[Editor’s Note: As noted in the Contested Logistics section of TRADOC Pam 525-92, The Operational Environment 2024-2034: Large-Scale Combat Operations:

“The increased logistics requirements of LSCO will challenge Army sustainment operations, and adversaries will target those same operations from the Homeland to the battlefield.“

Army Mad Scientist welcomes guest blogger Dr. Stewart Bentley with his insightful post exploring the challenges of sustainment during contested deployment in LSCO. Looking back to the Second World War’s European and Pacific Theaters of Operation, Dr. Bentley examines the enduring lessons these 80-year-old campaigns have for us in the Twenty-first Century Operational Environment (OE). Recognizing that strategic airlift, battlefield automation, complex fires across multiple domains, and the loss of sanctuary (China, our pacing threat, can reach out and disrupt our flow Soldiers and materiel from fort to port to theater) are contemporary realities of LSCO — the enduring requirement to project and sustain expeditionary forces and the twin tyrannies of time and distance remain immutable — Read on!]

The Army is currently working to conceptualize the Operational Environment beginning with contested deployment for LSCO. The threats the Army could face throughout the mobilization and deployment process — from fort to port to Reception, Staging, Onward Movement, and Integration (RSOI) in theater — range from the non-kinetic (influence operations and cyberattacks) to kinetic fires (including small scale to saturation and even swarming strikes) across multiple domains. In addition, the Army has conducted few large-scale deployments over the past twenty years — focusing mostly on Brigade Combat Team (BCT) rotations. Finally, the Army has not faced a contested deployment environment (i.e., operating in a semi-permissive or non-permissive environment) since World War Two. There are lessons to be learned from that war, both in the European and the Pacific Theater of Operations (ETO/PTO).

The Army is currently working to conceptualize the Operational Environment beginning with contested deployment for LSCO. The threats the Army could face throughout the mobilization and deployment process — from fort to port to Reception, Staging, Onward Movement, and Integration (RSOI) in theater — range from the non-kinetic (influence operations and cyberattacks) to kinetic fires (including small scale to saturation and even swarming strikes) across multiple domains. In addition, the Army has conducted few large-scale deployments over the past twenty years — focusing mostly on Brigade Combat Team (BCT) rotations. Finally, the Army has not faced a contested deployment environment (i.e., operating in a semi-permissive or non-permissive environment) since World War Two. There are lessons to be learned from that war, both in the European and the Pacific Theater of Operations (ETO/PTO).

Despite extensive advance planning by the War Department, even prior to World War Two 1, fluid combat situations — combined with geographic and weather considerations — against formidable enemies, meant that a certain level of improvisation was required to overcome various friction points.

In the ETO, the largest contested deployment environment the Allies had to contend with was the Atlantic Ocean. Overcoming the threat was a huge challenge for the U.S. Navy and Britain’s Royal Navy. Convoy operations were an improvised response to defend merchant marine vessels against the German U-Boat threat. However, the convoy system was not adopted until the spring of 1941 — after millions of tons of supplies and thousands of merchant marine sailors had died during the initial stages of the Battle of the Atlantic.

In the ETO, the largest contested deployment environment the Allies had to contend with was the Atlantic Ocean. Overcoming the threat was a huge challenge for the U.S. Navy and Britain’s Royal Navy. Convoy operations were an improvised response to defend merchant marine vessels against the German U-Boat threat. However, the convoy system was not adopted until the spring of 1941 — after millions of tons of supplies and thousands of merchant marine sailors had died during the initial stages of the Battle of the Atlantic.

The Allies conducted several non-permissive amphibious operations during the period 1942-1944 with Operation Overlord (D-Day) being the largest and arguably the most consequential one in the ETO. Overlord could never have been executed without the enormous staging area provided by the United Kingdom. Following two years of planning, even with the impact of the Mediterranean landings, the U.S. Army alone had assembled over 1.5 million Soldiers with 144,000 tons of supplies pre-loaded and an additional stockpile of 2.5 million tons of equipment for follow-on operations.2

The Allies conducted several non-permissive amphibious operations during the period 1942-1944 with Operation Overlord (D-Day) being the largest and arguably the most consequential one in the ETO. Overlord could never have been executed without the enormous staging area provided by the United Kingdom. Following two years of planning, even with the impact of the Mediterranean landings, the U.S. Army alone had assembled over 1.5 million Soldiers with 144,000 tons of supplies pre-loaded and an additional stockpile of 2.5 million tons of equipment for follow-on operations.2

