[Editor’s Note: The Mad Scientist Laboratory welcomes guest blogger Ted Hallum, Senior Defense Machine Learning Engineer, oLabs’ AI Center of Excellence, Octo, with today’s post proposing a scalable solution to the World Economic Forum‘s stark prediction that the implementation of machine learning and other AI technologies will displace 85 million jobs worldwide by 2025. The U.S. Army faces a similar challenge with its rapid force modernization requiring new skill sets (including AI) for its workforce of Soldiers and DA civilians spanning five generations in the decade ahead. Recognizing that one size will not fit all (many Generation Z and Alpha recruits and interns will come to the force  inherently technologically-savvy as New Humans), Mr. Hallum’s exploration of Amazon‘s Upskilling 2025 Program provides a viable use case for ensuring that the U.S. workforce, and U.S. Army in particular, is AI Ready!]

inherently technologically-savvy as New Humans), Mr. Hallum’s exploration of Amazon‘s Upskilling 2025 Program provides a viable use case for ensuring that the U.S. workforce, and U.S. Army in particular, is AI Ready!]

Barring extreme wartime circumstances and invocation of the Defense Production Act, would consumer automobile manufacturers choose to build M1 Abrams tanks? Not likely, because the market dictates that these companies must operate on a low-margin / high-volume business model to succeed. So, for these automotive companies, manufacturing M1 Abrams tanks would not be profitable.

Yet, the United States needs competently produced and mechanically sound tanks for national security. So, how does the nation procure them? This question invokes the economic functions of government, specifically function #3: “Provide Public Goods & Services.” Within the context of this function, “Public goods and services are those that markets will not provide in sufficient quantities.” Most commonly, this means the government must cultivate the circumstances or environment necessary for the good or service to be market viable.

M1 Abrams tanks become market viable in precisely this manner. The federal government owns the Joint Systems Manufacturing Center – Lima (JSMC, aka Lima Army Tank Plant), a 1.6 million square foot manufacturing facility in Lima, Ohio. General Dynamics Land Systems (GDLS) is a niche manufacturer of military vehicles. The government makes the JMSC available to GDLS, creating the circumstances necessary for GDLS to profitably produce tanks on the government’s behalf and fulfill a national security need.

M1 Abrams tanks become market viable in precisely this manner. The federal government owns the Joint Systems Manufacturing Center – Lima (JSMC, aka Lima Army Tank Plant), a 1.6 million square foot manufacturing facility in Lima, Ohio. General Dynamics Land Systems (GDLS) is a niche manufacturer of military vehicles. The government makes the JMSC available to GDLS, creating the circumstances necessary for GDLS to profitably produce tanks on the government’s behalf and fulfill a national security need.

So, what is the commonality between M1 Abrams tanks and Artificial Intelligence (AI)? The answer is, “more than you might think.” Looking toward the future, AI will radically change the face of war – and society at large. From a combat standpoint, one military futurist felt compelled to say that future international actors “will compete not for the most powerful weapon, but for the most optimized AI-driven battlefield commander algorithm. This will give tremendous advantages in combat, harvesting the AI’s decision-making speed and optimized strategies.” Concerning broader societal implications, some of our era’s most profound and visionary minds have mixed enthusiasm and grave reservations about AI and how it will increasingly impact more granular aspects of our human experience.

On the Cusp: Imminent Need for Dramatic Upskilling

One of the most pressing of these concerns is continued gainful employment for the broadest swath of the workforce. The World Economic Forum (WEF) predicts a mix of bad and good news. According to the Future of Jobs Report 2020, the WEF expects the implementation of machine learning and other AI technologies to displace 85 million jobs worldwide by 2025. The WEF adds that COVID-19 has accelerated the adoption of automation in many industries. As for the good news, the WEF expects these technologies to more than offset those losses by creating 97 million new jobs – which, of course, will only apply to those possessing the requisite AI-era skills.

