(Editor’s Note: The Mad Scientist Laboratory is pleased to present the following guest blog post from Mr. Ian Sullivan.)

During the past year, the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) G-2 has learned a great deal more about the Future Operational Environment (OE). While the underlying assessment of the OE’s trajectory has not changed,  as reported in last year’s The Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Future Warfare, we have learned a number of critical lessons and insights that affect Army doctrine, training, and modernization efforts. These findings have been captured in Assessing the Operational Environment: What We Learned Over the Past Year, published in Small Wars Journal last week. This post extracts and highlights key themes from this article.

as reported in last year’s The Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Future Warfare, we have learned a number of critical lessons and insights that affect Army doctrine, training, and modernization efforts. These findings have been captured in Assessing the Operational Environment: What We Learned Over the Past Year, published in Small Wars Journal last week. This post extracts and highlights key themes from this article.

General Lessons Learned:

We have confirmed our previous analysis of trends and factors that are intensifying and accelerating the transformation of the OE. The rapid innovation, development, and fielding of new technologies promises to radically enhance our abilities to live, create, think, and prosper. The accelerated pace of human interaction and widespread connectivity through the Internet of Things (IoT), and the concept of convergence are also factors affecting these trends. Convergence of societal trends and technologies will create new capabilities or societal implications that are greater than the sum of their individual parts, and at times are unexpected.

We have confirmed our previous analysis of trends and factors that are intensifying and accelerating the transformation of the OE. The rapid innovation, development, and fielding of new technologies promises to radically enhance our abilities to live, create, think, and prosper. The accelerated pace of human interaction and widespread connectivity through the Internet of Things (IoT), and the concept of convergence are also factors affecting these trends. Convergence of societal trends and technologies will create new capabilities or societal implications that are greater than the sum of their individual parts, and at times are unexpected.

This convergence will embolden global actors to challenge US interests. The perceived waning of US military power in conjunction with the increase in capabilities resulting from our adversaries’ rapid proliferation of technology and increased investment in research and development has set the stage for challengers to pursue interests contrary to America’s.

This convergence will embolden global actors to challenge US interests. The perceived waning of US military power in conjunction with the increase in capabilities resulting from our adversaries’ rapid proliferation of technology and increased investment in research and development has set the stage for challengers to pursue interests contrary to America’s.

We will face peer, near-peer, and regional hegemons as adversaries, as well as non-state actors motivated by identity, ideology, or interest, and individuals super-empowered by technologies and capabilities once found only among nations. They will directly attack our national will with cyber and sophisticated information operations.

We will face peer, near-peer, and regional hegemons as adversaries, as well as non-state actors motivated by identity, ideology, or interest, and individuals super-empowered by technologies and capabilities once found only among nations. They will directly attack our national will with cyber and sophisticated information operations.

Technologies in the future OE will be disruptive, smart, connected, and self-organizing. Key technologies, once thought to be science fiction, present new opportunities for military operations ranging from human operated / machine-assisted, to human-machine hybrid operations, to human-directed / machine-conducted operations; all facilitated by autonomy, Artificial Intelligence (AI), robotics, enhanced human performance, and advanced computing.

Technologies in the future OE will be disruptive, smart, connected, and self-organizing. Key technologies, once thought to be science fiction, present new opportunities for military operations ranging from human operated / machine-assisted, to human-machine hybrid operations, to human-directed / machine-conducted operations; all facilitated by autonomy, Artificial Intelligence (AI), robotics, enhanced human performance, and advanced computing.

Tactical Lessons Learned:

The tactical lessons we have learned reveal tangible realities found on battlefields around the globe today and our assessments about the future rooted in our understanding of the current OE. Our adversaries already are using weapons and systems that in some cases are superior to our own, providing selective overmatch of some US capabilities, such as long-range fires, air-defense, and electronic warfare. Commercial-off-the shelf (COTS) technologies are being used to rapidly create new and novel methods of warfare  (the most ubiquitous are drones and robotics that have been particularly successful in Iraq, Syria, and Ukraine). Our adversaries will often combine technologies or operating principles to create innovative methods of attack, deploying complex combinations of capabilities that create unique challenges to the Army and Joint Forces.

(the most ubiquitous are drones and robotics that have been particularly successful in Iraq, Syria, and Ukraine). Our adversaries will often combine technologies or operating principles to create innovative methods of attack, deploying complex combinations of capabilities that create unique challenges to the Army and Joint Forces.

Adversaries, regardless of their resources, are finding ways to present us with multiple tactical dilemmas. They are combining capabilities with new concepts and doctrine, as evidenced by Russia’s New Generation Warfare; China’s active defensive and local wars under “informationized” conditions; Iran’s focus on information operations, asymmetric warfare and anti-access/area denial; North Korea’s combination of conventional, information operations, asymmetric, and strategic capabilities;

Adversaries, regardless of their resources, are finding ways to present us with multiple tactical dilemmas. They are combining capabilities with new concepts and doctrine, as evidenced by Russia’s New Generation Warfare; China’s active defensive and local wars under “informationized” conditions; Iran’s focus on information operations, asymmetric warfare and anti-access/area denial; North Korea’s combination of conventional, information operations, asymmetric, and strategic capabilities;  ISIS’s often improvised yet complex capabilities employed during the Battle of Mosul, in Syria, and elsewhere; and the proliferation of anti-armor capabilities seen in Yemen, Iraq, and Syria, as well as the use of ballistic missiles by state and non-state actors.

