[Editor’s Note: Army Mad Scientist welcomes returning guest blogger LTC Nathan Colvin with today’s insightful post exploring how game theory can help us understand our adversaries’ motivations. Using contemporary Russia as a use case, LTC Colvin explores the dynamics affecting three principal “actors” – the transnational “liberal order” (i.e., the West), the diffuse aggregate needs of the Russian people (a society of individuals), and the individual needs of Russia’s President Vladimir Putin himself (as an autocratic leader) — to clinically explain the rationale underlying the superficially irrational invasion of Ukraine. LTC Colvin’s innovative integration of gaming theories provides us with an additional tool to understand (and predict) our adversaries’ behaviors across the spectrum of competition, crisis, and conflict — Read on!]

It almost goes without saying that war is an intimately human endeavor. The human costs of war bring justifiable emotional turmoil, angst, and shock. Especially in the western world, war thrusts millions into the position of trying to make sense of it. In Russia’s renewed invasion of Ukraine, so much of the sense-making revolves around the narrative of irrationality. People ask, “In modern Europe, what sort of madman makes this possible?” It simply does not make sense in the value system of the West. The only answer must be that the actors causing this pain are mad, insane, or irrational.

While explanations like these may provide emotional refuge, they simply aren’t true. In fact, our adversaries continue to demonstrate their rationality on a daily basis. First, I would offer that when we confuse immorality with irrationality, the issue begins. Among several definitions, rationality can be thought of the logic of achieving one’s goals, whatever those goals might be. At its roots, rationality is about ratios, the weighing of outcomes or chances against each other. In other words, to understand how the world is, the values of the actor are paramount, not whether those values are compatible with our own.

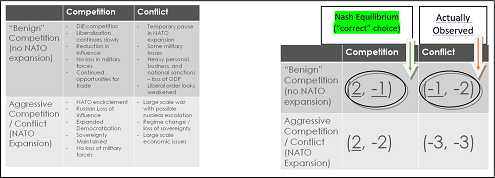

In the summer of 2021, I tested this idea for a Game Theory course I took towards my PhD. The dominate narrative in the media claimed that Vladimir Putin was at best an opportunist, not a strategist. I set about designing a game that could either help support or refute this idea. First, I built a version of the game that reflected a traditional state-on-state interaction, typical of the Kenneth Waltz neorealist perspective of international relations. In a non-cooperative game, analysts look for the Nash Equilibrium – the point of optimal outcome for each player (indicated with green highlights in this paper). Of course, the game’s predicted

In the summer of 2021, I tested this idea for a Game Theory course I took towards my PhD. The dominate narrative in the media claimed that Vladimir Putin was at best an opportunist, not a strategist. I set about designing a game that could either help support or refute this idea. First, I built a version of the game that reflected a traditional state-on-state interaction, typical of the Kenneth Waltz neorealist perspective of international relations. In a non-cooperative game, analysts look for the Nash Equilibrium – the point of optimal outcome for each player (indicated with green highlights in this paper). Of course, the game’s predicted  behavior did not match the observed behavior of Putin’s Russia. The Nash Equilibrium indicated that Russia and the West should cooperate or conduct benign competition. But what Russia actually did was attack nations in their near abroad, despite the increasing economic and reputational cost to the country.

behavior did not match the observed behavior of Putin’s Russia. The Nash Equilibrium indicated that Russia and the West should cooperate or conduct benign competition. But what Russia actually did was attack nations in their near abroad, despite the increasing economic and reputational cost to the country.

On first glance, this seems irrational – why would Russia act against its state interests? According to game theory, the game ran as it should. However, the game did not reflect the proper actors or their motivation. When the actors were reevaluated to real world conditions rather than ideal ones, the Nash Equilibrium suddenly matched both demonstrated and future behaviors. In the second game, I took a different approach. In a nod to Robert Putnam’s theory of international negotiation, I put the focus on Putin as decision maker, between an external western liberal order and the Russian domestic audience. Putin was treated as a unitary autocratic decision maker, in a three player game. By evidence of the outcome and current events, the results of this game were not only explanatory, but to a degree, predictive.

