[Editor’s Note: Lest our readers think Army Mad Scientist is now pandering to the steamy novel set, today’s blog post by returning guest blogger Dr. Robert E. Smith, Science and Technology Advisor to USARPAC, explores the vital role “gray zone,” i.e., non-lethal, activities now play in the Operational Environment.

According to DoD Directive 3000.03E, DoD Executive Agent for Non-Lethal Weapons (NLW), and NLW Policy, the Department of Defense defines non-lethal weapons as weapons, devices, and munitions that are explicitly  designed and primarily employed to incapacitate targeted personnel or materiel immediately, while minimizing fatalities, permanent injury to personnel, and undesired damage to property in the target area or environment. Non-lethal weapons are intended to have reversible effects on personnel and materiel. The Joint Immediate Force Capabilities Office (JIFCO) oversees the Department of Defense Non-Lethal Weapons Program.

designed and primarily employed to incapacitate targeted personnel or materiel immediately, while minimizing fatalities, permanent injury to personnel, and undesired damage to property in the target area or environment. Non-lethal weapons are intended to have reversible effects on personnel and materiel. The Joint Immediate Force Capabilities Office (JIFCO) oversees the Department of Defense Non-Lethal Weapons Program.

To date, we’ve seen this competition space dominated by our adversaries. In today’s Fictional Intelligence (FICINT) submission, Dr. Smith explores how seizing the non-lethal “high ground” could effectively thwart our adversaries’ aggressive behaviors, with Taiwan resiliently asserting itself in response to China’s bullying tactics in the South China Sea — all without firing a shot! The U.S. Army (and especially its Transportation Corps’ fleet of watercraft) should take note — not every problem presented in the Operational Environment is a “nail” requiring lethal blows from a “hammer” — Read on!]

Chapter 1: Shades of Gray – The Coast Guard Standoff

Taiwan Coast Guard Vessel “Resolute”

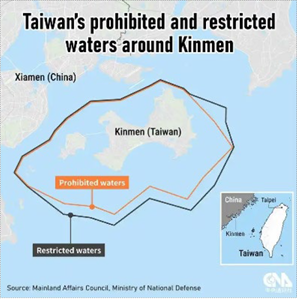

Captain Lin Wei stood resolutely on the bridge of the Taiwan Coast Guard vessel “Resolute,” his eyes scanning the choppy waters around the Kinmen Islands. The wind whipped his face, bringing the salty tang of the Taiwan Strait, and the tension in the air was palpable. Reports had come in of two Chinese Coast Guard ships deploying floating barriers into the restricted waters surrounding Kinmen, a territory hotly contested by Taiwan and China. His orders were crystal clear: deter their advance without escalating to lethal force.

Captain Lin Wei stood resolutely on the bridge of the Taiwan Coast Guard vessel “Resolute,” his eyes scanning the choppy waters around the Kinmen Islands. The wind whipped his face, bringing the salty tang of the Taiwan Strait, and the tension in the air was palpable. Reports had come in of two Chinese Coast Guard ships deploying floating barriers into the restricted waters surrounding Kinmen, a territory hotly contested by Taiwan and China. His orders were crystal clear: deter their advance without escalating to lethal force.

Wei had family who were fishermen, and he knew China had a regular habit of trying to redraw exclusive economic zones by disrupting fishing boats using floating barriers. The barriers would entangle fishing boats’ propellers or just catch hulls. The PRC coast guard liked to wait until there were many fishermen in an area typically around fertile shoals, and then box them in. Rarely was there a loss of life. It was essentially gray-terror where effective fear could be achieved without shedding blood.

Observing the Philippine Coast Guard endure relentless Chinese water cannon assaults and dangerous maneuvers had steeled Taiwan’s resolve to adapt. Captain Lin Wei, with his neatly cropped hair already flecked with gray from years of service, felt a knot of anxiety tighten in his stomach. These brand-new, untested non-lethal technologies were his arsenal today. Each maneuver was a calculated response to years of observation and Taiwan’s own engagements with China. Now, facing two Chinese ships, he felt like as an egg trying to strike a rock. This was bolstered by China having tried some new innovations last week — dumping large numbers of used fishing nets around the shoals in the Philippines. The cleanup was more annoying than floating barrier removals. Wei pondered if the goal was controlling fishing resources, but his mind leaned towards China just being arrogant bullies.

