The Mad Scientist Strategic Security Environment (SSE) 2050 Conference explored the thesis that the direction of global trends shaping the future Operational Environment (2030-2050), and the geopolitical situation that results from it, will lead to fundamental change in the character of war. Co-sponsored by the TRADOC G-2, the Chief of Staff of the Army’s (CSA) Strategic Studies Group (SSG), and Georgetown University’s Center for Security Studies, SSE 2050 informed us that our understanding of the future SSE must first be grounded on what will not change, particularly the enduring nature of war.

The Mad Scientist Strategic Security Environment (SSE) 2050 Conference explored the thesis that the direction of global trends shaping the future Operational Environment (2030-2050), and the geopolitical situation that results from it, will lead to fundamental change in the character of war. Co-sponsored by the TRADOC G-2, the Chief of Staff of the Army’s (CSA) Strategic Studies Group (SSG), and Georgetown University’s Center for Security Studies, SSE 2050 informed us that our understanding of the future SSE must first be grounded on what will not change, particularly the enduring nature of war.

War, intrinsic to the human condition, will persist as a fundamentally human activity, and because human nature is in turn enduring, so too is the nature of war.

War, intrinsic to the human condition, will persist as a fundamentally human activity, and because human nature is in turn enduring, so too is the nature of war.

Similarly, the U.S. has enduring interests out to 2050, but we can anticipate an accelerating collision of interests as peer competitors assert interests of their own, as do a wider range of threats including Violent Extremist Organizations (VEOs) and super-empowered individuals.

Similarly, the U.S. has enduring interests out to 2050, but we can anticipate an accelerating collision of interests as peer competitors assert interests of their own, as do a wider range of threats including Violent Extremist Organizations (VEOs) and super-empowered individuals.

These new warfare approaches leverage a series of extended and emerging trends. Extended trends are more readily amenable to long term forecasting; as humans respond to these extended trends, emerging trends become evident — less predictable, to be sure, but nonetheless discernible and significant. The following inexorable demographic and economic changes drive extended trends and are more readily amenable to long term forecasting and projection:

– Geography. Although we tend to view geography as somewhat immutable, even geography will not escape the impact of a global population that will have increased from 2.5 billion in 1950 to 9.5 billion in 2050. Development and climate change will alter even the fundamentals of geography, open arctic sea routes, and raise sea levels at the littorals. Cities will physically cover large areas of the globe with complex urban sprawl and incorporate a global population that will be 66% urbanized.

– Geography. Although we tend to view geography as somewhat immutable, even geography will not escape the impact of a global population that will have increased from 2.5 billion in 1950 to 9.5 billion in 2050. Development and climate change will alter even the fundamentals of geography, open arctic sea routes, and raise sea levels at the littorals. Cities will physically cover large areas of the globe with complex urban sprawl and incorporate a global population that will be 66% urbanized.  Some megacities will be more important politically and economically than many nation-states; others will out-grow their host state. The convergence of more information, more people, together with less community cohesion, state resources, and governance threaten rampant poverty, violence and pollution: a breeding ground for discontent and anger among an increasingly aware yet still dis-empowered population.

Some megacities will be more important politically and economically than many nation-states; others will out-grow their host state. The convergence of more information, more people, together with less community cohesion, state resources, and governance threaten rampant poverty, violence and pollution: a breeding ground for discontent and anger among an increasingly aware yet still dis-empowered population.

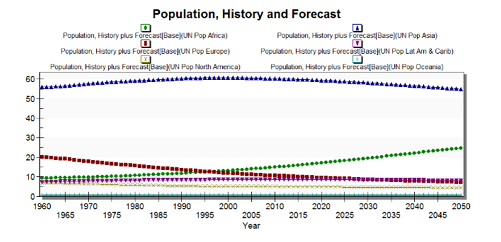

– Demographics. The increase in global population will be far from even: Africa’s population will rise, Europe’s will decline, as will East Asia, but at a lower rate. European and Asian population average ages will increase while Africa stays young. The disparate growth rates and average ages will drive the direction of migration, unemployment trends, and the availability (and inclination) of individuals fit for military service.

