[Editor’s Note: Regular readers of the Mad Scientist Laboratory know that we regularly explore how our sole pacing threat — China — could attempt to re-unify Taiwan with the mainland under the mantel of the Chinese Communist Party. As Ian Sullivan observed in his seminal Three Dates, Three Windows, and All of DOTMLPF-P:

“A year [and a half] ago, CIA Director William Burns stated “that the United States knew ‘as a matter of intelligence’ that Xi had ordered his military to be ready to conduct an invasion of self-governed Taiwan by 2027.” Director Burns elaborated, “Now, that does not mean that he’s decided to conduct an invasion in 2027, or any other year, but it’s a reminder of the seriousness of his focus and his ambition.”

Today’s post by returning guest blogger Dr. Stewart Bentley builds upon his previous insightful submission — Tyranny of Time & Distance: Logistics & Contested Deployment in LSCO — by weaving a compelling vignette in which China exploits and amplifies conditions (both natural and man-made) to successfully execute a “fait accompli” attack to secure their control of the island of Formosa.

The purpose of this post is not to suggest that all or any of these conditions could or would occur — rather, it is to illustrate each of the “challenges that the U.S. military could face when called upon to mobilize and deploy from a contested homeland and stage into a potentially hostile area.” Perhaps most importantly, Dr. Bentley reminds us that — as in all military operations — Mother Nature always gets a vote, and our adversaries stand ready to exploit the resulting conditions…. Read on!]

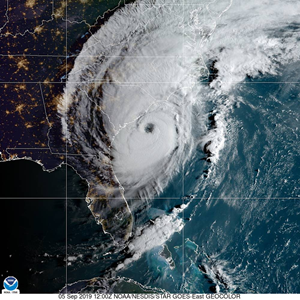

The Chinese commander of the invasion task force leaned back in his chair at the conference table, staring intently at the split screen television monitors on the wall. One monitor was streaming the weather reports about the strengthening hurricane off the American East Coast. It was expected to strengthen to a Category 4 and make landfall at Charleston in three days. In addition, it was expected to linger and only slowly make its way North along the coast. Mandatory evacuations for the South Carolina Low Country from Charleston North to Wilmington were underway. The local state governments had already implemented their reverse lane plans on the interstates — facilitating evacuation but shutting down eastbound traffic into Charleston and Wilmington. The state governors had declared states of emergency and mobilized the National Guard to respond. Port closures were already expected, significantly impacting maritime traffic.

The other monitor broadcast images of Los Angeles, where a massive earthquake had brought the city — and more importantly for the Chinese — the Port of Los Angeles to a grinding halt.

The other monitor broadcast images of Los Angeles, where a massive earthquake had brought the city — and more importantly for the Chinese — the Port of Los Angeles to a grinding halt.

A flashing “Breaking News” ribbon began to roll across the screens. A large cargo ship had lost power and slammed into the Sabine Lake causeway bridge at Port Arthur, Texas, causing a partial bridge collapse and halting maritime traffic in and out of the port facilities at Beaumont.

These simultaneous events were the pre-conditions the Chinese had been waiting and planning for. The environment would now exist to impede, but not stop, any American military response during their movement from the bases to major maritime ports. The commander turned to his intelligence chief and nodded his head. The intelligence chief picked up a phone on the conference table and punched in a number, spoke for a few minutes, and then hung up.

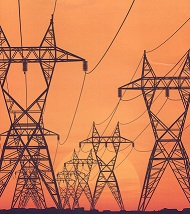

Several hours later, Western media began reporting that electrical power substations, primarily on the East Coast and in central Texas, had been seriously damaged or destroyed using some form of explosives — causing massive outages and hampering hurricane evacuation operations along the East Coast. In addition, cyber-attacks were disrupting cellular communications networks across the United States.

Several hours later, Western media began reporting that electrical power substations, primarily on the East Coast and in central Texas, had been seriously damaged or destroyed using some form of explosives — causing massive outages and hampering hurricane evacuation operations along the East Coast. In addition, cyber-attacks were disrupting cellular communications networks across the United States.

The task force commander convened a conference of his senior leaders and staff. He informed them that now that the invasion pre-conditions had been met, the operation could commence. The Americans would be seriously slowed in their mobilization and deployment from the ports of Charleston, Wilmington, Beaumont, and the Port of Los Angeles. Movement on the southeastern interstates would be hindered, potentially even halted if inland flooding approached the same levels seen during Hurricane Joaquin in 2015.

