(Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist Laboratory is pleased to present a new post by returning guest blogger Dr. Richard Nabors addressing the four key practices of innovation. Dr. Nabors’ previous guest posts discussed how integrated sensor systems will provide Future Soldiers with the requisite situational awareness to fight and win in increasingly complex and advanced battlespaces, and how Augmented and Mixed Reality are the critical elements required for these integrated sensor systems to become truly operational and support Soldiers’ needs in complex environments.)

For the U.S. military to maintain its overmatch capabilities, innovation is an absolute necessity. As noted in The Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Future Warfare, our adversaries will continue to aggressively pursue rapid innovation in key technologies in order to challenge U.S. forces across multiple domains. Because of its vital necessity, U.S. innovation cannot be left solely to the development of serendipitous discoveries.

For the U.S. military to maintain its overmatch capabilities, innovation is an absolute necessity. As noted in The Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Future Warfare, our adversaries will continue to aggressively pursue rapid innovation in key technologies in order to challenge U.S. forces across multiple domains. Because of its vital necessity, U.S. innovation cannot be left solely to the development of serendipitous discoveries.

The Army has successfully generated innovative programs and transitioned them from the research community into military use. In the process, it has identified four key practices that can be used in the future development of innovative programs. These practices – identifying the need, the vision, the expertise, and the resources – are essential in preparing for warfare in the Future Operational Environment. The recently completed Third Generation Forward Looking Infrared (3rd Gen FLIR) program provides us with a contemporary use case regarding how each of these practices are key to the success of future innovations.

1. Identifying the NEED:

1. Identifying the NEED:

To increase speed, precision, and accuracy of a platform lethality, while at the same time increasing mission effectiveness and warfighter safety and survivability.

As the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) noted in its Advanced Engagement Battlespace assessment, future Advanced Engagements will be…

… compressed in time, as the speed of weapon delivery and their associated effects accelerate enormously;

… extended in space, in many cases to a global extent, via precision long-range strike and interconnectedness, particularly in the information environment;

… far more lethal, by virtue of ubiquitous sensors, proliferated precision, high kinetic energy weapons and advanced area munitions;

… routinely interconnected – and contested — across the multiple domains of air, land, sea, space and cyber; and

… interactive across the multiple dimensions of conflict, not only across every domain in the physical dimension, but also the cognitive dimension of information operations, and even the moral dimension of belief and values.

Identifying the NEED within the context of these future Advanced Engagement characteristics is critical to the success of future innovations.

The first-generation FLIR systems gave a limited ability to detect objects on the battlefield at night. They were large, slow, and provided low-resolution, short-range images. The need was for greater speed, precision, and range in the targeting process to unlock the full potential of infrared imaging. Third generation FLIR uses multiband infrared imaging sensors combined with multiple fields of view which are integrated with computer software to automatically enhance images in real-time. Sensors can be used across multiple platforms and missions, allowing optimization of equipment for battlefield conditions, greatly enhancing mission effectiveness and survivability, and providing significant cost savings.

To look beyond the need and what is possible to what could be possible.

As we look forward into the Future Operational Environment, we must address those revolutionary technologies that, when developed and fielded, will provide a decisive edge over adversaries not similarly equipped. These potential Game Changers include:

• Laser and Radio Frequency Weapons – Scalable lethal and non-Lethal directed energy weapons can counter Aircraft, UAS, Missiles, Projectiles, Sensors, and Swarms.

• Swarms – Leverage autonomy, robotics, and artificial intelligence to generate “global behavior with local rules” for multiple entities – either homogeneous or heterogeneous teams.

• Rail Guns and Enhanced Directed Kinetic Energy Weapons (EDKEW) – Non explosive electromagnetic projectile launchers provide high velocity/high energy weapons.

• Energetics – Provides increased accuracy and muzzle energy.

• Synthetic Biology – Engineering and modification of biological entities has potential weaponization.

• Internet of Things – Linked internet “things” create opportunity and vulnerability. Great potential benefits already found in developing U.S. systems also create a vulnerability.

• Power – Future effectiveness depends on renewable sources and reduced consumption. Small nuclear reactors are potentially a cost-effective source of stable power.