Major findings were that Putin benefited the most when choosing violence over peacemaking, that he would continuously de-liberalize internally, the West would not intervene militarily, but Article 5 of the NATO Treaty would be effective as a deterrent to an attack on a member.

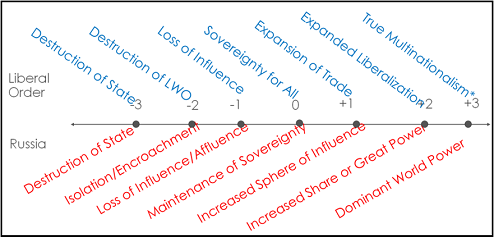

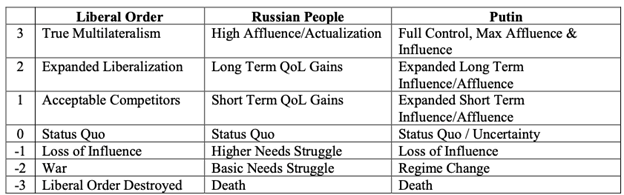

Design of both games started with Graham Allison’s Rational Choice Theory. Using Allison’s ideas for a non-cooperative game meant first understanding the relevant actors, their goals’ relative ranking, consideration of their options, assessment of the consequences of choices, and utility maximization. Rational Choice Theory traditionally relies on states as actors, as I used in the first game. In the second game, it was necessary to look at the specific goals and utility to different types of actors – the transnational “liberal order” (group of states), the diffuse aggregate needs of the Russian people (a society of individuals), and finally the individual needs of Putin himself (a single person). Using a constructivist approach, I incorporated a number of perspectives in liberal political theory, historical observation, and individual psychology — including the ever-present Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. The result was the ability to compare three very different value systems, inside of one game.

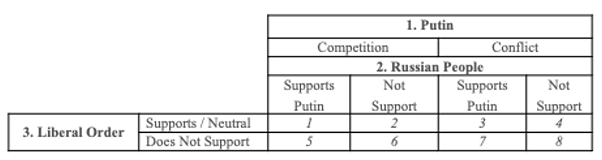

When arranging the goals and possible outcomes for these disparate actors, eight possible worlds were created. Although not technically necessary, short narratives of these worlds were created to help recognize them in a qualitative evaluation against recent events. When looking at the narrative alone, it is easy to see where biases such as mirror-imaging can come into play. If someone were to look at the list of worlds, it would be tempting to pick the one that looks the best for everyone. But that is not how non-cooperative games work. Instead each actor seeks their best outcomes. While not necessarily zero-sum (I win – you lose), the players are agnostic to the benefits to the other players. Below is a short description of the eight worlds.

-

- “Globalization Glasnost” – President Putin chooses relatively benign competition, the Russian people support him, and the liberal order also chooses a form of benign competition.

- “Internal Entropy” – In this scenario, President Putin chooses relatively benign competition, the Russian people do not support him, but the liberal order does not take active involvement.

- “Rapid Expansion” – In this configuration, President Putin chooses regional conflict, the Russian people support this decision, and the liberal order does nothing significant to halt this activity.

- “Regional Chaos” – This case sees President Putin choosing conflict, while the Russian people do not support this activity, but the liberal order does not intercede in either the external or internal conflict.

- “Cold Shoulder” – Here, President Putin chooses benign competition instead of armed conflict in an attempt to repair relations, the Russian people support this move of reconciliation, but the liberal order’s reaction is lukewarm at best.

- “Everyone is Against Me” – When President Putin chooses benign competition, the Russian people cannot understand the sudden reversal and do not support it.

- “Underdog Victory” – In this scenario, President Putin is bolstered by the success of incremental increases in regional conflicts and the Russian people support him, but the liberal order pushes back.

- “Doomsday” – In this final scenario, President Putin chooses conflict and this leads to escalation to large-scale conflict with the liberal order.