ISIS’s often improvised yet complex capabilities employed during the Battle of Mosul, in Syria, and elsewhere; and the proliferation of anti-armor capabilities seen in Yemen, Iraq, and Syria, as well as the use of ballistic missiles by state and non-state actors.

Our adversaries have excelled at Prototype Warfare, using new improvised capabilities that converge technologies and COTS systems—in some cases for specific attacks—to great effect. ISIS, for example, has used commercial drones fitted with 40mm grenades to attack US and allied forces near Mosul, Iraq and Raqaa, Syria.  While these attacks caused little damage, a Russian drone dropping a thermite grenade caused the destruction of a Ukrainian arms depot at Balakleya, which resulted in massive explosions and fires, the evacuation of 23,000 citizens, and $1 billion worth of damage and lost ordnance.

While these attacks caused little damage, a Russian drone dropping a thermite grenade caused the destruction of a Ukrainian arms depot at Balakleya, which resulted in massive explosions and fires, the evacuation of 23,000 citizens, and $1 billion worth of damage and lost ordnance.

Additionally, our adversaries continue to make strides in developing Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear (CBRN) capabilities. We must, at a tactical level, be prepared to operate in a CBRN environment.

Operational Lessons Learned:

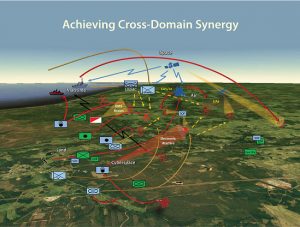

Operational lessons learned are teaching us that our traditional—and heretofore very successful—ways of waging warfare will not be enough to ensure victory on future battlefields.  Commanders must now sequence battles and engagements beyond the traditional land, sea, and air domains, and seamlessly, and often simultaneously, orchestrate combat effects across multi-domains, to include space and cyberspace. The multiple tactical dilemmas that our adversaries present us with create operational level challenges. Adversaries are building increasingly sophisticated anti-access/area denial “bubbles” we have to break; extending the scope of operations through the use of cyber, space, and asymmetric activities; and are utilizing sophisticated, and often deniable, methods of using information operations, often enabled by cyber capabilities, to directly target the Homeland and impact our individual and national will to fight. This simultaneous targeting of individuals and segments of populations has been addressed in our Personalized Warfare post.

Commanders must now sequence battles and engagements beyond the traditional land, sea, and air domains, and seamlessly, and often simultaneously, orchestrate combat effects across multi-domains, to include space and cyberspace. The multiple tactical dilemmas that our adversaries present us with create operational level challenges. Adversaries are building increasingly sophisticated anti-access/area denial “bubbles” we have to break; extending the scope of operations through the use of cyber, space, and asymmetric activities; and are utilizing sophisticated, and often deniable, methods of using information operations, often enabled by cyber capabilities, to directly target the Homeland and impact our individual and national will to fight. This simultaneous targeting of individuals and segments of populations has been addressed in our Personalized Warfare post.

We will have to operationalize Multi-Domain Battle to achieve victory over peer or near-peer competitors. Additionally, we must plan and be prepared to integrate other government entities and allies into our operations. The dynamism of the future OE is driven by the ever increasing volumes of information; when coupled with sophisticated whole-of-government approaches, information operations — backed by new capabilities with increasing ranges — challenge our national approach to warfare. The importance of information operations will continue, and may become the primary focus of warfare/competition in the future.

We will have to operationalize Multi-Domain Battle to achieve victory over peer or near-peer competitors. Additionally, we must plan and be prepared to integrate other government entities and allies into our operations. The dynamism of the future OE is driven by the ever increasing volumes of information; when coupled with sophisticated whole-of-government approaches, information operations — backed by new capabilities with increasing ranges — challenge our national approach to warfare. The importance of information operations will continue, and may become the primary focus of warfare/competition in the future.

When adversaries have a centralized leadership that can send a unified message and more readily adopt a whole-of-government approach, the US needs mechanisms to more effectively coordinate and collaborate among whole-of-government partners. Operations short of war may require the Department of Defense to subordinate itself to other Agencies, depending on the objective. Our adversaries’ asymmetric strategies blur the lines between war and competition, and operate in a gray zone between war and peace below the perceived threshold of US military reaction.

When adversaries have a centralized leadership that can send a unified message and more readily adopt a whole-of-government approach, the US needs mechanisms to more effectively coordinate and collaborate among whole-of-government partners. Operations short of war may require the Department of Defense to subordinate itself to other Agencies, depending on the objective. Our adversaries’ asymmetric strategies blur the lines between war and competition, and operate in a gray zone between war and peace below the perceived threshold of US military reaction.