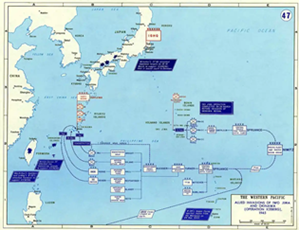

In the PTO, amphibious landings in non-permissive environments were the rule against determined Japanese resistance. The largest and perhaps most relevant landing to discuss here is the Okinawa operation, codenamed Iceberg. That invasion called for the use of the Tenth Army with one Army Corps (XXIVth), consisting of four Army divisions, and one Marine corps (III Amphibious), consisting of three  Marine divisions. Planning and coordination for the operation was extraordinary: “For the assault echelon alone, about 183,000 troops and 747,000 measurement tons of cargo were loaded into over 430 assault transports and landing ships at 11 different ports, from Seattle to Leyte, a distance of 6,000 miles.”3 This distance is contrasted with the comparatively short hop across the English Channel from Portsmouth to Normandy of between 100-130 miles.

Marine divisions. Planning and coordination for the operation was extraordinary: “For the assault echelon alone, about 183,000 troops and 747,000 measurement tons of cargo were loaded into over 430 assault transports and landing ships at 11 different ports, from Seattle to Leyte, a distance of 6,000 miles.”3 This distance is contrasted with the comparatively short hop across the English Channel from Portsmouth to Normandy of between 100-130 miles.

A strategic consideration for the Allies was the tyranny of distance; supplying the invasion force meant a crossing of a minimum of five days sailing time from the Marianas, which offered the nearest available port. Shipping from the West Coast entailed 26 days of sailing time across 6,250 miles — depending on the port. This tyranny of distance and time also impacted requisitioning, procurement, manifesting and loading.

Because of logistical considerations, the initial plan for the invasion of Okinawa called for the seizure of the southernmost Ryukyu Islands of Kerama and Keise nearby to establish base operations. This would facilitate the main invasion force by providing: “…a base for logistic support of fleet units, a protected anchorage, and a seaplane base.”4

Because of logistical considerations, the initial plan for the invasion of Okinawa called for the seizure of the southernmost Ryukyu Islands of Kerama and Keise nearby to establish base operations. This would facilitate the main invasion force by providing: “…a base for logistic support of fleet units, a protected anchorage, and a seaplane base.”4

A common Allied practice during operations in the PTO was that almost as soon as landings had taken place (even before combat operations had ceased), existing airfields were repaired or improved, and new fields were built. This practice extended to ports and docks in harbors previously occupied by the Japanese. The Allies’ ability to sustain their combat forces, even in the face of determined Japanese resistance, and interdict enemy reinforcement was key to Allied victory.

The lack of logistical infrastructure on remote South Pacific islands, unlike the established ones in Western Europe, meant that the Allies had to improvise solutions to meet the demands.

As might have been expected (in what will ring true today for planners), there was a significant shortfall of available sealift (for both strategic and littoral waters). The supply chain that resourced the Tenth Army stretched back to not only to South Pacific bases, but to the American West Coast. Strategic airlift, as it is recognized today, did not exist. Of note, mitigating lengthy supply lines had the invasion force taking a 30-day supply of rations, essential clothing and equipment, fuel, and medical and construction supplies.”5

As might have been expected (in what will ring true today for planners), there was a significant shortfall of available sealift (for both strategic and littoral waters). The supply chain that resourced the Tenth Army stretched back to not only to South Pacific bases, but to the American West Coast. Strategic airlift, as it is recognized today, did not exist. Of note, mitigating lengthy supply lines had the invasion force taking a 30-day supply of rations, essential clothing and equipment, fuel, and medical and construction supplies.”5

F or planners today, the ability to adequately forecast and requisition all classes of supplies, match them with available lift assets, and move them into theater should be a priority for combatant commands and supporting commands.

or planners today, the ability to adequately forecast and requisition all classes of supplies, match them with available lift assets, and move them into theater should be a priority for combatant commands and supporting commands.

In a forced entry, non-permissive environment, ships and aircraft will have to be combat loaded — with the expectation of Soldiers being prepared to fight upon landing. This places a premium on: 1) being able to expand and reinforce any lodgment, and 2) where to do the strategic to operational hand-off with watercraft and when to stow as combat loaded forces. Airfield seizures and securing port facilities should take precedence in planning considerations. This is where advanced knowledge of existing infrastructure plays a key role. Geography does not change: Deep water harbors and airfields capable of hosting American lift assets can be readily identified and categorized based on capabilities.

