“The most important thing that tends to result in the overall victor is whoever can continue to produce ‘good-enough’ systems. Cheap, durable, and deployable at scale are the most dominant factors for effectiveness in campaign scale wargames.”

[Editor’s Note: Army Mad Scientist continues our “Calling All Wargamers” series of blog posts and podcasts in the run up to our Game On! Wargaming & The Operational Environment Conference, co-hosted with the Georgetown University Wargaming Society, on 6-7 November 2024 — additional information on this event and the link to our registration site may be found at the end of this post (below).

Today’s submission by CPT Spencer D. H. Bates expands on a thread mentioned in last week’s podcast and blog post by Sebastian Bae — “Integrating different types of wargames throughout different echelons allows Soldiers to practice decision making at all levels of their careers.” CPT Bates is a Combat Engineer and Team Leader with Engineer Advisor Team 5521, Bravo Company, 5th Battalion, 5th Security Force Assistance Brigade (SFAB), Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington. He has been an avid wargamer since his early teens, which he ultimately attributes to his pursuing a career in military service — he remains an avid player, reviewer, and organizer of large-scale wargame events. His experiences as a longtime wargamer and company-grade officer resulted in the following insightful contribution to our “Calling All Wargamers” crowdsourcing effort this past spring — Read on to learn what one of today’s generation of rising military leaders has to say about wargaming!]

What are you learning about large scale combat operations?

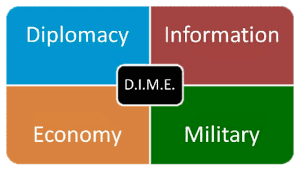

Most conventional wargames do not adequately address strategic concepts. Many if not all tabletop scale wargames focus on tactical-level engagements, but some truly large or expansive rulesets do include operational concepts (rear area, logistic flow, Port of Embarkation [POE] identification, etc.). There are some limited exceptions to this that have strategic dimensions, specifically in games with large ‘campaign operation’ rulesets like Battletech. The point of me saying this is to argue that most conventional wargames, including most grand strategy wargames, do not adequately address the elements of national power – specifically state and economic power.

is to argue that most conventional wargames, including most grand strategy wargames, do not adequately address the elements of national power – specifically state and economic power.

The main concept that overwhelmingly tends to defeat players in large campaign games is economic exhaustion, more so than a more conventional military cause. Disruption of economic infrastructure is almost always the most effective mechanism to reduce or attrit an enemy’s capability to continue to prosecute conflict – specifically attacking specialized centers of production or highly trained civil population centers that produce specialized goods. Forcing the enemy faction to commit to defensive entrenchment of key economic production or seizing key resource nodes that have down-channel production impacts is more important than degrading the battlefield assets – especially those heavily reliant on specialized munitions or large volumes of fuel products. Convoy interdiction (ground or sea) is likewise a highly effective strategy, as forcing the enemy to divert significant combat assets to defend  logistic channels is excellent to both exhaust forces through extended operational cycles as well as force extended operating costs on equipment/maintenance requirements.

logistic channels is excellent to both exhaust forces through extended operational cycles as well as force extended operating costs on equipment/maintenance requirements.

In conclusion, I would argue that the single most effective strategies are almost always centered around economic attacks using conventional and unconventional capabilities. Loss of economic capability directly attrits both military and state power, often creating a death-spiral that ultimately ends with one of the factions no longer being able to meaningfully compete.

What wargames do you find useful for learning about military operations?

This question is multi-faceted because different wargames are good for different things. Wargames vary across two small spectrums, which the ‘community’ broadly refers to as skirmish-campaign and simulationist-abstract. Skirmish games are small scale and can include as few as 2-5 game pieces per side, while campaign scale games can include hundreds or thousands of game pieces. Simulationist games have incredibly detailed rules that are intended to provide a rule for as many situations as possible, while abstract games gloss over points in the interest of quick and engaging game flow. Due to cost/complexity, the most popular current wargames tend to be in the middle of the skirmish/campaign axis and are rules-“lite” (abstract).

For learning about military operations, I find two specific blends of the axes to be efficient. Skirmish games (Infinity, Bolt Action, etc.) in the middle of the simulationist/abstract axis are exceptional at addressing small scale unit tactics, forcing hundreds of small decisions over the course of a game, and are generally decided by whichever player has a better tactical plan to address the unique mission parameters for the game in question. Because each player has a relatively small toolbox and is punished extensively for lapses (losing one piece of less than a dozen is a significant detriment), decisions tend to be more carefully considered, and games often come down to capitalizing on unique capabilities. Because these games also tend to be quick to play, it is also beneficial because it allows players to learn quickly from mistakes and execute three or four games in the space of one larger game.

