[Editor’s Note: This past spring, Army Mad Scientist sought to crowdsource the intellect of the Nation (i.e., you — our community of action!) with our Calling all Wargamers flyer, soliciting input about your wargaming experiences:

-

-

- What are you learning about Large-Scale Combat Operations (LSCO)?

-

-

-

What wargames do you find useful for learning about military operations?

What wargames do you find useful for learning about military operations?

-

-

-

- If you could imagine the perfect wargame, what would it look like?

-

-

-

- What Great Power peripheral flashpoints are you gaming?

-

-

-

- What emergent technologies (or convergences) are you integrating into your wargaming?

-

-

-

- What compelling insights from gaming would you most like to share with the U.S. Army?

-

We were overwhelmed with the number of responses we received (both domestic and international!) and are featuring more of your compelling insights in the run up to our Game On! Wargaming & The Operational Environment Conference, co-hosted with the Georgetown University Wargaming Society, on 6-7 November 2024 — additional information on this event and the links to our registration site and conference agenda may be found at the end of this post.

Today’s post captures our second and final tranche of the “Best of” insights you submitted — Read on!]

What are you learning about large scale combat operations?

1. I am learning that Large-Scale Combat Operations (LSCO), including the use of long-range fires, autonomous systems, drones, and logistics is a very complex task. And, regardless of what industry is claiming, there isn’t a computerized wargame that can make game play (especially for decision) any easier. – Jeff Hodges, Training Integration Manager, U.S. Army Modeling and Simulation School

2. That Multi-Field Multi-Domain (M2MC [France’s analog to Multi-Domain Operations]) is both complex AND simple and that the fundamentals of war are still there. If everybody’s accelerating, the frontal shock might be great, but the relative speed remains constant. When Intelligence, Surveillance,  Reconnaissance (ISR) and Electronic Warfare (EW) replace Mark I eyeballs for everybody, is it really a game changer? But what strikes me the most is the importance of modelling logistics, which are much more relevant than tactical conundrums. — Antoine Bourguilleau, Historian, Game Designer, and Major in the French Army, in charge of developing jeu de guerre [wargame] capabilities (also the author of Jouer la guerre – Histoire du wargame — first book in French on the subject) and in PhD program on “modelling war.”

Reconnaissance (ISR) and Electronic Warfare (EW) replace Mark I eyeballs for everybody, is it really a game changer? But what strikes me the most is the importance of modelling logistics, which are much more relevant than tactical conundrums. — Antoine Bourguilleau, Historian, Game Designer, and Major in the French Army, in charge of developing jeu de guerre [wargame] capabilities (also the author of Jouer la guerre – Histoire du wargame — first book in French on the subject) and in PhD program on “modelling war.”

3. I am learning about the difficulties of coordination of effort, even while gaming modern/hypothetical battles. It is very clear in conflicts from earlier eras (e.g., Blind Swords and ACW), but it comes through in modern games also. Typically, it is manifested as balancing the allocation of resources based on the goals of conflict. In large scale battles, there is a need to prioritize efforts and to determine how to “hold the line” in other areas. — Donald Levick

4. O n the tabletop, like the field, the synchronization and sequencing of combat multipliers matters. Enablers allow one to achieve an asymmetrical advantage. Figuring out how to use and exploit your enablers such as fire support, intelligence, engineers, and minimize the opponent’s enablers, creates non-linear and cascading effects. Generally, in most games this is hard to do effectively, as there is a series of trade-offs, risk, if you will. And a non-cooperative adversary does not help.

n the tabletop, like the field, the synchronization and sequencing of combat multipliers matters. Enablers allow one to achieve an asymmetrical advantage. Figuring out how to use and exploit your enablers such as fire support, intelligence, engineers, and minimize the opponent’s enablers, creates non-linear and cascading effects. Generally, in most games this is hard to do effectively, as there is a series of trade-offs, risk, if you will. And a non-cooperative adversary does not help.

Ultimately, it is about interdependent decision-making. In other words, my best course of action is not necessarily the optimum one, but the most effective based upon what the opponent(s) does. This is probably my biggest weakness in any game environment, because its hard and adds a heavy layer of thinking to the problem—The Princess Bride conundrum (“I know that you know, that I know, that you know…”). The ideal process is to determine my objectives, then anticipate the enemy’s actions, and adjust my approach to achieve to best POSSIBLE outcome (maximax in decision/game theory). Wargames allow us to explore this loop in a safe environment. Reflecting on your own decision-making encourages personal growth and builds experience.