The constant centerline crossings or harassing of Taiwan’s waters was a probing test of Taiwan’s resolve and readiness. With the United States far away, Taiwan needed to deter these incremental encroachments to gain early warnings of potential invasion – especially for the outlying islands which only a mile from mainland China. The “Resolute” had been upgraded with state-of-the-art technologies, but Lin couldn’t shake the fear of waking a giant with these unproven tools. His jaw tightened, and his voice, though steady, carried an underlying tension.

As the Chinese vessels loomed closer, their gray hulls cutting through the waves with ominous precision, Wei signaled for the ship’s UAS (Unmanned Aerial System) to take flight. The small drone buzzed into the air, its rotors humming softly against the backdrop of the sea’s roar. The megaphone on the drone crackled to life. “Attention, Chinese Coast Guard vessels. You are violating Taiwan’s territory. Turn back immediately,” it blared, the command echoing across the water.

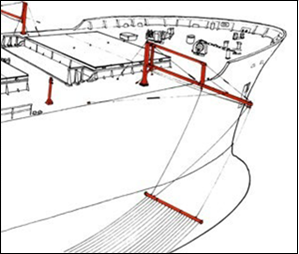

“Activate the P-trap device,” Lin ordered.

The P-trap (Propeller Trap) system was ingeniously simple in its design. The “Resolute” deployed arms on both sides, releasing multiple trailing cables into the water. These cables were designed to entangle the propellers of any approaching vessel, preventing them from getting too close. The lines were virtually invisible to the naked eye since they floated just below the surface, but they were extremely effective. Wei had seen a demonstration of the system in calm waters; now it was time to see it in action under pressure.

The Resolute’s capabilities, though impressive, were not entirely state-of-the-art. The United States had been hesitant to transfer its most advanced technology, fearing sensitive information might leak to China. Wei knew about the U.S. Joint Intermediate Force Capabilities Office (JIFCO) and their cutting-edge developments, like the Active Denial System, which used millimeter waves to induce an intense burning sensation on targets. JIFCO had also pioneered electronic warfare technologies capable of disabling engines and electronics on ships and vehicles. These were powerful tools, but ones that had not been shared with Taiwan.

Wei’s feelings were a mix of gratitude and frustration. The lack of complete trust from the U.S. stung, but he was also deeply appreciative of the support they did provide. He longed for the U.S. to abandon its policy of strategic ambiguity and offer more direct backing. As he watched the Chinese ships approach, their presence a stark reminder of the ever-present threat, he pushed these thoughts aside. His focus was on the task at hand.

Chinese Coast Guard Vessel “Haijing 5203”

Captain Zhang Liang stood on the bridge of the “Haijing 5203,” his gaze drifting over the Taiwanese cutter ahead. The salty sea air filled his lungs as he gripped the railing, a practiced calm masking the underlying tension of China’s strict oversight. His demeanor was almost bored; these standoffs had become routine. Harassing fishing vessels was easier, though the Taiwan Coast Guard was always more stubborn. So far, no ships had ever been sunk.

The Taiwanese drone buzzed overhead, its warnings growing more insistent. Liang flicked his wrist dismissively, as if swatting a fly. “Ignore the warning,” he said, his tone flat. “Continue our approach.”

The Chinese vessels pressed forward, unfazed by the drone. Zhang’s face remained a mask of indifference, but his eyes briefly flashed with irritation as the drone persisted. He smoothed it away, focusing on his role—China was the rightful authority here, and Taiwan, a mere irritant. He straightened his posture, projecting an air of unquestioned dominance.

Taiwan Coast Guard Vessel “Resolute”

Wei watched the Chinese ships maintain their course, his hands tightening around the binoculars. The tension was palpable on the bridge. “Refit the drones with payload 2,” he ordered. His crew moved swiftly, launching several drones, each armed with an unconventional payload.

