detrimental, especially if it disrupts the production and distribution of critical natural resources or the economic livelihoods of the local population that depend on its peaceful presence.4 As the global influence of MNCs rises, the U.S. Army may face questions such as: Could conflict that poses a potential disruption to private industry be mitigated by that industry? Could industry be a major player in conflict zones?

The potential rise of individual allegiances and ideologies beginning to align more with virtual communities, which do not recognize international borders, may start to erode the cultural and political bonds of a nation-state. One example of a diverse online community is Facebook, which currently stands as a platform for like-minded people to join groups and pages according to their personal interests.

But could this be taken to the next level? Facebook recently announced the potential launch of its own digital currency. While many consider this technology to be ahead of its time, and definitely ahead of regulatory standards, it may be a signal that online entities will be capable of encroaching upon what has historically been a governmental responsibility.5 As online organizations develop and proliferate, questions pertinent to national defense begin to emerge, including: Could a nation suffering from ideological dissolution still field a physical army? Could an online organization with multinational membership present a cyber threat to armed forces around the world? Could an online community create its own army not based on geography and borders, but on shared belief?

But could this be taken to the next level? Facebook recently announced the potential launch of its own digital currency. While many consider this technology to be ahead of its time, and definitely ahead of regulatory standards, it may be a signal that online entities will be capable of encroaching upon what has historically been a governmental responsibility.5 As online organizations develop and proliferate, questions pertinent to national defense begin to emerge, including: Could a nation suffering from ideological dissolution still field a physical army? Could an online organization with multinational membership present a cyber threat to armed forces around the world? Could an online community create its own army not based on geography and borders, but on shared belief?

So, where do these current and potential developments leave nation-states? I have chosen to highlight two possible future scenarios which may emerge from the rising influence of MNCs and online organizations: a multipolar power distribution and a devolving status quo.

The world may be evolving into a multipolar system comprised of different nodes of power; where nation-states, MNCs, and online organizations operate on a more even global playing field. MNCs may begin to leverage their high levels of capital, resources, and influence to impact international and military affairs  beyond the oversight of a government. A company’s entrenchment in a region or domain where conflict is developing may be sufficient grounds for direct involvement. If the company exerts more power than the government in that area, it may take on the roles and responsibilities of either mitigating or managing that conflict, possibly including the use of private forces or the co-opting of the legitimate military. Large and diverse online organizations begin to fray the social fabric of established nation-states as citizens’ lives increasingly move and are lived online. These organizations may develop the social organizational capacity that governments used to exclusively possess; the ability to coordinate the mass movement or participation of a large number of people or to control society in other ways, such as holding and managing their currency. In this scenario, nation-states play a somewhat diminished role as what used to be exclusively state-held power is now dispersed among various relevant international organizations.

beyond the oversight of a government. A company’s entrenchment in a region or domain where conflict is developing may be sufficient grounds for direct involvement. If the company exerts more power than the government in that area, it may take on the roles and responsibilities of either mitigating or managing that conflict, possibly including the use of private forces or the co-opting of the legitimate military. Large and diverse online organizations begin to fray the social fabric of established nation-states as citizens’ lives increasingly move and are lived online. These organizations may develop the social organizational capacity that governments used to exclusively possess; the ability to coordinate the mass movement or participation of a large number of people or to control society in other ways, such as holding and managing their currency. In this scenario, nation-states play a somewhat diminished role as what used to be exclusively state-held power is now dispersed among various relevant international organizations.

Alternatively, nation-states may continue to hold the majority of global power, but the massive capital and influence of MNCs and online organizations could grow to become at odds with governments and these groups may vie for a seat at the table. A devolved version of the present may manifest in the event of increased isolationism as large companies lobby their governments to do business worldwide while leaders prefer more domestically focused economic thinking.  Online organizations may overtake governments in cultural leadership, leaving governments to be little more than administrative units while citizens who live next door to each other have allegiances to groups and organizations formed from people from all over the world. These online groups may eventually take on governmental responsibilities as well (such as taxation used to provide services) and have the capability to incite mass mobility at a moment’s notice.

Online organizations may overtake governments in cultural leadership, leaving governments to be little more than administrative units while citizens who live next door to each other have allegiances to groups and organizations formed from people from all over the world. These online groups may eventually take on governmental responsibilities as well (such as taxation used to provide services) and have the capability to incite mass mobility at a moment’s notice.

