[Editor’s Note: The Army’s Mad Scientist Laboratory is pleased to feature the next in a series of posts excerpting findings from Team Axis Insight 2035‘s Project Deterrence Final Report. This Integrated Research Project documents the findings from the group’s United States Army War College (USAWC) Strategic Research Requirement portion of the Master of Strategic Studies degree program that occurred over the academic year (from November 2024 to April 2025).

Team Axis Insight 2035 consisted of COL Byron N. Cadiz, COL T. Marc Skinner, LTC Robert W. Mayhue, LTC Lori L. Perkins, and LTC Shun Y. Yu — all U.S. Army Officers and now proclaimed Army Mad Scientists! Team Axis Insight 2035‘s Project Deterrence Final Report documents their collective response to the following question posed by Ian Sullivan, Deputy Chief of Staff, G-2, U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command:

How are China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea likely to respond to U.S.-led deterrence efforts by 2035?

To date, the Mad Scientist Laboratory has excerpted Team Axis Insight 2035‘s findings regarding “an entangled future of situational cooperation and transactional inter-dependence among China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea” in Project Deterrence — An Entangled Future; how our adversaries are likely to integrate “four future capabilities … to create an environment where U.S. deterrence is neutralized: quantum warfare, swarm supremacy, hypersonic strike, and metamaterials” in Project Deterrence – Disruptive Technologies; and how our adversaries are employing gray zone activities to “saturate the competition continuum below the level of armed conflict” and achieve a state of persistent coercion in Project Deterrence – Persistent Coercion.

In today’s post, we excerpt COL Byron Cadiz‘s submission exploring how China is challenging the United States’ dominance in the Space domain — along with a specific use case addressing the operational impacts of ceding the Space Domain’s high ground to our sole pacing threat — Read on!]

Executive Summary

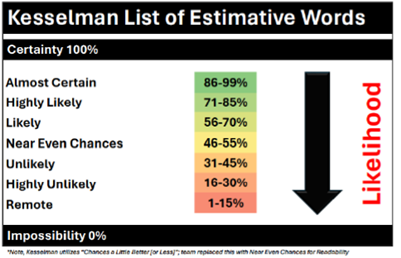

China is highly likely* (71–85%) to overtake the U.S. in space dominance by 2035. China’s rapid advancements in space, driven by centralized planning, military-civil fusion, and international partnerships, position it to challenge U.S. dominance in the coming decades. With milestones like the Chang’e-6 lunar mission and plans for a crewed Moon landing by 2030, China is avoiding the delays that have plagued U.S. programs like Artemis. Its satellite mega-constellations and counter-space capabilities threaten U.S. military operations reliant on space-based systems, while partnerships through initiatives like the International Lunar Research Station expand its global influence. If China surpasses the U.S. in space dominance, adversaries such as Russia, Iran, and North Korea could exploit weakened American deterrence and rely on Chinese infrastructure to pursue more aggressive strategies. This shift would have profound implications for global security and power dynamics in the 21st century.

China is highly likely* (71–85%) to overtake the U.S. in space dominance by 2035. China’s rapid advancements in space, driven by centralized planning, military-civil fusion, and international partnerships, position it to challenge U.S. dominance in the coming decades. With milestones like the Chang’e-6 lunar mission and plans for a crewed Moon landing by 2030, China is avoiding the delays that have plagued U.S. programs like Artemis. Its satellite mega-constellations and counter-space capabilities threaten U.S. military operations reliant on space-based systems, while partnerships through initiatives like the International Lunar Research Station expand its global influence. If China surpasses the U.S. in space dominance, adversaries such as Russia, Iran, and North Korea could exploit weakened American deterrence and rely on Chinese infrastructure to pursue more aggressive strategies. This shift would have profound implications for global security and power dynamics in the 21st century.

Discussion

The 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) prioritizes lunar exploration, with the Chang’e-6 mission marking the first-ever sample return from the Moon’s far side, a feat the U.S. has yet to attempt. Meanwhile, NASA’s Artemis III crewed lunar landing faces delays to 2026 due to technical and budgetary hurdles, while China aims to land astronauts on the Moon by 2030 and establish a permanent research base by 2035. This centralized model allows China to avoid the legislative gridlock and shifting priorities that hamper U.S. programs, ensuring sustained funding and political backing for its space agenda.

