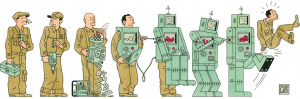

The Mad Scientist team participates in many thought exercises, tabletops, and wargames associated with how we will live, work, and fight in the future. A consistent theme in these events is the idea that a major barrier to the integration of robotic systems into Army formations is a lack of trust between humans and machines. This assumption rings true as we hear the  media and opinion polls describe how society doesn’t trust some disruptive technologies, like driverless cars or the robots coming for our jobs.

media and opinion polls describe how society doesn’t trust some disruptive technologies, like driverless cars or the robots coming for our jobs.

In his recent book, Army of None, Paul Scharre describes an event that nearly led to a nuclear confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States.  On September 26, 1983, LTC Stanislav Petrov, a Soviet Officer serving in a bunker outside Moscow was alerted to a U.S. missile launch by a recently deployed space-based early warning system. The Soviet Officer trusted his “gut” – or experientially informed intuition – that this was a false alarm.

On September 26, 1983, LTC Stanislav Petrov, a Soviet Officer serving in a bunker outside Moscow was alerted to a U.S. missile launch by a recently deployed space-based early warning system. The Soviet Officer trusted his “gut” – or experientially informed intuition – that this was a false alarm.  His gut was right and the world was saved from an inadvertent nuclear exchange because this officer did not over trust the system. But is this the rule or an exception to how humans interact with technology?

His gut was right and the world was saved from an inadvertent nuclear exchange because this officer did not over trust the system. But is this the rule or an exception to how humans interact with technology?

The subject of trust between Soldiers, Soldiers and Leaders, and the Army and society is central to the idea of the Army as a profession. At the most tactical level, trust is seen as essential to combat readiness as Soldiers must trust each other in dangerous situations. Humans naturally learn to trust their peers and subordinates once they have worked with them for a period of time. You learn what someone’s strengths and weaknesses are, what they can handle, and under what conditions they will struggle. This human dynamic does not translate to human-machine interaction and the tendency to anthropomorphize machines could be a huge barrier.

The subject of trust between Soldiers, Soldiers and Leaders, and the Army and society is central to the idea of the Army as a profession. At the most tactical level, trust is seen as essential to combat readiness as Soldiers must trust each other in dangerous situations. Humans naturally learn to trust their peers and subordinates once they have worked with them for a period of time. You learn what someone’s strengths and weaknesses are, what they can handle, and under what conditions they will struggle. This human dynamic does not translate to human-machine interaction and the tendency to anthropomorphize machines could be a huge barrier.

We recommend that the Army explore the possibility that Soldiers and Leaders could over trust AI and robotic systems. Over trust of these systems could blunt human expertise, judgement, and intuition thought to be critical to winning in complex operational environments. Also, over trust might lead to additional adversarial vulnerabilities such as deception and spoofing.

We recommend that the Army explore the possibility that Soldiers and Leaders could over trust AI and robotic systems. Over trust of these systems could blunt human expertise, judgement, and intuition thought to be critical to winning in complex operational environments. Also, over trust might lead to additional adversarial vulnerabilities such as deception and spoofing.

In 2016, a research team at the Georgia Institute of Technology revealed the results of a study entitled “Overtrust of Robots in Emergency Evacuation Scenarios”. The research team put 42 test participants into a fire emergency with a robot responsible for escorting them to an emergency exit. As the robot passed obvious exits and got lost, 37 participants continued to follow the robot and an additional 2 stood with the robot and didn’t move towards either exit. The study’s takeaway was that roboticists must think about programs that will help humans establish an “appropriate level of trust” with robot teammates.

In 2016, a research team at the Georgia Institute of Technology revealed the results of a study entitled “Overtrust of Robots in Emergency Evacuation Scenarios”. The research team put 42 test participants into a fire emergency with a robot responsible for escorting them to an emergency exit. As the robot passed obvious exits and got lost, 37 participants continued to follow the robot and an additional 2 stood with the robot and didn’t move towards either exit. The study’s takeaway was that roboticists must think about programs that will help humans establish an “appropriate level of trust” with robot teammates.

In Future Crimes, Marc Goodman writes of the idea of “In Screen We Trust” and the vulnerabilities this trust builds into our interaction with our automation. His example of the cyber-attack against the Iranian uranium enrichment centrifuges highlights the vulnerability of experts believing or trusting their screens against mounting evidence that something else might be contributing to the failure of centrifuges.  These experts over trusted their technology or just did not have an “appropriate level of trust”. What does this have to do with Soldiers on the future battlefield? Well, increasingly we depend on our screens and, in the future, our heads-up displays to translate the world around us. This translation will only become more demanding on the future battlefield with war at machine speed.

These experts over trusted their technology or just did not have an “appropriate level of trust”. What does this have to do with Soldiers on the future battlefield? Well, increasingly we depend on our screens and, in the future, our heads-up displays to translate the world around us. This translation will only become more demanding on the future battlefield with war at machine speed.

So what should our assumptions be about trust and our robotic teammates on the future battlefield?

1) Soldiers and Leaders will react differently to technology integration.

2) Capability developers must account for trust building factors in physical design, natural language processing, and voice communication.

3) Intuition and judgement remain a critical component of human-machine teaming and operating on the future battlefield. Speed becomes a major challenge as humans become the weak link.

4) Building an “appropriate level of trust” will need to be part of Leader Development and training. Mere expertise in a field does not prevent over trust when interacting with our robotic teammates.

5) Lastly, lack of trust is not a barrier to AI and robotic integration on the future battlefield. These capabilities will exist in our formations as well as those of our adversaries. The formation that develops the best concepts for effective human-machine teaming, with trust being a major component, will have the advantage.

Interested in learning more on this topic? Watch Dr. Kimberly Jackson Ryan (Draper Labs).

[Editor’s Note: A special word of thanks goes out to fellow Mad Scientist Mr. Paul Scharre for sharing his ideas with the Mad Scientist team regarding this topic.]