Understanding these Future Operational Environment Game Changers is central to identifying the VISION and looking beyond the need to what could be possible.

The 3rd Gen FLIR program struggled early in its development to identify requirements necessary to sustain a successful program. Without the user community’s understanding of a vision of what could be possible, requirements were based around the perceived limitations of what technology could provide. To overcome this, the research community developed a comprehensive strategy for educational outreach to the Army’s requirement developers, military officers, and industry on the full potential of what 3rd Gen FLIR could achieve. This campaign highlighted not only the recognized need, but also a vision for what was possible, and served as the catalyst to bring the entire community together.

3. Identifying the EXPERTISE:

3. Identifying the EXPERTISE:

To gather expertise from all possible sources into a comprehensive solution.

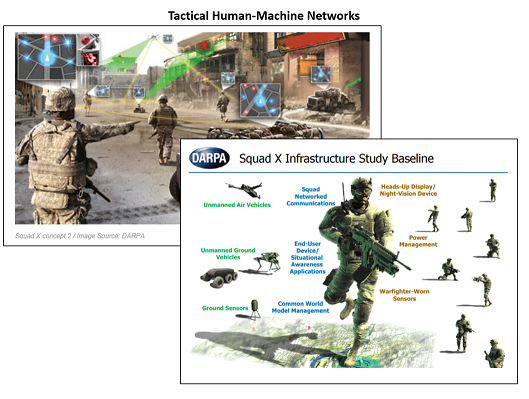

Human creativity is the most transformative force in the world; people compound the rate of innovation and technology development. This expertise is fueling the convergence of technologies that is already leading to revolutionary achievements with respect to sensing, data acquisition and retrieval, and computer processing hardware.

Identifying the EXPERTISE leads to the exponential convergence and innovation that will afford strategic advantage to those who recognize and leverage them.

The expertise required to achieve 3rd Gen FLIR success was from the integration of more than 16 significant research and development projects from multiple organizations: Small Business Innovation Research programs; applied research funding, partnering in-house expertise with external communities; Manufacturing Technology (ManTech) initiatives, working with manufacturers to develop the technology and long-term manufacturing capabilities; and advanced technology development funding with traditional large defense contractors. The talented workforce of the Army research community strategically aligned these individual activities and worked with them to provide a comprehensive, interconnected final solution.

4. Identifying the RESOURCES:

4. Identifying the RESOURCES:

To consistently invest in innovative technology by partnering with others to create multiple funding sources.

The 2017 National Security Strategy introduced the National Security Innovation Base as a critical component of its vision of American security. In order to meet the challenges of the Future Operational Environment, the Department of Defense and other agencies must establish strategic partnerships with U.S. companies to help align private sector Research and Development (R&D) resources to priority national security applications in order to nurture innovation.

The development of 3rd Gen FLIR took many years of appropriate, consistent investments into innovations and technology breakthroughs. Obtaining the support of industry and leveraging their internal R&D investments required the Army to build trust in the overall program. By creating partnerships with others, such as the U.S. Army Communications-Electronics Research, Development and Engineering Center (CERDEC) and ManTech, 3rd Gen FLIR was able to integrate multiple funding sources to ensure a secure resource foundation.

CONCLUSION

The successful 3rd Gen FLIR program is a prototype of the implementation of an innovative program, which transitions good ideas into actual capabilities. It exemplifies how identifying the need, the vision, the expertise and the resources can create an environment where innovation thrives, equipping warriors with the best technology in the world. As the Army looks to increase its exploration of innovative technology development for the future, these examples of past successes can serve as models to build on moving forward.

See our Prototype Warfare post to learn more about other contemporary innovation successes that are helping the U.S. maintain its competitive advantage and win in an increasingly contested Operational Environment.

Dr. Richard Nabors is Associate Director for Strategic Planning and Deputy Director, Operations Division, U.S. Army Research, Development and Engineering Command (RDECOM) Communications-Electronics Research, Development and Engineering Center (CERDEC), Night Vision and Electronic Sensors Directorate.

The character of war, strategy development, and operational level challenges are changing; therefore operational approaches must do the same.

The character of war, strategy development, and operational level challenges are changing; therefore operational approaches must do the same.