The first wave of drones flew towards the Chinese ships and dropped tennis balls onto their decks. The bright yellow balls bounced harmlessly but proved the point as a visual testament to Taiwan’s resolve.

“Captain, they’re not backing off,” Lieutenant Chen reported, his voice strained. Wei nodded, his eyes narrowing. “Deploy the glue payload.”

The drones flew out again, this time spraying streams of sticky adhesive across the cameras and windows of the first Chinese ship. The glue splattered and spread, coating everything it touched, making movement treacherous and vision nearly impossible.

Chinese Coast Guard Vessel “Haijing 5203”

Liang shielded his eyes reflexively as the glue splattered across the bridge windows, obscuring his view. Frustration boiled over. “Spray those drones out of the sky!” he shouted.

The “Haijing 5203” activated its water cannon briefly, blasting a drone. Zhang’s lips curled into a smirk of satisfaction, but it was short-lived as another drone swiftly replaced the fallen one.

Taiwan Coast Guard Vessel “Resolute”

Wei watched as one of his drones was taken down. He felt a surge of determination. “Release the backup drones. Load them with payload 3 – methyl cellulose.” Normally a powder, when mixed with water methyl cellulose creates hazardous slippery, viscous solutions making deck movement nearly impossible.

The next wave of drones dropped balls of methyl cellulose onto the second Chinese vessel.

Despite these efforts, the Chinese ships kept coming. One vessel aimed to ram Wei’s ship bow- on-bow. The P-trap devices had made a side-by-side approach impossible, but an off-angle bow-on-bow collision was still a threat.

“Deploy the WHAACK system,” Wei commanded.

The WHAACK (Watercraft Hull Active Armor Collison Kit) system, inspired by reactive armor on tanks and commercial airbags, was a cutting-edge defense  mechanism developed after winning an Army xTech search prize competition. His crew quickly unrolled a lightweight Kevlar-based inflatable over the ship’s rails. At the touch of a button, the airbag inflated. Inside, titanium spikes were reoriented from a flat position by the outer surface of the airbag as it inflated to a more ominous, outward facing shape. Each spike had reactive explosives that would drive home damage into the opposing ship without damaging the friendly vessel. As the Chinese ship made contact, the spikes ripped small holes in its hull, and a payload of pepper spray was released inside the “Haijing 5203.” Wei thought, “I hope they cry all the way home.”

mechanism developed after winning an Army xTech search prize competition. His crew quickly unrolled a lightweight Kevlar-based inflatable over the ship’s rails. At the touch of a button, the airbag inflated. Inside, titanium spikes were reoriented from a flat position by the outer surface of the airbag as it inflated to a more ominous, outward facing shape. Each spike had reactive explosives that would drive home damage into the opposing ship without damaging the friendly vessel. As the Chinese ship made contact, the spikes ripped small holes in its hull, and a payload of pepper spray was released inside the “Haijing 5203.” Wei thought, “I hope they cry all the way home.”

But Wei wasn’t done. He fired a low-tech rocket equipped with spider wire into the water across the bow of the retreating “Haijing 5203.” The wire tangled around the Chinese ship’s propellers, disabling it completely.

Taiwan’s National Chung-Shan institute had created this capability using a fully 3D-printed body, a hobby store rocket motor, and SpiderWire fishing line in spiral packs with a few styrofoam fishing floats. The launcher used a simple android phone that talked to the ships navionics over Bluetooth to get weather and speed data and then used a commercial digital range finder and the phone camera to compute exactly where to launch the wire and land the rocket body.

As the Chinese ships edged closer, Wei couldn’t help but recall an incident involving Australian divers. Just a few months ago, the Chinese navy destroyer “Ningbo” had allegedly used its active sonar, injuring Australian navy divers who were clearing fishing nets from their propellers. Wei vividly remembered reading the reports: how the Ningbo had approached the Australian frigate HMAS Toowoomba despite being warned about the divers in the water, and then activated its powerful hull-mounted sonar system. The sonar pulses had caused minor injuries to the divers, leading to international condemnation of China’s unsafe and unprofessional conduct.