Combatting these potential changes in the international balance of power poses new challenges for the Army. Either of these scenarios could alter ally/competitor relationships. Alliances might shift due to either economic interests or ideological priorities. Such considerations may supersede geostrategic factors in a historically symbiotic alliance. The need for American protection and military assistance might not be as great if current power competitors no longer hold that same power or demonstrate a shift in interests.

An evolving power dynamic would alter the way that the Army thinks about its concepts and structures its force. In the future, MNCs may be “another player on the field,” both domestically through lobbying and political influence and in theater due to their operations or investments on the ground. This entanglement of military objectives and private industry interests may demand greater consideration as corporations continue to drive economic development and  growth worldwide. Online organizations may divert critical human resources away from patriotic causes towards ones that fulfill specific personal ideologies which may not align with the Nation and the Army. Based on economic and technological advancements, the Army may find itself with different established allies and in the company of states and organizations whose interests and capabilities temporarily align with the U.S. The role of a nation-state in the global order may be evolving as other powerful players come to the table. Whether or not these players will be integrated, or are too big not to be, is yet to be seen.

growth worldwide. Online organizations may divert critical human resources away from patriotic causes towards ones that fulfill specific personal ideologies which may not align with the Nation and the Army. Based on economic and technological advancements, the Army may find itself with different established allies and in the company of states and organizations whose interests and capabilities temporarily align with the U.S. The role of a nation-state in the global order may be evolving as other powerful players come to the table. Whether or not these players will be integrated, or are too big not to be, is yet to be seen.

If you enjoyed this post, please see:

– Virtual Nations: An Emerging Supranational Cyber Trend, also by Marie Murphy

– Splinternets, by Howard Simkin

– Alternet: What Happens When the Internet is No Longer Trusted? by LtCol Jennifer “JJ” Snow

Proclaimed Mad Scientist Marie Murphy is a senior at The College of William and Mary in Virginia, studying International Relations and Arabic. She is a regular contributor to the Mad Scientist Laboratory, interned at Headquarters, U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) with the Mad Scientist Initiative during the summer of 2018, and is currently serving as a Mad Scientist Initiative consultant. She was a Research Fellow for William and Mary’s Project on International Peace and Security.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article do not imply endorsement by the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, the Army Futures Command, the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This piece is meant to be thought-provoking and does not reflect the current position of the U.S. Army.

1 Bartlett, Jamie. “Return of the City-State,” Aeon, September 5, 2017. https://aeon.co/essays/the-end-of-a-world-of-nation-states-may-be-upon-us

2 “Peace of Westphalia (1648),” Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199743292/obo-9780199743292-0073.xml

3 “Gross Domestic Product 2018,” World Bank, 2018. https://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/GDP.pdf

Streitfield, David. “Amazon Hits $1,000,000,000,000 in Value, Following Apple,” The New York Times, Sept. 4, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/04/technology/amazon-stock-price-1-trillion-value.html

4 Humphreys, Macartan. “Economics and Violent Conflict,” Harvard University, 2003. https://www.unicef.org/socialpolicy/files/Economics_and_Violent_Conflict.pdf

5 Sprouse, William. “Facebook Says Libra Digital Currency May Never Launch,” CFO, July 30, 2019. https://www.cfo.com/regulation/2019/07/facebook-says-libra-digital-currency-may-never-launch/

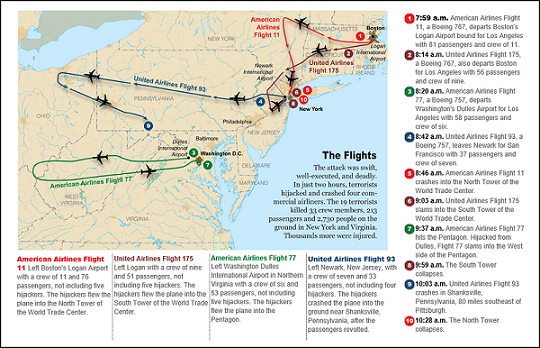

A loud buzz pierced the quiet night air. A group of drones descended on a chemical plant near New York City. The drones disperse throughout the installation in search of storage tanks. A few minutes later, the buzz of the drone propellers was drowned out by loud explosions. A surge of fire leapt to the sky. A plume of gas followed, floating towards the nearby city. The gas killed thousands and thousands more were hospitalized with severe injuries.

