“America’s adversaries recognize and respect its impressive battlefield capabilities. They don’t want to confront us, at least not yet. How does our Army meet the challenges posed by adversaries who seek to sidestep US battlefield advantages while pursuing their national security objectives during the period 2021-2030? The TRADOC G-2 developed a campaign of learning spanning five months, one drawing on expert opinion from the military, intelligence, rest of government, academic, and industry communities to find answers and provide counsel. These fresh thinkers—young and old, serving and retired—gave their valuable time to provide recommendations not only to the Army, not only to our military, but to all in government and beyond.” — GEN Paul E. Funk II. CG, TRADOC, from his Foreword to Is Ours a Nation at War?

[Editor’s Note: Last year, the TRADOC G-2 facilitated a campaign of learning on behalf of the CG to address how the Operational Environment was being affected by the Global COVID-19 Pandemic and how our adversaries are evolving to bypass our strengths and realize their objectives without fighting. The resulting Proceedings comprehensively document the existing and evolving threats posed by China and Russia, detail U.S. vulnerabilities, and provide specific recommendations (organized by Doctrine, Organization, Training, Materiel, Leadership and education, Personnel, Facilities, and Policy [DOTMLPF-P]) to redress these vulnerabilities — a link to this comprehensive report may be found below. Today’s post excerpts Chapter 2 of these Proceedings, describing the Operational Environment and the changing character of warfare — Enjoy!]

The U.S. Army and its partners confront an operational environment in which select state threats work to perfect ways of achieving national objectives without having to engage the United States in armed conflict. Yet at the same time, economic and other ties with these threats vary from virtually nonexistent to extensive. U.S. leaders must incorporate these interdependencies into any strategies, recognizing both inherent opportunities and challenges. The operational environment is made the more complex as diplomatic, economic, and cultural tools find company in new, potentially existential threats, heretofore unseen avenues for psychological manipulation of populations among them. This state of affairs has a complement in which nonstate actors and states with less robust economies can access capabilities previously reserved for heartier national budgets and development processes.

The U.S. Army and its partners confront an operational environment in which select state threats work to perfect ways of achieving national objectives without having to engage the United States in armed conflict. Yet at the same time, economic and other ties with these threats vary from virtually nonexistent to extensive. U.S. leaders must incorporate these interdependencies into any strategies, recognizing both inherent opportunities and challenges. The operational environment is made the more complex as diplomatic, economic, and cultural tools find company in new, potentially existential threats, heretofore unseen avenues for psychological manipulation of populations among them. This state of affairs has a complement in which nonstate actors and states with less robust economies can access capabilities previously reserved for heartier national budgets and development processes.

Countering this multitude of threat types is tougher for the US than for our adversaries who frequently have the advantage of being able to focus on a single, primary foe: us. Expert panel member John Pulju compared the current period to that in the aftermath of World War II during which the emergence of a new strategic challenge—strategic nuclear weapons—did not obviate the requirement to be vigilant and capable in the conventional warfare arena. The struggle  to find an effective yet affordable deterrence to those weapons was characterized by vigorous debate, trial and error, inter-service (and at time intra-service) tensions, and the building of some of history’s strongest and longest-lasting alliances.

to find an effective yet affordable deterrence to those weapons was characterized by vigorous debate, trial and error, inter-service (and at time intra-service) tensions, and the building of some of history’s strongest and longest-lasting alliances.

The United States found itself the world’s hegemon when the Cold War ended. That status was of short duration yet one sufficiently long for many to conclude that ours is a force undefeatable on the battlefield. Several expert panel members and other participants in the Campaign of Learning find such a  conclusion smacks of hubris. One likened the situation to that of once market leaders like Polaroid and US automobile manufacturers in the commercial world. But the challenge is tougher yet for the US. Unlike in those years immediately following WWII, the United States did not initially dominate in fields of emerging consequence. These are contested spaces, ones in which adversaries sometimes lead and are already refining their capabilities by testing them in locations such as Ukraine, India, and the Baltic states. China, Russia, and other parties constantly exercise information operations to undermine the appeal of democracy generally and that in the US in particular, portraying us as a nation whose social, political, and economic divisions are proof of democracy’s inherent weakness as a form of government.

conclusion smacks of hubris. One likened the situation to that of once market leaders like Polaroid and US automobile manufacturers in the commercial world. But the challenge is tougher yet for the US. Unlike in those years immediately following WWII, the United States did not initially dominate in fields of emerging consequence. These are contested spaces, ones in which adversaries sometimes lead and are already refining their capabilities by testing them in locations such as Ukraine, India, and the Baltic states. China, Russia, and other parties constantly exercise information operations to undermine the appeal of democracy generally and that in the US in particular, portraying us as a nation whose social, political, and economic divisions are proof of democracy’s inherent weakness as a form of government.

Recent cyberattacks such as those perpetrated through SolarWinds and against the Colonial Pipeline demonstrate a willingness to employ these capabilities either directly, via surrogates, or through benign tolerance of criminal elements (who could be viewed as another form of surrogate). They represent a fundamental difference from the threats posed during the Cold War. Attacks with nuclear weapons were not a viable option. Complete defense should one side have decided to use these weapons was virtually impossible; even partial failure would have meant devastating results for all adversaries. Deterrence was the only viable option.

Recent cyberattacks such as those perpetrated through SolarWinds and against the Colonial Pipeline demonstrate a willingness to employ these capabilities either directly, via surrogates, or through benign tolerance of criminal elements (who could be viewed as another form of surrogate). They represent a fundamental difference from the threats posed during the Cold War. Attacks with nuclear weapons were not a viable option. Complete defense should one side have decided to use these weapons was virtually impossible; even partial failure would have meant devastating results for all adversaries. Deterrence was the only viable option.