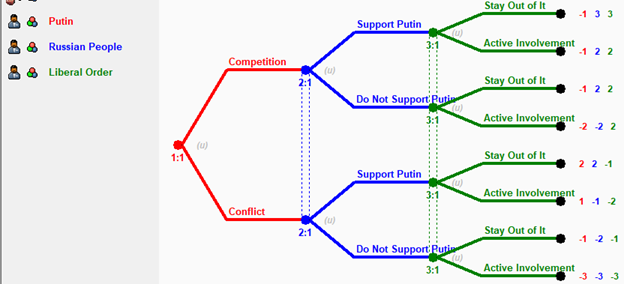

A decision tree provides a usable framework to evaluate the combination of choices and their utility to each actor/player. This structure helps separate analysts from relying on heuristics, bias, or intuition. Using this adapted rational choice theory and non-cooperative game theory, actors do not seek outcomes that are best for everyone, but what are best for themselves.

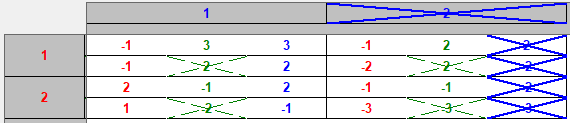

The game works like this. Each player is making its decisions based on their specific goals as outlined in the Layout of Worlds table (above). The game is simultaneous, meaning each player evaluates their options based on their understanding of the other player’s goals, and the utility or value of those actions to themselves. But which decision is best? To determine the most rational choice, we look for the dominant choice amongst each option, through a process known as iterated dominance. The first actor to examine is Putin.

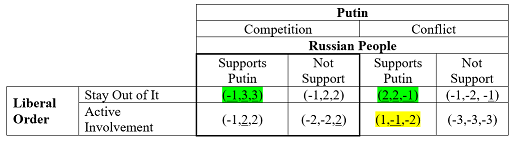

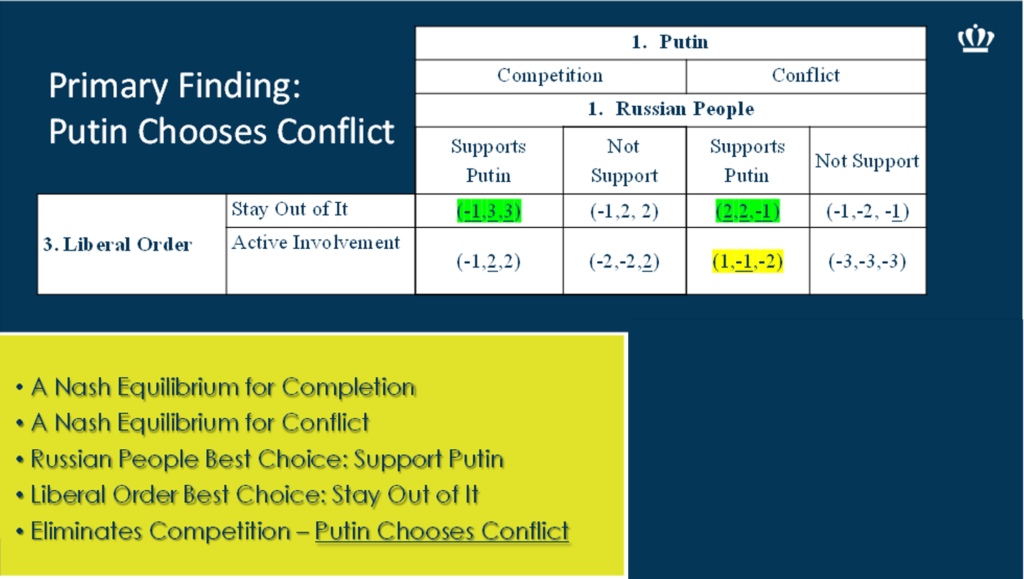

Putin’s decision lies between benign competition or attacking. In the long run, if he chooses benign competition, his power base slowly erodes as globalization creates greater liberalization in Russia, eventually requiring leaving the seat of power. If this occurs, there is no guarantee of his personal safety or reputation remaining intact. Likely, his years of political engineering requires an all or nothing approach to power. Therefore, despite conflict having negative impacts to the Russian state, Putin sees clear advantages to remaining in power where he can continue to survive, and possibly even shape a continuing historical legacy for himself. By examining his choice between competition and conflict separately, two Nash Equilibriums highlight his payoffs. Evaluating his options, he sees that competition/cooperation with the West lead to negative (-1) personal outcomes, while conflict leads to positive (+2) personal benefits.