The 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) prioritizes lunar exploration, with the Chang’e-6 mission marking the first-ever sample return from the Moon’s far side, a feat the U.S. has yet to attempt. Meanwhile, NASA’s Artemis III crewed lunar landing faces delays to 2026 due to technical and budgetary hurdles, while China aims to land astronauts on the Moon by 2030 and establish a permanent research base by 2035. This centralized model allows China to avoid the legislative gridlock and shifting priorities that hamper U.S. programs, ensuring sustained funding and political backing for its space agenda.

China’s military space capabilities have been consolidated in the PLA’s Aerospace Force — established on 19 April 2024 and severed from the simultaneously dis-established People’s Liberation Army Strategic Support Force (PLASSF) — to accelerate innovation. Projects like the Yangwang-1 satellite, which employs quantum communications for both civilian internet and secure military networks — exemplify civilian and military space synergy. Private firms like GalaxySpace and LandSpace collaborate closely with state agencies to develop reusable rockets and satellite constellations, mirroring SpaceX’s success but with direct government coordination. In contrast, U.S. military-commercial partnerships remain hindered by bureaucratic barriers and export controls, limiting agility in deploying dual-use technologies.

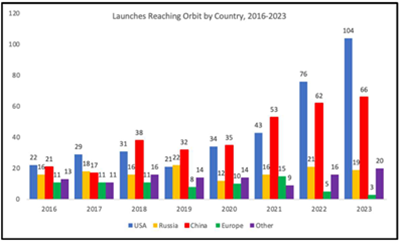

China’s GuoWang constellation, set to deploy 13,000 satellites by 2030, aims to rival SpaceX’s Starlink while expanding surveillance and global internet coverage (see figure below)

This initiative complements the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), where satellites provide Earth observation and communications services to partner nations, embedding Chinese technology into global infrastructure. Meanwhile, U.S. reliance on private firms risks fragmentation: SpaceX’s dominance in launch services (80% of global commercial launches in 2024) has stifled competition, leaving critical infrastructure vulnerable to corporate priorities.

China’s International Lunar Research Station, developed with Russia and seven Global South nations, offers an alternative to the U.S.-led Artemis Accords. This coalition enables resource-sharing and diplomatic influence, particularly in Africa and Southeast Asia, where China has pledged to fund spaceports and training programs. Militarily, China’s advancements in ground-based lasers and satellite jammers threaten U.S. GPS and reconnaissance networks, eroding America’s asymmetric space dominance. Despite the U.S. leading in deep-space exploration, China’s focus on pragmatic, dual-use systems, coupled with its $150 billion investment in semiconductor self-reliance, positions it to dominate near-Earth orbit and lunar infrastructure, key battlegrounds for 21st-century space power.

China’s International Lunar Research Station, developed with Russia and seven Global South nations, offers an alternative to the U.S.-led Artemis Accords. This coalition enables resource-sharing and diplomatic influence, particularly in Africa and Southeast Asia, where China has pledged to fund spaceports and training programs. Militarily, China’s advancements in ground-based lasers and satellite jammers threaten U.S. GPS and reconnaissance networks, eroding America’s asymmetric space dominance. Despite the U.S. leading in deep-space exploration, China’s focus on pragmatic, dual-use systems, coupled with its $150 billion investment in semiconductor self-reliance, positions it to dominate near-Earth orbit and lunar infrastructure, key battlegrounds for 21st-century space power.

China surpassing the U.S. in space dominance could significantly weaken American and allied deterrence, indirectly benefiting adversaries such as Russia, Iran, and North Korea. Dominance in space, essential for intelligence, precision targeting, and secure communications, could enable China to disrupt U.S. satellite networks using advanced anti-satellite, cyber, and electronic warfare capabilities. Consequently, the U.S. could face reduced capacity to monitor adversarial actions or respond swiftly and effectively. Additionally, a China-led space infrastructure could provide strategic rivals with resilient alternatives to Western-dependent systems like GPS. This shift could embolden these nations to adopt more aggressive postures, recognizing diminished U.S. influence and capability in space.