On the other hand, simulationist/campaign scale games (large games played over time, where tactical battles are pulled from a reserve of forces already committed to a larger game board) are excellent opportunities for players (or,  more frequently, teams of players) to put together war plans that are dependent on strategic elements (economic production capacity, reinforcement timelines, popular sentiment, etc.), as well as incorporating ‘state-adjacent’ actions like negotiations, cease-fires, and armistices. Battletech is the most long-running and best established conventional Strategic Operation ruleset, but several others exist in varying forms.

more frequently, teams of players) to put together war plans that are dependent on strategic elements (economic production capacity, reinforcement timelines, popular sentiment, etc.), as well as incorporating ‘state-adjacent’ actions like negotiations, cease-fires, and armistices. Battletech is the most long-running and best established conventional Strategic Operation ruleset, but several others exist in varying forms.

If you could imagine the perfect wargame, what would it look like?

Having some experience with Warfighters’ Simulation or WarSim (not as much as I’d like, but a few Warfighter exercises), my opinion is that WarSim is currently a 50% solution. The main failure of WarSim, in my opinion, is leaning FAR too heavily on being a simulator of real asset/platform capabilities, and far too little on being able to represent external factors and complexities. WarSim and Warfighter exercises concentrate on the Division and Corps levels, and an expansion of simulation facilities for smaller scale operational and tactical engagements, with real-time feedback to higher echelons, would be the most accurate wargame that could be produced. For example: skirmish-scale simulations tailored for platoons and companies alongside operational-scale simulations for battalions and brigades. Real logistical and economic simulation models for flow of war material and personnel reinforcement (especially if those assets can be interdicted or otherwise disrupted) would add complexities that will be realistic for a modern war.

In addition, wargames should include state actors as much as possible, with political impositions and complexities related to the theater of war – more than simply drawing a red box and claiming an area to be a ‘cultural site’. The other aspect that is not well represented in WarSim is the physical environment of complex urban terrain, specifically three-dimensional environments. Urban modelling technology exists and is being routinely utilized in modern video games (especially procedural terrain generation). Large scale procedural terrain generation technology can provide a nearly limitless variety of contested space to test LSCO concepts. Several other grand-strategy games currently on the market represent political, economic, and information elements of national power far more capably than WarSim, even when specifically addressing Divisional and Corps level wargames. Overall, modern game developers have an extensive array of industry knowledge that is underutilized by current defense wargames.

A ‘perfect’ war game, in my opinion, is a different system depending on who I am training. A platoon leader or company commander needs the ability to try and fail in a diverse series of tactical problems across dramatically varying terrain sets. A battalion or brigade commander and staff need a realistic operational environment that includes not only tactical operations, but theater-specific socio-political complexity, realistic economic considerations at echelon (local procurement, material/personnel flow), and distributed operations across time/space with actual time lag and/or imperfect information. Lastly, Division and Corps-level simulations need to have a dramatically expanded Area of Interest for their war games, to include the nation(s) political environment, theater support asset representation (Joint capabilities, theater sustainment, etc.), and actual attrition modelling (fighting with depleted assets/personnel). Most units in the real world of modern conflicts are routinely engaging and reorganizing around a core of 60-80% strength units, and I don’t believe our current wargames adequately model the tactical reality of degraded units.

A ‘perfect’ war game, in my opinion, is a different system depending on who I am training. A platoon leader or company commander needs the ability to try and fail in a diverse series of tactical problems across dramatically varying terrain sets. A battalion or brigade commander and staff need a realistic operational environment that includes not only tactical operations, but theater-specific socio-political complexity, realistic economic considerations at echelon (local procurement, material/personnel flow), and distributed operations across time/space with actual time lag and/or imperfect information. Lastly, Division and Corps-level simulations need to have a dramatically expanded Area of Interest for their war games, to include the nation(s) political environment, theater support asset representation (Joint capabilities, theater sustainment, etc.), and actual attrition modelling (fighting with depleted assets/personnel). Most units in the real world of modern conflicts are routinely engaging and reorganizing around a core of 60-80% strength units, and I don’t believe our current wargames adequately model the tactical reality of degraded units.

What Great Power peripheral flashpoints are you gaming?