Putin’s decision lies between benign competition or attacking. In the long run, if he chooses benign competition, his power base slowly erodes as globalization creates greater liberalization in Russia, eventually requiring leaving the seat of power. If this occurs, there is no guarantee of his personal safety or reputation remaining intact. Likely, his years of political engineering requires an all or nothing approach to power. Therefore, despite conflict having negative impacts to the Russian state, Putin sees clear advantages to remaining in power where he can continue to survive, and possibly even shape a continuing historical legacy for himself. By examining his choice between competition and conflict separately, two Nash Equilibriums highlight his payoffs. Evaluating his options, he sees that competition/cooperation with the West lead to negative (-1) personal outcomes, while conflict leads to positive (+2) personal benefits.

Based on the goals in the Actors’ Goals table (above), the Russian people are better off supporting Putin. This might seem counter-intuitive, since war could have serious economic and physical consequences to the population. However, the likely consequence of war are unevenly distributed – not everyone will be drafted, or face shelling, etc. However, resisting the regime is nearly guaranteed to result in negative consequences such as jail, involuntary service, or other negative impacts. The range of outcomes for supporting Putin is +3 to -2, while non-supporting ranges from +2 to -3. Therefore, the option for the Russian population to resist is nearly immediately eliminated.

Similarly, the West reduces its risk (using the goals defined above) by not directly participating in combat operations. Instead is seeks various ways to compete indirectly, such as security assistance, sanctions, and other deterrent actions. The outcomes for the West to stay out of conflict range from +3 to -1, while directly engaging in conflict with Russia range from +2 to -3.

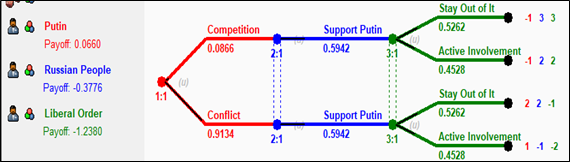

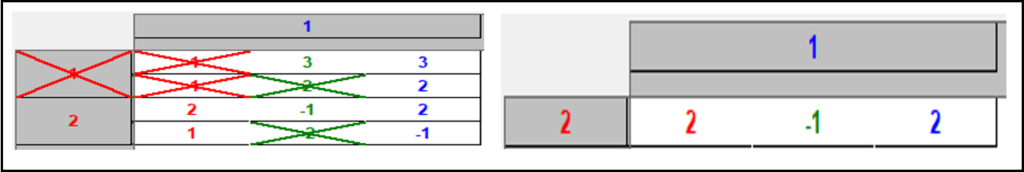

As the Russian people and the West remove the choices most dangerous to them, they also remove some of the highest risks to Putin as well. While many might advocate for the toughest possible response, realistically, global thermonuclear war will benefit no one. However, when these higher consequences are taken off the table, Putin is emboldened by the lack of either foreign or domestic resistance. There is no longer any counterweight to some of his most aggressive choices, as seen below.

In fact, through the continued application of iterated dominance, there is really only one rational choice. This is where Putin chooses conflict, the Russian people support him (at least passively), and the western liberal order does not go to war. These results are only possible because of the values assigned through careful scoping of the actors and study of their likely goals.

