[Editor’s Note: As stated previously here in the Mad Scientist Laboratory, the nature of war remains inherently humanistic in the Future Operational Environment. Today’s post by guest blogger COL James K. Greer (USA-Ret.) calls on us to stop envisioning Artificial Intelligence (AI) as a separate and distinct end state (oftentimes in competition with humanity) and to instead focus on preparing for future connected competitions and wars.]

The possibilities and challenges for future security, military operations, and warfare associated with advancements in AI are proposed and discussed with ever-increasing frequency, both within formal defense establishments and informally among national security professionals and stakeholders. One is confronted with a myriad of alternative futures, including everything from a humanity-killing variation of Terminator’s SkyNet to uncontrolled warfare ala WarGames to Deep Learning used to enhance existing military processes and operations. And of course legal and ethical issues surrounding the military use of AI abound.

The possibilities and challenges for future security, military operations, and warfare associated with advancements in AI are proposed and discussed with ever-increasing frequency, both within formal defense establishments and informally among national security professionals and stakeholders. One is confronted with a myriad of alternative futures, including everything from a humanity-killing variation of Terminator’s SkyNet to uncontrolled warfare ala WarGames to Deep Learning used to enhance existing military processes and operations. And of course legal and ethical issues surrounding the military use of AI abound.

Yet in most discussions of the military applications of AI and its use in warfare, we have a blind spot in our thinking about technological progress toward the future. That blind spot is that we think about AI largely as disconnected from humans and the human brain. Rather than thinking about AI-enabled systems as connected to humans, we think about them as parallel processes. We talk about human-in-the loop or human-on-the-loop largely in terms of the control over autonomous systems, rather than comprehensive connection to and interaction with those systems.

But even while significant progress is being made in the development of AI, almost no attention is paid to the military implications of advances in human connectivity. Experiments have already been conducted connecting the human brain directly to the internet, which of course connects the human mind not only to the Internet of Things (IoT), but potentially to every computer  and AI device in the world. Such connections will be enabled by a chip in the brain that provides connectivity while enabling humans to perform all normal functions, including all those associated with warfare (as envisioned by John Scalzi’s BrainPal in “Old Man’s War”).

and AI device in the world. Such connections will be enabled by a chip in the brain that provides connectivity while enabling humans to perform all normal functions, including all those associated with warfare (as envisioned by John Scalzi’s BrainPal in “Old Man’s War”).

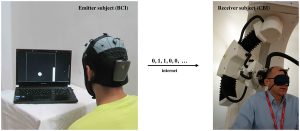

Moreover, experiments in connecting human brains to each other are ongoing. Brain-to-brain connectivity has occurred in a controlled setting enabled by an internet connection. And, in experiments conducted to date, the brain of one human can be used to direct the weapons firing of another human, demonstrating applicability to future warfare. While experimentation in brain-to-internet and brain-to-brain connectivity is not as advanced as the development of AI, it is easy to see that the potential benefits, desirability, and frankly, market forces are likely to accelerate the human side of connectivity development past the AI side.

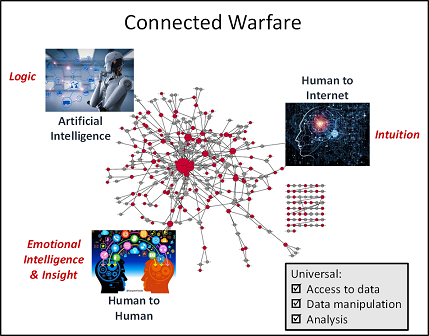

So, when contemplating the future of human activity, of which warfare is unfortunately a central component, we cannot and must not think of AI development and human development as separate, but rather as interconnected. Future warfare will be connected warfare, with implications we must now begin to consider. How would such connected warfare be conducted? How would mission command be exercised between man and machine? What are the leadership implications of the human leader’s brain being connected to those of their subordinates? How will humans manage information for decision-making without being completely overloaded and paralyzed by overwhelming amounts of data? What are the moral, ethical, and legal implications of connected humans in combat, as well as responsibility for the actions of machines to which they are connected? These and thousands of other questions and implications related to policy and operation must be considered.

The power of AI resides not just in that of the individual computer, but in the connection of each computer to literally millions, if not billions, of sensors, servers, computers, and smart devices employing thousands, if not millions, of software programs and apps. The consensus is that at some point the computing and analytic power of AI will surpass that of the individual. And therein lies a major flaw in our thinking about the future. The power of AI may surpass that of a human being, but it won’t surpass the learning, thinking, and decision-making power of connected human beings. When a future human is connected to the internet, that human will have access to the computing power of all AI. But, when that same human is connected to several (in a platoon), or hundreds (on a ship) or thousands (in multiple headquarters) of other humans, then the power of AI will be exceeded by multiple orders of magnitude. The challenge of course is being able to think effectively under those circumstances, with your brain connected to all those sensors, computers, and other humans. This is what Ray Kurzwell terms “hybrid thinking.” Imagine how that is going to change every facet of human life, to include every aspect of warfare, and how everyone in our future defense establishment, uniformed or not, will have to be capable of hybrid thinking.