Another interesting insight is the principles of war (objective, offensive, mass, economy of force, maneuver, unity of command [effort], security, surprise, and simplicity) are very useful in describing the actions, decisions, and risk, while evaluating the outcomes. In short, games provide an immersive experience to feel the difficulty in managing a dynamic battlefield and scarce resources—and learn. – Steven Sallot, Wargame Designer, Strategic Wargaming Division, U.S. Army Center for Army Analysis (CAA)

Another interesting insight is the principles of war (objective, offensive, mass, economy of force, maneuver, unity of command [effort], security, surprise, and simplicity) are very useful in describing the actions, decisions, and risk, while evaluating the outcomes. In short, games provide an immersive experience to feel the difficulty in managing a dynamic battlefield and scarce resources—and learn. – Steven Sallot, Wargame Designer, Strategic Wargaming Division, U.S. Army Center for Army Analysis (CAA)

What wargames do you find useful for learning about military operations?

1. I am fascinated by the idea of an operational level wargame that would abstract at an echelon that allows for fairly rapid game play without overburdening the players / facilitators with volumes of rules, rule exceptions, and multiple combat table resolutions per turn. I haven’t found this game yet. — Jeff Hodges

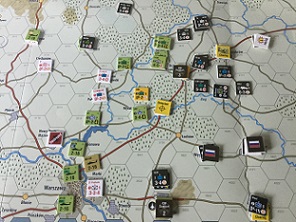

2. GMT’s Next War series is an ok look at modern conflict from a much abstracted view. I prefer zooming in a bit to get more flavor — even looking at one aspect at a time. GMT’s Red Storm and others of the series give a good operational and somewhat tactical look at modern air warfare. — Alan Van Meter

3. Sebastian Bae’s Littoral Commander or Tim Barrick’s OCS series — Dr. Curtis G. Miller, Research Staff Member, Institute for Defense Analysis (IDA)

4. For modern and hypothetical warfare, I find the GMT Next War system to be the most instructive. It models combined arms very well and addresses complex issues such as range, coordination of units within/between countries, supply, and the use of modern weapons (including drones, cyberwarfare, etc.) — Donald Levick

5. Keep ‘Em Rolling – This board game focuses almost exclusively on logistics and to my knowledge is one of the very few commercial wargames to do so. Players assume the role of Patton, Bradley, or Montgomery in driving across France in 1944. They must establish and maintain supply lines along an increasingly fragile network; plan on pre-positioning supplies at key nodes as contingencies for combat; and develop alternate plans should the other players divert a needed class of supply for their own needs. Even though all players are technically on the Allied side, it is an intensively competitive game where all players draw from a common and limited supply pool.

This War of Mine – Both a computer and tabletop game, I prefer the tabletop version because it allows more players to participate. It is one of the few wargames to focus solely on the civilian experience in war, as well as present difficult ethical dilemmas. It’s loosely based on fighting around Sarajevo in the 1990s, and players take the roles of various civilians displaced by the fighting who are simply trying to survive while caught between two belligerents. Players must secure supplies; harden their shelter against weather, thieves, and roaming soldiers; deal with medical and morale problems; and face ethical problems such as whether they should steal food from other displaced civilians to prevent one of their party from starving. I’ve often been frustrated that many wargames simply remove civilians from the battlefield, or only consider the challenges of fighting in urban areas to be impediments to movement or providing defensive bonuses. This War of Mine is entirely about the civilian perspective, something I think is of vital consideration to military decision-makers at any level.

Micro-wargames – this is a relatively new genre for me, but I have fully embraced it as an additional avenue for introducing new players to wargaming. Micro-games are small both in physical footprint and complexity – they are designed to fit onto a single sheet of paper, require few to no additional pieces (maybe a dice or two), and are laser-focused on one specific theme. These games can be played in 30 minutes or less, which is great for military players who may not have much additional bandwidth. They are also normally available for free from the designers, making them a low-cost/high-return wargaming option. An example of these games is a collection focused on the INDOPACOM region, to which I contributed one game focused on delivering supply by air in INDOPACOM’s unpredictable weather patterns — see: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1hWtrQs7HSL-rV5btlTTX6aIl4m2Ern8Q?usp=drive_link — Ian Brown (Retired from the Marine Corps last year; spent last four years in uniform as the operations officer for the Brute Krulak Center for Innovation and Future Warfare, where supporting Marine Corps University schools with wargaming was one of his primary tasks).