Analytic Confidence

The analytic confidence for this assessment is moderate, supported by substantial corroboration across a diverse range of credible U.S. and Chinese sources. A comprehensive global search strategy, utilizing advanced Google techniques, was employed to identify relevant materials, ensuring a wide scope of data collection. ChatGPT was leveraged to refine grammar and sentence structure for clarity and professionalism. However, the analysis was conducted by a single analyst without the application of a structured methodological framework, which may limit the rigor of the findings. Additionally, given the extended timeframe of this assessment, the conclusions remain subject to potential revisions as new information becomes available.

A Use Case: Space Blitzkrieg by 2035 – China Highly Likely to Use ASAT Weapons to Blind U.S. and Allies During Taiwan Invasion

Executive Summary

China is highly likely* (71–85%) to use anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons during an invasion of Taiwan by 2035. China is expected to possess ASAT capabilities that can threaten satellites in all orbital regimes, from low Earth orbit to geosynchronous orbit, significantly expanding its strategic reach. The PLA views space dominance as critical for modern warfare and has integrated counterspace operations into its military doctrine, indicating a readiness to employ these capabilities when deemed necessary. China’s perception that space underpins U.S. military superiority makes American space assets an attractive target, potentially leading to their use in a conflict scenario.

China is highly likely* (71–85%) to use anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons during an invasion of Taiwan by 2035. China is expected to possess ASAT capabilities that can threaten satellites in all orbital regimes, from low Earth orbit to geosynchronous orbit, significantly expanding its strategic reach. The PLA views space dominance as critical for modern warfare and has integrated counterspace operations into its military doctrine, indicating a readiness to employ these capabilities when deemed necessary. China’s perception that space underpins U.S. military superiority makes American space assets an attractive target, potentially leading to their use in a conflict scenario.

Discussion

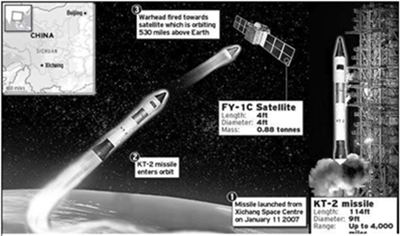

The PLA views counterspace operations as a crucial means to deter and counter U.S. military intervention in regional conflicts, particularly regarding Taiwan. This belief is evidenced by China’s significant investments in a range of ASAT technologies (See figure below), including kinetic-kill vehicles, directed-energy weapons, and cyber capabilities.

Recent intelligence suggests that China has been rapidly expanding its military space capabilities, launching numerous satellites designed for long-range precision strikes against U.S. and allied forces. This expansion aligns with China’s designation of space as a new domain of warfare in 2015 and the subsequent reorganization of its military space capabilities. The PLA’s active training on operational ground-based ASAT systems further indicates its readiness to employ these weapons in a conflict scenario.

Furthermore, China’s growing risk tolerance in space, suggests that they are highly likely to use ASAT weapons in pursuit of its strategic goals. This shift in thinking emphasizes a more proactive approach to shaping the international environment, even at the cost of potential escalation with the United States. The PLA’s evolving doctrine of “active defense” in space operations (their foundational concept for space operations can be thought of as a shield of clever attacks; it is a defense whose goals are passive but whose means are active) further supports this assessment, advocating for offensive actions within a broader defensive strategy.

Furthermore, China’s growing risk tolerance in space, suggests that they are highly likely to use ASAT weapons in pursuit of its strategic goals. This shift in thinking emphasizes a more proactive approach to shaping the international environment, even at the cost of potential escalation with the United States. The PLA’s evolving doctrine of “active defense” in space operations (their foundational concept for space operations can be thought of as a shield of clever attacks; it is a defense whose goals are passive but whose means are active) further supports this assessment, advocating for offensive actions within a broader defensive strategy.

Despite the potential for creating dangerous space debris, which could harm their own satellites and draw international condemnation, China’s growing risk tolerance in space and its view of space deterrence as a means to coerce adversaries into submission to Beijing’s political objectives suggest an increased willingness to utilize ASAT weapons in pursuit of its strategic goals.

Despite the potential for creating dangerous space debris, which could harm their own satellites and draw international condemnation, China’s growing risk tolerance in space and its view of space deterrence as a means to coerce adversaries into submission to Beijing’s political objectives suggest an increased willingness to utilize ASAT weapons in pursuit of its strategic goals.