The island invasion timeline only needed 96 hours of unimpeded movement for Chinese airborne troops to conduct airfield and port seizures to establish and expand the lodgments for follow on forces and logistical support. Minimal firepower would be expended to capture the island intact and maintain its infrastructure to support gaining control of the island.

Just prior to the operation, the Chinese ambassador to the United States would hand deliver a carefully crafted letter to the American Secretary of State outlining Chinese intentions to “re-unify” China and their desire to avoid open conflict with the United States. The Chinese were counting on the rising sense of isolationism in American society and reluctance to become involved in foreign disputes with open ended commitments for unclear goals.

Following the delivery of that letter, the National Security Council convened in the White House Situation Room. After a full intelligence briefing on what was known about the People’s Liberation Army goals and intentions, the President issued a partial mobilization order to the Department of Defense. INDOPACOM was immediately designated as the combatant command for the military response.

Following the delivery of that letter, the National Security Council convened in the White House Situation Room. After a full intelligence briefing on what was known about the People’s Liberation Army goals and intentions, the President issued a partial mobilization order to the Department of Defense. INDOPACOM was immediately designated as the combatant command for the military response.

At the National Military Command Center (aka the “Tank”) in the Pentagon, several major challenges were immediately apparent to the planners in response to the impending invasion. In addition to the port closures on the East Coast and the Port Arthur causeway bridge collapse, the interstate closures on I-95, I-26, and I-40 in the Carolinas were going to seriously impede military movement from Fort Bragg to Charleston and Wilmington. The causeway bridge collapse meant that Fort Hood units would need a different port to deploy from. While the 82nd Airborne Division’s Ready Brigade could deploy via airlift within 18 hours of notification, the flow of follow-on forces was going to be seriously delayed. Further, planners at XVIII Airborne Corps headquarters were uncertain where the paratroopers would be able to land: Was it going to be on Taiwan proper? If Chinese forces held the airport in force, the All-Americans would be quickly outnumbered and overwhelmed. The southernmost Okinawan Island of Ishigaki had only a small airport. Its facilities would not facilitate a massive influx of Air Force and Army units.

At the National Military Command Center (aka the “Tank”) in the Pentagon, several major challenges were immediately apparent to the planners in response to the impending invasion. In addition to the port closures on the East Coast and the Port Arthur causeway bridge collapse, the interstate closures on I-95, I-26, and I-40 in the Carolinas were going to seriously impede military movement from Fort Bragg to Charleston and Wilmington. The causeway bridge collapse meant that Fort Hood units would need a different port to deploy from. While the 82nd Airborne Division’s Ready Brigade could deploy via airlift within 18 hours of notification, the flow of follow-on forces was going to be seriously delayed. Further, planners at XVIII Airborne Corps headquarters were uncertain where the paratroopers would be able to land: Was it going to be on Taiwan proper? If Chinese forces held the airport in force, the All-Americans would be quickly outnumbered and overwhelmed. The southernmost Okinawan Island of Ishigaki had only a small airport. Its facilities would not facilitate a massive influx of Air Force and Army units.

In addition, the 9,000 soldiers from the 1st Cavalry Division deployed to the southern border at Fort Bliss were going to have to be redeployed to Fort Hood to begin mobilization and deployment procedures.

As situation reports came into the “Tank” from XVIII Airborne Corps and III Armored Corps, there was a clear issue with communications. Cellular coverage was either diminished or non-existent. In addition, electrical outages around Fayetteville combined with the outer bands of rain were wreaking havoc on the mobilization of the 82nd Division’s Ready Brigade. As the winds picked up, the Air Force was reporting that their airlift might not be able to lift off.

INDOPACOM’s crisis plan called for the deployment of the III Marine Expeditionary Force based on Okinawa and the 25th Infantry Division from Hawaii to conduct landings on Taiwan to reinforce the Republic of China Armed Forces of some 150,000 active duty service members and up to 1.6M reservists. The question now was whether it would be a permissive, semi-permissive or non-permissive operational environment. As the combatant commander, the Commander, INDOPACOM, was worried about the ability of the Army and the Marines to bring in follow-on forces. The other issue was that both initial response forces were light infantry units — without significant armored support. That would come from III Armored Corps at Ft. Hood.

INDOPACOM’s crisis plan called for the deployment of the III Marine Expeditionary Force based on Okinawa and the 25th Infantry Division from Hawaii to conduct landings on Taiwan to reinforce the Republic of China Armed Forces of some 150,000 active duty service members and up to 1.6M reservists. The question now was whether it would be a permissive, semi-permissive or non-permissive operational environment. As the combatant commander, the Commander, INDOPACOM, was worried about the ability of the Army and the Marines to bring in follow-on forces. The other issue was that both initial response forces were light infantry units — without significant armored support. That would come from III Armored Corps at Ft. Hood.