One of the most pressing of these concerns is continued gainful employment for the broadest swath of the workforce. The World Economic Forum (WEF) predicts a mix of bad and good news. According to the Future of Jobs Report 2020, the WEF expects the implementation of machine learning and other AI technologies to displace 85 million jobs worldwide by 2025. The WEF adds that COVID-19 has accelerated the adoption of automation in many industries. As for the good news, the WEF expects these technologies to more than offset those losses by creating 97 million new jobs – which, of course, will only apply to those possessing the requisite AI-era skills.

In 2025, the United States will likely have a workforce population totaling ~221.4 million people. Assuming WEF projections are correct, just shy of 100 million members of the United States’ workforce (45%) will need 6+ months of upskilling within the next four years.

So, for the foreseeable future broadscale gainful employment remains a realistic goal, but transforming the workforce to meet this shifting demand will require a societal-level, government-backed emphasis on upskilling. On this point, the WEF warns that the monumental shift in skill demand “will require businesses and governments to collaborate on massive  reskilling and upskilling initiatives…. The rapid pace of technological change requires new models for training that prepare employees for an AI-based future.”

reskilling and upskilling initiatives…. The rapid pace of technological change requires new models for training that prepare employees for an AI-based future.”

Is Government Intervention to Drive Upskilling Appropriate?

Dramatically changing the face of war is not the only thing that M1 Abrams tanks and AI will have in common. Similar to the production of M1 Abrams tanks, the availability of AI expertise will also be a national need “that markets will not provide in sufficient quantities.” So, the 3rd economic function of government once again applies.

However, function #3 cannot justify government intervention to the extent necessary because it only addresses the U.S. Government’s responsibility to make AI expertise sufficiently available for “public service” rather than for American society as a whole.

The United States is a market-driven economy. So, from the standpoint of national economic stability, what if the United States’ supply of AI-era workers cannot adequately meet demand? Exactly how much is at stake? According to  Guy Berger, Principal Economist at LinkedIn, AI is expected “to add $13 trillion to current global economic output by 2030” (an increase of ~16%). Therefore, countries that invest in building sufficiently sized and skilled AI-era workforces will be well-postured to secure an outsized share of this massive increase in global economic output.

Guy Berger, Principal Economist at LinkedIn, AI is expected “to add $13 trillion to current global economic output by 2030” (an increase of ~16%). Therefore, countries that invest in building sufficiently sized and skilled AI-era workforces will be well-postured to secure an outsized share of this massive increase in global economic output.

Another economic function of government becomes applicable when considering these potential society-wide benefits. Function #4(b) states: “Correct for Externalities – Encourage increased production of goods and services that have positive externalities.” In layman’s terms, this means that the government is “in the right” to bolster the production of goods or availability of services when they yield benefits that “spillover” to society in general. Given how AI is poised to increase global economic output, any U.S. Government effort to fund or subsidize upskilling programs would produce these kinds of society-wide benefits.

So, two economic functions of government, namely #3 and #4b, provide justification and imperative for the U.S. Government to cultivate the circumstances necessary to achieve an ample AI-era workforce by 2025.

Best-blend of Government/Private Sector to Build an AI-era Workforce

So, what approach should the U.S. Government reasonably take to successfully upskill such a large percentage of its workforce within such a constrained period?

Luckily, an existing body of research and experience from a relevant source provides a promising template.

Dr. Terrence Sejnowski co-invented Boltzmann Machines (a type of artificial neural network) with Geoffrey Hinton in 1985. More applicably to the problem of workforce upskilling, Dr. Sejnowski helped establish and run UC San Diego’s  Temporal Dynamics of Learning Center (TDLC) in 2006 and still serves as the center’s Senior Advisor for External Partnerships and Programs.

Temporal Dynamics of Learning Center (TDLC) in 2006 and still serves as the center’s Senior Advisor for External Partnerships and Programs.

Dr. Sejnowski’s work with the TDLC led him to co-develop a Massively Open Online Course (MOOC) called Learning How to Learn. This course has enrolled over 2.7 million learners. Moreover, learners can complete the course with a digital certificate for only $49. While these outcomes are compelling, Dr. Sejnowski did not originally envision deploying his curriculum as a MOOC. It was more of a fortuitous last resort!

