[Editor’s Note: Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD, including chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear munitions), remain potent adversarial capabilities — as much for their potential psychological effects as their kinetic or physiological effects. Their use or threatened use, having long been proscribed by treaties, international norms, and policies of deterrence, is making a resurgence in the contemporary Operational Environment.

Nuclear saber-rattling has reached new levels of bellicosity, with former Russian president Dmitry Medvedev repeatedly threatening the West with nuclear war if Russia is pushed back to its internationally recognized 1991 borders in its on-going war in Ukraine. Russia’s President Vladimir Putin recently climbed into the cockpit of a modernized Tu-160 Blackjack strategic bomber for a 30 minute demonstration flight, telegraphing Moscow’s nuclear capabilities to the West. This week, North Korea’s leader Kim Jong Un supervised a live-fire exercise of nuclear-capable multiple rocket launchers designed to target South Korea’s capital — just the latest in a flurry of recent nuclear-capable missile tests.

Most disturbing, however, has been the repeated use of chemical weapons on the battlefields of Ukraine by Russian forces and in clandestine targeted assassinations by Russian and North Korean agents.

In today’s post, the Mad Scientist Laboratory continues its exploration of the Operational Environment on behalf of the Army, examining the role WMD play in today’s Operational Environment and ten years hence across the competition continuum — “Combatants are increasingly likely to employ prohibited weapons to gain tactical advantages and mitigate weaknesses, especially to break stalemates and level perceived adversarial overmatch capabilities” — Read on!]

WMD Threat Today

Per the recently published Office of the Director for National Intelligence’s Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community:

“The expansion of nuclear weapons stockpiles and their delivery systems, coupled with increasing regional conflicts involving nuclear weapons states, pose a significant challenge to global efforts to prevent the spread and use of nuclear weapons…. The use of chemical weapons, particularly in situations other than state-on-state military operations, could increase in the near future…. Current biological agents and rapidly advancing biotechnology underscore the diverse and dynamic nature of deliberate biological threats.” [i]

“The expansion of nuclear weapons stockpiles and their delivery systems, coupled with increasing regional conflicts involving nuclear weapons states, pose a significant challenge to global efforts to prevent the spread and use of nuclear weapons…. The use of chemical weapons, particularly in situations other than state-on-state military operations, could increase in the near future…. Current biological agents and rapidly advancing biotechnology underscore the diverse and dynamic nature of deliberate biological threats.” [i]

The following recent media and government reports highlight specific contemporary WMD threats:

Iran is reportedly able to produce enough weapons-grade enriched uranium for a nuclear weapon in one week, using only a fraction of its 60 percent enriched uranium.[ii]

During recent submarine-launched cruise missile tests in late January 2024, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un reiterated his goal of building a nuclear-armed navy to counter what he described as growing external threats.[iii] ODNI reported that North Korea also continues to threaten to conduct its seventh nuclear test.[iv]

The most likely WMD threat our Soldiers will face in today’s Operational Environment are Chemical Weapons. Ukrainian Armed Forces have recorded 626 instances of Russian forces using munitions containing toxic chemicals, including 51 cases in January 2024 alone. Russia’s use of chemical agents is on the rise in Ukraine, with approximately ten cases reported every day. The UAF General Staff reported Russia most often used chemical grenades (e.g., K-51s and RGDs), dropped from Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). Russia also reportedly uses Improved Explosive Devices (IEDs) with irritants added and artillery shells loaded with hazardous chemicals.[v] Chemical agents employed by Russia include Chloropicrin, a strong irritant developed for use by Czarist Russia as poison gas during World War I, and tear gas (CS) variants: 2-Chlorobenzylidene Malononitrile and Cheryomukha. Russia’s battlefield use of chemical agents includes degrading troop effectiveness in confined defensive positions (e.g., buildings, tunnels, and trenches), and flushing troops from these defenses to expose them to kinetic fires.

As reported by ODNI:

“During the past decade, state and non-state actors have used chemical warfare agents in a range of scenarios, including the Syrian military’s use of chlorine and sarin against opposition groups and civilians, and North Korea’s and Russia’s use of chemical agents in targeted killings. More state actors could use chemicals in operations against dissidents, defectors, and other perceived enemies of the state; protestors under the guise of quelling domestic unrest; or against their own civilian or refugee populations.” [vi]

Weapons of mass destruction and effect, whether nuclear, radiological, chemical, or biological, will continue to figure prominently across the competition, crisis, and conflict spectrum. Combatants are increasingly likely  to employ prohibited weapons to gain tactical advantages and mitigate weaknesses, especially to break stalemates and level perceived adversarial overmatch capabilities. The U.S. Army should prepare to encounter WMDs on the 21st Century battlefield.

to employ prohibited weapons to gain tactical advantages and mitigate weaknesses, especially to break stalemates and level perceived adversarial overmatch capabilities. The U.S. Army should prepare to encounter WMDs on the 21st Century battlefield.