One Chinese ship remained. Wei knew they would try to use their water cannon since the P-trap would prevent them from getting too close. He vividly remembered the news images in Liberty Times of the aftermath of the Chinese assault on a Philippine resupply vessel. The sustained blasts from the water cannons had caused severe structural damage, bent railings, and shorn canopies. Navigation and communication equipment had been drenched and rendered inoperative, while the force of the water dislodged and washed away smaller equipment on deck. The vessel had been left crippled and vulnerable, a sobering testament to the power of those cannons.

Determined to spare the “Resolute” a similar fate, Wei steeled himself. “Activate the autonomous water cannon,” he ordered. The new system could track a designated point on a monitor to counter the Chinese water cannon no matter how the ships rolled in the waves. As the Chinese ship fired its cannon, Wei’s vessel matched it, stream for stream. The water jets collided mid-air, creating a chaotic spray that drenched the decks but left the critical equipment intact.

Wei’s vessel had a secret weapon. The nozzle on his water cannon had a sliding door and a venturi that allowed hard polymer balls to be injected into the stream. The first ball was deflected as the cannons canceled each other out, but Wei adjusted the cannon’s aim slightly. The next ball snapped off the Chinese ship’s nozzle, causing it to flood its own deck.

Wei watched as the enemy vessel struggled, its crew scrambling to regain control. The memory of the Philippine vessel’s damage fueled his resolve. He wouldn’t let the “Resolute” suffer the same fate. As the Chinese ship limped away, Wei’s heart pounded with a mix of relief and pride. They had defended their waters without resorting to lethal force, and for now, the “Resolute” remained unscathed.

Both Chinese ships were now limping away. Wei’s heart raced, each beat pounding like a drum in his chest as relief washed over him. They had defended their waters without resorting to lethal force. The crew erupted in subdued cheers, their faces reflecting the tension of the encounter and the triumph of their success.

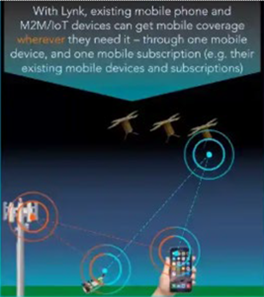

High above, filming drones captured every moment of the incident. Using Lynk’s Proliferated Low Earth Orbit (PLEO) constellation, they live- streamed the entire event across the world, showcasing Taiwan’s resolve and ingenuity in defending its sovereignty.

The Black Hornet Nano drones buzzed silently, their tiny frames blending into the sky. They captured every moment, lenses glinting in the sunlight. Data streamed from the drones to the “Resolute,” and a simple cell phone used Lynk’s “cell tower in space” constellation. Lynk allowed direct satellite-to-mobile communication, with no extra equipment needed. Real-time footage flowed seamlessly to viewers worldwide. In the past, static images or videos uploaded hours after events were not nearly as effective. They gave China time to ramp up its AI-powered propaganda machines, but live video is worth a thousand belligerent statements.

The Black Hornet Nanos, deployed at the start of the confrontation, hovered with near-silent efficiency. Measuring just 16 x 2.5 cm (6 x 1 inch) and weighing 18 grams (0.7 oz), they were practically invisible, with a flight duration of up to 25 minutes. Wei marveled at their stealth, though he wished every fishing vessel could have one despite the cost.

Chinese Coast Guard Vessel “Haijing 5203”

Captain Zhang Liang gripped the railing of his ship, frustration boiling beneath his calm exterior. The Taiwanese were proving to be more resilient and innovative than he had anticipated. His ship was coated in glue, making movement and visibility nearly impossible. The water cannon had been their best hope, but even that had been neutralized by the Taiwanese vessel’s advanced systems.

When his ship’s propellers became tangled in the spider wire, Zhang knew the mission was over. “Retreat,” he ordered through gritted teeth.

As his vessel limped away, Zhang couldn’t help but feel a grudging respect for the Taiwanese captain. This encounter had been a test of wits and technology, and today, Taiwan had won.

the island’s resistance to Chinese war games.