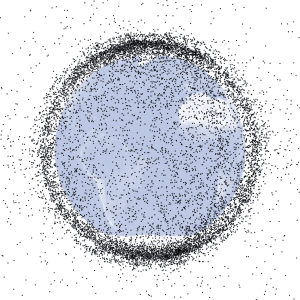

A loud buzz pierced the quiet night air. A group of drones descended on a chemical plant near New York City. The drones disperse throughout the installation in search of storage tanks. A few minutes later, the buzz of the drone propellers was drowned out by loud explosions. A surge of fire leapt to the sky. A plume of gas followed, floating towards the nearby city. The gas killed thousands and thousands more were hospitalized with severe injuries.  Drones offer terrorists low cost methods of delivering harm with lower risk to attacker lives. Drone attacks can be launched from afar, in a hidden position, close to an escape route. Simple unmanned systems can be acquired easily: Amazon.com offers seemingly hundreds of drones for as low as $25. Of course, low cost drones also mean lower payloads that limit the harm caused, often significantly. Improvements to drone autonomy will allow terrorists to deploy more drones at once, including in true drone swarms.

Drones offer terrorists low cost methods of delivering harm with lower risk to attacker lives. Drone attacks can be launched from afar, in a hidden position, close to an escape route. Simple unmanned systems can be acquired easily: Amazon.com offers seemingly hundreds of drones for as low as $25. Of course, low cost drones also mean lower payloads that limit the harm caused, often significantly. Improvements to drone autonomy will allow terrorists to deploy more drones at once, including in true drone swarms. oil production capacity.

oil production capacity. potential still exists for significant harm. Terrorists can strike popular tourist sites like the Statue of Liberty or San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf. U.S. military vessels are ideal targets too, such as the USS Cole bombing in October 2000.

potential still exists for significant harm. Terrorists can strike popular tourist sites like the Statue of Liberty or San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf. U.S. military vessels are ideal targets too, such as the USS Cole bombing in October 2000. aroochy Shire, Australia, and released hundreds of thousands of gallons of raw sewage into the surrounding area.

aroochy Shire, Australia, and released hundreds of thousands of gallons of raw sewage into the surrounding area.

Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT).

Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT).

There are efforts, such as University of Texas-Austin’s tool

There are efforts, such as University of Texas-Austin’s tool

In retrospect, it may have been one of the most ironic moments of the Cold War. Early in Dwight Eisenhower’s first term, during a meeting of the National Security Council, the President asked his advisors to propose an economic strategy to counter the emerging global threat posed by Soviet foreign economic policies. Not only were the Russians promoting their rapid industrialization model to foreign governments, the Marxist ideology that supported it was proving increasingly attractive to anti-colonial movements around the world. European empires were in full retreat, leaving a void the communists were eager to fill.

In retrospect, it may have been one of the most ironic moments of the Cold War. Early in Dwight Eisenhower’s first term, during a meeting of the National Security Council, the President asked his advisors to propose an economic strategy to counter the emerging global threat posed by Soviet foreign economic policies. Not only were the Russians promoting their rapid industrialization model to foreign governments, the Marxist ideology that supported it was proving increasingly attractive to anti-colonial movements around the world. European empires were in full retreat, leaving a void the communists were eager to fill. Eisenhower believed Western liberal democratic ideals, and the free enterprise and open trade that supported them, were under direct threat. The United States confronted a new “Era of Contested [Strategic] Equality.”

Eisenhower believed Western liberal democratic ideals, and the free enterprise and open trade that supported them, were under direct threat. The United States confronted a new “Era of Contested [Strategic] Equality.” The grand irony of that moment was that the best strategy proved to be no strategy at all. Less than forty years later, the Soviet economic model was so discredited it had lost its global appeal. It had even contributed to the collapse of the Soviet Union itself. Free trade and private enterprise proliferated around the world, leading to an era of growth and prosperity unprecedented in history. Communist countries, even China, were rushing to emulate capitalist success. The American economic model had proven superior without any strategy whatsoever. It was such a decisive repudiation of the Marxist material dialectic—the inevitable march of history toward communism—that Soviet ideology would never again pose an existential threat to Western democracies. All Eisenhower really needed was time.

