[Editor’s Note: The U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) recruits, trains, educates, develops, and builds the Army, driving constant improvement and change to ensure that the Army can successfully compete and deter, fight, and decisively win on any battlefield. The pace of change, however, is accelerating with the convergence of new and emergent technologies that are driving the changing character of warfare in the future Operational Environment (OE). Preparing to compete and win in this future OE is one of the toughest challenges facing the Army. TRADOC must identify  the requisite new Knowledge, Skills, and Behaviors (KSBs) that our Soldiers and leaders will need to compete and win, and then program and implement the associated policy changes, improvements to training facilities, development of leader programs, and the integration of required equipment into the Multi-Domain force.]

the requisite new Knowledge, Skills, and Behaviors (KSBs) that our Soldiers and leaders will need to compete and win, and then program and implement the associated policy changes, improvements to training facilities, development of leader programs, and the integration of required equipment into the Multi-Domain force.]

The future OE will compel a change in the character of warfare driven by the diffusion of power, economic disparity, and the democratization and convergence of technology. There are no longer defined transitions from peace to war, or from competition to conflict. “Steady State” now consists of continuous, dynamic, and simultaneous competition and conflict that is not necessarily cyclical. Russia and China, our near-peer competitors, confront us globally, converging

The future OE will compel a change in the character of warfare driven by the diffusion of power, economic disparity, and the democratization and convergence of technology. There are no longer defined transitions from peace to war, or from competition to conflict. “Steady State” now consists of continuous, dynamic, and simultaneous competition and conflict that is not necessarily cyclical. Russia and China, our near-peer competitors, confront us globally, converging  capabilities with hybrid strategies to expand the battlefield across all domains and create hemispheric threats challenging us from home stations to the Close Area. They seek to achieve national objectives through competition short of conflict and synthesize emerging technologies with military doctrine and operations to deploy capabilities that create multiple layers of multi-domain stand-off. Additionally, regional competitors and non-state actors such as Iran, North Korea, and regional and transnational terrorist organizations, will effectively compete and fight in similar ways shaped to their strategic situations, but with lesser scope and scale in terms of capabilities.

capabilities with hybrid strategies to expand the battlefield across all domains and create hemispheric threats challenging us from home stations to the Close Area. They seek to achieve national objectives through competition short of conflict and synthesize emerging technologies with military doctrine and operations to deploy capabilities that create multiple layers of multi-domain stand-off. Additionally, regional competitors and non-state actors such as Iran, North Korea, and regional and transnational terrorist organizations, will effectively compete and fight in similar ways shaped to their strategic situations, but with lesser scope and scale in terms of capabilities.

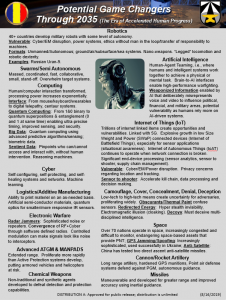

The convergence and availability of cutting-edge technologies will act as enablers and force multipliers for our adversaries. Artificial intelligence (AI), quantum information sciences, and the Internet of Things will flatten decision making structures and increase speed on the battlefield, while weaponized information

The convergence and availability of cutting-edge technologies will act as enablers and force multipliers for our adversaries. Artificial intelligence (AI), quantum information sciences, and the Internet of Things will flatten decision making structures and increase speed on the battlefield, while weaponized information  will empower potential foes, enabling them to achieve effects at a fraction of the cost of conventional weapons, without risking armed conflict. Space will become a contested domain, as our adversaries will enhance their ability to operate in that domain while working to deny us what was once a key area of advantage.

will empower potential foes, enabling them to achieve effects at a fraction of the cost of conventional weapons, without risking armed conflict. Space will become a contested domain, as our adversaries will enhance their ability to operate in that domain while working to deny us what was once a key area of advantage.

Preparing for this new era is one of the toughest challenges the Army will face in the next 25 years. A key component of this preparation is identifying the skills and attributes required for the Soldiers and Leaders operating in our multi-domain formations.

The U.S. Army currently has more than 150 Military Occupational Specialties (MOSs), each requiring a Soldier to learn unique tasks, skills, and knowledge. The emergence of a number of new technologies – drones, AI autonomy, immersive mixed reality, big data storage and analytics, etc. – coupled with the changing character of warfare means that many of these MOSs will need to change, while new ones will need to be created. This already has been seen in the wider U.S. and global economy, where the growth of internet services, smartphones, social media, and cloud technology over the last ten years has introduced a host of new occupations that previously did not exist.

– drones, AI autonomy, immersive mixed reality, big data storage and analytics, etc. – coupled with the changing character of warfare means that many of these MOSs will need to change, while new ones will need to be created. This already has been seen in the wider U.S. and global economy, where the growth of internet services, smartphones, social media, and cloud technology over the last ten years has introduced a host of new occupations that previously did not exist.