So, what will the military human bring to warfare that the AI-empowered computer won’t? Certainly, one of the major challenges with AI thus far has been its inability to demonstrate human intuition. AI can replicate some derivative tasks with intuition using what is now called “Artificial Intuition.” These tasks are primarily the intuitive decisions that result from experience: AI generates this experience through some large number of iterations, which is how Goggle’s AlphaGo was able to beat the human world Go champion. Still, this is only a small part of the capacity of humans in terms not only of intuition, but of “insight,” what we call the “light bulb moment”. Humans will also bring emotional intelligence to connected warfare. Emotional intelligence, including aspects such as empathy, loyalty, and courage, are critical in the crucible of war and are not capabilities that machines can provide the Force, not today and perhaps not ever.

Warfare in the future is not going to be conducted by machines, no matter how far AI advances. Warfare will instead be connected human to human, human to internet, and internet to machine in complex, global networks. We cannot know today how such warfare will be conducted or what characteristics and capabilities of future forces will be necessary for victory. What we can do is cease developing AI as if it were something separate and distinct from, and often envisioned in competition with, humanity and instead focus our endeavors and investments in preparing for future connected competitions and wars.

Warfare in the future is not going to be conducted by machines, no matter how far AI advances. Warfare will instead be connected human to human, human to internet, and internet to machine in complex, global networks. We cannot know today how such warfare will be conducted or what characteristics and capabilities of future forces will be necessary for victory. What we can do is cease developing AI as if it were something separate and distinct from, and often envisioned in competition with, humanity and instead focus our endeavors and investments in preparing for future connected competitions and wars.

If you enjoyed this post, please read the following Mad Scientist Laboratory blog posts:

- Takeaways Learned about the Future of the AI Battlefield

- AI Enhancing EI in War

- Ethical Dilemmas of Future Warfare

… and watch Dr. Alexander Kott‘s presentation The Network is the Robot, presented at the Mad Scientist Robotics, Artificial Intelligence, & Autonomy: Visioning Multi Domain Battle in 2030-2050 Conference, at the Georgia Tech Research Institute, 8-9 March 2017, in Atlanta, Georgia.

COL James K. Greer (USA-Ret.) is the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) and Joint Improvised Threat Defeat Organization (JIDO) Integrator at the Combined Arms Command. A former cavalry officer, he served thirty years in the US Army, commanding at all levels from platoon through Brigade. Jim served in operational units in CONUS, Germany, the Balkans and the Middle East. He served in US Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), primarily focused on leader, capabilities and doctrine development. He has significant concept development experience, co-writing concepts for Force XXI, Army After Next and Army Transformation. Jim was the Army representative to OSD-Net assessment 20XX Wargame Series developing concepts OSD and the Joint Staff. He is a former Director of the Army School of Advanced Military Studies (SAMS) and instructor in tactics at West Point. Jim is a veteran of six combat tours in Iraq, Afghanistan, and the Balkans, including serving as Chief of Staff of the Multi-National Security Transition Command – Iraq (MNSTC-I). Since leaving active duty, Jim has led the conduct of research for the Army Research Institute (ARI) and designed, developed and delivered instruction in leadership, strategic foresight, design, and strategic and operational planning. Dr. Greer holds a Doctorate in Education, with his dissertation subject as US Army leader self-development. A graduate of the United States Military Academy, he has a Master’s Degree in Education, with a concentration in Psychological Counseling: as well as Masters Degrees in National Security from the National War College and Operational Planning from the School of Advanced Military Studies.

Dr. Greer is correct in that we tend to change our thinking about AI and the interaction AI requires between machines and humans.

Rather than the dystopian future of SkyNet, it is more likely that humans and machines will need to work with each other for the foreseeable future. The machine’s greatest weakness is its lack of sensory perception. Machines cannot and do not perceive of the world around us as we do; they do not have sight, hearing, touch, smell, or taste. Humans must program the machine to accept data from their sensors, fuse the information together, and use the data in a heuristic algorithm to carry out some form of logical reasoning (programmed by humans) to solve problems. Since humans do not necessarily act rationally, our best effort is to program the AI with probability and decision theory so that AI basically tries to optimize the outcome.