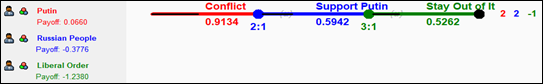

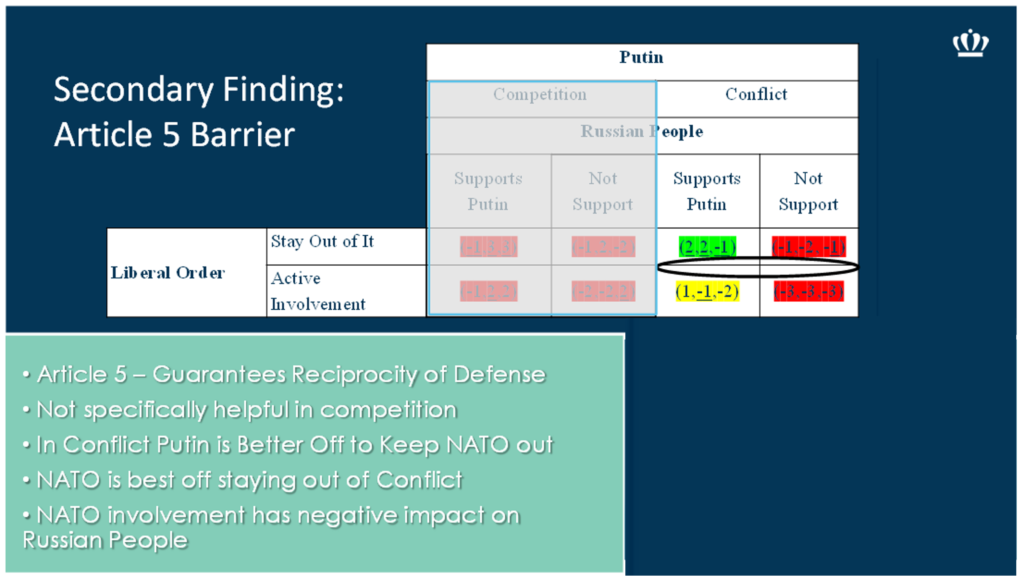

If there is good news from this game, it is that Article Five of the NATO treaty can be an effective deterrent to conflict that is compatible with the demonstrated behaviors of our actors. Looking at the game scoring there are advantages to Putin and the western liberal order avoiding direct conflict with each other. For example, Putin has choices of 2 (with domestic support) and -1 (without it), if the West does not fight him compared to 1 (with domestic support) and -3 (without it) if the West does fight him. Similarly, it is in the best interests of the Russian people for their country not to attack NATO. From an information warfare perspective, calls to attack NATO or “drive to Berlin” could be signs of splintering between Putin and ultra-nationalists in Russia, who are driven by another set of goals not evaluated in this game. To a degree, Putin’s team will use these narratives to support the idea they are the aggrieved party, or even as a signal to the West that they should not intercede with direct military force. However, the official party line should not support the idea of Russia going on the offensive against NATO. If that occurs, a new game is forming with additional dominant players.

If there is good news from this game, it is that Article Five of the NATO treaty can be an effective deterrent to conflict that is compatible with the demonstrated behaviors of our actors. Looking at the game scoring there are advantages to Putin and the western liberal order avoiding direct conflict with each other. For example, Putin has choices of 2 (with domestic support) and -1 (without it), if the West does not fight him compared to 1 (with domestic support) and -3 (without it) if the West does fight him. Similarly, it is in the best interests of the Russian people for their country not to attack NATO. From an information warfare perspective, calls to attack NATO or “drive to Berlin” could be signs of splintering between Putin and ultra-nationalists in Russia, who are driven by another set of goals not evaluated in this game. To a degree, Putin’s team will use these narratives to support the idea they are the aggrieved party, or even as a signal to the West that they should not intercede with direct military force. However, the official party line should not support the idea of Russia going on the offensive against NATO. If that occurs, a new game is forming with additional dominant players.

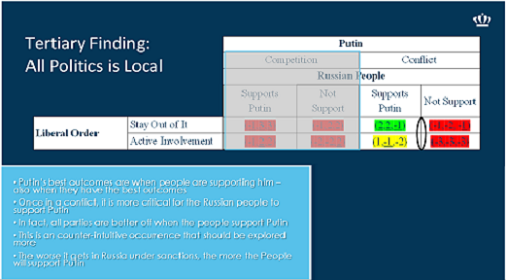

Another phenomenon that is visualized in the results is the dominance of the domestic audience to Putin, even when foreign affairs are the main topic. Especially in modern times, far more rulers leave their offices due to the will of the people rather than foreign intervention. For the autocrat who ruthlessly wields power, enemies accrue over time. Staying in the seat of power becomes a survival strategy, not just a vanity project. Maintaining domestic support is one of the largest components to high payoffs for Putin. This idea circles back to the writing of Robert Putnam who demonstrated that in two-level games, any negation with external parties must have at least tacit agreement of the internal audience.

