[Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist welcomes back returning guest blogger Ian Sullivan, Assistant G-2, ISR and Futures, TRADOC, with today’s insightful post addressing how China and Russia seek to achieve Decision Dominance and Information Advantage. Excerpted from a larger information paper (find the link at the bottom of this post), Mr. Sullivan explores our adversaries’ distinctive whole of nation approaches to a common objective — winning without fighting and employing standoff capabilities to divide the United States internally, drive a wedge between us and our allies and partners, and in an operational/tactical sense, split the constituent elements of the Joint Force asunder — Read on!]

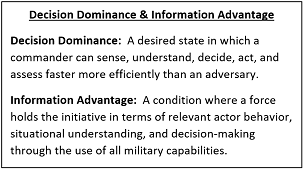

Information is fast becoming the dominant factor in all levels of Great Power competition, crisis, and conflict. Maintaining an information advantage over our potential adversaries — across the Diplomatic, Information, Military, and Economic (DIME) spheres, and then, in terms of military operations, at all echelons in a Joint and Combined way — will be the most critical factor in  determining success in all operations, now and in the future. As the Army contemplates its role in this process, it is coalescing its thoughts around the idea of seeking Decision Dominance by maintaining an Information Advantage over our adversaries (see figure). However, our pacing threat (China) and our near-peer threat (Russia) also have sophisticated approaches to the use of information, and in some ways maintain unique advantages in this realm.

determining success in all operations, now and in the future. As the Army contemplates its role in this process, it is coalescing its thoughts around the idea of seeking Decision Dominance by maintaining an Information Advantage over our adversaries (see figure). However, our pacing threat (China) and our near-peer threat (Russia) also have sophisticated approaches to the use of information, and in some ways maintain unique advantages in this realm.

China: Political Warfare for an Intelligentized Age

China has developed a unique approach to operations in the Information Domain (ID), converging traditional Marxist-Leninist notions surrounding political warfare,1 and advancing them to take advantage of the opportunities that Beijing’s whole-of-nation power brings to the high-tech, intelligentized  age. Chinese information operations generally operate around a unified theme pushing well developed narratives designed to gain influence across the globe where it can, and to effectively deter and undermine the efforts of nations it views as hostile to its inevitable (through the eyes of Beijing) rise. The narratives generally center on the idea that China is rapidly becoming a global power and that their approach to international relations/discourse is superior to that of the West.

age. Chinese information operations generally operate around a unified theme pushing well developed narratives designed to gain influence across the globe where it can, and to effectively deter and undermine the efforts of nations it views as hostile to its inevitable (through the eyes of Beijing) rise. The narratives generally center on the idea that China is rapidly becoming a global power and that their approach to international relations/discourse is superior to that of the West.

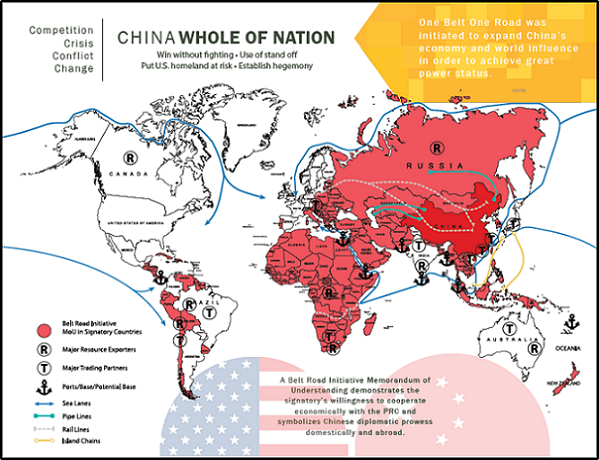

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been building what it calls “discourse power” by shaping a narrative that its model of government is superior to democratic government structures.2 They argue that China, who suffered generations of humiliation in a global system dominated by others (especially Westerners), is the future. And unlike US/Western efforts in the information arena, Beijing works to match words and actions in an integrated fashion. The Belt and Road Initiative is such an integrated effort designed to boldly demonstrate across the DIME that China is the up and coming power with global reach and impact.

It is increasingly clear that China’s information efforts are aimed squarely at the United States and its Allies and Partners as its arch rival/foil. A telling example was the “Wolf Warrior” campaign, undertaken by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This effort drew upon the very popular series of Wolf Warrior movies in China that push a pro-China message of toughness in the face of their adversaries.3 The Wolf Warrior diplomats represented a fundamental change for Chinese diplomacy — instructed to be fiery, bold, and to push back repeatedly at perceived insults of China wherever they were in the world. This effort was integrated with social media platforms both internal to China and on Western platforms like Twitter and Facebook.  It came to the forefront with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and China’s “mask diplomacy,” where they gave out PPE, masks, and eventually vaccines around the globe and used both white (i.e., overt) and black (i.e., covert) propaganda to show the impact of their efforts.