INDOPACOM also needed to secure an intermediate staging base because of the uncertainty of the operational environment. The Commander, INDOPACOM, was concerned about the transit time of maritime lift from Okinawa to Taiwan of between sixteen to nineteen hours. Convoys would be vulnerable during this time and the loss of personnel and equipment could be devastating.

These are the challenges that the U.S. military could face when called upon to mobilize and deploy from a contested homeland and stage into a potentially hostile area:

-

- A confluence of natural disasters which impact airfields, ports, highways and other deployment infrastructure for extended periods of time.

- Manmade incidents or accidents which cause the same types of impediments.

- A vulnerable communications network, which, if interrupted, could cause military units to seek alternative means, including analog.

- Other deployments or commitments of units, which would require significant lead time to re-deploy to home-station and begin the deployment process again.

- An inadequate Intermediate Staging Base for responding forces to combat load and prepare for operations.

If you enjoyed this post, review the TRADOC Pamphlet 525-92, The Operational Environment 2024-2034: Large-Scale Combat Operations

Explore the TRADOC G-2‘s Operational Environment Enterprise web page, brimming with authoritative information on the Operational Environment and how our adversaries fight, including:

Our China Landing Zone, full of information regarding our pacing challenge, including ATP 7-100.3, Chinese Tactics, How China Fights in Large-Scale Combat Operations, BiteSize China weekly topics, and the People’s Liberation Army Ground Forces Quick Reference Guide.

Our Russia Landing Zone, including the BiteSize Russia weekly topics. If you have a CAC, you’ll be especially interested in reviewing our weekly RUS-UKR Conflict Running Estimates and associated Narratives, capturing what we learned about the contemporary Russian way of war in Ukraine over the past two years and the ramifications for U.S. Army modernization across DOTMLPF-P.

Our Iran Landing Zone, including the Iran Quick Reference Guide and the Iran Passive Defense Manual (both require a CAC to access).

Our North Korea Landing Zone, including Resources for Studying North Korea, Instruments of Chinese Military Influence in North Korea, and Instruments of Russian Military Influence in North Korea.

Our Irregular Threats Landing Zone, including TC 7-100.3, Irregular Opposing Forces, and ATP 3-37.2, Antiterrorism (requires a CAC to access).

Our Running Estimates SharePoint site (also requires a CAC to access) — documenting what we’re learning about the evolving OE. Contains our monthly OE Running Estimates, associated Narratives, and the quarterly OE Assessment TRADOC Intelligence Posts (TIPs).

Then read the following related Mad Scientist Laboratory content:

Tyranny of Time & Distance: Logistics & Contested Deployment in LSCO, by Stewart Bentley

The Hard Part of Fighting a War: Contested Logistics

In the Crosshairs: U.S. Homeland Infrastructure Threats

Weaponized Information: One Possible Vignette

Three Dates, Three Windows, and All of DOTMLPF-P, China and Russia: Achieving Decision Dominance and Information Advantage, and “No Option is Excluded” — Using Wargaming to Envision a Chinese Assault on Taiwan, by Ian Sullivan

Flash-Mob Warfare: Whispers in the Digital Sandstorm (Parts 1 and 2) and 50 Shades of JIFCO, by Dr. Robert E. Smith

Fait Accompli: China’s Non-War Military Operations (NWMO) and Taiwan, by SGT Michael A. Cappelli II

Operation Northeast Monsoon: The Reunification of Taiwan, by Sherman Barto

The Most Consequential Adversaries and associated podcast, with GEN Charles A. Flynn

Volatility in the Pacific: China, Resilience, and the Human Dimension and associated podcast, with General Robert Brown (USA-Ret.)

How China Fights and associated podcast

China’s PLA Modernization through the DOTMLPF-P Lens, by Dr. Jacob Barton

China: Building Regional Hegemony and China 2049: The Flight of a Particle Board Dragon, the comprehensive report from which this post was excerpted

Competition and Conflict in the Next Decade

Disrupting the “Chinese Dream” – Eight Insights on how to win the Competition with China

About the Author: Dr. Stewart Bentley is a military analyst studying Army deployment trends at the Deployment Process Modernization Office, CASCOM TRADOC. He is a prior service Infantry and Military Intelligence officer with a Masters in Strategic Intelligence from the National Intelligence University.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).