Dr. Sejnowski’s reflections on deciding to use the MOOC delivery model are informative:

“Ah, here’s what I learned…Delivering was incredibly difficult because of all the barriers. There are gatekeepers at every step. There are 12,000 school districts in the United States and if you needed to take some software into a classroom, you’re going to [have to] knock on 12,000 doors…So, this [MOOC] taught us…that the way that you get into people’s homes is to bypass all the gatekeepers and go directly through the internet…don’t try to reform the system.”

Other attributes of the MOOC model are attractive, in addition to scalability and affordability. First, numerous private MOOC platforms already exist. Many offer very high-quality curricula created by industry experts (e.g., deeplearning.ai/Andrew Ng) or highly ranked universities (e.g., Stanford). Leveraging private MOOC platforms’ pre-existing infrastructure and their course offerings eliminates the time and complexity costs otherwise incurred by attempting to leverage conventional education institutions, building a government-operated online learning platform, etc.

Taking on the perspective of the U.S. Government, it seems that leveraging the MOOC model would reduce the scope of this problem down to roughly five elements:

1) Educating/motivating the workforce to upskill

2) Assisting the workforce with MOOC selection by mapping their interests/career goals to in-demand skillsets and funded upskilling opportunities

3) Educating employers about the validity of MOOC education

4) Effectively implementing funding/subsidies

5) Establishing a filter to ensure that only reputable, high-quality MOOCs are funding-eligible

Educate and Motivate the Workforce to Pursue Upskilling

Providing funding and making appropriate training available/accessible will not be enough. Lessons learned from Amazon’s Upskilling 2025 Program are insightful on this point. Notably, some members of the workforce do not understand the imminent need to upskill. Other portions of the workforce perhaps generally realize change is on the horizon, but do not know which skills to pursue.

Providing funding and making appropriate training available/accessible will not be enough. Lessons learned from Amazon’s Upskilling 2025 Program are insightful on this point. Notably, some members of the workforce do not understand the imminent need to upskill. Other portions of the workforce perhaps generally realize change is on the horizon, but do not know which skills to pursue.

Therefore, strategic messaging should: 1) clarify that upskilling is critical, and 2) help members of the workforce map their interests, professional goals, etc., to skillsets that are AI-era relevant.

This need to inform the workforce would be best served by a federally spearheaded information campaign in concert with a supportive grassroots movement to fan the flames.

To this day, many American parents routinely instruct their children to “clean their plates” – for some, it is almost instinct or a moral imperative. However, most of these parents are unaware that this “instinct” is a descendent of Herbert Hoover’s exceptionally effective “Clean Plate” campaign and the grassroots movement that fueled it. The campaign launched in 1917 and successfully shaped individual behavior to conserve diminishing national food supplies during World War I.

To build an AI-era workforce by 2025, the United States will require an equally impactful information campaign.

Mapping Interests/Career Goals –> In-demand Skillsets –> Funding-eligible MOOCs

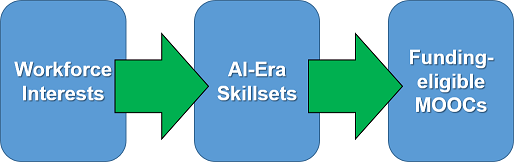

Complimentary to educating and motivating the workforce is the need to provide a tool to help workers map their interests/career goals to in-demand skillsets and funded upskilling opportunities. This mapping is useful because when people can conceptualize the link between their interests and new AI-era work realities, they are more likely to embrace the learning opportunity.

Toward this end, it would be beneficial for the U.S. Government to make available a web-based 2-stage index that first maps workforce interests to AI-era skillsets and then maps those skillsets to funding-eligible MOOCs.

