[Editor’s Note: As has been pointed out previously on this blog site, military culture tends to be conservative — in some instances, to the point of stultification. COL Stefan J. Banach (USA-Ret.) observed that “the value of mechanization versus the horse and the application of air power on modern battlefields during the 1919-1939 inter-war period are notable historical examples where new technological advantages were not immediately appreciated by “the experts.” Case in point — BG Hamilton S. Hawkins, an “old guard” cavalryman, who, upon retiring from active service in 1936 as the CG, 1st Cavalry Division, dedicated his time advocating resistance to mechanization in a series of editorial submissions to the Cavalry Journal in 1937 and 1938, and “insured that doctrinal and organizational change was stillborn“:

“Imagination gone wild because there is … a sheep-like rush toward mechanization and motorization without clear thinking or any apparent ability to visualize what takes place on the … battlefield, have led to a foolish and unjustified discarding of horses …

“Imagination gone wild because there is … a sheep-like rush toward mechanization and motorization without clear thinking or any apparent ability to visualize what takes place on the … battlefield, have led to a foolish and unjustified discarding of horses …

There is no sense in trying to organize a large so-called reconnaissance unit of mechanized or motorized forces.” — excerpted from BG Hawkins’ editorial entitled “Imagination Gone Wild,” in the Cavalry Journal, November-December 1938 (pp. 491-497)i

Ian Sullivan sagely pointed out in a recent post that a “learning organization requires institutional humility, an organizational open mind, and a decisive willingness to ‘disrupt yourselves before you are disrupted.‘” To put it bluntly, an effective organization must resist the tyranny of the “old guard.”

Today’s provocative blog post was a semi-finalist in our Mad Scientist Writing Contest on the 4C’s: Competition, Crisis, Conflict, and Change. LTC Christopher J. Heatherly‘s submission challenges the “old guard” in calling for a number of bold, transformative actions, including a major restructuring of the DoD, fully embracing the philosophy of Mission Command, drastically improving the Army’s deployment speed, making radical changes to the procurement cycle, and developing and implementing an enduring national military strategy. Before dismissing any of LTC Heatherly’s proposals out of hand, consider this: What price are we willing to pay to maintain the status quo, content only to implement change incrementally? Another Pearl Harbor? Or worse — ignominious defeat at the hands of an implacable adversary whose global vision holds no regard for the rules-based international order? — Read on!]

In September 1921, U.S. Army aviator Brigadier General William “Billy” Mitchell led a series of tests to determine if aircraft could sink conventional battleships under wartime conditions. Despite War Department attempts to influence the test in favor of the battleships’ supremacy, Mitchell conclusively proved the air domain was both a reality and a potentially decisive aspect of warfare. In response, U.S. Navy senior leaders attempted to scuttle the post-strike reports that ultimately found their way to the press and the American public. Far too many senior American civilian and military leaders, however, ignored the game changing impact of Mitchell’s tests until Imperial Japan forced the issue by sinking elements of the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941.

Fast forward a century later and once again the U.S. military appears slow to grasp the significance of multidomain warfare. Our competitors will employ — indeed already employ — a hybrid of kinetic and non-kinetic capabilities across all domains to achieve their goals. War in 2035 and beyond will require a Joint, whole of nation approach capable of seamlessly operating across the entire spectrum of conflict in all domains simultaneously. An additional, equally important and long overdue problem the US must confront is the lack of a coherent national strategy outlining our vital national interests, providing security assurance to our allies and deterring our enemies. Bluntly stated, the U.S. Government has not developed a lasting strategy since the end of the Cold War. Foreign policy in particular suffers radical position changes leaving the Department of Defense (DoD) uncertain regarding what is required for mission success with rapid course corrections in doctrine, training, manning, equipping, and basing.

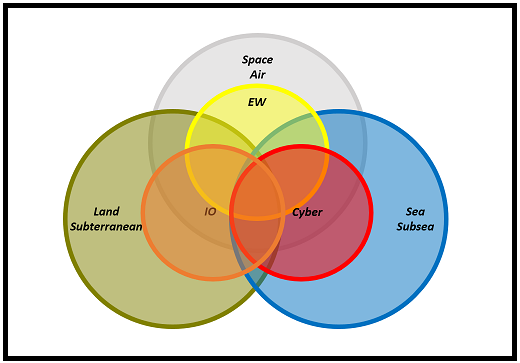

Figure 1 (below) depicts a model to visualize multidomain warfare. Within this model, the functional domains of Information Operations (IO), Cyber and Electronic Warfare (EW) are centrally located, given their ability to inordinately influence the physical domains at very low cost to the user. The domains in this model will be dynamic – e.g., the domain circles will change in size (level of activity) and location (how much a given domain influences one or more other domains). For example, cyber moves further into the land domain as a competitor brings more of their cyber capability to bear on U.S. ground forces. Meeting this challenge will require the military to restructure the DoD, fully embrace the philosophy of Mission Command, drastically improve its deployment speed, make radical changes to the procurement cycle and develop a lasting national military strategy.