The most popular flashpoints in WarGame: Red Dragon are the South China Sea/East China Sea/Taiwan strait, the Baltic region/Finnish border, and a joint forcible entry of Iraq. Team Yankee is a tabletop wargame that focuses on a renewed push in Poland/eastern Europe. Lastly, several simulation wargames have popular flashpoint scenarios concerning a renewed Korean conflict or a future China/India conflict over the Line of Actual Control. Depending on the wargame in question, several also focus on alternate history scenarios, but those tend to be less applicable to real-world Army wargame application.

The most popular flashpoints in WarGame: Red Dragon are the South China Sea/East China Sea/Taiwan strait, the Baltic region/Finnish border, and a joint forcible entry of Iraq. Team Yankee is a tabletop wargame that focuses on a renewed push in Poland/eastern Europe. Lastly, several simulation wargames have popular flashpoint scenarios concerning a renewed Korean conflict or a future China/India conflict over the Line of Actual Control. Depending on the wargame in question, several also focus on alternate history scenarios, but those tend to be less applicable to real-world Army wargame application.

What emergent technologies are you integrating?

In an ironic twist of the current movements towards autonomous systems, the most effective technologies in most wargames I have been playing have focused on cheap and scalable technologies, specifically any munition system that can produced cheaply and at large scale. The promulgation of commercial drone warfare has been routinely discussed for more than a decade now, and the use of small remote-control versions for reconnaissance, ground/naval strike, and disruption is proving to be just as effective as it was predicted to be in wargames. Some things that have seen a huge degree of success in games based on cost/utility include:

-

-

-

UAF FPV Drone with the 53rd (Volodymyr Monomakh) Separate Mechanized Brigade / Source: Facebook page for the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, via Ukrainska Pravda Unmanned air-attack, air-support, and air transport platforms replacing manned flight: Removing the pilot, from an engineering perspective, means a dramatic reduction in weight and the ability to push the turning radius and capability of the platform itself. This also removes the need for crew rest cycles, making maintenance the sole remaining operational downtime requirement. Operators and human skill can be retained through ground control stations, with limited autonomous features in place to return drones to home station in case of signal loss. Air defense technologies are improving dramatically, so cheaper platforms that minimize or eliminate risk to experienced pilots are essential. Bottom line: the advantages of removing pilots from airframes are myriad, and most of the technologies required to do so already exist. [Check out Unmanned Capabilities in Today’s Battlespace]

-

-

-

-

-

Admiral VTOL UAV, a Russian First Person View (FPV) drone-carrying mothership with two drones slung underneath. / Source: Russian MoD via X (Twitter) and Forbes Small-scale semi-autonomous drone carriers: Mobile launch-platforms that are not reliant on existing airfields or naval carrier groups. This ties into the concept of drones in the combat space, but cheap carriers capable of tactical power generation, munition re-stock, and mobility during re-charge cycles have had dramatic impacts against traditional mobile firepower (IFV’s, armor). Cheap drone carriers can launch their payload, re-locate, and pick up drones from an alternate location. All of the technologies to create these platforms already exist, and they are commonly used by commercial events (e.g., drone light shows). Military retrofit is a feasible next step. As more compact long-range drones are developed, these provide an alternate launch point for mid-range air-to-air strike capability or loitering air supremacy projection. [Check out The Swarm Mother]

-

-

-

-

- Smaller-scale naval launch platforms, temporary floating facilities: Naval vessels with a single-squadron launch capability, with massively reduced requirements for depot maintenance and munition storage and much more robust point and mid-range defense capabilities. These vessels are far cheaper in personnel and asset requirements and allow for a much more significant ‘coverage map’ comparative to traditional carrier strike groups. Depot level maintenance and re-arm is conducted at shore facilities/friendly partner/ally nations. Cheaper cost of the vessel to maintain, smaller crew complement, and reduced scale of catastrophic loss in the case of vessel destruction makes placing them far more aggressively in contested space feasible.

-

-

-

-

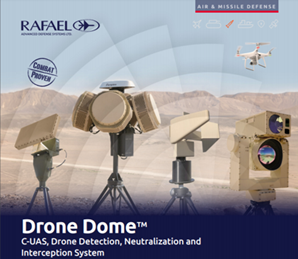

Drone Dome, an Israeli Counter-Unmanned Aerial System (C-UAS) by Rafael / Source: TRADOC G-2‘s OE Data Integration Network (ODIN) Worldwide Equipment Guide (WEG) Short range, cheap, re-loadable Anti-air capability: Anything that can effectively engage drones within 300m is most desirable (e.g., short burst lasers, directed electro-magnetic pulse, low-velocity flak). Most important is that the system is inexpensive and widely deployable. In general, whichever force is less saturated with these systems pays a heavy price through small scale strikes. [Check out Revolutionizing 21st Century Warfighting: UAVs and C-UAS]

-

-

-

-

- Electronic Countermeasures: All of the ‘near future’ wargames have a three-fold arms race between electronic countermeasures, electronic counter-countermeasures, and electronic counter counter-countermeasures (ECM, ECCM, E3CM). Airwave communication is often unreliable at best. High energy tight-burst communications traffic and wired communications make a comeback in a lot of simulations where one side or the other heavily invests in ECM technologies.