It came to the forefront with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and China’s “mask diplomacy,” where they gave out PPE, masks, and eventually vaccines around the globe and used both white (i.e., overt) and black (i.e., covert) propaganda to show the impact of their efforts.

The Wolf Warrior narrative targeted China’s internal and external audiences simultaneously. Internally, it showed that China was being aggressive on the world stage, and was pushing against the West. This narrative played on the views of a significant portion of China’s youth who are highly supportive of an aggressive, world-leading power known as the “Young Pinks.” At the same time, it demonstrates to the international community that China is a leader and that its activities and system are superior to the West.

The PLA is an active component of China’s broader Political Warfare efforts, and it works to help achieve China’s national-level information goals, as well as to establish its own form of Decision Dominance and Information Advantage for its own military operations. Indeed, the PLA’s active participation in these efforts, along with the key role it plays within the civil-military fusion construct transforms the original Political Warfare definition into something akin to confrontational competition, which provides a more operationalized form of Political Warfare, broadens it, and gives it other avenues of advance against an adversary.

The key element of this approach is the “Three Warfares Doctrine” — the PLA’s effort to frame its operations within the information environment. The Three Warfares operates along three interrelated lines of effort: Media Warfare; Psychological Warfare; and Legal Warfare (sometimes called “lawfare”). Taken together, these provide the PLA with a capability to control perceptions and shape the narrative, while undermining those of an opponent. This likely is designed for use in competition, but becomes essential in crisis as they work to set conditions for a transition to conflict in their favor. It also may provide them with a way to maintain a narrative edge in conflict and perhaps even allow for off-ramps in China’s favor.4

While the PLA plays a critical role in China’s whole of nation confrontational competition effort, it also recognizes the centrality of information in terms of military operations. More accurately, it understands the imperative for transitioning from informationized warfare to intelligentized warfare, where the PLA can augment its already formidable understanding of how to use information and merge it with new technologies, such as artificial intelligence,  quantum computing, big-date analytics, cloud computing, and unmanned systems.5 Where “informationized” warfare focused on ways to weaken an adversary’s ability to acquire, transmit, process, and use information during warfare, and seek their capitulation prior to the start of conflict; its “intelligentized” warfare concept will target the enemy’s information itself — targeting its AI, its big data — all in an effort to shape the cognitive realm, which becomes a separate warfighting domain. A strand of thinking within the PLA calls for it being able to seize “war control,” or the ability to precisely control and adjust warfighting intensity and scope to achieve the objectives for which the war is fought.6 When taken together, the idea of intelligentized warfare is all about war control, and information is at its heart.

quantum computing, big-date analytics, cloud computing, and unmanned systems.5 Where “informationized” warfare focused on ways to weaken an adversary’s ability to acquire, transmit, process, and use information during warfare, and seek their capitulation prior to the start of conflict; its “intelligentized” warfare concept will target the enemy’s information itself — targeting its AI, its big data — all in an effort to shape the cognitive realm, which becomes a separate warfighting domain. A strand of thinking within the PLA calls for it being able to seize “war control,” or the ability to precisely control and adjust warfighting intensity and scope to achieve the objectives for which the war is fought.6 When taken together, the idea of intelligentized warfare is all about war control, and information is at its heart.

The PLA is doing more, however, than simply talking about how to carry out information-related operations. In 2015, they created the Strategic Support Force (PLASSF) as a separate branch of its Armed Forces. The creation of this entity signaled the importance of informationized operations, and its continued development and successes place it at the very forefront of the shift to intelligentized warfare and as the PLA’s operational arm of its information-related activities. It brings together under one command space, cyber, electronic warfare, and information operations capabilities. It is considered a “new-type combat force,” and its creation demonstrates the importance of information dominance to China’s way of war. The PLASSF inherits both offensive and defensive information operations, and it will play a central role in carrying out the PLA’s efforts to secure information dominance and target its enemy’s decision-making cycle.