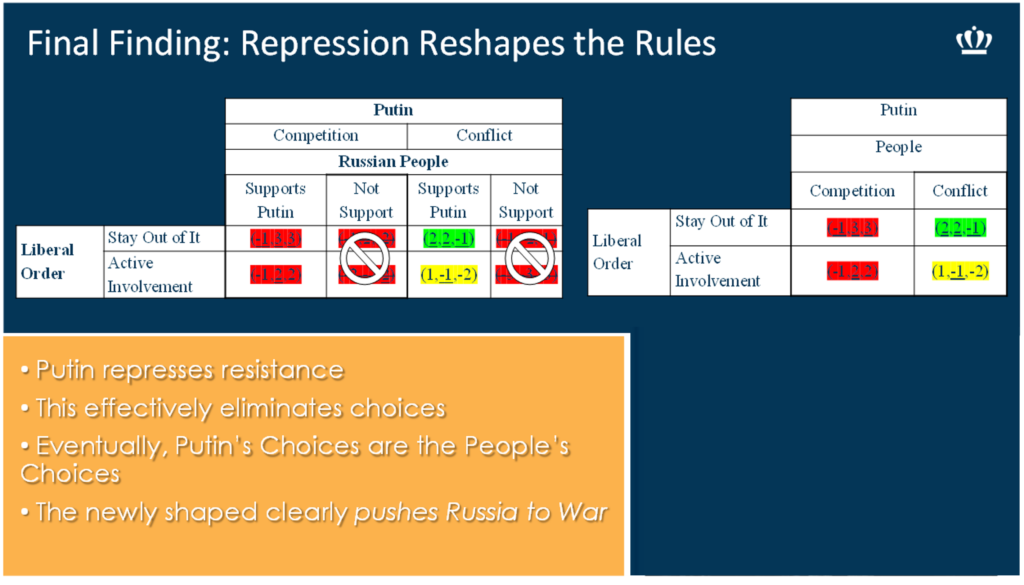

Controlling most levers for the use of force, autocrats are capable of actively reshaping the game. By repression of the media, assembly, and other forms of domestic resistance, authoritarian regimes (including autocrats) remove domestic audience choice from the playing table. Once a domestic audience is basically compliant, the autocrat’s decisions are the people’s decisions. This speeds decision making for the regime; however the system’s resiliency is then tied to the benevolence of the autocrat. Unfortunately, in both history and psychology, the more means at the disposal of an actor, the more likely they will use that power for their own purposes. For the autocratic actor, power and control are signals to reinforce their behavior; success should begat more success after all. This leads to more concentration of power and repression until such point that the domestic audience is compelled to act. Perhaps this is why so many rulers cannot understand the problem as they are carried to the guillotine.

As I pointed out in the introduction, many of the dominant narratives in media, think pieces, and even academia revolve around the apparent irrationality of Putin and Russia. These narratives rely on a Kantian notion of rationality, based  on what is right, ethical, and moral. While morality and ethics are critical in international decision making, they are not particularly predictive if we assume their universality. Instead, we are apt to employ a type of ethnocentrism that blinds us to the true ambition of our adversaries. As TRADOC’s The Red Team Handbook manual points out, this mirror imaging is “the expectation that others will think and act like us despite having different experiences and cultural backgrounds.” When we apply an idea of universal morality to rationality, the world seems like a much more confusing place.

on what is right, ethical, and moral. While morality and ethics are critical in international decision making, they are not particularly predictive if we assume their universality. Instead, we are apt to employ a type of ethnocentrism that blinds us to the true ambition of our adversaries. As TRADOC’s The Red Team Handbook manual points out, this mirror imaging is “the expectation that others will think and act like us despite having different experiences and cultural backgrounds.” When we apply an idea of universal morality to rationality, the world seems like a much more confusing place.

