[Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist Laboratory is pleased to publish today’s post by returning guest blogger Mr. Ian Sullivan, addressing the paramount disruptor — people and ideas. While emergent technologies facilitate the possibility of change, the catalyst, or change agent, remains the human with the revolutionary idea or concept that employs these new tools in an innovative way to bring about change in the character of future warfare.]

There is a passage in Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front that has always colored my views on the future. In it, Alfred Kropp, the thoughtful school pal of main character Paul Bäumer, is having a discussion with his friend about a war that has metastasized from a youthful, joyous adventure into a numbingly horrific slog.

“But what I would like to know,” says Albert, “is whether there would not have been a war if the Kaiser had said No.”

“I’m sure there would,” I [Paul] interject, “he was against it from the first.”

“Well if not him alone, then perhaps if twenty or thirty people in the world had said No.”

“That’s probable,” I agree, “but they damned well said Yes.”

Ruminating on the First World War, a conflict that most leaders of the day thought would be over in a few weeks, but one that futurists should have realized would become something else altogether, Alfred and Paul hit upon a salient point. European armies met for a battle they could not imagine. Generals versed in Napoleon suddenly faced a true industrial age war. Sure, there were signs hinting at what could come. The post-Gettysburg U.S. Civil War, for example, offered a glimpse of this type of fight, as did the Franco-Prussian War, and even the Second Anglo-Boer War.

In a total war, pitting society against society, where the battlefield was dominated by rapid-firing artillery, machine guns, and chemical warfare; where whole societies were pitted against each other to match the industrial requirements of the war, to sustain and reconstitute fighting forces; and where the civilian populations were directly targeted by naval blockades, aerial bombardment,

and other deprivations, it is easy to see the critical role that technology played. However, Alfred and Paul remind us that no matter how much technology advances, or how it shapes the world, the most significant, relevant, and system-altering changes come not from technology, but from people and the ideas and beliefs that shape their behaviors and enable decisions.

The world of today, looking forward, is at least reminiscent of the pre-Great War period. Technology is advancing rapidly; indeed, it is advancing so fast that changes in the way we live, create, think, and prosper are occurring at a dizzying pace. New and converged technologies have led us to question what shape society will take, and dramatic changes which were once only the province of science fiction seemingly become science fact at a swift clip. Information technology, artificial intelligence, quantum computing, robotics, additive manufacturing, and other technological advances have increased or soon will further expand the speed of human interaction.  These technologies already have changed society, and will continue to do so as they mature, spawn convergences, and lead to the creation of a new series of technological wonders. TRADOC’s “Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Future Warfare” asserts the future is governed by two drivers; the rapid societal change spurred by these technological advances and the changes these advances will have on the character of warfare. But this assessment may be incomplete, or perhaps it is too deterministic in nature, because at the end of the day, there is a third driver, and it deals with people and ideas.

These technologies already have changed society, and will continue to do so as they mature, spawn convergences, and lead to the creation of a new series of technological wonders. TRADOC’s “Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Future Warfare” asserts the future is governed by two drivers; the rapid societal change spurred by these technological advances and the changes these advances will have on the character of warfare. But this assessment may be incomplete, or perhaps it is too deterministic in nature, because at the end of the day, there is a third driver, and it deals with people and ideas.

The latter part of the Nineteenth and early part of the Twentieth Centuries also were dominated by advances in technology. We saw industrialization on a massive scale, the development of internal combustion engines, aviation, telephony, the widespread use of railroads, and other remarkable changes. Alfred and Paul must have thought that the pace of human interaction was increasing exponentially. Yet, while these technologies clearly had societal impacts, they were not transformational on their own. Indeed, they served only to reinforce the power structures that stemmed from the end of the Enlightenment and the reaction to the French Revolution and Napoleon. For as much as society changed, for as much as sub-groups were empowered, as much as “super-empowered individuals” like Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Henry Ford, or the Krupp family garnered influence and even some power, it was a handful of individuals – Alfred postulated 20 or 30 – who made the decision to go to war in 1914.

And in spite of the technological advances of the era, it was the thought processes and ideals generated – a time when Marxism, nationalism, imperialism, social Darwinism, and existentialism, among other schools of thought were developed and refined – that influenced these 20 or 30 individuals who held in their hands the fate of the world in August 1914, and the multitudes of others who would see the war that transpired to the end.

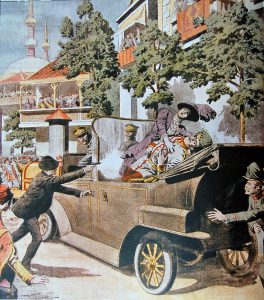

So again, why is this important to the futurist? Because we see technological marvels and focus on their impact, noting that they will drive change that will compel society to follow. Technology is exciting, and its prospects are wondrous. It can and will drive change. But it does not drive change alone; ideas and people still play a role. The spark that caused the First World War,

Gavrilo Princip’s assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was lit by one man but driven by Princip’s exposure to nationalism. The Russian Revolution, triggered as a popular reaction against the war and the ruling Romanov dynasty certainly was guided by ideology across many spectrums. Idealism also went hand-in-hand with the American perception of World War I, as a nation geared up in a spasm of Wilsonian idealism to “make the world safe for democracy” and to fight “a war to end all wars.” In the end it was the convergence of ideas, human decision-making, and technology that drove change, in this case, the onset of World War I.