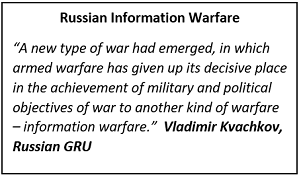

Russia: Information Confrontation [Informatsionnoe provivoborstvo, or IPb] Turns Weakness into Strength

Russia is the most capable actor in the information dimension – its ability to synchronize information effects across all mediums is unmatched. Russia, and its Soviet predecessors, have a long history of using information to advance its national interests and objectives. Russia’s current approach to information operations — Information Confrontation — takes advantage of three contemporary Operational Environment characteristics: 1) the character of modern warfare; 2) the global interconnectedness of the information domain; and 3) the prominence of non-governmental organizations in the international order who can serve as witting partners or unwitting pawns for Moscow’s information activities.7

Russia is the most capable actor in the information dimension – its ability to synchronize information effects across all mediums is unmatched. Russia, and its Soviet predecessors, have a long history of using information to advance its national interests and objectives. Russia’s current approach to information operations — Information Confrontation — takes advantage of three contemporary Operational Environment characteristics: 1) the character of modern warfare; 2) the global interconnectedness of the information domain; and 3) the prominence of non-governmental organizations in the international order who can serve as witting partners or unwitting pawns for Moscow’s information activities.7  Russia’s Information Confrontation is aimed directly at the United States and its NATO Allies and European partners, and it targets the key vulnerabilities Moscow perceives in their open, democratic societies. At its core, Information Confrontation is designed to create confusion and sow doubt in the existence of truth, complicating an adversary’s decision-making and undermining their will to fight. If done correctly, Information Confrontation keeps the Kremlin at a threshold below armed conflict, allowing it to “win without fighting.”

Russia’s Information Confrontation is aimed directly at the United States and its NATO Allies and European partners, and it targets the key vulnerabilities Moscow perceives in their open, democratic societies. At its core, Information Confrontation is designed to create confusion and sow doubt in the existence of truth, complicating an adversary’s decision-making and undermining their will to fight. If done correctly, Information Confrontation keeps the Kremlin at a threshold below armed conflict, allowing it to “win without fighting.”

Information Confrontation offers a two-pronged pathway to secure a form of Decision Dominance over its adversaries. The first is information technical operations, designed to target, disrupt, exploit, manipulate, or destroy an adversary’s C4ISR and other systems a society needs to function. This involves a combination of cyber operations, space and counter-space efforts, and electronic warfare at all echelons. The second is information psychological operations, designed to exploit and exacerbate pre-existing societal divisions, and affect the cognitive realm and emotions of targeted audiences and individuals.8 In the Russian concept of information confrontation, there is no distinction between where information resides, be it on a system or in the human mind, just like there is no distinction between how information is transferred between those two repositories.9

It must be noted that Russia’s use of information is, for them, a defensive response to an overly aggressive United States (and NATO), but also a response to its own perceived military weakness when compared to its main adversaries.10 Nevertheless, while Russia may consider information operations a defensive response, their approach and doctrine to these operations states that they are “always at war” in the information space.11 Information confrontation activities allow Moscow to control escalation and stay under the threshold of war, while still directly competing with its main adversary on a global level. It also considers information confrontation to be a form of deterrence it can employ against an adversary in a place where Moscow may believe it has a form of dominance.

It must be noted that Russia’s use of information is, for them, a defensive response to an overly aggressive United States (and NATO), but also a response to its own perceived military weakness when compared to its main adversaries.10 Nevertheless, while Russia may consider information operations a defensive response, their approach and doctrine to these operations states that they are “always at war” in the information space.11 Information confrontation activities allow Moscow to control escalation and stay under the threshold of war, while still directly competing with its main adversary on a global level. It also considers information confrontation to be a form of deterrence it can employ against an adversary in a place where Moscow may believe it has a form of dominance.

Like China, Russia’s information activities reflect a whole of nation approach, involving all elements of Russian national power. Russian strategic documents describe the importance of information as a means to influence international opinion and secure its position as one of the world’s leading nations. Moscow’s international efforts focus on developing effective ways to influence foreign audiences and deliver what it terms “unbiased” views of Russia and its actions. They seek to use social media and also engage with thought leaders in the academic world and with NGOs to help set the international security dialogue. In short, Russia’s information confrontation approach is all about setting the narratives it wishes to convey and countering those it wishes to suppress.12

Like China, Russia’s information activities reflect a whole of nation approach, involving all elements of Russian national power. Russian strategic documents describe the importance of information as a means to influence international opinion and secure its position as one of the world’s leading nations. Moscow’s international efforts focus on developing effective ways to influence foreign audiences and deliver what it terms “unbiased” views of Russia and its actions. They seek to use social media and also engage with thought leaders in the academic world and with NGOs to help set the international security dialogue. In short, Russia’s information confrontation approach is all about setting the narratives it wishes to convey and countering those it wishes to suppress.12

The Defense Intelligence Agency defines information confrontation as Russia’s term for conflict in the information sphere. They assess it includes diplomatic, economic, military, political, cultural, social, and religious arenas across both the information technical and information psychological lines of effort.13 Russia’s information confrontation allows Moscow to wage a more focused effort against a broader series of targets, and often with a degree of plausible deniability that makes it very difficult to determine Moscow’s role in the effort. Moscow’s ability to effectively use social media content (white, gray, and black) to shape opinions means that they can — with very little effort, and often using private entities and cut-outs — impact whole populations vice a handful of targets.14 This has been on display across the United States and Europe as Moscow conducted operations aimed at influence a variety of political elections and to sow broader societal dissent on hot-button issues.