– Demographics. The increase in global population will be far from even: Africa’s population will rise, Europe’s will decline, as will East Asia, but at a lower rate. European and Asian population average ages will increase while Africa stays young. The disparate growth rates and average ages will drive the direction of migration, unemployment trends, and the availability (and inclination) of individuals fit for military service.

– Economics. The distribution of global wealth will become only slightly more equal over the next several decades  and this relative improvement will not occur evenly across the globe; the bottom 30% will not see any improvement in their relative economic position. Relative deprivation drives instability; not deprivation per se – and in a world increasingly connected regardless of income level, the deprived will be painfully aware of their relative status.

and this relative improvement will not occur evenly across the globe; the bottom 30% will not see any improvement in their relative economic position. Relative deprivation drives instability; not deprivation per se – and in a world increasingly connected regardless of income level, the deprived will be painfully aware of their relative status.

– Education. Education goes up everywhere, but regional differences continue to be significant.

The disparate access to quality education will drive uneven economic growth, and differentiate the benefits of participation in global trade.

– Water Scarcity. Pollution, contamination, and over-use of many critical water sources will increasingly render water a  “non-renewable” resource. Increasing scarcity may drive conflict. Water stress is already high in many portions of the globe, wide-spread water shortages are probable in 2050, with billions potentially impacted.

“non-renewable” resource. Increasing scarcity may drive conflict. Water stress is already high in many portions of the globe, wide-spread water shortages are probable in 2050, with billions potentially impacted.

– Food Scarcity. Certain segments of Africa will see food production significantly lag population growth, though the causes of food scarcity are likely to be domestic conflict, poor governance, and mismanagement rather than a lack of arable land. In 2016, the number of net food importing countries is growing while food price volatility is increasing. This scarcity – together with that of water — will also almost certainly create future migratory pressures and mass population movements, with destabilizing results in both the donor and recipient regions.

In 2016, the number of net food importing countries is growing while food price volatility is increasing. This scarcity – together with that of water — will also almost certainly create future migratory pressures and mass population movements, with destabilizing results in both the donor and recipient regions.

– Resource Competition. Growing and shifting populations will increasingly compete for water, food, fossil fuels, and unique mineral resources.

– Resource Competition. Growing and shifting populations will increasingly compete for water, food, fossil fuels, and unique mineral resources.

– Mass Migration. The National Intelligence Council predicts that 2030 will be characterized as the “new age of migration.” Driven by climate change, water and food scarcity, uneven economic opportunity, and political and social insecurity,

– Mass Migration. The National Intelligence Council predicts that 2030 will be characterized as the “new age of migration.” Driven by climate change, water and food scarcity, uneven economic opportunity, and political and social insecurity,  mass migration will pose a significant governance challenge to receiving states as these migrants concentrate predominantly in urban areas. Immigration can result in beneficial, synergistic blending of cultures, ethnicities, and ideologies as groups assimilate into their new region; alternately disparate cultures, ethnic tensions and stigmatizing stereotypes can force people into small enclaves, pockets and neighborhoods of ethnically homogenous migrants.

mass migration will pose a significant governance challenge to receiving states as these migrants concentrate predominantly in urban areas. Immigration can result in beneficial, synergistic blending of cultures, ethnicities, and ideologies as groups assimilate into their new region; alternately disparate cultures, ethnic tensions and stigmatizing stereotypes can force people into small enclaves, pockets and neighborhoods of ethnically homogenous migrants.  These isolated areas often suffer from less capable governance including law enforcement, sanitation services, and institutional education opportunities that lag behind most of the host country. The key is the rate at which an immigrant population can be assimilated; if that rate is exceeded, then the impact is destabilizing.

These isolated areas often suffer from less capable governance including law enforcement, sanitation services, and institutional education opportunities that lag behind most of the host country. The key is the rate at which an immigrant population can be assimilated; if that rate is exceeded, then the impact is destabilizing.

