[Editor’s Note: Army Mad Scientist is pleased to welcome back returning guest blogger and proclaimed Mad Scientist Collin Meisel and newcomer Tim Sweijs with their post addressing the strategic importance small and middle powers play in competition, crisis, and conflict. As General Charles A. Flynn, Commanding General, U.S. Army Pacific (USARPAC), sagely observed in his podcast and blog post last month, “Building strong relationships between individuals, organizations, and countries is vital for deterrence by denial.” From Poland’s pivotal role in the continuing conflict in Ukraine, Messrs. Meisel and Sweijs extrapolate the roles similarly-sized powers could play in the China-US competition in Southeast Asia, both as effective allies and partners, as well as “poison frogs” — whose potential occupation could present our pacing threat with exorbitant and untenable military, diplomatic, and economic costs. In recognizing these small and middle powers’ capacity for regional influence, pursuing opportunities for collaboration, and strengthening bilateral ties, the U.S. can help ensure future global stability — Read on!]

The Russo-Ukraine war of 2022 — a bloody conflict broadcast live from thousands of cellphones from thousands more angles in near-real-time — is one of countless stories that often do not fit neatly into a single narrative. Among many narratives that have surfaced amid Russia’s further invasion of Ukraine are those of a return of great power politics, declining US hegemony, and a crossroads for China’s position in the world — and indeed, each of these stories is important. At the same time, they have, until recently, often overshadowed another important story: that of Poland’s influence and pivotal role in Ukraine.

It is a role that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy movingly acknowledged in a recent virtual appearance in front of Poland’s legislature: “I feel that we have already formed an extremely strong alliance with Poland. Let it be informal. But a union that grew out of reality, not words on paper. If God wills and we win this war, we will share the victory with our brothers and sisters. ”

To date, Poland has accepted the plurality of Ukrainians fleeing the conflict in their homeland. As of 31 March 2022, more than 2.3 million out of 4 million Ukrainian refugees had fled to Poland. These numbers have exceeded even United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees analysts’ worst-case-scenario estimates. Of the millions who have fled (even including those who have not settled in Poland), the majority have passed through Polish territory before continuing onward.

Meanwhile, the lion’s share of NATO-provided military equipment flowing in the opposite direction has passed through or been provided by Poland prior to its final destination in Ukraine. Poland even expressed willingness to donate its 28 MiG-29 fighters to Ukraine’s cause.

While remarkable, Poland’s outsized role is in some sense a natural consequence of its structural connections to Ukraine. The Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures’ Formal Bilateral Influence Capacity Index shows Poland’s importance in Ukraine’s network of diplomatic, economic, and security relationships. According to our most recent data prior to the further Russian invasion, Poland had the single most influence capacity in Ukraine, outpacing even Russia, China, and the United States.

Importantly, a country’s relational power is its capacity to influence another state through economic, political, and/or security measures -- whether a country chooses to leverage that capacity is often a case-dependent political choice. Today, we are seeing Poland leverage this capacity toward positive ends rather than via “weaponized interdependence” often associated with great powers, where countries exploit asymmetric trade, aid, and arms relationships, among others.

Poland’s rise to become the top influencer in Ukraine has resulted from the vacuum left by Russia since the start of its war with Ukraine in 2014. As Russo-Ukrainian bilateral goods trade in particular plummeted, Poland has stepped in to partially fill the gap. This helped boost Poland’s influence capacity in Ukraine, leapfrogging traditional regional and global power players, including the United States, China, and Germany.

Poland’s role in the current crisis has extended beyond government, becoming a society-wide effort, including citizen initiatives for refugee transportation inward, and body armor and food rations, amongst others, outward. Even the Polish diaspora appears to be taking the lead in communities abroad, sparking a grassroots aid effort to assist fleeing Ukrainians. These person-to-person connections -- including personal connections among government leaders -- highlight Poland’s deep ties to Ukraine despite scars of decades past.

Adding in this last layer -- connections at the leader level -- to the logic of structural connections between societies, we again see Poland’s important role in Ukrainian international relations, alongside more traditional power players in Europe.

With these connections and Poles’ strong support for Ukraine in recent days, Poland is illustrating the crucial role that small and middle powers continue to play, even in this new era of great power politics. This advances our conversations regarding such powers beyond the logic of “pivot states," or countries within which great powers vie for influence, or geostrategic footholds, where commercial, political, and military ties provide a means for great powers to extend or maintain what to some amount to modern day empires. Rather, small and middle powers play strategically important roles in their own right, with the ability to make important international contributions both in times of peace and in times of crisis and conflict.

