[Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist Laboratory is pleased to publish our latest “Tenth Man” post. This Devil’s Advocate or contrarian approach serves as a form of alternative analysis and is a check against group think and mirror imaging. We offer it as a platform for the contrarians in our network to share their alternative perspectives and analyses regarding the Operational Environment (OE). Today’s post examines a foundational assumption about the Future Force by challenging it, reviewing the associated implications, and identifying potential signals and/or indicators of change. Read on!]

Assumption: The United States will maintain sufficient Defense spending as a percentage of its GDP to modernize the Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) force. [Related MDO Baseline Assumption – “b. The Army will adjust to fiscal constraints and have resources sufficient to preserve the balance of readiness, force structure, and modernization necessary to meet the demands of the national defense strategy in the mid-to far-term (2020-2040),” TRADOC Pam 525-3-1, The U.S. Army in Multi-Domain Operations 2028, p. A-1.]

Assumption: The United States will maintain sufficient Defense spending as a percentage of its GDP to modernize the Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) force. [Related MDO Baseline Assumption – “b. The Army will adjust to fiscal constraints and have resources sufficient to preserve the balance of readiness, force structure, and modernization necessary to meet the demands of the national defense strategy in the mid-to far-term (2020-2040),” TRADOC Pam 525-3-1, The U.S. Army in Multi-Domain Operations 2028, p. A-1.]

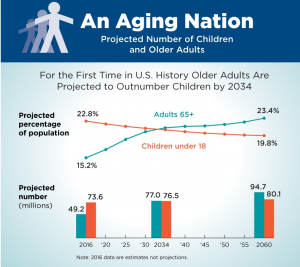

Over the past decades, the defense budget has varied but remained sufficient to accomplish the missions of the U.S. military. However, a graying population with fewer workers and longer life spans will put new demands on the non-discretionary and discretionary federal budget. These stressors on the federal budget may indicate that the U.S. is following the same path as Europe and Japan. By 2038, it is projected that 21% of Americans will be 65 years old or older.1 Budget demand tied to an aging population will threaten planned DoD funding levels.

In the near-term (2019-2023), total costs in 2019 dollars are projected to remain the same. In recent years, the DoD underestimated the costs of acquiring weapons systems and maintaining compensation levels. By taking these factors into account, a 3% increase from the FY 2019 DoD budget is needed in this  timeframe. Similarly, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that costs will steadily climb after 2023. Their base budget in 2033 is projected to be approximately $735 billion — that is an 11% increase over ten years. This is due to rising compensation rates, growing costs of operations and maintenance, and the purchasing of new weapons systems.2 These budgetary pressures are connected to several stated and hidden assumptions:

timeframe. Similarly, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that costs will steadily climb after 2023. Their base budget in 2033 is projected to be approximately $735 billion — that is an 11% increase over ten years. This is due to rising compensation rates, growing costs of operations and maintenance, and the purchasing of new weapons systems.2 These budgetary pressures are connected to several stated and hidden assumptions:

-

- An all-volunteer force will remain viable [Related MDO Baseline Assumption – “a. The U.S. Army will remain a professional, all volunteer force, relying on all components of the Army to meet future commitments.”],

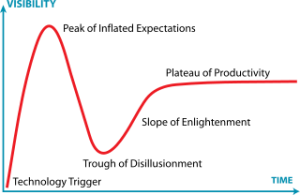

- Materiel solutions’ associated technologies will have matured to the requisite Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs), and

- The U.S. will have the industrial ability to reconstitute the MDO force following “America’s First Battle.”

Implications: If these assumptions prove false, the manned and equipped force of the future will look significantly different than the envisioned MDO force. A smaller DoD budget could mean a small fielded Army with equipping  decisions for less exquisite weapons systems. A smaller active force might also drive changes to Multi-Domain Operations and how the Army describes the way it will fight in the future.

decisions for less exquisite weapons systems. A smaller active force might also drive changes to Multi-Domain Operations and how the Army describes the way it will fight in the future.

Signpost / Indicators of Change:

-

- 2008-type “Great Recession”

- Return of budget control and sequestration

- Increased domestic funding for:

- Universal Healthcare

- Universal College

- Social Security Fix

- Change in International Monetary Environment (higher interest rates for borrowing)

If you enjoyed this alternative view on force modernization, please also see the following posts:

-

- Jomini’s Revenge: Mass Strikes Back! by Zachery Tyson Brown

-

- The Myth of Agincourt and Lessons on Army Modernization, by Ian Sullivan

- Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

1 “The long-term impact of aging on the federal budget,” by Louise Sheiner, Brookings, 11 January 2018 https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-long-term-impact-of-aging-on-the-federal-budget/