Russian Information operators are experts in understanding and leveraging key fault lines in the U.S. domestic base. They excel at sowing political discord in domestic audiences and target audiences. They are on a continuous campaign to spread misinformation and disinformation to create internal strife, change attitudes and behaviors, and cause polarization in domestic U.S. audiences. Their operators are given free rein to post on social media, hack and post stolen information, and build online support against political enemies. For example, during the 2016 U.S. Elections, Russia’s Internet Research Agency (IRA) used gray and black information operations on social media to organize rallies, promote their preferred candidate with gray and black tropes, and discredit the candidate they did not prefer.

Russian Information operators are experts in understanding and leveraging key fault lines in the U.S. domestic base. They excel at sowing political discord in domestic audiences and target audiences. They are on a continuous campaign to spread misinformation and disinformation to create internal strife, change attitudes and behaviors, and cause polarization in domestic U.S. audiences. Their operators are given free rein to post on social media, hack and post stolen information, and build online support against political enemies. For example, during the 2016 U.S. Elections, Russia’s Internet Research Agency (IRA) used gray and black information operations on social media to organize rallies, promote their preferred candidate with gray and black tropes, and discredit the candidate they did not prefer.

Like China, there is a military component to Russia’s information confrontation efforts. It may not be the main effort, as the intent of Moscow’s approach to information is stay below the conflict threshold, but these operations clearly are linked to military operations. Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, GEN Valery Gerasimov famously wrote that the ratio of non-military means to military means in contemporary Great Power military conflict is 4:1. Furthermore, while the military has significant capabilities that can come to bear in the ID – including some cyber capabilities, intelligence capabilities, space and counter-space capabilities, and a great deal of EW capabilities – the vast majority of Moscow’s ability to influence opinion resides outside of the military, and sometimes outside of the government.15

The military can, however, benefit from the broader elements of Russia’s whole-of-nation information operations. Significant information confrontation activities surrounded Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008 and Russia’s annexation of the Crimea from Ukraine in 2014. These activities caused confusion, particularly the infamous “little green men” who spearheaded the military move into Crimea who could not directly be attributed to Russia. Even military exercises, like the recently-concluded ZAPAD 21 in the Western Military District had a significant information theme, as do ongoing Russian operations in Ukraine, while Russia’s recent large-scale deployments to the Ukrainian border clearly was intended as an information confrontation activity designed to undermine Ukrainian resolve, NATO willpower, and to set the agenda of Russia as a world leader.

Both China and Russia have well-developed approaches to information operations, and in their own ways, seek to achieve Decision Dominance and Information Advantage. Their approaches seek to achieve some of the same advantages the U.S. Army considers when discussing these terms. When we talk about China and Russia in terms of competition, crisis, and conflict, we often note that they both attempt to: 1) win without fighting; and 2) use standoff capabilities to separate the United States internally, from our allies and partners, and in an operational/tactical sense, separate the constituent elements of the Joint Force. These objectives make information a central element of their Great Power competition, which they use to help dominate in crisis and conflict, while at the same time attempting to control escalation and quickly achieve their objectives. Their respective weaponized approach to information may be the most effective “standoff” weapon that our adversaries wield.

If you enjoyed this post, read Ian Sullivan‘s comprehensive information paper from which it was excerpted here.

… download and check out The Operational Environment (2021-2030): Great Power Competition, Crisis, and Conflict.

… browse the TRADOC G-2’s China and Russia Product pages.

… and explore the following related MadSci content:

Young Minds on Competition and Conflict

Competition and Conflict in the Next Decade

The Future of War is Cyber! by CPT Casey Igo and CPT Christian Turley

A House Divided: Microtargeting and the next Great American Threat, by 1LT Carlin Keally

Sub-threshold Maneuver and the Flanking of U.S. National Security, by Dr. Russell Glenn

Global Entanglement and Multi-Reality Warfare and associated podcast, with COL Stefan Banach (USA-Ret.)