Why Multidomain?

In the future, indeed in the now, the ability to wage multidomain warfare is inherently a requirement for victory. The three physical domains of sea, air, and land, and their sub-domains of subsea, space, and subterranean remain important in 2035 but control of any single physical domain will no longer guarantee victory as information and cyber supremacy will take operational precedence. Cyber and information domains will be central in military planning given their ability to influence the physical domains and mission. War will often be won before the first shot is fired or the first boot is on the ground given the snail’s pace of large-scale U.S. deployment timelines. Militaries with the best tanks, the longest-range artillery, and the fastest jets will find their capabilities irrelevant if they cannot deploy from home station, are unable to power systems up due to software viruses, or lack the legal authority granted by their national legislatures to act – all of which are influenced by, with and through IO, EW or cyber.

Functional domains have the added attraction of deniability creating further difficulty for the aggrieved party to respond. The cost, the “pay to play,” to enter the cyber and information operations domains is lower than at virtually any point in history, while the price to achieve “peer” status elsewhere via technology advantage will continue to rise, perhaps exponentially given current U.S. procurement systems. Conversely, the cost for the US to defeat low technology approaches to combat will remain inversely proportional for the foreseeable future. Commercial, off the shelf technology will deliver better capability, more efficiently, and at lower cost for our competitors.

Restructuring the Department of Defense

Service parochialism and the bureaucratic redundancy also require change in favor of a truly Joint approach to military recruitment, training, resourcing, missions, and strategy needed for multidomain warfare. Without the external forcing function of active combat or other mission deployments, the individual military services will revert to their natural state of “stove-piped” approaches  to operations. It is long past time to restructure the DoD from its current Cold War organization to meet the realities of multidomain conflict in 2035. In its present form, the military is redundant, parochial, and mired in the past. Restructuring will necessarily require the slaughtering of so-called “sacred cows,” as there is little appetite for substantial personnel strength or budget growth. [Author’s note: None of these proposals downplays the rich history and accomplishments of any branch of Service. Multidomain warfare, however, demands innovation to ensure victory in the field.]

to operations. It is long past time to restructure the DoD from its current Cold War organization to meet the realities of multidomain conflict in 2035. In its present form, the military is redundant, parochial, and mired in the past. Restructuring will necessarily require the slaughtering of so-called “sacred cows,” as there is little appetite for substantial personnel strength or budget growth. [Author’s note: None of these proposals downplays the rich history and accomplishments of any branch of Service. Multidomain warfare, however, demands innovation to ensure victory in the field.]

-

-

- Leader Development: Develop a Joint approach to missions for every service member from initial entry to their departure from the military through schooling, assignments, and operations. Incentivize Joint assignments through key development assignment designations and guidance to promotion or selection boards. Joint operations and Joint task forces should be the rule, not the exception, to military business.

-

-

-

- Land Domain: Increase the active Army to five operational corps of 15 divisions using personnel numbers regained by eliminating redundancy

across the DoD while adding organic Close Air Support (CAS) platforms to the force structure. Align one corps against each Combatant Command, with the U.S. National Guard assuming responsibility for homeland defense. Retain a smaller airborne capability, with organic lift assets, but combined with a heavy division, given the air defense threat extant in any likely theater of operations.

across the DoD while adding organic Close Air Support (CAS) platforms to the force structure. Align one corps against each Combatant Command, with the U.S. National Guard assuming responsibility for homeland defense. Retain a smaller airborne capability, with organic lift assets, but combined with a heavy division, given the air defense threat extant in any likely theater of operations.

- Land Domain: Increase the active Army to five operational corps of 15 divisions using personnel numbers regained by eliminating redundancy

-

-

-

- Land Domain, continued: The Army, which conducted more amphibious assaults than the Marines in WWII, already provides the United States Marine Corps (USMC) with logistics and training; it’s time to complete the marriage. Realign the USMC by moving its capability to the Army as a dedicated fifth amphibious corps for US INDO-PACOM but without the unnecessary overhead required of a separate service. The elimination of USMC-specific headquarters in schools, Service components, and elsewhere will allow for DoD growth in cyber, IO, and combat arms. It will also force Joint cooperation, as the Army and Navy work together.