2 “Long-Term Implications of the 2019 Future Years Defense Program,” Congressional Budget Office, 13 February 2019. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/54948

mirror imaging. The Mad Scientist Laboratory offers it as a platform for the contrarians in our network to share their alternative perspectives and analyses regarding the Operational Environment (OE). We continue our series of “Tenth Man” posts examining the foundational assumptions of

mirror imaging. The Mad Scientist Laboratory offers it as a platform for the contrarians in our network to share their alternative perspectives and analyses regarding the Operational Environment (OE). We continue our series of “Tenth Man” posts examining the foundational assumptions of The character of warfare will change in the future OE as it inexorably has since the advent of flint hand axes; iron blades; stirrups; longbows; gunpowder; breech loading, rifled, and automatic guns; mechanized armor; precision-guided munitions; and the Internet of Things. Speed, automation, extended ranges,

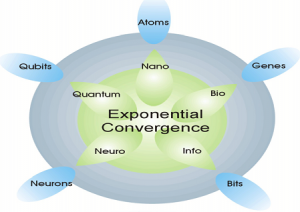

The character of warfare will change in the future OE as it inexorably has since the advent of flint hand axes; iron blades; stirrups; longbows; gunpowder; breech loading, rifled, and automatic guns; mechanized armor; precision-guided munitions; and the Internet of Things. Speed, automation, extended ranges,  broad and narrow weapons effects, and increasingly integrated multi-domain conduct, in addition to the complexity of the terrain and social structures in which it occurs, will make mid Twenty-first Century warfare both familiar and utterly alien.

broad and narrow weapons effects, and increasingly integrated multi-domain conduct, in addition to the complexity of the terrain and social structures in which it occurs, will make mid Twenty-first Century warfare both familiar and utterly alien. assumes that humans will remain central to the rationale for war and its most essential elements of execution. The nature of war has remained relatively constant from Thucydides through Clausewitz, and forward to the present. War is still waged because of fear, honor, and interest, and remains an expression of politics by other means. While machines are becoming ever more prevalent across the battlefield – C5ISR, maneuver, and logistics – we cling to the belief that parties will still go to war over human interests; that war will be decided, executed, and controlled by humans.

assumes that humans will remain central to the rationale for war and its most essential elements of execution. The nature of war has remained relatively constant from Thucydides through Clausewitz, and forward to the present. War is still waged because of fear, honor, and interest, and remains an expression of politics by other means. While machines are becoming ever more prevalent across the battlefield – C5ISR, maneuver, and logistics – we cling to the belief that parties will still go to war over human interests; that war will be decided, executed, and controlled by humans. Imagine that a machine recognizes a strategic opportunity or impetus to engage a nation-state actor that is conventionally (read that humanly) viewed as weak or in a presumed disadvantaged state. The machine launches offensive operations to achieve a favorable outcome or objective that it deemed too advantageous to pass up.

Imagine that a machine recognizes a strategic opportunity or impetus to engage a nation-state actor that is conventionally (read that humanly) viewed as weak or in a presumed disadvantaged state. The machine launches offensive operations to achieve a favorable outcome or objective that it deemed too advantageous to pass up. influence may not be conducive to victory. Victory may be simply a calculated or algorithmic outcome that causes an adversary’s machine to decide their own victory is unattainable.

influence may not be conducive to victory. Victory may be simply a calculated or algorithmic outcome that causes an adversary’s machine to decide their own victory is unattainable. – How much and how should the Army recruit and cultivate human talent if war is no longer human-centric?

– How much and how should the Army recruit and cultivate human talent if war is no longer human-centric? – Should the U.S. military divest from platforms and materiel solutions (hardware) and re-focus on becoming algorithmically and digitally-centric (software)?

– Should the U.S. military divest from platforms and materiel solutions (hardware) and re-focus on becoming algorithmically and digitally-centric (software)? – Technology advances to the point of near or actual machine sentience, with commensurate machine speed accelerating the potential for escalated competition and armed conflict beyond transparency and human comprehension.

– Technology advances to the point of near or actual machine sentience, with commensurate machine speed accelerating the potential for escalated competition and armed conflict beyond transparency and human comprehension. – Smaller, less-capable states or actors begin achieving surprising or unexpected victories in warfare.

– Smaller, less-capable states or actors begin achieving surprising or unexpected victories in warfare.

Our foundational assumption about the Future Operational Environment is that the Character of Warfare is

Our foundational assumption about the Future Operational Environment is that the Character of Warfare is

4. Coalition Warfare: A technology-enabled force will exasperate interoperability challenges with both our traditional and new allies. Our Army will not fight unilaterally on future battlefields. We have had difficulties with the interoperability of communications and have had gaps between capabilities that increased mission risks. These risks were offset by the skills our allies brought to the battlefield. We cannot build an Army that does not account for a coalition battlefield and our

4. Coalition Warfare: A technology-enabled force will exasperate interoperability challenges with both our traditional and new allies. Our Army will not fight unilaterally on future battlefields. We have had difficulties with the interoperability of communications and have had gaps between capabilities that increased mission risks. These risks were offset by the skills our allies brought to the battlefield. We cannot build an Army that does not account for a coalition battlefield and our