Liang already know that China would predictably respond with theatrical accusations. State media would claim the footage proved the US was stirring up troubles inside China with the “rogue state” Taiwan and expressed great sympathy for the families of the Chinese coast guard personnel supposedly injured in the “Taiwan attacks.” No doubt some of Liang’s crew would be asked to flood their social media with images of broken bones and cuts.

China’s rhetoric blamed Washington, insisting the video footage of the incident was fake. But the real-time footage, broadcast through Lynk made a mockery of such claims. The world’s eyes were on them, seeing the truth unfold.

If you enjoyed this post, check out the new TRADOC Pamphlet 525-92, The Operational Environment 2024-2034: Large-Scale Combat Operations — TRADOC’s informational publication defining the Operational Environment.

Explore the TRADOC G-2‘s Operational Environment Enterprise web page, brimming with information on the OE and how our adversaries fight, including:

Our China Landing Zone, full of information regarding our pacing challenge, including ATP 7-100.3, Chinese Tactics, BiteSize China weekly topics, People’s Liberation Army Ground Forces Quick Reference Guide, and our thirty-plus snapshots captured to date addressing what China is learning about the Operational Environment from Russia’s war against Ukraine (note that a DoD Common Access Card [CAC] is required to access this last link).

Our Russia Landing Zone, including the BiteSize Russia weekly topics. If you have a CAC, you’ll be especially interested in reviewing our weekly RUS-UKR Conflict Running Estimates and associated Narratives, capturing what we learned about the contemporary Russian way of war in Ukraine over the past two years and the ramifications for U.S. Army modernization across DOTMLPF-P.

Our Iran Landing Zone, including the latest Iran OE Watch articles, as well as the Iran Quick Reference Guide and the Iran Passive Defense Manual (both require a CAC to access).

Our Running Estimates SharePoint site (also requires a CAC to access), containing our monthly OE Running Estimates, associated Narratives, and the 2QFY24, 3QFY24, and 4QFY24 OE Assessment TRADOC Intelligence Posts (TIPs).

Then check out the following related Mad Scientist Laboratory gray-zone and China content:

Flash-Mob Warfare: Whispers in the Digital Sandstorm (Parts 1 and 2), by Dr. Robert E. Smith

The Most Consequential Adversaries and associated podcast, with GEN Charles A. Flynn

Volatility in the Pacific: China, Resilience, and the Human Dimension and associated podcast, with General Robert Brown (USA-Ret.)

How China Fights and associated podcast

Three Dates, Three Windows, and All of DOTMLPF-P, China and Russia: Achieving Decision Dominance and Information Advantage, and “No Option is Excluded” — Using Wargaming to Envision a Chinese Assault on Taiwan, by Ian Sullivan

China: Building Regional Hegemony and China 2049: The Flight of a Particle Board Dragon, the comprehensive report from which this post was excerpted

Competition and Conflict in the Next Decade

Disrupting the “Chinese Dream” – Eight Insights on how to win the Competition with China

Sub-threshold Maneuver and the Flanking of U.S. National Security, by Dr. Russell Glenn

Non-Kinetic War, Global Entanglement and Multi-Reality Warfare and associated podcast, with COL Stefan Banach (USA-Ret.)

Hybrid Threats and Liminal Warfare and associated podcast, with Dr. David Kilcullen

Weaponized Information: What We’ve Learned So Far…, Insights from the Mad Scientist Weaponized Information Series of Virtual Events, and all of this series’ associated content and videos [access via a non-DoD network]

Insights from Ukraine on the Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Warfare

About the Author: Dr. Robert E. Smith is the Army Futures Command International Science Advisor to U.S. Army Pacific Command. Previously he worked in the Ground Vehicles Systems Center doing research centered early synthetic prototyping and extracting tactics from gaming data. His career includes experience at Ford Motor Co., Whirlpool Corp., and General Dynamics Land Systems. He holds a Ph.D. in Mechanical Engineering from Michigan Technological University with a focus on AI and Machine Learning.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).