-

-

-

- Air/Space Domain: Refocus the United States Air Force (USAF) to space, air supremacy, suppression of enemy air defense (SEAD), strategic bombing, nuclear deterrence, missiles, and transport missions. Reassign CAS to the Army via an organic and dedicated fixed wing capability. This will also create more “Jointness” as the Army and USAF share the domain.

-

-

-

- Maritime Domain. The United States Navy (USN) retains its mission set, but must develop new platforms to control the sea domain without the tremendous cost of increasingly vulnerable capital ships. The USN also maintains their current role in nuclear deterrence.

-

-

-

- Cyber, EW, and IO Domains: Fully invest in offensive and defensive capabilities across the DoD to include proactive authorities to anticipate and act before a competitor action, thereby regaining and retaining the initiative.

Additionally, integrate these capabilities full time with the warfighting units to ensure they train together before operational deployment.

Additionally, integrate these capabilities full time with the warfighting units to ensure they train together before operational deployment.

- Cyber, EW, and IO Domains: Fully invest in offensive and defensive capabilities across the DoD to include proactive authorities to anticipate and act before a competitor action, thereby regaining and retaining the initiative.

-

-

-

- Special Operations: Place control of special operations forces (SOF) under the area/theater/operational commander to ensure coordinated operations and exercises. Examine Joint / Combined SOF units for best practices and lessons learned to be implemented by the larger DoD.

-

Decentralized Command in a Connected World

The lethal and non-lethal capabilities necessary in multidomain battle will require a decentralized mission command and C5ISR structure unprecedented in military history. This will challenge the combat experience of American military officers who learned their profession in the centrally controlled Global War on Terrorism (GWOT) in Iraq or Afghanistan. Operations in those theaters had the relative luxuries of time, material resources, sanctuary bases, and leader oversight that will be non-existent by 2035, outside and potentially within the Continental United States. The DoD should  embrace mission command by empowering leaders to make decisions at their level without having to reach back to theater commanders or the Pentagon. The speed of multidomain operations will not allow the hierarchical approach used in Iraq, Afghanistan, or elsewhere and will instead require a high degree of subordinate trust and risk acceptance by senior leadership. These same leaders must understand the inherent learning curve associated with decentralized command and capability employment to resist the temptation to pull authorities back to their level. Indeed, 21st century combat will further demand a disciplined, educated, and trained force of confident professionals able to operate independently of higher headquarters for extended periods of time and willing to ignore orders from isolated command posts lacking operational context.

embrace mission command by empowering leaders to make decisions at their level without having to reach back to theater commanders or the Pentagon. The speed of multidomain operations will not allow the hierarchical approach used in Iraq, Afghanistan, or elsewhere and will instead require a high degree of subordinate trust and risk acceptance by senior leadership. These same leaders must understand the inherent learning curve associated with decentralized command and capability employment to resist the temptation to pull authorities back to their level. Indeed, 21st century combat will further demand a disciplined, educated, and trained force of confident professionals able to operate independently of higher headquarters for extended periods of time and willing to ignore orders from isolated command posts lacking operational context.

The military will require mobile command posts capable of rapid movement, setup, operations execution, and displacement to survive battle. The days of static “TOC Mahals” and secure Forward Operating Bases (FOBs) will largely be relics off the past. In 2016, then Army Chief of Staff (CSA) and now Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) General Mark Milley succinctly captured this maxim stating, “On the future battlefield, if you stay in one place longer than two or three hours, you will be dead.”1

“Firstest with the Mostest”

Across the military, all three components (e.g., Active Army, Army Reserve, and Army National Guard) must drastically reduce their mobilization timelines from the current months/weeks model to days/hours lest they arrive long after the  war is lost. Restated, the 1990 Desert Storm and 2003 Iraqi Freedom deployment models are obsolete in multidomain combat. Maintaining this level of readiness will require civilian and military leaders to focus on Mission Essential Task Lists (METL), enforcement of readiness criteria, and solving performance deficiencies at the individual or unit level. The DoD must empower unit commanders to immediately remove unfit and non-deployable personnel from their ranks.

war is lost. Restated, the 1990 Desert Storm and 2003 Iraqi Freedom deployment models are obsolete in multidomain combat. Maintaining this level of readiness will require civilian and military leaders to focus on Mission Essential Task Lists (METL), enforcement of readiness criteria, and solving performance deficiencies at the individual or unit level. The DoD must empower unit commanders to immediately remove unfit and non-deployable personnel from their ranks.