In the midst of important conversations about great powers’ spheres of influence and what they can tell us about the war in Ukraine -- the outcomes of which are crucial, to be sure -- spare a thought for the Poles and the Polands of the world. They will continue to be important in influencing the trajectory of the current crisis, and will likely play an important role in the next one as well. Great powers ignore or dismiss the role of small and middle powers at their own peril.

China-US competition in Southeast Asia comes to mind. Both China and the US have the opportunity to further ratchet up bilateral tensions, or eschew conflict for managed competition that accommodates rather than coerces the aims and interests of smaller regional powers.

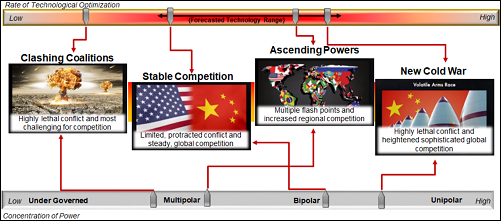

In the event of heightened competition and even the lead-up to conflict in East and Southeast Asia, a plausible outcome of both the “New Cold War” and “Ascending Powers” scenarios posited by the U.S. Army Futures Command’s Future Operational Environment 2035-2050 pamphlet, small and middle powers will likely have the ability to play both the role of effective contributor and enabler but also of spoiler.

In the lead-up to conflict, small and middle powers will have the ability to implement potent deterrence by denial strategies. In Poland, for example, this would be expected to manifest in the form of increased investments in anti-ship missiles and submarines, long-range precision fires and theater ballistic missile defense, and improved intelligence surveillance and reconnaissance capabilities, such as those provided by the PIAST (Polish ImAging SaTellites) nanosatellites project. In East and Southeast Asia, small and middle powers such as Taiwan are investing in similar capabilities. Additionally, they can transform  difficult-to-defend, island territories into “poison frogs,” where the military, diplomatic, and economic cost of taking and holding such territory is high. Collectively, such strategies will greatly strengthen the position of any great power with which countries may choose to align themselves and reduce the defense burden for the great power.

difficult-to-defend, island territories into “poison frogs,” where the military, diplomatic, and economic cost of taking and holding such territory is high. Collectively, such strategies will greatly strengthen the position of any great power with which countries may choose to align themselves and reduce the defense burden for the great power.

Alternatively, small and middle powers possess the ability to destabilize the international system and increase the likelihood of great power conflict. In an unstable international hierarchy with tight alliance systems -- think a “New Cold War” with a rising China and affiliated illiberal actors contesting the US’s position as the world’s leading power -- small powers can also be spoilers for international stability for a variety of reasons. Their geographic position and inability to fend for themselves can make them a stepping stone in expansionist strategies of great powers. Their role can be considered indispensable by great powers for fear that their loss will lead to domino-effects. And reckless behavior on the part of the small and middle power themselves can make them a moral hazard that can drag great power partners and allies into a wider conflict, and even lead to the outbreak of great power war. Here the “poison frog” transforms into the poisonous friend.

Although US influence in Southeast Asia -- and the attendant likelihood of gaining additional small and middle power regional partners -- has been on the decline, the future outcome of competition in the region is still very much an open question. Meanwhile, the U.S. Army will need to “get comfortable with contestation and get comfortable with collaboration.”

To the extent that great powers can recognize the important role that small and middle powers play in the international system, and are able to leverage their influence capacity, the world may become a more stable place.

Fortunately, Poland’s support for Ukraine thus far is substantially advancing its partners and allies interests in Ukraine’s conflict with Russia, facilitated by the US, which is keeping a close watch on escalatory actions that could drag NATO into the war. Whether other small and middle powers will act similarly in potential future conflicts will depend in part on how they are engaged by great powers today.

If you liked this post, check out Collin Meisel's previous post, co-authored with fellow proclaimed Mad Scientist Dr. Jonathan D. Moyer -- On Hype and Hyperwar

.. and review the following related content:

Russia-Ukraine Conflict: Sign Post to the Future (Part 1), by Kate Kilgore

The Most Consequential Adversaries, and associated podcast, with General Charles A. Flynn

The Operational Environment (2021-2030): Great Power Competition, Crisis, and Conflict, its source document, and Threats to 2030 video

The Future Operational Environment: The Four Worlds of 2035-2050, the complete AFC Pamphlet 525-2, Future Operational Environment: Forging the Future in an Uncertain World 2035-2050, and associated video

Competition and Conflict in the Next Decade

Disrupting the “Chinese Dream” – Eight Insights on how to win the Competition with China

About the Authors:

Collin Meisel is a Senior Research Associate and Diplometrics Program lead with the University of Denver’s Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures and a subject matter expert with The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies.

Tim Sweijs is the Director of Research at The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies and a senior research fellow at the War Studies Research Centre at the Netherlands Defence Academy.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).