[Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist Laboratory is pleased to publish the latest post in our “Contagion” series, co-authored by Vikram Venkatram and proclaimed Mad Scientist and returning guest blogger Dr. James Giordano. Recognizing the scope and breadth of the COVID-19 pandemic’s trail of disruption around the globe, Mr. Venkatram and Dr. Giordano explore the proactive and preventive measures taken by three nations: Singapore, South Korea, and Germany, that enabled their respective populations to “beat the odds” and weather this viral onslaught markedly better than the rest of the international community.

Per Dr. Gerald Parker, Director of the Pandemic and Biosecurity Policy Program, The Bush School of Government and Public Service, Texas A&M University, there are five phases associated with the pandemic, with the fifth being preparing for the next pandemic. “Unfortunately, we’ve entered a period where emerging infectious diseases are increasing with alarming frequency” — SARS, MERS, the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, Ebola, Zika, and now COVID-19. Enhanced bio-surveillance and security measures are but two of the more obvious requirements that will be forthcoming from a post COVID-19 Global Pandemic commission. The Department of Defense and its constituent Services are likely to assume additional missions, and with that, face re-prioritizations in funding. Read on!]

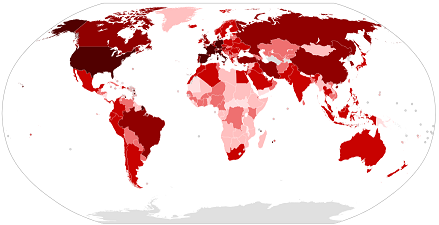

The current COVID-19 pandemic has drastically affected the lives of the majority of United States’ citizens, destabilized healthcare systems, severely impacted the  economy, and revealed vulnerabilities in pandemic preparedness. To be sure, this pandemic can be characterized as a biosecurity threat, not only to the US, but globally. What we find most disconcerting are domestic failures to heed the history of previous public health crises (such as the SARS and MERS epidemics in Asia, Ebola in Africa, and the H1N1 crisis), take advantage of existing pandemic preparedness infrastructure, and/or acknowledge and act upon iterative intelligence information about the occurrence, spread, and gravity of the disease.

economy, and revealed vulnerabilities in pandemic preparedness. To be sure, this pandemic can be characterized as a biosecurity threat, not only to the US, but globally. What we find most disconcerting are domestic failures to heed the history of previous public health crises (such as the SARS and MERS epidemics in Asia, Ebola in Africa, and the H1N1 crisis), take advantage of existing pandemic preparedness infrastructure, and/or acknowledge and act upon iterative intelligence information about the occurrence, spread, and gravity of the disease.

It is notable that other countries have been far more effective – and efficient – in preparedness and response. While it may be useful to view China’s efforts in this regard, direct comparison may be of little value, as it is irrational to consider open liberal democracies imitating the political systems of authoritarian societies, regardless of how successful their pandemic controls. However, there are open societies that have demonstrated significant public health preparedness and successful responses, including Singapore, South Korea, and Germany. Although the specific methods employed by these nations differ, each and all have limited the spread and mortality of COVID-19. In this light, we opine that lessons learned from these cases could be useful to improving US biosecurity policy, infrastructure, and functions.

Singapore:

Singaporean society may be regarded as less “open” than that of the US. Nevertheless, the country’s response to COVID-19 has been effective and admirable; as of 10 April 2020, there were only 875 active cases, and have been only 7 deaths in total. Singapore experienced an outbreak of SARS in 2003, a disease caused by a coronavirus similar to the one that causes COVID-19. The lessons learned from that outbreak likely affected the response to the current crisis.  Singaporean governmental and social agencies reacted to China’s initial announcement about the virus with considerable rapidity: releasing a preliminary case definition within days and warning health workers to be vigilant for any suspected cases. Contact tracing was emphasized, large events were cancelled, and body temperature/febrile screenings were instituted. Those who were found to be in contact with individuals infected with COVID-19 were placed in quarantine, with stringent punishment for those violating isolation orders (including high fines and incarceration). Singapore has engaged extensive use of both its military and internal surveillance capabilities. Military forces have contributed to mask distribution, phone calls for contact tracing, and monitoring of travelers at the airport, working in 8-hour shifts around the clock. Those who have interacted with a COVID-19 patient are placed under surveillance, and are contacted by telephone either once or thrice daily (depending on the closeness of contact). In addition, monitoring has been expanded to patients with pneumonia or influenza-like symptoms.

Singaporean governmental and social agencies reacted to China’s initial announcement about the virus with considerable rapidity: releasing a preliminary case definition within days and warning health workers to be vigilant for any suspected cases. Contact tracing was emphasized, large events were cancelled, and body temperature/febrile screenings were instituted. Those who were found to be in contact with individuals infected with COVID-19 were placed in quarantine, with stringent punishment for those violating isolation orders (including high fines and incarceration). Singapore has engaged extensive use of both its military and internal surveillance capabilities. Military forces have contributed to mask distribution, phone calls for contact tracing, and monitoring of travelers at the airport, working in 8-hour shifts around the clock. Those who have interacted with a COVID-19 patient are placed under surveillance, and are contacted by telephone either once or thrice daily (depending on the closeness of contact). In addition, monitoring has been expanded to patients with pneumonia or influenza-like symptoms.