Acquiring and developing the talent pool and skills for a new MOS requires policy changes, improvements to training facilities, development of leader programs, and the integration of required equipment into current and planned formations.  The Army’s recent experience building a cyber MOS offers many lessons learned. The Army needed to change policies for direct entry into the force, developed cyber training infrastructure at Fort Gordon, incorporated cyber operations into live training exercises at home station and the Combat Training Centers, built the Army Cyber Institute at West Point, and developed concepts and equipment baselines for cyber protection teams. This effort required action from Department of the Army and each of the subordinate Army commands. Identifying, programming, and implementing new knowledge, skills, and attributes is a multi-year effort that requires synchronizing the delivery of Soldiers possessing the requisite skills with the fielding of a Multi-Domain Operations (MDO)-capable force in 2028 and the MDO-ready force in 2035.

The Army’s recent experience building a cyber MOS offers many lessons learned. The Army needed to change policies for direct entry into the force, developed cyber training infrastructure at Fort Gordon, incorporated cyber operations into live training exercises at home station and the Combat Training Centers, built the Army Cyber Institute at West Point, and developed concepts and equipment baselines for cyber protection teams. This effort required action from Department of the Army and each of the subordinate Army commands. Identifying, programming, and implementing new knowledge, skills, and attributes is a multi-year effort that requires synchronizing the delivery of Soldiers possessing the requisite skills with the fielding of a Multi-Domain Operations (MDO)-capable force in 2028 and the MDO-ready force in 2035.

The Army’s MDO concept offers a clear glimpse of the types of new skills that will be required to win on the future battlefield. A force with all warfighting functions enabled by big data and AI will require Soldiers with data science expertise and some basic coding experience to improve AI integration and to maintain proper transparency and biases supporting leader decision making. The Internet of Battle things connecting Soldiers and systems will require Soldiers with technical integration skills and cyber security experience. The increased numbers of air and land robots and associated additive manufacturing systems to support production and maintenance means a new series of maintenance skills now only found in manufacturing centers, Amazon warehouses, and universities. There are many more emerging skill requirements. Not all of these will require a new MOS, but in some cases, the introduction of new skill identifiers and functional areas may be required.

The Army’s MDO concept offers a clear glimpse of the types of new skills that will be required to win on the future battlefield. A force with all warfighting functions enabled by big data and AI will require Soldiers with data science expertise and some basic coding experience to improve AI integration and to maintain proper transparency and biases supporting leader decision making. The Internet of Battle things connecting Soldiers and systems will require Soldiers with technical integration skills and cyber security experience. The increased numbers of air and land robots and associated additive manufacturing systems to support production and maintenance means a new series of maintenance skills now only found in manufacturing centers, Amazon warehouses, and universities. There are many more emerging skill requirements. Not all of these will require a new MOS, but in some cases, the introduction of new skill identifiers and functional areas may be required.

Some of the needed skills may be inherent within the next generation(s) of recruits. Many of the games, drones, and other everyday technologies that  already are, or soon will be very common – narrow AI, app development and general programming, and smart devices – will yield a variety of intrinsic skills that recruits will have prior to entering the Army. Just like we no longer train Soldiers on how to use a computer, games like Fortnite©, with no formal relationship with the military, will provide players with militarily-useful skills such as communications, problem solving, and creative thinking, all while attempting to survive against persistent attack. Due to these trends, recruits may come into the Army with fundamental technical skills and baseline military thinking attributes that flatten the learning curve for Initial Entry Training (IET).

already are, or soon will be very common – narrow AI, app development and general programming, and smart devices – will yield a variety of intrinsic skills that recruits will have prior to entering the Army. Just like we no longer train Soldiers on how to use a computer, games like Fortnite©, with no formal relationship with the military, will provide players with militarily-useful skills such as communications, problem solving, and creative thinking, all while attempting to survive against persistent attack. Due to these trends, recruits may come into the Army with fundamental technical skills and baseline military thinking attributes that flatten the learning curve for Initial Entry Training (IET).

While these new recruits may have a set of some required skills, there will still be a premium placed on premier skillsets in fields such as AI and machine learning, robotics, big data management, and quantum information sciences. Due to the high demand for these skillsets, the Army will have to compete for talent with private industry, battling them on compensation, benefits, perks, and a less restrictive work environment. In light of this, the Army may have to consider adjusting or relaxing its current recruitment processes, business practices, and force structuring to ensure it is able to attract and retain expertise. It also may have to reconsider how it adapts and utilizes its civilian workforce to undertake these types of tasks in new and creative ways.

If you enjoyed reading this, please see the following MadSci blog posts:

… and the Mad Scientist Learning in 2050 Conference Final Report.

I couldn’t agree more with the argument in this article. The Army is not prepared for the onslaught of data that will be available from sensors in future conflicts. Soldiers must be fluent in consuming, analyzing, and communicating the results from large data sets to drive decisions and maintain the advantage. The Army currently relies on a very small community of analytic professionals, such as ORSAs, and contractors to provide this capability but must expand this skill set to the broader force. This is why I propose the Army create two ASIs to train Soldier across all ranks and positions: Full-Stack Data Scientists and Analytic Translators. Full Stack Data Scientist provide an end-to-end analytic capability from the data source to the algorithm development and ending with the data visualization. While Analytic Translators serve as the conduit between the technical talent and the Commander. They provide ‘the art of the possible’ and communicate technical constraints and capabilities within the operational environment.

I’d be happy to discuss in further detail and get your perspective!