– Energy Demand. Energy demand will continue to rise but extended trends indicate that solutions will keep pace with that demand. Technologies ranging from fracking, fuel cells, controlled (and compact, mobile) nuclear fusion, ocean thermal energy conversions, biomass, and wind provide multiple options to supplement legacy power generation technologies and meet the inevitable rising energy demands of a growing world population. Some of these energy options, however, may exacerbate the extent and rate of climate change. The proliferation of alternative energy sources might suppress fossil fuel costs, impacting major producers whose economic well-being and stability is tied to continued global demand and production.

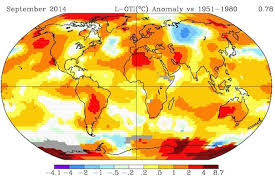

– Climate Change. Climate change is the great accelerator, exacerbating the impact of water shortages, food insecurity, and even geographic changes.

Our efforts to understand the future strategic security environment illustrate both the enduring nature of war and also the inevitable collision of interests between likely competitors, how our adversaries are adapting, and the extended trends that propel those adaptations. These trends propel our own need to adapt as well, and our understanding cannot be complete without rigorous self-examination.

For information on how these and other trends affect the Operational Environment, see the OEWatch, an open source, monthly publication published by the TRADOC G-2’s Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO).

FMSO also publishes a number of OE monographs, some of which address trends identified above, for example: The Rare Earth Dilemma: Trading OPEC for China.

Also see Dr. Jonathan D. Moyer’s presentation on Long Term Trends and Some Implications of Decreasing Global Interdependence from the SSE 2050 Conference.

“… the study concluded that autonomy will deliver substantial operational value across an increasingly diverse array of DoD missions, but the DoD must move more rapidly to realize this value. Allies and adversaries alike also have access to rapid technological advances occurring globally. In short, speed matters—in two distinct dimensions. First, autonomy can increase decision speed, enabling the U.S. to act inside an adversary’s operations cycle. Secondly, ongoing rapid transition of autonomy into warfighting capabilities is vital if the U.S. is to sustain military advantage.” — DSB Summer Study on Autonomy, June 2016 (p. 3)

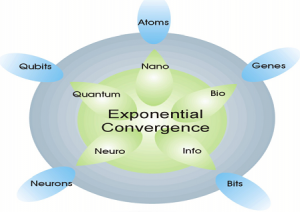

“… the study concluded that autonomy will deliver substantial operational value across an increasingly diverse array of DoD missions, but the DoD must move more rapidly to realize this value. Allies and adversaries alike also have access to rapid technological advances occurring globally. In short, speed matters—in two distinct dimensions. First, autonomy can increase decision speed, enabling the U.S. to act inside an adversary’s operations cycle. Secondly, ongoing rapid transition of autonomy into warfighting capabilities is vital if the U.S. is to sustain military advantage.” — DSB Summer Study on Autonomy, June 2016 (p. 3) Scope. It may be necessary to increase not only the pace but also the scope of these decisions if these technologies generate the “extreme future” characterized by Mad Scientist Dr. James Canton as “hacking life” / “hacking matter” / “hacking the planet.” In short, no aspect of our current existence will remain untouched. Robotics, artificial intelligence, and autonomy – far from narrow topics – are closely linked to a broad range of enabling / adjunct technologies identified by Mad Scientists, to include:

Scope. It may be necessary to increase not only the pace but also the scope of these decisions if these technologies generate the “extreme future” characterized by Mad Scientist Dr. James Canton as “hacking life” / “hacking matter” / “hacking the planet.” In short, no aspect of our current existence will remain untouched. Robotics, artificial intelligence, and autonomy – far from narrow topics – are closely linked to a broad range of enabling / adjunct technologies identified by Mad Scientists, to include:

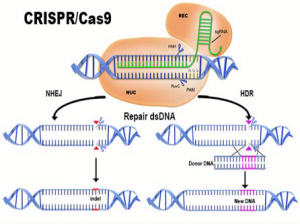

Co-Evolution. Clearly humans and these technologies are destined to co-evolve. Humans will be augmented in many ways: physically, via exoskeletons; perceptionally, via direct sensor inputs; genetically, via AI-enabled gene-editing technologies such as CRISPR; and cognitively via AI “COGs” and “Cogni-ceuticals.”