South Korea:

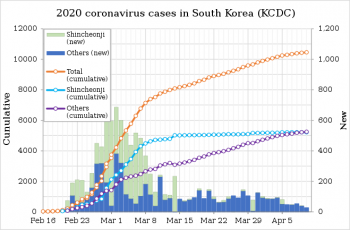

The South Korean response to COVID-19 has also been effective, but unlike that in Singapore, it de-emphasized the use of the military. As in Singapore, South Korean government agencies, commercial entities, and citizens were primed to respond to COVID-19 due to prior experiences with the SARS epidemic of 2003 and the MERS epidemic of 2015 (which did not impact Singapore). Due to social norms that differ from the US, South Korea had masks readily and publicly available, and recommended their widespread use throughout the population. In so doing, South Korea faced its own mask shortage; but was able to anticipate the situation, expand production of masks, maintain public access, and continue to effectively distribute resources. Additionally, while the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) chose to ignore World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations regarding testing and instead tried to develop its own test, the South Korean government began production of test kits using the WHO template within a week of the initial announcement of the disease from China. Policy reform instituted in the aftermath of MERS enabled the South Korean to rapidly approve tests during an emergency.

This allowed South Korea to test more of its citizens than any other country: with 10,000 people being tested, and 100,000 tests being produced each day. Furthermore, South Korean President Moon offered to provide millions of test kits to the US in return for reduced pressure for military burden-sharing during Special Measures Agreement negotiations. The Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has maintained ongoing interaction with the citizenry, holding two press conferences daily, and the country has used technology to contact, trace, and communicate, as cellphones deliver emergency alerts, and websites and apps track and publish the movements of those infected. Thus, sans extensive military intervention and intrusion to the lives of its citizens, South Korea has been able to effectively incorporate lessons learned from prior epidemics, and act quickly and efficiently to protect its population from COVID-19.

Germany:

Germany has had more limited access to tests than South Korea, and has used its military less than Singapore. In contrast, the country has utilized a decentralized approach to its COVID-19 response, allowing each of its 16 länder (states) to develop response-planning and make decisions for testing and containment. Germany’s Robert Koch Institute, its federal agency focused on disease control, is not equivalent to the CDC, which centrally controls the US’s approach(es) to testing and in this way may restrict other labs from performing tests. Rather, each German state has control over its own healthcare system, enabling each of them to make time-sensitive and nimble choices about test production, distribution, and utilization. The COVID-19 mortality rate in Germany has been very low — approximately 1.2% — despite the occurrence of more than 73,000 cases nationally.

Germany has had more limited access to tests than South Korea, and has used its military less than Singapore. In contrast, the country has utilized a decentralized approach to its COVID-19 response, allowing each of its 16 länder (states) to develop response-planning and make decisions for testing and containment. Germany’s Robert Koch Institute, its federal agency focused on disease control, is not equivalent to the CDC, which centrally controls the US’s approach(es) to testing and in this way may restrict other labs from performing tests. Rather, each German state has control over its own healthcare system, enabling each of them to make time-sensitive and nimble choices about test production, distribution, and utilization. The COVID-19 mortality rate in Germany has been very low — approximately 1.2% — despite the occurrence of more than 73,000 cases nationally.

Additionally, although testing fewer people than South Korea, Germany has used contact tracing from an early stage to limit the spread of the virus. Initially, Germany used testing criteria similar to those employed in Italy, one of the countries hardest hit by the pandemic. Meticulously tracking the contacts of those who tested positive, then testing and quarantining them effectively slowed the disease’s spread. Germany’s use of expanded testing criteria, mandatory social distancing, federal states’ restrictions of gatherings of more than two people outside the home, and the fact that Germany has a greater number of intensive care beds and ventilators than any other European country, have all been instrumental to the success of pandemic response. Moreover, to address the dilemma of social distancing measures for public health while sustaining the economy, Germany has adopted drastic economic measures, including liquidity assistance, unlimited cash transfers, and exercised a willingness to incur debt in order to mitigate the financial and corporate harm caused by COVID-19.

Of course, Singapore, South Korea, and Germany are far smaller than the US, both in geographical size and population. The logistics and scope of the biosecurity problem are undoubtedly harder to deal with in a nation as large as the US. Yet, although these countries may be small, inspiration should be taken from their responses, as useful and of value to both national and local preparedness. The diverse, but similar responses all emphasize readiness, decisiveness, contact tracing, availability of resources, and a willingness to enact change in – and to protect – peoples’ lives, regardless of political position or partisan consequences.