However, those same locations will likely be identified by aggressive nation states as “high value” targets with which to disrupt America’s ability to deploy into theater and subsequently sustain its forces. This same mindset also puts CONUS-based deployment and supply chain infrastructure at risk as the non-kinetic to kinetic threat stretches back to the homeland.

However, those same locations will likely be identified by aggressive nation states as “high value” targets with which to disrupt America’s ability to deploy into theater and subsequently sustain its forces. This same mindset also puts CONUS-based deployment and supply chain infrastructure at risk as the non-kinetic to kinetic threat stretches back to the homeland.

The proximity of permissive environment staging areas will also be a primary consideration for logistical support, as well as the ability to tactically support the landing and interdict threat reinforcements.

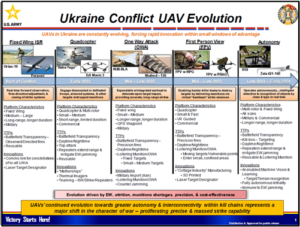

The recent advent of masses of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) carrying out saturation strikes in the Operational Environment presents its own unique challenges. The widespread proliferation of armed UAVs which are relatively cheap to procure and difficult to defend against, as seen in the Ukraine war, calls for the development and employment of layered, organic, and mobile counter-unmanned aerial system (C-UAS) capabilities across all unit levels. The Army is already deploying UAVs for reconnaissance and surveillance at the unit level; countering this same threat requires emerging technologies — both kinetic and electromagnetic. This C-UAS requirement, however, will also add to the training and logistical challenges facing our Soldiers.

An important consideration is that LSCO will be a dynamic environment which rapidly changes and results in often unpredictable outcomes. Any LSCO opponent can be expected to react and adapt in the face of setbacks and tactical reverses. A LSCO opponent will face the same difficulties in overcoming geography, weather, and the competition for resources as the U.S. military.

Planning today against China, our pacing threat — or worse, against adversarial collusion between members of the “Axis of Upheaval” — in a contested deployment environment will mean facing a variety of threats during the mobilization and movement process and beyond. Anything that would hinder or affect information networks (cyber) or physical infrastructure (sabotage) should be taken into consideration for force protection during the mobilization process. During the movement and RSOI processes, that interference will more likely be kinetic. The ability to adapt deployment processes to adjust to changing circumstances will also require creativity and command flexibility. While obvious changes as far as strategic airlift and information technology have added different dimensions to the deployment process, the need to overcome the tyranny of distance and time remains as critical today as it did in 1944 and 1945.

Planning today against China, our pacing threat — or worse, against adversarial collusion between members of the “Axis of Upheaval” — in a contested deployment environment will mean facing a variety of threats during the mobilization and movement process and beyond. Anything that would hinder or affect information networks (cyber) or physical infrastructure (sabotage) should be taken into consideration for force protection during the mobilization process. During the movement and RSOI processes, that interference will more likely be kinetic. The ability to adapt deployment processes to adjust to changing circumstances will also require creativity and command flexibility. While obvious changes as far as strategic airlift and information technology have added different dimensions to the deployment process, the need to overcome the tyranny of distance and time remains as critical today as it did in 1944 and 1945.

If you enjoyed this post, review the TRADOC Pamphlet 525-92, The Operational Environment 2024-2034: Large-Scale Combat Operations

Explore the TRADOC G-2‘s Operational Environment Enterprise web page, brimming with authoritative information on the Operational Environment and how our adversaries fight, including:

Our China Landing Zone, full of information regarding our pacing challenge, including ATP 7-100.3, Chinese Tactics, BiteSize China weekly topics, People’s Liberation Army Ground Forces Quick Reference Guide, and our thirty-plus snapshots captured to date addressing what China is learning about the Operational Environment from Russia’s war against Ukraine (note that a DoD Common Access Card [CAC] is required to access this last link).

Our Russia Landing Zone, including the BiteSize Russia weekly topics. If you have a CAC, you’ll be especially interested in reviewing our weekly RUS-UKR Conflict Running Estimates and associated Narratives, capturing what we learned about the contemporary Russian way of war in Ukraine over the past two years and the ramifications for U.S. Army modernization across DOTMLPF-P.