Co-Evolution. Clearly humans and these technologies are destined to co-evolve. Humans will be augmented in many ways: physically, via exoskeletons; perceptionally, via direct sensor inputs; genetically, via AI-enabled gene-editing technologies such as CRISPR; and cognitively via AI “COGs” and “Cogni-ceuticals.”  Human reality will be a “blended” one in which physical and digital environments, media and interactions are woven together in a seamless integration of the virtual and the physical. As daunting – and worrisome – as these technological developments might seem, there will be an equally daunting challenge in the co-evolution between man and machine: the co-evolution of trust.

Human reality will be a “blended” one in which physical and digital environments, media and interactions are woven together in a seamless integration of the virtual and the physical. As daunting – and worrisome – as these technological developments might seem, there will be an equally daunting challenge in the co-evolution between man and machine: the co-evolution of trust. Trusted man-machine collaboration will require validation of system competence, a process that will take our legacy test and verification procedures far beyond their current limitations. Humans will expect autonomy to be nonetheless “directable,” and will expect autonomous systems to be able to explain the logic for their behavior, regardless of the complexity of the deep neural networks that motivate it. These technologies in turn must be able to adapt to user abilities and preferences, and attain some level of human awareness (e.g., cognitive, physiological, emotional state, situational knowledge, intent recognition).

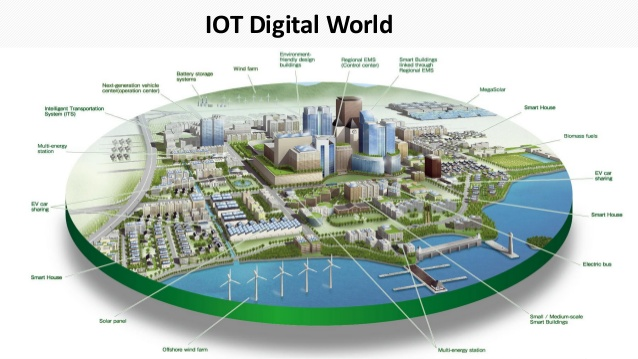

Trusted man-machine collaboration will require validation of system competence, a process that will take our legacy test and verification procedures far beyond their current limitations. Humans will expect autonomy to be nonetheless “directable,” and will expect autonomous systems to be able to explain the logic for their behavior, regardless of the complexity of the deep neural networks that motivate it. These technologies in turn must be able to adapt to user abilities and preferences, and attain some level of human awareness (e.g., cognitive, physiological, emotional state, situational knowledge, intent recognition).  Even today, unmanned combat systems can be controlled from home installations — a trend that only will increase in the future. Technological integration and advancement of future bases — artificial intelligence, big data, IoT, power generation — will also present tremendous opportunities in areas such as manufacturing, power grids, maintenance, expeditionary capability, and quality of life.

Even today, unmanned combat systems can be controlled from home installations — a trend that only will increase in the future. Technological integration and advancement of future bases — artificial intelligence, big data, IoT, power generation — will also present tremendous opportunities in areas such as manufacturing, power grids, maintenance, expeditionary capability, and quality of life.

This comes down to whether we want to be an organization like Netflix — embracing the digital revolution to create a new business model and transforming the way consumers obtain video content (away from legacy video box stores, initially to DVDs ordered on-line and received via the U.S. Postal Service, then to streaming original content on-demand); or like Kodak — developing a digital camera in 1975, but dropping it out of fear that it threatened their then lucrative analog film business, thereby missing the digital media wave that would forever change their business model.