WMD Threat in 2033

The U.S. will remain the most powerful conventional military force in 2033, although China will have some ability to challenge the U.S. in the Indo-Pacific. Threat actors will increasingly seek unconventional capabilities to offset U.S. conventional military superiority.

The world’s nuclear balance will be increasingly complex and unstable through 2033. In 2033, Russia will remain the most heavily nuclear-armed country. China will be approaching peer-status with nuclear weapons. North Korea will continue to be a regional nuclear threat with limited global capability. Iran will still hedge nuclear capabilities and may have developed a nuclear weapon.

Russia’s arsenal includes nearly 6,000 strategic and non-strategic nuclear warheads, 4,500 of which are likely operationally ready.[vii] Additionally, Russia has been working to modernize its nuclear forces through development of hypersonic missiles and glide-vehicles, nuclear-powered cruise missiles, autonomous underwater systems, and multiple-warhead capable intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs).[viii] Russian defense doctrine relies upon limited nuclear strike capability to compensate for conventional inadequacies,[ix] including the threat or use of limited nuclear strikes to compel an enemy to end military operations.[x]

China is also expanding and modernizing its nuclear arsenal. By 2033, China will have more than 1000 nuclear warheads,[xi] persistent ballistic missile submarine patrol capacity, dedicated nuclear bombers,[xii] and hundreds of hardened ICBM facilities.[xiii] These improvements will allow China to shift from its historic assured retaliation nuclear posture to an asymmetric escalation posture that could include first use.[xiv]

Nuclear-armed aggressor states will be tempted to use nuclear blackmail to shield conventional actions, particularly if Russia succeeds in Ukraine. Countries without nuclear weapons, especially nuclear hedgers, will be increasingly likely to develop nuclear weapons. Those most likely include countries facing proximate conventional threats without credible, binding international security agreements. With the U.S. facing two nuclear near-peer adversaries, nuclear deterrence will resemble a three-body problem, with unpredictable third order effects.

Rogue actors without the resources and technical capability for nuclear weapons will continue chemical weapons programs. Advances in science, handling, and manufacturing will facilitate development of chemical weapons and delivery platforms. Production and storage capacity will remain a limiting factor. Nation states may be able to deter chemical weapons employment through conventional power, but civilian populations will remain vulnerable to oppressive regimes and terrorist actors.

Complementary advances in biological sciences, information science, and nanotechnology will increase the likelihood of customized bioweapon development. Tailored weapons, exploiting ubiquitous genomic data to target specific groups or individuals, will be within reach, if not in production. Advances in biotechnology are assessed as increasing the risk of the U.S. and its allies’ forces being confronted with a genetically-modified biological weapon by 2030.[xv] Per ODNI, rapid advances in dual-use technology, including bioinformatics, synthetic biology, nanotechnology, and genomic editing, could enable development of novel biological threats.[xvi] However, a recent RAND Corporation experiment — with 12 ‘red teams’ with varying operational, biological, and Large Language Model (e.g., Artificial Intelligence) experience — concluded that ChatGPT-like methods (versus standard online search engines) did not provide any substantial advantage in generating a biological attack. [xvii]

Russia and North Korea have maintained bioweapons programs for decades, in flagrant violation of their treaty requirements. Both countries continue to research biological agents and delivery systems,[xviii] with no indications they will abandon these programs. There is no proof China and Iran have active bioweapons programs, but neither country has presented satisfactory evidence of dismantling legacy

Russia and North Korea have maintained bioweapons programs for decades, in flagrant violation of their treaty requirements. Both countries continue to research biological agents and delivery systems,[xviii] with no indications they will abandon these programs. There is no proof China and Iran have active bioweapons programs, but neither country has presented satisfactory evidence of dismantling legacy  programs. Both countries actively research dual-use programs at state-affiliated institutions.[xix] By 2033, Russia and North Korea will remain the most significant bioweapons actors, while the PRC and Iran will likely be able to transition rapidly to offensive programs. The possibility of a bioweapon falling into the hands of a non-state actor will remain real. However, the COVID-19 epidemic highlighted the increased vulnerability of developing governments to biological threats. Consequently, even nefarious actors will have strong incentives to ensure bioweapon security.

programs. Both countries actively research dual-use programs at state-affiliated institutions.[xix] By 2033, Russia and North Korea will remain the most significant bioweapons actors, while the PRC and Iran will likely be able to transition rapidly to offensive programs. The possibility of a bioweapon falling into the hands of a non-state actor will remain real. However, the COVID-19 epidemic highlighted the increased vulnerability of developing governments to biological threats. Consequently, even nefarious actors will have strong incentives to ensure bioweapon security.

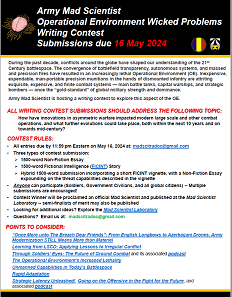

>>>>REMINDER: Army Mad Scientist wants to crowdsource your thoughts on asymmetric warfare — check out our Operational Environment Wicked Problems Writing Contest.