Of course, Singapore, South Korea, and Germany are far smaller than the US, both in geographical size and population. The logistics and scope of the biosecurity problem are undoubtedly harder to deal with in a nation as large as the US. Yet, although these countries may be small, inspiration should be taken from their responses, as useful and of value to both national and local preparedness. The diverse, but similar responses all emphasize readiness, decisiveness, contact tracing, availability of resources, and a willingness to enact change in – and to protect – peoples’ lives, regardless of political position or partisan consequences.

The aforementioned cases demonstrate that preparedness and quick, decisive responses to COVID-19 – and/or any other biothreat – are necessary for effective and efficient biosecurity, regardless of particular distinctions in approach. The US does not need to close its society, advance authoritarianism, or curtail individual freedoms in the long-term in order to be prepared for biosecurity threats similar to this global pandemic. We opine that what is needed is a whole-of-government action to conjoin the resources and services necessary for preparedness and response. But while necessary, we believe that this by itself is insufficient, and call for a coordinated whole-of-nation approach that involves – and supports – the infrastructures and functions of the governmental, public, and commercial sectors to meet such threats, lessen harms, and sustain stability and safety.

If you enjoyed this post, check out the preceding ones in this series:

Contagion: COVID-19’s impact on the Operational Environment (Part 1), by Chris Elles

Contagion: COVID-19’s impact on the Operational Environment (Part 2), by Kat Cassedy

… as well as the biothreat piece Dead Deer, and Mad Cows, and Humans (?) … Oh My! by proclaimed Mad Scientists LtCol Jennifer Snow and Dr. James Giordano, and Joseph DeFranco.

Vikram Venkatram is a student at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, where his studies focus on Science, Technology, and International Affairs, with a concentration in Science, Technology, and Security, and a minor in Biology, and is pursuing graduate work through the accelerated BSFS/Security Studies M.A. program. He is a scholar of the O’Neill-Pellegrino Program in Science and Global Health Law and Policy of the Georgetown University Medical Center. His ongoing work focuses upon biosecurity and biohazard response, dual-use neuroscience and technology and global surveillance and policy. His work has been featured by the Strategic Multi-Layer Assessment Group, Joint Staff, Pentagon.

Mad Scientist James Giordano, PhD is Professor in the Departments of Neurology and Biochemistry, Chief of the Neuroethics Studies Program, Co-director of the O’Neill-Pellegrino Program in Science and Global Law and Policy, and Special Projects’ Advisor to the Brain Bank at Georgetown University Medical Center. He is Senior Fellow of the Project on Biosecurity and Ethics at the US Naval War College, Newport, RI; and consulting bioethicist to the US Defense Medical Ethics Committee, currently addressing biosecurity and biomedical response capabilities to mitigate the COVID-19 crisis. As well, he chairs the Neuroethics Subprogram of the IEEE Brain Initiative; is a Fellow of the Defense Operations Cognitive Science section, SMA Branch, Joint Staff, Pentagon; and is an appointed member of the Neuroethics, Legal and Social Issues Advisory Panel of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). He has previously served as Donovan Senior Fellow for Biowarfare and Biosecurity at US Special Operations Command (USSOCOM); as Research Fellow and Task Leader of the EU-Human Brain Project Sub-Program on Dual-Use Brain Science; as an appointed member of the Department of Health and Human Services Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections (SACHRP); and as senior consultant to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development Working Group on Dual-Use of International Neurotechnology.

A Fulbright scholar, Dr. Giordano was awarded the JW Fulbright Visiting Professorship of Neuroscience and Neuroethics at the Ludwig-Maximilians University, Munich, GER, and currently is Distinguished Visiting Professor of Brain Science, Health Promotions, and Ethics at the Coburg University of Applied Sciences, Coburg, GER. He was previously an International Fellow of the Centre for Neuroethics at the University of Oxford, UK.

Prof. Giordano is the author of over 300 papers, 7 books, 21 book chapters, and 16 government white papers on brain science, national defense and ethics, his book, Neurotechnology in National Security and Defense: Practical Considerations, Neuroethical Concerns (2015, CRC Press) is widely regarded and used as a definitive work on the topic. In recognition of his achievements he was elected to the European Academy of Science and Arts, and named an Overseas Fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine (UK).

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or the Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

Concur with the whole of nation approach; except neither of the three countries identified has had the “blame game” occurring for years which has effectively rendered an approach like their’s moot.

We can see the ongoing “look how bad…” approach, diversion of facts, mass shotgunning of statistics and charts (which the average Joe has no idea what it means besides the other side” screwed it up).

Additionally, much like the continued comparisons of ‘look how good Sweden did it!” use of death and infection numbers aren’t logically utilized; specifically, the lack ofcapita per comparisons. In the case of Sweden, if one is to compare them to the US per capita, then Sweden would have the equivalent of 400,000 dead as compared per capita to the US–but it doesn’t and that’s the problem.