Educating Employers About the Merits of MOOCs

While it is not surprising that some employers do not understand the merits of MOOCs, the Harvard Business Review (HBR) is an admittedly unexpected sounding horn. Nevertheless, HBR writes:

“[MOOCs] are readily available and relatively inexpensive…Course topics range from machine learning and Java programming to communication and leadership…In light of all this potential, why have organizations been so slow to embrace MOOCs?… One of the main reasons so many companies fail to capitalize on MOOCs’ training potential is a lack of awareness…[and] Companies also don’t seem to recognize MOOCs as a viable substitute for formal training.”

Ideally, a federally spearheaded information campaign like the one introduced above would dovetail messaging that targets both the workforce and industry. Messaging directed at employers should stress MOOC-acquired skills’ business value and encourage baking this awareness into talent acquisition pipelines.

Funding/Subsidies for MOOC Upskilling

Of course, before the U.S. Government can formulate a budget or appropriate funds, it must identify a useful heuristic function for projecting what an upskilling initiative of this size and scope might cost.

Considering that Amazon designed the Upskilling 2025 Program to upgrade skills across the breadth of its workforce, some specific information about the program is useful for devising a heuristic that should scale relatively well to the broader U.S. workforce.

First, Amazon set aside $700 million in 2019 to fund its upskilling program. Second, Amazon had ~750,000 employees in 2019. To obtain a rough average of the per-employee upskilling expense, we can calculate $700 million divided by 750,000 employees, which yields an average upskilling cost of ~$933 per employee.

So, ~$933 multiplied by the estimated 2025 U.S. workforce size of ~221,426,960 means that retooling the U.S. workforce for the AI-era should cost in the ballpark of $206.5 billion. [Editor’s Note: For comparison purposes, the U.S. Army’s total end strength for FY21 , which includes the National Guard and Reserve, is 1,012,200 Soldiers. Factor in an additional 330,000 plus for Department of Army civilians. Employing Amazon’s use case, the resulting ROM cost for retooling the entire Department of Army workforce  for the AI-era might cost ~ $1.252 billion. Recognizing that OMA and OPA are different funding sources, it is nonetheless illustrative to consider that the FY21 Program Acquisition Cost (see pp. 15-16) for the M1 Abrams Tank Modification / Upgrades is $1.509 billion, AH-64E Apache Remanufacture / New Build is $1.226 billion, Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System is $1.204 billion, Joint Light Tactical Vehicle is $1.372 billion, and Stryker is $1.116 billion. An additional consideration is that the entire workforce will not need re-tooling, as many Generation Z and Alpha recruits and interns will come to the force inherently technologically-savvy as New Humans.]

for the AI-era might cost ~ $1.252 billion. Recognizing that OMA and OPA are different funding sources, it is nonetheless illustrative to consider that the FY21 Program Acquisition Cost (see pp. 15-16) for the M1 Abrams Tank Modification / Upgrades is $1.509 billion, AH-64E Apache Remanufacture / New Build is $1.226 billion, Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System is $1.204 billion, Joint Light Tactical Vehicle is $1.372 billion, and Stryker is $1.116 billion. An additional consideration is that the entire workforce will not need re-tooling, as many Generation Z and Alpha recruits and interns will come to the force inherently technologically-savvy as New Humans.]

Federal funding or subsidy (“financial aid”) implementations could potentially take on many forms, but more consequential are the three most probable delivery avenues:

1) Provide financial aid directly to the learner.

2) Provide financial assistance through MOOC platforms.

3) Provide financial support directly to employers.

Providing aid directly to the learner is conceptually straightforward. This approach would necessitate the “tuition reimbursement” model to prevent fraud. In this scenario, once the learner completes training, they would submit a verifiable digital credential to the U.S. Government for reimbursement or include the digital credential in his/her annual federal income tax filing to receive an appropriate tax credit.

As an alternative, administering financial aid through MOOC platforms would be a wrinkle-free approach from the workforce’s perspective. With this approach, the U.S. Government would provide financial aid funds directly to MOOC platforms, eliminating the learner’s need to request reimbursement. MOOC platforms would then make funding-eligible course offerings available to U.S. workforce members for a free or reduced cost.