Strategic Lessons Learned:

Strategic lessons learned demonstrate the OE will be more challenging and dynamic then in the past. A robust Homeland defense strategy will be imperative for competition from now to 2050. North Korea’s strategic nuclear capability, if able to range beyond the Pacific theater to CONUS, places a renewed focus on weapons of mass destruction and missile defense. A broader array of nuclear and weapons of mass destruction-armed adversaries will compel us to re-imagine operations in a CBRN environment, and to devise and consider new approaches to deterrence and collective security. Our understanding of deterrence and coercion theory will be different from the lessons of the Cold War.

A broader array of nuclear and weapons of mass destruction-armed adversaries will compel us to re-imagine operations in a CBRN environment, and to devise and consider new approaches to deterrence and collective security. Our understanding of deterrence and coercion theory will be different from the lessons of the Cold War.

The Homeland will be an active theater in any future conflict and adversaries will have a host of kinetic and non-kinetic attack options from our home stations all the way to the combat zone. The battlefield of the future will become far more lethal and destructive, and be contested from home station to the Joint Operational Area, requiring ways to sustain operations, and also to rapidly reconstitute combat losses of personnel and equipment. The Army requires resilient smart installations capable of not only training, equipping, preparing, and caring for Soldiers, civilians, and families, but also efficiently and capably serving as the first point of power projection and to provide reach back capabilities.

The Homeland will be an active theater in any future conflict and adversaries will have a host of kinetic and non-kinetic attack options from our home stations all the way to the combat zone. The battlefield of the future will become far more lethal and destructive, and be contested from home station to the Joint Operational Area, requiring ways to sustain operations, and also to rapidly reconstitute combat losses of personnel and equipment. The Army requires resilient smart installations capable of not only training, equipping, preparing, and caring for Soldiers, civilians, and families, but also efficiently and capably serving as the first point of power projection and to provide reach back capabilities.

Trends in demographics and climate change mean we will have to operate in areas we might have avoided in the past. These areas include cities and megacities, or whole new theaters, such as the Arctic.

Trends in demographics and climate change mean we will have to operate in areas we might have avoided in the past. These areas include cities and megacities, or whole new theaters, such as the Arctic.

Personalized warfare will increase over time, specifically targeting the brain, genomes, cultural and societal groups, individuals’ personal interests/lives, and familial ties.

Personalized warfare will increase over time, specifically targeting the brain, genomes, cultural and societal groups, individuals’ personal interests/lives, and familial ties.

Future conflicts will be characterized by AI vs AI (i.e., algorithm vs algorithm). How AI is structured and integrated will be the strategic advantage, with the decisive edge accruing to the side with more autonomous decision-action concurrency on the “Hyperactive Battlefield.” Due to the increasingly interconnected Internet of Everything and the proliferation of weapons with highly destructive capabilities to lower echelons, tactical actions will have strategic implications, putting even more strain and time-truncation on decision-making at all levels. Cognitive biases can shape our actions despite unprecedented access to information.

Future conflicts will be characterized by AI vs AI (i.e., algorithm vs algorithm). How AI is structured and integrated will be the strategic advantage, with the decisive edge accruing to the side with more autonomous decision-action concurrency on the “Hyperactive Battlefield.” Due to the increasingly interconnected Internet of Everything and the proliferation of weapons with highly destructive capabilities to lower echelons, tactical actions will have strategic implications, putting even more strain and time-truncation on decision-making at all levels. Cognitive biases can shape our actions despite unprecedented access to information.

The future OE presents us with a combination of new technologies and societal changes that will intensify long-standing international rivalries, create new security dynamics, and foster instability as well as opportunities. The Army recognizes the importance of this moment  and is engaged in a modernization effort that rivals the intellectual momentum following the 1973 Starry Report and the resultant changes the “big five” (i.e., M1 Abrams Tank, M2 Bradley Fighting Vehicle, AH-64 Apache Attack Helicopter, UH-60 Black Hawk Utility Helicopter, and Patriot Air Defense System) wrought across leadership development and education, concept, and doctrine development that provided the U.S. Army overmatch into the new millennium.

and is engaged in a modernization effort that rivals the intellectual momentum following the 1973 Starry Report and the resultant changes the “big five” (i.e., M1 Abrams Tank, M2 Bradley Fighting Vehicle, AH-64 Apache Attack Helicopter, UH-60 Black Hawk Utility Helicopter, and Patriot Air Defense System) wrought across leadership development and education, concept, and doctrine development that provided the U.S. Army overmatch into the new millennium.

Based on the future OE, the Army’s leadership is asking the following important questions:

• What type of force do we need?

• What capabilities will it require?

• How will we prepare our Soldiers, civilians, and leaders to operate within this future?

Clearly the OE is the starting point for this entire process.

For additional information regarding the Future OE, please see the following:

Technology and the Future of War podcast, hosted by the Modern War Institute at the U.S. Military Academy in West Point, New York.

An Advanced Engagement Battlespace: Tactical, Operational and Strategic Implications for the Future Operational Environment, posted on Small Wars Journal.

OEWatch, an monthly on-line, open source journal, published by the TRADOC G-2’s Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO).

Ian Sullivan is the Assistant G-2, ISR and Futures, at Headquarters, TRADOC.