-

-

-

- Cheap Short/Medium/Long-range Anti-air missile systems: Stealth technology is more expensive than detection technologies. Proximity is the enemy of stealth systems. Saturating airspace with cheap passive detection drones and having the ability to saturate airspace from missile bases is often more effective at pulling fighters out of the sky than running dedicated airspace interdiction missions. Patriot and near-future equivalents do horrific damage to air assets if they can be employed and protected from enemy targeting.

-

-

-

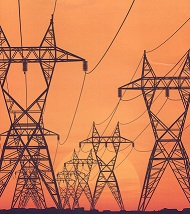

Attack the utilities: Power generation is key — future technologies attacking power generation and identifying power generator running signatures is often how you identify command posts in many games. Water is heavy to transport and essential for both personnel and equipment – control of water production facilities (specifically filtration) and forcing the enemy to transport water for sustainment from out of theater is devastating on their ability to continue offensive action (especially if you can simultaneously target air and naval convoy routes in contested space). [Check out In the Crosshairs: U.S. Homeland Infrastructure Threats]

Attack the utilities: Power generation is key — future technologies attacking power generation and identifying power generator running signatures is often how you identify command posts in many games. Water is heavy to transport and essential for both personnel and equipment – control of water production facilities (specifically filtration) and forcing the enemy to transport water for sustainment from out of theater is devastating on their ability to continue offensive action (especially if you can simultaneously target air and naval convoy routes in contested space). [Check out In the Crosshairs: U.S. Homeland Infrastructure Threats]

-

-

-

- Lingering Munitions: Munitions that strike a target, produce a disabling effect, and then produce a lingering ‘threat’ that prevents recovery or a secondary attack against maintenance or recovery crews. Anything that can produce a mobility-kill effect on a target, and then provide a secondary effect that can disable or defeat recovery crews or indicate that a recovery effort is in progress. Being able to target conventional military vehicle recovery platforms dramatically reduces the ability for depot maintenance to restore assets to the fight and reduces the enemy ability to recycle experienced crews into the fight.

-

-

-

Tactical guided missile system promulgation: The common ‘evolution’ of infantry systems is towards more complex and sophisticated targeting lasers and technologies, specifically geosynchronous satellite support to ground laser technologies. Taking Javelin launchers and heavy munitions off ground Soldiers makes them more mobile and extends their range. In turn, forward infantry elements are paired with mobile ‘dumb’ tactical launcher platforms in the rear-area that can deliver a strike-on-the-move capability to forward infantry elements, the munition itself being a cheap IR-seeker equipped warhead on a simple carrier (in many games, typically a PLS configured load system). There are many, many others, but modern wargames give a lot of space to player-driven customization [i.e., tactical innovation and rapid adaptation] within the rule sets, and being able to generate capabilities from current technologies is something many point-based game systems allow players to do. [Check out The Operational Environment’s Increased Lethality]

Tactical guided missile system promulgation: The common ‘evolution’ of infantry systems is towards more complex and sophisticated targeting lasers and technologies, specifically geosynchronous satellite support to ground laser technologies. Taking Javelin launchers and heavy munitions off ground Soldiers makes them more mobile and extends their range. In turn, forward infantry elements are paired with mobile ‘dumb’ tactical launcher platforms in the rear-area that can deliver a strike-on-the-move capability to forward infantry elements, the munition itself being a cheap IR-seeker equipped warhead on a simple carrier (in many games, typically a PLS configured load system). There are many, many others, but modern wargames give a lot of space to player-driven customization [i.e., tactical innovation and rapid adaptation] within the rule sets, and being able to generate capabilities from current technologies is something many point-based game systems allow players to do. [Check out The Operational Environment’s Increased Lethality]

-

What compelling insights from gaming would you like to share with the US Army?