A casual glance at newspaper, or more likely, scanning news notifications on your smart phone, shows us a world that is in large part driven by thought, ideal, and belief. In spite of technology, the speed of human interaction, and global connectivity, we see a retrenchment of globalization and an assertion of nationalism and regionalism around the globe. Whether it be China’s expansionist “One-Belt, One-Road Initiative,” Russia’s adventurism in the Near Abroad and Syria, Brexit in the UK, or a renewed focus on “America-First” from Washington, a renewed sense of nationalism is evident worldwide. Additionally, autocratic regimes are experiencing something of a resurgence; Kim Jong Un in North Korea, Vladimir Putin in Russia, and even a Saudi Royal Family that is now under suspicion of murdering a journalist. We’ve also seen China putting up walls on Internet accessibility and a focus by state actors on crafting narratives aimed at influencing subsections of populations and fostering dissent within rival nations. Individuals too, like Princip before them, also can play a role.

The Arab Spring, for example, was sparked by one man in Tunisia with a grievance, but soon went viral on Social Media and led to a significant change in the Middle East. In these cases, technology may serve not as a driver, but instead as an enabler of the human driver.

As a futurist, I am concerned when so much of our effort focuses on one aspect of change, in this case, technology. I have attended many events focusing on the future, read a number of authors who focus on the radical changes AI or quantum computing will have on society, and seen many very similar interpretations of the way the future will unfold. Indeed, views of the future are coalescing around technological innovation compelling broader societal changes. It is clear that technology is a driver that needs to be studied.

But it is equally important to understand what drives thought and belief, and how these can be shaped and influenced, for both good and nefarious purposes. My intention in starting with Remarque was not to force a dystopian or deterministic view of the future. Nor am I falling back on George Santayana’s observation about a failure to learn history. History is important, as it shows us how events unfolded, and allows us to understand how problems developed; however, I do not believe we are doomed to repeat August 1914.  But I do believe that we need to spend as much time looking at the intellectual, emotional, and even popular Zeitgeist to understand how people view the world and make decisions in light of all of the changes that technology is bringing around us. We need to learn not only what is happening, but must ask ourselves the hard “why?” and “so what?” questions, lest we be unable to understand and warn our leaders during some crisis in August 2028.

But I do believe that we need to spend as much time looking at the intellectual, emotional, and even popular Zeitgeist to understand how people view the world and make decisions in light of all of the changes that technology is bringing around us. We need to learn not only what is happening, but must ask ourselves the hard “why?” and “so what?” questions, lest we be unable to understand and warn our leaders during some crisis in August 2028.

If you enjoyed reading this post, please also see:

Lessons Learned in Assessing the Operational Environment, by Ian Sullivan.

Character vs. Nature of Warfare: What We Can Learn (Again) from Clausewitz, by LTC Rob Taber.

Ian Sullivan is the Assistant G-2, ISR and Futures, at Headquarters, TRADOC.

Cultural, technical, economic and social change impacts the future of conflict. Future conflict has an increasingly perilous disruption that is hinted at in the changing views espoused concerning the onset of WWI and factors affecting global conflict.

When multidomain conflicts assert aggression in all domains the prospect of a sanctuary becomes vanishingly small. Past conflicts witnessed spectacular advances in aggressor capabilities with fewer no-less remarkable defense systems. Antimissile and antiaircraft systems evolved after WWII to counter offsets in military strategies. In conceiving future conflict whether conventional, gray-zone or asymmetric it would seem useful to question the nature of warfare in the absolute absence of sanctuary.

Attacks on communications and electronic systems have the prospect of paralyzing a market economy, suspending transportation and trade and arresting population mobility without regard to the form of government or location of targets. Kinetic attacks may evolve to include bio and chemical agents that transform in the wild resulting in unpredictable consequence. Most importantly, in the absence of sanctuary, every citizen without regard to color, gender, creed or cultural norm is a combatant either willing or unwilling. There is no safe zone. From one perspective, this is the future of warfare independent of technology advances. The notion of civil defense faded from popular culture as the stress of the cold war wound down. Will the future of civil defense in a contest of global power resemble a video game with life and death consequence or more similarly resemble the under-desk duck and cover approach as a palliative for the public? Will future conflict engage man-machine teams without regard to the consequence for noncombatants? Will the apparent need to suppress logistics support on a global scale reduce future contests to political disputes that erupt in a series of global all-out salvos of weapons and force projection? Technology has made the world a smaller place. The reliability of news reporting and fact-based decisions have been gradually overwhelmed by instant messaging at a pace that leaves no room for quality journalism and trusted verification. Fact has been replaced by 80% solutions based on a gathering of intelligence fragments and sensor reports. Perhaps a new age of discovery, a process of conflict resolution beyond expression of military force and attention to the basic cultural and social needs will mitigate unconstrained military engagements. In a power-balancing act, the solution is harder to predict and may be a matter of crossing a defining rubicon just as two global conflicts before. Military offset, the tenuous balance of force and power and the opportunity for self-sufficiency, growth and expansion would seem to be the best military posture.

In complete agreement, the human aspect of conflict drives decisions, and parallels between current time and points in the past has merit. But there is danger in using history as a significant factor in predictive analysis of future events given the speed of transformative technology, which daily is being given increasing capability to drive decisions, particularly with the advent of AI.

The most striking example from the article, in my opinion, only received a passing mention; the use of transformational technologies to reinforce existing power structures. We live in interesting times, and traditional power structures (Post-WW II) and international relationships continue to break down. Some examples being the expanding, extra-regional influence of China, the emerging thought of a non-NATO European state and the rise of non-state actors in physical and cyber domains, all of these show that human ideas empowered by technology will drive future conflict, in concert, not necessarily in isolation from each other.

Yet as new capabilities come into production, systems purpose- designed to counter a single threat capability such as missile defense systems that have nano-seconds to make decisions. Systems enabled by AI will demand human vigilance to evolve alongside our technology lest we become irrelevant, and the 20 or 30 become a smaller circle of network brains saying yes instead of our leaders.