The overall lesson I took away is that if we can limit rationality not to the ideal endstate, but rather to the process of achieving goals, there is hope for rationality to both explain and provide some limited predictive power. In its purest form, rationality is about ratios, the measure of what the utility of a given choice are. By treating the “ends” as a desired state of being and the “ways” as a process of becoming, games such as these can help us methodically gain better understanding. While we may wish for universal values, most evidence supports that when power is concentrated, it is used for personal gain. While morally depressing, understanding the differences in goals allows for better analysis. This drives home the point that cultural education and red teaming skills are as, if not more important in large scale combat operations as they were during the Global War on Terror. Without these skills, it is more difficult to discern who the actors are and what their likely goals might be.

When we apply red teaming type perspectives to game theory, we see that Putin has a dramatically different worldview than the West. From that world view, however, his actions are completely rational. The autocrat’s own survival is the primary concern of international activity. This is why Russia often pursues aims that are not fully aligned with international goals of sovereignty preservation, multilateralism, and protection of borders from actual threats. For the autocrat, all politics is local, even in international politics. International activities are a means to distract from domestic issues, create external straw man threats, quell dissention, and reinforce personal power. For years Putin played a strategic game to keep himself enriched and empowered. Whether facing his own mortality, a lack of information, believing his own hype, or a host of other reasons, Putin may have bitten off more than he can chew in Ukraine. However, the fact that he acted with violence against a non-NATO country was not only rational for him, it was predicted.

If you enjoyed this post, explore the TRADOC G-2‘s Operational Environment Enterprise web page, brimming with information on the Operational Environment and our how our adversaries fight. If you have a Common Access Card, you’ll be especially interested in our weekly Russia-Ukraine Conflict Running Estimates, capturing what we are learning about the contemporary Russian way of war in Ukraine and the ramifications for U.S. Army modernization across DOTMLPF-P — access them all here…

… and check out the following related Mad Scientist content on the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the dangers of mirror-imaging, and gaming:

Insights from Ukraine on the Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Warfare

On Surprise Attacks Below the “Bolt from the Blue” Threshold by Lesley Kucharski

Why the Next “Cuban Missile Crisis” Might Not End Well: Cyberwar and Nuclear Crisis Management by Dr. Stephen J. Cimbala

Some Thoughts on Futures Work (Part I) by Dr. Nick Marsella

Gaming the System: How Wargames Shape our Future and associated podcast

Would You Like to Play a Game? Wargaming as a Learning Experience and Key Assumptions Check and “No Option is Excluded” — Using Wargaming to Envision a Chinese Assault on Taiwan, by Ian Sullivan

Using Wargames to Reconceptualize Military Power, by proclaimed Mad Scientist Caroline Duckworth

The Storm After the Flood virtual wargame scenario, video, notes, and Lessons Learned presentation and video, presented by proclaimed Mad Scientists Dr. Gary Ackerman and Doug Clifford, The Center for Advanced Red Teaming, University at Albany, SUNY

Gamers Building the Future Force and associated podcast, with Capt Zach Baumann, Capt Oliver Parsons, and MSgt Michael Sullivan

Fight Club Prepares Lt Col Maddie Novák for Cross-Dimension Manoeuvre, by now COL Arnel David, U.S. Army, and Major Aaron Moore, British Army, along with their interview in The Convergence: UK Fight Club – Gaming the Future Army and associated podcast

About the Author: Nathan Colvin is a Lieutenant Colonel in the TRADOC G-5. He holds a Graduate Certificate in Modeling and Simulations from Old Dominion University, where he is also completing his last semester of coursework toward a Ph.D. in International Studies as an I/ITSEC Leonard P. Gollobin Scholar. He earned master’s degrees in Aeronautics and Space Studies (Embry-Riddle University), Administration (Central Michigan University), and Military Theater Operations (School of Advanced Military Studies). He has deployed to Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Latvia as an aviator, operational planner, and strategist. He is currently participating in the HillVets LEAD program.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).