Improved Research, Development, and Fielding

As of this writing, the pace of technology development is increasing, indeed continues to increase, beyond that first envisioned by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore in 1965 when he postulated the number of transistors on a microchip would double every two years with a corresponding 50% reduction in computer prices.2 Moore’s Law, as it was later known, successfully anticipated the speed of innovation until relatively recently; we should expect further advancement to come from another venue beyond the physical microchip. Similarly, the U.S. Government, and by extension the DoD, will require a proactive, forward thinking approach to the entire research and development (R&D) cycle, replacing the current Industrial Age system.  Using the Army as an example, the “Big 5” systems of the M1 Abrams tank, M2 Bradley Fighting Vehicle, Patriot air defense system, AH-64 Apache attack helicopter, and UH-60 Blackhawk utility helicopter all harken back to the 1970s or 1980s. Attempts to field replacements, most notably through Force XXI, were unsuccessful and expensive. Acquisition regulations and laws will require wholesale revision to allow collaboration and a much faster research and development to fielding cycle. The speed of innovation demands solutions from all levels recognizing that top driven procurement priorities, while still necessary, must fully incorporate the full spectrum of initiative. Often the best solutions will come from the end users at the ground level.

Using the Army as an example, the “Big 5” systems of the M1 Abrams tank, M2 Bradley Fighting Vehicle, Patriot air defense system, AH-64 Apache attack helicopter, and UH-60 Blackhawk utility helicopter all harken back to the 1970s or 1980s. Attempts to field replacements, most notably through Force XXI, were unsuccessful and expensive. Acquisition regulations and laws will require wholesale revision to allow collaboration and a much faster research and development to fielding cycle. The speed of innovation demands solutions from all levels recognizing that top driven procurement priorities, while still necessary, must fully incorporate the full spectrum of initiative. Often the best solutions will come from the end users at the ground level.

A Realistic and Lasting National Security Strategy for the 21st Century

The US must adopt a national security strategy that accomplishes the three critical tasks of identifying our vital national interests, providing security assurance to our allies, and deterring our enemies. This strategy’s ends, ways, means, and risks should be clear to the major government agencies and the American people. Ideally, the strategy will reflect our common interests and values allowing successive administrations to retain its structure, albeit with necessary changes as the Operational Environment evolves. Security experts should consider the success and longevity of George F. Kennan’s “Long Telegram” as a model to study as they draft a strategy for this century’s challenges.

Conclusions

To paraphrase Leon Trotsky, you may not be interested in multidomain war, but multidomain war is interested in you.3 That maxim holds true today. Failure to actively study, understand, man, train, and equip for multidomain warfare all but guarantees the United States military will remain unprepared for the harsh realities of 2035 and beyond. Incremental change, via weapons platform improvements, Madison Avenue-style buzzwords, or stove-pipe approaches to new capability introduction are insufficient to meet the requirements of multidomain operations. The brave new world of 21st century conflict will require equally bold initiatives -– and the U.S. military to evolve — lest we be forced to confront the future in another Pearl Harbor moment.

If you liked this post, check out two of our other insightful entries from Mad Scientist Writing Contest on Competition, Crisis, Conflict, and Change: proclaimed Mad Scientist CPT Anjanay Kumar‘s winning entry – The U.S. Joint Force’s Defeat before Conflict; and semi-finalist 1LT Carlin Keally‘s entry – A House Divided: Microtargeting and the next Great American Threat

… as well as the following related content:

The key judgements from The Operational Environment (2021-2030): Great Power Competition, Crisis, and Conflict and its comprehensive source document

The Convergence: The Future of Ground Warfare with COL Scott Shaw, and associated podcast

Sub-threshold Maneuver and the Flanking of U.S. National Security, by Dr. Russell Glenn

The Convergence: Hybrid Threats and Liminal Warfare with Dr. David Kilcullen and associated podcast

Going on the Offensive in the Fight for the Future, and associated podcast

Top Attack: Lessons Learned from the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, and associated podcast

Mission Engineering and Prototype Warfare: Operationalizing Technology Faster to Stay Ahead of the Threat, by The Strategic Cohort at the U.S. Army Tank Automotive Research, Development, and Engineering Center (TARDEC)

“Once More unto The Breach Dear Friends”: From English Longbows to Azerbaijani Drones, Army Modernization STILL Means More than Materiel, by Ian Sullivan