An example of the problems faced in the evolution of AI is the DARPA Grand Challenge for 2004 and 2005 which were early tests of the concept of autonomous vehicles. The course required the autonomous system to navigate 150 miles through the Mojave Desert. The systems primarily used lasers as the sensors to identify the terrain in front of them. The returned laser data was converted into 1’s and 0’s, and an algorithm determined whether the terrain in front was “flat” enough to be a road rather than desert. In the 2004 event, no systems made it more than seven miles from the start point. The desert terrain presented challenges that the humans had not anticipated and programmed the system to address. Having a better idea of the challenges and the opportunity to improve the systems’ programming, the next year saw five systems successfully complete the course. As the early programmer Ada Lovelace said, a computer can only do “whatever we know how to order it to perform”.

In more recent DARPA Robotics Challenges, we have observed robots having difficulty in performing simple menial tasks, mainly because they lack the sense of touch and the ability to gauge the pressure that their hands are applying, whether to turn a doorknob or to pick up and hold an egg without crushing it.

I do disagree with Dr. Greer’s statement that AI can’t or won’t surpass the computing and analytic power of a human. AI programmed to analyze Chess or Go games are already there. If we wanted to build a table of perfect moves in chess, we could not even compute the possible number of moves and counter-moves. Such a table has been estimated to require (10 to the 43rd power) entries, and could take (10 to the 90th power) years to calculate (Shannon, 1950). Using heuristics and awesome computer power, AI systems such as IBM’s Deep Blue is already beating grandmasters.

As Dr. Greer predicts, AI and human development will be interconnected. AI brings the computing and analytic power to the fight. However, the AI system’s logical reasoning is only what we program. Humans contribute our senses; that is, we are the ones who must anticipate challenges in the road ahead and program the AI to overcome those obstacles. And as Dr. Greer points out, our ethics and our emotional intelligence are an essential part of the fight that cannot be replicated by AI.

But machines have no reason to fight each other, and AI is not in competition with humanity; historically, the casus belli for our wars have been related to hubris and other human shortcomings. Just as Dr. Greer has asserted, warfare in the future is not going to be conducted by machines alone, no matter how far AI advances.

Reference

Shannon, C.E. (1950). Programming a computer for playing chess. Philosophical magazine, 41(314). http://vision.unipv.it/IA1/ProgrammingaComputerforPlayingChess.pdf.

Agree with most of Mr Cunningham’scommrnts. My point wasn’t that AI couldn’t surpass the thinking of a single human being, but rather can’t surpass the thinking of connected human beings.

The ethical considerations of AI and modern future warfare have not fully been discussed, legalized, decided, ethical review, or enacted.

Modern robotics and AI will definitely complicate the future battlefield as predicted in movies, films, and videogames which are often many years ahead of the current arsenal and inventory of vehicles and equipment capabilities.

Insurgents and terrorists getting their hands on robotics and AI, even if basic to moderate form, could definitely complicate warfare and National Security just because police and fire stations aren’t expanding to accommodate future systems that incorporate AI and robotics. The fire stations’ three garage bays will always be three bays for the coming decades, all filled with rigs with service lives out to 15-20 years. So unless the rigs have AI, drones, robotics, or new features in them, the fire fighters must prepare themselves for the creativeness and ingenuity that AI and robotics pose as future threats in the hands of Lone Wolves and Solo Commandos or networked cells. The same applies to the police departments.

Such AI and robotics foster the growth of Homeland Security centers that build, experiment, foster, and grow robotics and AI for internal and external National Security usages, extrapolating the cutting edge thinking of DARPA and the defense labs in the form of new robotics, AI, drones, and equipment. The moral issue here is that corporate does NOT want to work for government or the military, citing ethical and moral beliefs of the Millennials who grow tired of protracted wars.

If the DoD were to network brains and humans together, would human waves be the answer to future threats? No, not exactly as SKYNET sent robotic TERMINATORS (covered in human flesh) and not human waves of networked soldiers, pure flesh, bone, and blood into battle. Human waves of cyborg soldiers might become mince meat in the face of an AI mechanized army such as the Next Generation Combat Vehicle and Optionally Manned Combat Vehicle with no crew just due to the sheer cannon firepower of those vehicles. Send humans against machines would be a one-sided loss of the humans with no loss to no crews inside.

A Terrorist Cell is a classic example of loosely connected human beings/brains in that dismantling one cell leaves the others. As history has shown, going for the head of the network reveals the other cells, but would chopping off the head kill the snake, or would the headless snake grow a new head?

AI and robotics need to be governed and my suggestion and recommendation is to have a National Emergency Force higher than the faster but poorer local police and fire and below the slower and richer federal Homeland Security and FBI level. Perhaps having State-level AI and robotics Emergency Responders and stations would provide a level of AI and robotics S.W.A.T and EMS rescue above what can be achieved today.