Our Iran Landing Zone, including the latest Iran OE Watch articles, as well as the Iran Quick Reference Guide and the Iran Passive Defense Manual (both require a CAC to access).

Our Running Estimates SharePoint site (also requires a CAC to access) — documenting what we’re learning about the evolving OE. Contains our monthly OE Running Estimates, associated Narratives, and the 2QFY24, 3QFY24, 4QFY24, and 1QFY25 OE Assessment TRADOC Intelligence Posts (TIPs).

Then check out the following related Mad Scientist Laboratory content:

The Hard Part of Fighting a War: Contested Logistics

Operation Northeast Monsoon: The Reunification of Taiwan, by Sherman Barto

Weapons on Demand: How 3D Printing Will Revolutionize Military Sustainment, by Scott Pettigrew

Sinews of War: Innovating the Future of Sustainment by then MSG Donald R. Cullen, MSG Timothy D. Roberts, MSG Jessica Cho, and MSG Johanny Ortega

In the Crosshairs: U.S. Homeland Infrastructure Threats

Weaponized Information: One Possible Vignette

The Most Consequential Adversaries and associated podcast, with GEN Charles A. Flynn

Volatility in the Pacific: China, Resilience, and the Human Dimension and associated podcast, with General Robert Brown (USA-Ret.)

How China Fights and associated podcast

China’s PLA Modernization through the DOTMLPF-P Lens, by Dr. Jacob Barton

Three Dates, Three Windows, and All of DOTMLPF-P, China and Russia: Achieving Decision Dominance and Information Advantage, and “No Option is Excluded” — Using Wargaming to Envision a Chinese Assault on Taiwan, by Ian Sullivan

Flash-Mob Warfare: Whispers in the Digital Sandstorm (Parts 1 and 2), by Dr. Robert E. Smith

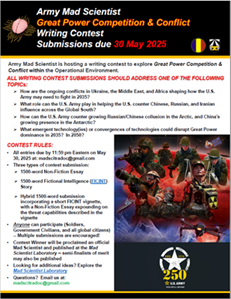

>>>>Reminder: Army Mad Scientist wants to crowdsource your thoughts on Great Power Competition & Conflict — check out the flyer describing our latest writing contest.

>>>>Reminder: Army Mad Scientist wants to crowdsource your thoughts on Great Power Competition & Conflict — check out the flyer describing our latest writing contest.

All entries must address one of the following writing prompts:

How are the ongoing conflicts in Ukraine, the Middle East, and Africa shaping how the U.S. Army may need to fight in 2035?

What role can the U.S. Army play in helping the U.S. counter Chinese, Russian, and Iranian influence across the Global South?

How can the U.S. Army counter growing Russian/Chinese collusion in the Arctic, and China’s growing presence in the Antarctic?

What emergent technology(ies) or convergences of technologies could disrupt Great Power dominance in 2035? In 2050?

We are accepting three types of submissions:

-

-

- 1500-word Non-Fiction Essay

-

-

-

- 1500-word Fictional Intelligence (FICINT) Story

-

-

-

- Hybrid 1500-word submission incorporating a short FICINT vignette, with a Non-Fiction Essay expounding on the threat capabilities described in the vignette

-

Anyone can participate (Soldiers, Government Civilians, and all global citizens) — Multiple submissions are encouraged!

All entries are due NLT 11:59 pm Eastern on May 30 , 2025 at: madscitradoc@gmail.com

Click here for additional information on this contest — we look forward to your participation!

About the Author: Dr. Stewart Bentley is a military analyst studying Army deployment trends at the Deployment Process Modernization Office, CASCOM TRADOC. He is a prior service Infantry and Military Intelligence officer with a Masters in Strategic Intelligence from the National Intelligence University.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

1 Matloff, Maurice; Snell, Edwin (1952). Strategic Planning for Coalition Warfare, 1941-1942. US Army Center for Military History, 14 December 1951. Retrieved on 3 July 2024. Page 6.

2 Omaha Beachhead: 6 June-13 June 1944 (American Forces in Action Series) US Army Center for Military History. 20 September 1945, retrieved on 1 July 2024. Page 2.

3 Appleman, Roy; Burns, James; Gugeler, Russel; Stevens, John (1948). Okinawa: The Last Battle. United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 1410222063. Archived from the original on 8 November 2010. Retrieved 1 July, 2024. Page 36.

4 Ibid. Page 30.

5 Ibid. Page 37-8.