Lieutenant Colonel Christopher J. Heatherly enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1994 and earned his commission via Officer Candidate School in 1997. He has held a variety of assignments in special operations, Special Forces, armored, and cavalry units. His operational experience includes deployments to Afghanistan, Iraq, South Korea, Kuwait, Mali, and Nigeria. He holds master’s degrees from the University of Oklahoma and the School of Advanced Military Studies.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

i Adaptation to Change: U.S. Army Cavalry Doctrine and Mechanization, 1938-1945, by LTC Dean A. Nowowiejski, School of Advanced Military Studies, United States Army Command and General Staff College, Ft. Leavenworth, KS, First Term A Y 94-95. See the discussion on “old guard” Cavalry senior leader resistance to mechanization — i.e., those who “insured that doctrinal and organizational change was stillborn” — on pp. 8-10 and Endnote 11 on p. 44 at: https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a300709.pdf, accessed on 7 May 2021

1 https://breakingdefense.com/2016/10/miserable-disobedient-victorious-gen-milleys-future-us-soldier/, accessed 19 February 2020

2 https://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/mooreslaw.asp, accessed 23 February 2020

3 https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/152853-you-may-not-be-interested-in-war-but-war-is, accessed 23 February 2020, Trotsky’s original quote read, “You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you.”

While I agree with most of the points raised, the folding in of the Marines into the Army is a no go, as also unfortunately would be the sensible assignment of CAS to the Army.

The Marines are arguably a special case, they are generalists who do a specialist job, while the Army are specialists that do general tasks. The difference in culture is therefore significant and not to be so easily dismissed. Though arguably, SEALs should be folded into the Army or perhaps the Marines.

The Air Force Fighter v Bomber v Transport special interest groups is what stands in the way of CAS being folded under the Army. That and the historical record of the USAAF and old wounds.

As always, these problems are part of the human condition, and as such require a more psychological approach to change to manage inter-service domain confrontation, as metaphorical cage-fights for who does what and when is what has driven the bureaucratic budget drives and the ‘iron rule’ of defend one’s ‘kingdom.’

Interesting read. Perhaps we ought to consider an even more radical approach that includes reorganizing all services under the “U.S. Defense Force” whose primary combatant elements are built around Cyber, Info Ops, and Special Ops forces. Each of these combatant element will have its own land, sea, & air/ space component that addresses Cyber/ IO/ SOF missions in a particular domain. Thoughts?

This reads to me as more-of-same. Plus up the joint, give the Army a bigger role, and move around some deck chairs.

The problem the US is facing is the same that the Roman empire faced–we are trying to maintain world-wide hegemony that we achieved during our peak while our economic and industrial superiority slowly decline and the rest of the world grows less aligned with our national interests. As happens with all bureaucracies, DOD has grown so massive and sclerotic that it cannot make meaningful change outside of a catastrophe; there are too many entrenched interests that will resist any change to the status quo, no matter what the proposed change is–the bigger the change, the more entrenched interests it will upset. As a result, every change will be a veneer on the surface which boils down to a new Deputy Assistant Secretary of something and a lot of paperwork that makes it looking like something changed, but no actual change.

The author did have some good points. We need disruption, preferably the kind we choose ourselves rather than the kind forced on us by a catastrophic failure. I think that disruption needs to be a massive down-scoping of DOD’s mandates from world-wide policing to actual defense of the United States (aka what the author seems to think the National Guard should be doing) plus a proportionate contribution to an international force (eg NATO) that addresses common interests such as freedom of navigation in international waters. This should be accompanied by a massive reduction in the size, budget, and complexity of DOD. As much as we love to talk about “agile”, the only way to be agile is to be small and unencumbered by inertia.

Let’s face it, it is not sustainable for a nation whose natural resource base and technological/industrial superiority are in decline (basically a figment of our imagination at this point) to spend more on “defense” than every other nation combined. That obviously has to end at some point, so why not downsize consciously and thoughtfully rather than waiting for a catastrophe to do it for us?

As a depiction of the relation of activities within an operational environment, Figure 1 is as misleading as Aristotle’s concept of the solar system before Copernicus. In figure 1, information operations is depicted as a separate activity within a universe of activities. This is probably because the author narrows the scope of IO to a genus of related activities like MISO, PSYOP, Public Affairs, and maybe public diplomacy. That said, IO is better understood as the ether within which the entire universe of noted activities operate. There is no activity listed in the figure that in some significant way is unrelated to and must be considered in the information environment. Information operations is the sun around which the other activities are satellites. Therefore, the figure would be much more accurate if all activities were circumscribed by a line specified as information operations.