As a third option, distributing financial aid through employers would have both benefits and drawbacks. In this scenario, companies would accept money from the U.S. Government and apply it toward upskilling their employees (essentially functioning as financial aid brokers between the employees and the MOOC platforms). This approach’s primary appeal would be automatically ensuring the workforce conducts upskilling in proportion to market demand. However, this approach is likely to be viewed as cumbersome from the workforce perspective. Moreover, workforce members would likely pass-up “force-fed upskilling” opportunities that they do not find personally appealing or interesting.

Considering that most of the workforce needs to embrace this imperative to upskill, it would be advisable to select financial aid disbursement methods that encourage maximal workforce utilization (i.e., the workforce views as streamlined and empowering).

Establish a Filter: Only Fund or Subsidize Reputable, High-quality MOOCs

Any plan to drive upskilling via MOOCs would require a well-defined filter with specific criteria to prevent the inception of a multi-billion-dollar predatory industry. For the sake of time and the perennial wisdom of Occam’s razor, this author recommends keeping the filtering mechanism simple. A good strategy would be to rapidly vet MOOCs for funding eligibility by measuring them against three straightforward prerequisite criteria:

1) Does the MOOC come with a verifiable digital credential?

2) Does the MOOC offer a skillset that is relevant to the AI-era?

3) Was the MOOC produced by industry experts or colleges/universities that are highly reputable, regionally accredited, and non-profit?

Key Takeaways

Similar to M1 Abrams tanks, The United States requires an AI-era workforce for its enduring national security. Additionally, our national economic stability for 2025 and beyond critically depends upon building a workforce possessing AI-era competencies. However, to succeed, this nation-wide upskilling endeavor must be characterized by unprecedented scope and pace.

Successful retooling of the U.S. workforce within these constraints will only be possible within the context of a combined effort between the government and the private sector. A best-blend approach would leverage the private sector’s existing infrastructure of MOOC platforms in concert with U.S. Government provided financial aid to make specific funding-eligible MOOCs available at a free or reduced cost. The U.S. Government would also fulfill other functions related to appropriately educating the workforce and industry, helping the workforce map interests to AI-era relevant upskilling opportunities, and screening MOOCs for verifiability/credibility.

Conventional education approaches would take too long and cost too much. By contrast, this approach can scale to achieve an AI-era workforce for the United States by 2025.

If you enjoyed this post, check out the following:

U.S. Demographics, 2020-2028: Serving Generations and Service Propensity

New Skills Required to Compete & Win in the Future Operational Environment

BrAIn Gain > BrAIn Drain: Strategic Competition for Intellect

Artificial Intelligence: An Emerging Game-changer

Integrating Artificial Intelligence into Military Operations, by Dr. James Mancillas

“Own the Night” and the associated Modern War Institute podcast with proclaimed Mad Scientist Mr. Bob Work

… and read the following posts and listen to the associated “The Convergence“ podcasts:

The Convergence: The Language of AI with Michael Kanaan and associated podcast

The Convergence: AI Across the Enterprise with Rob Albritton and associated podcast

The Convergence: The Future of Talent and Soldiers with MAJ Delaney Brown, CPT Jay Long, and 1LT Richard Kuzma and associated podcast

The Convergence: Bringing AI to the Joint Force and associated podcast

>>> REMINDER: Our Mad Scientist Writing Contest on Competition, Crisis, Conflict, and Change seeks to crowdsource the intellect of the Nation (i.e., You!) regarding:

How will our competitors deny the U.S. Joint Force’s tactical, operational, and strategic advantages to achieve their objectives (i.e., win without fighting) in the Competition and Crisis Phases?

How will our adversaries seek to overmatch or counter U.S. Joint Force strengths in future Large Scale Combat Operations?

Submission guidelines are addressed on our contest flyer — you’ve got 5 days left — deadline for submission is 15 March 2021!!!

Ted Hallum is a Senior Defense Machine Learning Engineer within the oLabs’ AI Center of Excellence at Octo. He has prior service in the U.S. Army’s Military Intelligence Corps and holds a Master of Science in Business Analytics from the College of William & Mary.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).