The simplest things I’ve learned from wargames in my free time is that the person that can get their assets to the fight, and then resupply those assets over time as they suffer attrition, is the side that typically wins. Complex technologies tend to dominate the battlefield and are utterly decisive for the first few games, but typically the resource cost (points, C-bills, abstract currency equivalent) are unsustainable. The most important thing that tends to result in the overall victor is whoever can continue to produce ‘good-enough’ systems. Cheap, durable, and deployable at scale are the most dominant factors for effectiveness in campaign scale wargames.

The simplest things I’ve learned from wargames in my free time is that the person that can get their assets to the fight, and then resupply those assets over time as they suffer attrition, is the side that typically wins. Complex technologies tend to dominate the battlefield and are utterly decisive for the first few games, but typically the resource cost (points, C-bills, abstract currency equivalent) are unsustainable. The most important thing that tends to result in the overall victor is whoever can continue to produce ‘good-enough’ systems. Cheap, durable, and deployable at scale are the most dominant factors for effectiveness in campaign scale wargames.

Tactical drone operations and tactical drone defense are critical capabilities and need to be a basic concept for near-future warfare – the current model of treating drone flights as air missions (with all associated mission planning, paperwork, and complex asset recovery process) is foolish. Cheap drones exist and are not going away — all tactical Soldiers need to be incredibly  comfortable and knowledgeable with drone reconnaissance and drone strike capability immediately. Not 3 years from now in the next doctrine review cycle.

comfortable and knowledgeable with drone reconnaissance and drone strike capability immediately. Not 3 years from now in the next doctrine review cycle.

Line infantry die in droves without sophisticated support capabilities, specifically terrain shaping and real-time reconnaissance. Most infantry in LSCO game scenarios exhaust their effective anti-tank munitions before being able to defeat (most) armored formations.

Miniaturized and/or portable terrain shaping technologies (shaped demolitions, modular emplacements, small-scale counter mobility solutions) are massively effective in dense terrain – specifically urban and subterranean. In most games, mobility solutions always lag behind counter-mobility problems.

We hope this post has piqued your interest regarding how wargaming can inform us about the Operational Environment and support Professional Military Education. Army Mad Scientist and the Georgetown University Wargaming Society want to invite you to learn more about this topic at our Game On! Wargaming & The Operational Environment Conference.

What: An in-person conference to explore Wargaming and how it can help the Army better understand the Operational Environment

When: 6-7 November 2024

Where: The Healey Family Student Center, Georgetown University, 3700 Tondorf Road, Washington, DC 20057

Why: To explore new wargaming methods, new ways to incorporate learning into Professional Military Education, and have an open dialogue with wargamers inside and outside the military.

***In order to attend, you must register through Eventbrite — click here now to reserve your seat — access will be limited to registered attendees only!***

Stay tuned to the Mad Scientist Laboratory for conference updates and forward any questions you may have to madscitradoc@gmail.com

In the meantime, check out the following Mad Scientist Laboratory wargaming related content:

Taking the Golf Out of Gaming and associated podcast, with Sebastian Bae

“Best of” Calling All Wargamers Insights (Part 1)

Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response (CHMR) Considerations in Wargaming LSCO, Achieving Victory & Ensuring Civilian Safety in Conflict Zones, and associated podcast with Andrew Olson

Brian Train on Wargaming Irregular and Urban Combat

Live from D.C., it’s Fight Night (Parts One and Two) and associated podcasts (Parts One and Two)

Would You Like to Play a Game? Wargaming as a Learning Experience and Key Assumptions Check and “No Option is Excluded” — Using Wargaming to Envision a Chinese Assault on Taiwan, by Ian Sullivan

Using Wargames to Reconceptualize Military Power, by proclaimed Mad Scientist Caroline Duckworth

Gaming the System: How Wargames Shape our Future and associated podcast, with guest panelists Ian Sullivan, Mitchell Land, LTC Peter Soendergaard, Jennifer McArdle, Becca Wasser, Dr. Stacie Pettyjohn, Sebastian Bae, Dan Mahoney, and Jeff Hodges

The Storm After the Flood virtual wargame scenario, video, notes, and Lessons Learned presentation and video, presented by proclaimed Mad Scientists Dr. Gary Ackerman and Doug Clifford, The Center for Advanced Red Teaming, University at Albany, SUNY

Gamers Building the Future Force and associated podcast

About the Author: CPT Spencer D. H. Bates is a Combat Engineer and Team Leader with Engineer Advisor Team 5521, Bravo Company, 5th Battalion, 5th Security Force Assistance Brigade (SFAB), Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington. He has been an avid wargamer since his early teens, which he ultimately attributes to his pursuing a career in military service. He is also an avid player, reviewer, and organizer of large-scale wargame events.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).