Conditions are far different today. While complete defense against cyber and information attacks is impossible now as it was then, effective forms of deterrence remain elusive. The consequences of future assaults will sometimes be less obvious than those seen thus far. Affected computer algorithms may result in friendly forces receiving wrong or misguiding information or weapons striking incorrect targets for seemingly inexplicable reasons. The immediate battlefield effects might be significant; the longer-lasting undermining of trust in warfighting systems could be paralyzing. Unlike with nuclear weapons, such characteristics make their use attractive rather than unthinkable.

Conditions are far different today. While complete defense against cyber and information attacks is impossible now as it was then, effective forms of deterrence remain elusive. The consequences of future assaults will sometimes be less obvious than those seen thus far. Affected computer algorithms may result in friendly forces receiving wrong or misguiding information or weapons striking incorrect targets for seemingly inexplicable reasons. The immediate battlefield effects might be significant; the longer-lasting undermining of trust in warfighting systems could be paralyzing. Unlike with nuclear weapons, such characteristics make their use attractive rather than unthinkable.

These evolutions are changing the nature of warfare. With notable exceptions, most English definitions for “war” require opposing sides to engage in armed conflict. Even that seemingly sharp delineation permits considerable gray area both in terms of legal definitions (Was the 1950-1953 conflict in Korea a war or a police action?) and broader understanding. What of the operational environment today? Lieutenant General Dennis A. Crall proposed that our understanding of what constitutes warfare should be considerably broader than that traditionally accepted:

Fighting looks different today. It disarms people when they think that somehow it’s not a fight. Many of the briefs that I’ve seen in the Pentagon start with this idea that we push our adversary into the competition space to avoid conflict. We don’t need to push them there; that is exactly the space they want to be in…. They routinely rob our defense industrial base. They cut off years of research and development and save billions of dollars in technology development and fees. They have unprecedented access into our infrastructure. Why would they possibly want to change? I equate this to sending my kids to their room when they were younger. That’s where they wanted to be! That’s where all their stuff was. Our adversary seems to be operating in that space and we consider that not warfighting. We need to recognize that it is warfighting. It’s not the fight that’s coming; it’s the fight we’re already in.

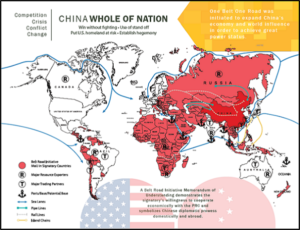

Adversaries maneuvering in these other-than-combat realms means wars “will be sneakier,” in the words of one speaker during the Campaign of Learning’s first webinar. Deniability could be more valuable than firepower even as much of this maneuvering below the threshold of armed conflict is evident to all. China’s aggressive promotion of its national interests via the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) demonstrates adroitness in this regard—creative use of lending that sidesteps internationally accepted practices, imposing debt that hamstrings any successor government’s efforts to undo unfavorable agreements put in place by its predecessor, employment information campaigns exaggerating benefits while ignoring obvious shortfalls of such commercial agreements—these comprise but a miniscule sample of past and ongoing practices.

Russia’s seizure of Crimea and other portions of eastern Ukraine is a sterling exemplar of maneuver below a threshold that precipitates armed response. Use of surrogate militias, deception operations, and forms of attack for which NATO was largely unprepared (e.g., cyberattacks and economic coercion) left Russia threatened only with sanctions and diplomatic pressure deemed acceptable for the objectives achieved. There is good reason to believe that they will observe, learn, and adapt their approaches for using this broader understanding of warfare.

Author David Kilcullen believes such could be the case with biological warfare. Having seen the effects of COVID-19 on U.S. Navy ship crews, it is logical to conclude that the attractiveness of employing biological agents against such “captive” targets has been noted for possible future use. The debates surrounding the source of COVID-19 demonstrate how difficult it could be to definitively identify a perpetrator much less cultivate the domestic and international support needed to employ armed force in response. That such attacks could cripple vital capabilities while remaining largely or entirely nonlethal would further promote a reaction remaining below the threshold of armed response.

If you enjoyed this post, please read the comprehensive publication Is Ours a Nation at War? Proceedings for the TRADOC G-2 2021 “Role of America’s Army in National Defense, 2021-2030” Campaign of Learning here, published by our colleagues at the Center for Army Lessons Learned (CALL)

… and check out the following related content:

The Operational Environment (2021-2030): Great Power Competition, Crisis, and Conflict, the entire document from which that post was excerpted, and the TRADOC G-2’s Threats to 2030 video addressing the challenges facing the U.S. Army in the current OE (i.e., now to 2030)

Sub-threshold Maneuver and the Flanking of U.S. National Security, by Dr. Russell Glenn

The Erosion of National Will – Implications for the Future Strategist, by Dr. Nick Marsella

China and Russia: Achieving Decision Dominance and Information Advantage, by Ian Sullivan; How Russia Fights with its associated podcast; and How China Fights with its associated podcast

In the Crosshairs: U.S. Homeland Infrastructure Threats, The Future of War is Cyber! by CPT Casey Igo and CPT Christian Turley, and Why the Next “Cuban Missile Crisis” Might Not End Well: Cyberwar and Nuclear Crisis Management by Dr. Stephen J. Cimbala

Hybrid Threats and Liminal Warfare and associated podcast, with proclaimed Mad Scientist Dr. David Kilcullen