This comes down to whether we want to be an organization like Netflix — embracing the digital revolution to create a new business model and transforming the way consumers obtain video content (away from legacy video box stores, initially to DVDs ordered on-line and received via the U.S. Postal Service, then to streaming original content on-demand); or like Kodak — developing a digital camera in 1975, but dropping it out of fear that it threatened their then lucrative analog film business, thereby missing the digital media wave that would forever change their business model. Netflix was future ready, while Kodak writhed in bankruptcy and suffered a slow, painful decline.

Netflix was future ready, while Kodak writhed in bankruptcy and suffered a slow, painful decline. • How does our organization transform to face challenges or opportunities in a rapidly evolving operational environment?

• How does our organization transform to face challenges or opportunities in a rapidly evolving operational environment? • How does our organization build, retain, and regain decisive advantage in relation to our competitors?

• How does our organization build, retain, and regain decisive advantage in relation to our competitors? • How does our organization develop the ability to quickly adapt to emerging trends and traditional and non-traditional competitors’ actions?

• How does our organization develop the ability to quickly adapt to emerging trends and traditional and non-traditional competitors’ actions?

In addition to having a wide aperture looking across timeframes by tapping into all available networks and by establishing and mobilizing search parties, such as the Mad Scientist initiative [Day and Schoemaker used the analogy of a “crow’s nest”], we must be (1) open minded; (2) take a deep dive on the most worrisome findings through such techniques as red vs. blue analysis, and (3) maintain an inherent red teaming process throughout the effort to challenge the finding, insight, observation or recommendation for action.5

In addition to having a wide aperture looking across timeframes by tapping into all available networks and by establishing and mobilizing search parties, such as the Mad Scientist initiative [Day and Schoemaker used the analogy of a “crow’s nest”], we must be (1) open minded; (2) take a deep dive on the most worrisome findings through such techniques as red vs. blue analysis, and (3) maintain an inherent red teaming process throughout the effort to challenge the finding, insight, observation or recommendation for action.5 Surprises will happen, especially in the technology arena. The creation of new knowledge is not confined to the U.S. given the globalization of technology. As the Defense Science Board noted in 2009 – having the ability to make “really bad things happen” is no longer the sole province of a few major states. Yet, as we often focus on “game changing” or “disruptive future technologies,” Dr. Paul Bracken of Yale University reminds us that old technology used differently or a combination of old technologies combined can be just as dangerous as new technologies.

Surprises will happen, especially in the technology arena. The creation of new knowledge is not confined to the U.S. given the globalization of technology. As the Defense Science Board noted in 2009 – having the ability to make “really bad things happen” is no longer the sole province of a few major states. Yet, as we often focus on “game changing” or “disruptive future technologies,” Dr. Paul Bracken of Yale University reminds us that old technology used differently or a combination of old technologies combined can be just as dangerous as new technologies.

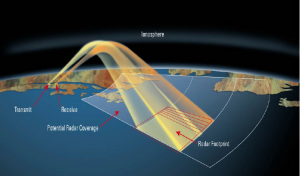

In essence, sidewise technologies are those which combine technologies – such as missiles and Over-the-Horizon radar – to present new challenges and dangers. Even simple technologies such as those used for the IEDs of the past, current and future will challenge us, as will commercial and military unmanned systems of all types.

In essence, sidewise technologies are those which combine technologies – such as missiles and Over-the-Horizon radar – to present new challenges and dangers. Even simple technologies such as those used for the IEDs of the past, current and future will challenge us, as will commercial and military unmanned systems of all types.  We must be mindful of the cognitive diseases that affect our assessments about the future by being both humble and skeptical. As Yoda, the wise Jedi master in Star Wars noted – “Difficult to see, always in motion is the future.”

We must be mindful of the cognitive diseases that affect our assessments about the future by being both humble and skeptical. As Yoda, the wise Jedi master in Star Wars noted – “Difficult to see, always in motion is the future.” The Bottom line: Assessing the future is critical to remaining competitive, whether in the boardroom or battlefield. As Yogi said – “The future isn’t what it used to be.”

The Bottom line: Assessing the future is critical to remaining competitive, whether in the boardroom or battlefield. As Yogi said – “The future isn’t what it used to be.”