Hybrid Threats and Liminal Warfare and associated podcast, with Dr. David Kilcullen

The Erosion of National Will – Implications for the Future Strategist, by Dr. Nick Marsella

Weaponized Information: What We’ve Learned So Far…, Insights from the Mad Scientist Weaponized Information Series of Virtual Events, and all of this series’ associated content and videos [access via a non-DoD network]

Weaponized Information: One Possible Vignette and Three Best Information Warfare Vignettes

>>>> REMINDER: Army Mad Scientist Fall / Winter Writing Contest:  Crowdsourcing is an effective tool for harvesting ideas, thoughts, and concepts from a wide variety of interested individuals, helping to diversify thought and challenge conventional assumptions. Army Mad Scientist seeks to crowdsource the intellect of the Nation (You!) with our Fall / Winter Writing Contest’s two themes — Back to the Future and Divergence – check out the associated writing prompts in the contest flyer and announcement, then get busy crafting your submissions — entries will be accepted in two formats:

Crowdsourcing is an effective tool for harvesting ideas, thoughts, and concepts from a wide variety of interested individuals, helping to diversify thought and challenge conventional assumptions. Army Mad Scientist seeks to crowdsource the intellect of the Nation (You!) with our Fall / Winter Writing Contest’s two themes — Back to the Future and Divergence – check out the associated writing prompts in the contest flyer and announcement, then get busy crafting your submissions — entries will be accepted in two formats:

Written essay (no more than 1500 words, please!)

Tweet @ArmyMadSci, using either #MadSciBacktotheFuture or #MadSciDivergence

We will pick a winner from each of these two formats!

Contest Winners will be proclaimed official Mad Scientists and be featured in the Mad Scientist Laboratory. Semi-finalists of merit will also be published!

Contest Winners will be proclaimed official Mad Scientists and be featured in the Mad Scientist Laboratory. Semi-finalists of merit will also be published!

DEADLINE: All entries are due NLT 11:59 pm Eastern on January 10, 2022!

Any questions? Don’t hesitate to reach out to us — send us an eMail at: madscitradoc@gmail.com

Sincere thanks go to Mr. David May (DISL), the Senior Cyber Intelligence Advisor at the Cyber Center of Excellence and to COL Justine Krumm, the G-2 of Army Cyber Command for their thoughtful insights, additions, and commentary on this paper.

Ian Sullivan is the Assistant G-2, ISR and Futures, at Headquarters, TRADOC.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

1 Peter Mattis, “China’s ‘Three Warfares’ In Perspective,” War on the Rocks, 30 January 2018.

2 Edwin S. Cochran, “China’s ‘Three Warfares’: People’s Liberation Army Influence Operations,” International Bulletin of Political Psychology, Volume 20, Issue 3, 7 September 2020, 3-4.

3 Jessica Brandt and Bret Schafer, “How China’s ‘Wolf Warrior’ Diplomats Use and Abuse Twitter,” Brookings Tech Stream, 28 October 2020; and Yaoyo Dai and Luwei Rose Luquiu, “China’s ‘Wolf Warrior’ Diplomats Like to Talk Tough,” The Washington Post, 12 May 2021.

4 Cochran, 2-9.

5 Mark Pomerleau, “China Moves Toward New ‘Intelligentized’ Approach to Warfare, Says Pentagon,” C4ISRNet, 1 September 2020.

6 John Dotson and Howard Wang, “The “Algrorithm Game’ and Its Implications for Chinese War Control,” The Jamestown Foundation, China Brief Volume 19, Issue 7, 9 April 2019.

7 Lesley Kucharski, “Russian Multi-Domain Strategy Against NATO: Information Confrontation and US Forward-Deployed Nuclear Weapons in Europe,” Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, 2018, 3.

8 Defense Intelligence Agency, “Russia Military Power: Building a Military to Support Great Power Aspiration,” 2017, 38.

9 Kucharski, 4; and Keir Giles, Handbook of Russian Information Warfare, NATO Defense College Fellowship Monograph, November 2016, 6-7.

10 Kucharski, 4-5; and Michel Duclos, “Russia’s National Security Strategy 2021: The Era of ‘Information Confrontation’”, Institute Montaigne, 2 August 2021.

11 US Department of State Global Engagement Center, “GEC Special Report: Pillars of Russia’s Disinformation and Propaganda Ecosystem,” August 2020, 6.

12 Ibid., 5.

13 DIA, 37-39.

14 Kucharski, 3-6.

15 Blagovest Tashev, Michael Purcell, and Brian McLaughlin, “Russia’s Information Warfare: Exploring the Cognitive Dimension,” Marine Corps University Journal, Volume 10, No. 2, Fall 2019, 129-131.