The grand irony of that moment was that the best strategy proved to be no strategy at all. Less than forty years later, the Soviet economic model was so discredited it had lost its global appeal. It had even contributed to the collapse of the Soviet Union itself. Free trade and private enterprise proliferated around the world, leading to an era of growth and prosperity unprecedented in history. Communist countries, even China, were rushing to emulate capitalist success. The American economic model had proven superior without any strategy whatsoever. It was such a decisive repudiation of the Marxist material dialectic—the inevitable march of history toward communism—that Soviet ideology would never again pose an existential threat to Western democracies. All Eisenhower really needed was time. The first term, Kairos, comes from the ancient Greek. Unlike chronos, a linear measure of time, kairos has a qualitative meaning. It considers context, for example “a time for every purpose under heaven.” Most commonly understood as momentary opportunity, it also describes a season of exigence, or the right thing(s) at the right time in the right measure. Within the realm of international competition, it can be understood as an era – one of national power and ascendancy, or the perpetuation and defense of national identity or a set of ideals.

The first term, Kairos, comes from the ancient Greek. Unlike chronos, a linear measure of time, kairos has a qualitative meaning. It considers context, for example “a time for every purpose under heaven.” Most commonly understood as momentary opportunity, it also describes a season of exigence, or the right thing(s) at the right time in the right measure. Within the realm of international competition, it can be understood as an era – one of national power and ascendancy, or the perpetuation and defense of national identity or a set of ideals. Sthenos is the strength of will and purpose derived from moral character and energy. The familiar word calisthenic employs the term with regard to physical conditioning and beauty as well as the need to be disciplined in their pursuit. Sthenos combines psychological and physical strength. Thus, individuals, groups, and nations with more energy and determination have superior strength, compared to those with less.

Sthenos is the strength of will and purpose derived from moral character and energy. The familiar word calisthenic employs the term with regard to physical conditioning and beauty as well as the need to be disciplined in their pursuit. Sthenos combines psychological and physical strength. Thus, individuals, groups, and nations with more energy and determination have superior strength, compared to those with less. geography, or natural resources as the primary, even deterministic, sources of a nation’s timestrength.

geography, or natural resources as the primary, even deterministic, sources of a nation’s timestrength. The Cold War strategic environment highlighted the importance of this economic competition. A central question during this century will be whether economic strength proves decisive once again.

The Cold War strategic environment highlighted the importance of this economic competition. A central question during this century will be whether economic strength proves decisive once again.

Perhaps it was cultural determination, even amid setbacks, that propelled American economic performance over the past two centuries. China’s rapid economic development, and Chinese culture, may yet be tested in this regard.

Perhaps it was cultural determination, even amid setbacks, that propelled American economic performance over the past two centuries. China’s rapid economic development, and Chinese culture, may yet be tested in this regard. The Cold War is over, but it is almost certain that we are moving into another Era of Contested Equality. If so, which nation or alliance will hold the edge in kairosthenic power? Will China’s ethnic nationalism and economic model prove

The Cold War is over, but it is almost certain that we are moving into another Era of Contested Equality. If so, which nation or alliance will hold the edge in kairosthenic power? Will China’s ethnic nationalism and economic model prove  superior over time, or do they contain subtle strategic weaknesses? With the many new challenges of the 21st Century, including technological convergence and the rise of peer competitors, the United States would be wise to remember that its kairosthenic competitiveness will be determined by more than economic or military policies.

superior over time, or do they contain subtle strategic weaknesses? With the many new challenges of the 21st Century, including technological convergence and the rise of peer competitors, the United States would be wise to remember that its kairosthenic competitiveness will be determined by more than economic or military policies.

But the U.S. tends to think more conventionally about future conflict, in part because it has been able to rest on technological superiority for so long. Now, though, it must think differently. Isaac Asimov offers a path toward new strategic solutions through creativity, a process that can be mastered by “becoming dissatisfied” with the current state of “knowledge” and then “rejecting” some or all of it for new approaches.

But the U.S. tends to think more conventionally about future conflict, in part because it has been able to rest on technological superiority for so long. Now, though, it must think differently. Isaac Asimov offers a path toward new strategic solutions through creativity, a process that can be mastered by “becoming dissatisfied” with the current state of “knowledge” and then “rejecting” some or all of it for new approaches. Innovation continually underperforms in part because it is the follow-on to ideas, not the precursor, and because it results in solutions for the tactical level of war. Previous eras of transformational change, however, required societies to tackle “primarily intellectual, not technical” challenges.

Innovation continually underperforms in part because it is the follow-on to ideas, not the precursor, and because it results in solutions for the tactical level of war. Previous eras of transformational change, however, required societies to tackle “primarily intellectual, not technical” challenges.

Take

Take