All entries must address the following topic:

How have innovations in asymmetric warfare impacted modern large scale and other combat operations, and what further evolutions could take place, both within the next 10 years and on towards mid-century?

We are accepting three types of submissions:

-

-

- 1500-word Non-Fiction Essay

-

-

-

- 1500-word Fictional Intelligence (FICINT) Story

-

-

-

- Hybrid 1500-word submission incorporating a short FICINT vignette, with a Non-Fiction Essay expounding on the threat capabilities described in the vignette

-

Anyone can participate (Soldiers, Government Civilians, and all global citizens) — Multiple submissions are encouraged!

Anyone can participate (Soldiers, Government Civilians, and all global citizens) — Multiple submissions are encouraged!

All entries are due NLT 11:59 pm Eastern on May 16, 2024 at: madscitradoc@gmail.com

Click here for additional information on this contest — we look forward to your participation!

If you enjoyed today’s post, check out the first three in this Operational Environment series:

Unmanned Capabilities in Today’s Battlespace

The Operational Environment’s Increased Lethality

… as well as the TRADOC G-2‘s Operational Environment Enterprise web page, brimming with information on the Operational Environment and how our adversaries fight…

… and the following related Mad Scientist Laboratory posts:

The Resurgent Scourge of Chemical Weapons, by Ian Sullivan

The Outsized Fear of Small Nuclear Threats, by proclaimed Mad Scientist Dr. James Giordano and Bob Williams

A New Age of Terror: New Mass Casualty Terrorism Threats and A New Age of Terror: The Future of CBRN Terrorism by proclaimed Mad Scientist Zak Kallenborn

Dead Deer, and Mad Cows, and Humans (?) … Oh My! by proclaimed Mad Scientists LtCol Jennifer Snow and Dr. James Giordano, and Joseph DeFranco

Heeding Breaches in Biosecurity: Navigating the New Normality of the Post-COVID Future, by John Wallbank and Dr. James Giordano

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

[i] Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community, Office of the Director of National Intelligence, February 5, 2024, pp. 31-32. https://www.odni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ATA-2024-Unclassified-Report.pdf

[ii] “The Iran Threat Geiger Counter: Reaching Extreme Danger,” Institute for Science and International Security, February 5, 2024, https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/detail/the-iran-threat-geiger-counter-reaching-extreme-danger

[iii] “North Korea says it tested long-range cruise missiles to sharpen attack capabilities,” AP News, January 30, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/north-korea-cruise-missile-long-range-hwasal2-1fa758693c4da59b37880a3aa4cd8891

[iv] ODNI, p. 32.

[v] “Russia’s use of chemical weapons in Ukraine is on the rise,” Ukrayinska Pravda, January 13, 2024, https://news.yahoo.com/russias-chemical-weapons-ukraine-rise-162655114.html?guccounter=1

[vi] ODNI, p. 32.

[vii] Claire Mills, Nuclear Weapons at a Glance: Russia, Commons Library Research Briefing (London: House of Commons Library, March 29, 2022), pp. 13-17.

[viii] Amy F. Woolf, Russia’s Nuclear Weapons: Doctrine, Forces, and Modernization, U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service Report R45861 (Washington, DC: Office of Congressional Information and Publishing, March 1, 2022), pp. 22-29.

[ix] Woolf, pp. 4-9.

[x] Elbridge Colby, “Russia’s Evolving Nuclear Doctrine and Its Implications,” Fondation pour la Recherche Strategique (January 12, 2016), pp. 6-10.

[xi] U.S. Department of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, Annual Report to Congress (2022), https://media.defense.gov/2022/Nov/29/2003122279/-1/-1/1/2022-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF

[xii] United States China Commission, “China’s Nuclear Forces: Moving Beyond a Minimal Deterrent,” Annual Report to Congress (2021), pp. 340-372, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2021-11/Chapter_3_Section_2–Chinas_Nuclear_Forces_Moving_beyond_a_Minimal_Deterrent.pdf

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] Vipin Narang, Nuclear Strategy in the Modern Era: Regional Powers and International Conflict (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), pp. 138-152.

[xv] Dominik Juling, “Future Bioterror and Biowarfare Threats for NATO’s Armed Forces until 2030,” Journal of Advanced Military Studies (JAMS), Marine Corps University Press, Volume 14, Number 1, https://www.usmcu.edu/Outreach/Marine-Corps-University-Press/MCU-Journal/JAMS-vol-14-no-1/Future-Bioterror-and-Biowarfare-Threats/

[xvi] ODNI, p. 32.

[xvii] Christopher A. Mouton, Caleb Lucas, and Ella Guest, “The Operational Risks of AI in Large-Scale Biological Attacks: Results of a Red-Team Study.” Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2024, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2977-2.html

[xviii] Department of State, Adherence to and Compliance with Arms Control, Nonproliferation, and Disarmament Agreements and Commitments (April 2023), https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/13APR23-FINAL-2023-Treaty-Compliance-Report-UNCLASSIFIED-UNSOURCED.pdf

[xix] Ibid.