In the context of a Taiwan invasion, China is highly likely to use ASAT weapons to blind U.S. military satellites and disrupt communication systems critical for coordinating a response. The reported development of AI-powered disruption techniques targeting satellite constellations like Starlink demonstrates China’s preparation for such a scenario. By employing ASAT weapons, China aims to gain space superiority, a crucial element in its strategy to prevent external intervention and secure a swift victory in a potential Taiwan conflict.

Analytic Confidence

The analytic confidence for this estimate is high. The multiple sources used were moderate to highly reliable and largely corroborated each other. ChatGPT was used to refine grammar and sentence structure. Despite ample time for analysis, a single analyst conducted the work without a structured methodology. Moreover, due to the protracted timeframe of this estimate, the findings remain vulnerable to revisions as new information emerges.

* Kesselman List of Estimative Words:

If you enjoyed this post, check out Axis Insight 2035‘s comprehensive Project Deterrence Final Report here, as well as each of the previously excerpted and published blog posts:

Project Deterrence – An Entangled Future

Project Deterrence – Disruptive Technologies

Project Deterrence – Persistent Coercion

Review the TRADOC Pamphlet 525-92, The Operational Environment 2024-2034: Large-Scale Combat Operations

Explore the TRADOC G-2‘s Operational Environment Enterprise web page, brimming with authoritative information on the Operational Environment and how our adversaries fight, including:

Our China Landing Zone, full of information regarding our pacing challenge, including ATP 7-100.3, Chinese Tactics, How China Fights in Large-Scale Combat Operations, BiteSize China weekly topics, and the People’s Liberation Army Ground Forces Quick Reference Guide.

Our Russia Landing Zone, including the BiteSize Russia weekly topics. If you have a CAC, you’ll be especially interested in reviewing our weekly RUS-UKR Conflict Running Estimates and associated Narratives, capturing what we learned about the contemporary Russian way of war in Ukraine over the past two years and the ramifications for U.S. Army modernization across DOTMLPF-P.

Our Iran Landing Zone, including the Iran Quick Reference Guide and the Iran Passive Defense Manual (both require a CAC to access).

Our North Korea Landing Zone, including Resources for Studying North Korea, Instruments of Chinese Military Influence in North Korea, and Instruments of Russian Military Influence in North Korea.

Our Irregular Threats Landing Zone, including TC 7-100.3, Irregular Opposing Forces, and ATP 3-37.2, Antiterrorism (requires a CAC to access).

Our Running Estimates SharePoint site (also requires a CAC to access) — documenting what we’re learning about the evolving OE. Contains our monthly OE Running Estimates, associated Narratives, and the quarterly OE Assessment TRADOC Intelligence Posts (TIPs).

Then read the following related Mad Scientist Laboratory space domain content:

African Skies: Space Exploration and National Security Perspectives and associated podcast, with Selina Hayes

Building Beyond: Preparing the Army for Lift-Off and associated podcast, with Dr. Olga Bannova

LSCO, PNT, and the Space Domain, by CPT Matthew R. Bigelow

Space: Challenges and Opportunities

Star Wars 2050, The Final Frontier: Directed Energy Applications in Outer Space, and The Evolution of Nation-States and Their Role in the Future, by proclaimed Mad Scientist Marie Murphy

Beyond Space and associated podcast, with proclaimed Mad Scientist Kara Cunzeman

Space 2035: A Surplus of Uncertainty and a Deficit of Trust, by Maj Rachel Reynolds

Accelerating American Space Settlements, by Dr. Lydia Kostopoulos

Table of Future Technologies: A 360 Degree View Based on Anticipated Availability, by Richard Buchter

… then listen to a podcast with Dr. Moriba Jah on What Does the Future Hold for the US Military in Space? — hosted by our colleagues at Modern War Institute.

About the Author: Byron Cadiz is a Colonel in the U.S. Army National Guard and recent graduate of the Army War College. He previously served as the State Army Aviation Officer for the Hawaii Army National Guard, and has commanded the 103rd Troop Command and Company B, 1st Battalion, 171st Aviation Regiment. He has also participated in international exercises like Gema Bhakti with the Tentara Nasional Indonesia (Indonesian National Armed Forces).

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).