6. Section-by-Section–Vietnam—Medic! This is both a section to company-level wargame in eight scenarios based on historical battles from 1963 to 1970, with a full range of ground and air weapons, whilst simultaneously taking on the role of medics in the Vietnam War. When fighting the battles, you also have to treat your wounded under fire and evacuate the casualties, applying triage methods to dictate the order of treatment and evacuation. Casualties rated T1 to T4 with the position of wounds are allocated by spreadsheet in the pattern reported in medical literature of the period.

Central Front SPI – 1956 British Army wargame blended rules: This blend of rules lifts the original game system for a Soviet invasion of Central Europe with the 1956 British Army system to make a manoeuvre and attritional 4-hour based game that plays as a staff officer exercise. Orders are issued for units at regiment or equivalent-level the turn ahead (five types from move to fight to hold combined with three levels of status [march/hasty/ prepared]). The combat system includes EW, chemical, and tactical nuclear weapons and Intel effects in a simple system. This is currently played on Blue and Red boards using Google Drive with an umpire in between on the Purple see-all board. – Ian Robinson and Mark Flanagan, Greylag a.anser4u Ltd game designers.

If you could imagine the perfect wargame, what would it look like?

1. The perfect wargame would be a Division / Corps-level tabletop that would focus on EW, autonomous systems, and contested logistics outcomes. These outcomes would feed a simulation-driven exercise, and be targeted toward the G3 planners, not current operations. I am fascinated by the idea of an operational-level wargame that would abstract at an echelon that allows for fairly rapid game play without overburdening the players / facilitators with volumes of rules, rule exceptions, and multiple combat table resolutions per turn. I haven’t found this game yet. — Jeff Hodges

2. I do not believe that the perfect wargame exists because a wargame that tries to do everything is a bad wargame. However, the wargame that I want to see at the unclassified level is a wargame about a great power conflict where 2-4 players first play a game that “sets the stage,” where they obtain assets and manage diplomacy, then a “conflict” game where they take that start state and use it as the setting for a conflict.– Dr. Curtis G. Miller

3. There is no such thing, unfortunately. The “perfect wargame” is relative: it’s the good game, at the good scale, for the right players, with a challenging level of complexities. If your audience doesn’t know a damn thing about the theater or the operation of the tactical implications of the level played, you are heading for disaster. — Antoine Bourguilleau

4. The ultimate simulation game would be run by a team of planners, gamers, and coders giving two or more opposing teams of players a true sense of the fog of war, and of dealing with a multitude of variables. Planning and timing of execution could be kept track of down to the operational minute. — Alan Van Meter

5. Perfection in wargame design is subjective and hinges on fitness for purpose. An ideal operational-level wargame would be accessible to practitioners of all levels, offering a comprehensive simulation of multi-domain operations without excessive complexity. Striking the right balance between realism and accessibility is crucial, with a transparent game design that is traceable to doctrinal planning factors. Something in between the scale and complexity of Littoral Commander and the Operational Wargaming System would be ideal for this purpose. — Keith Kacmar, an FA59 Strategist deeply immersed in both professional and hobbyist wargaming

6. The perfect wargame would look a lot like Next War (with Advanced and Optional rules); but would streamline the edge cases and standardize some of the outlying rules. — Donald Levick

7. It would probably be a significantly simplified version of Command: Modern Operations published by Slitherine Games. A computer game, it just needs greater abstraction and a more intuitive user interface for medium gamers who aren’t going to put in the hours to master the mechanics and interface. A tabletop game I really like is Heroes of Normandie by Devil Pig Games. It’s a WW2 squad/platoon level game that elegantly captures a lot of detail but makes it very easy to understand and apply. Unfortunately, Devil Pig Games is now defunct, though the original designers are trying to resurrect it under a different name. The follow-on games, add-ons, and expansions are amazing, with some of the highest production values and artwork I’ve seen. [More recently, I’ve started trying out games from Vuca Simulations, and am finding them quite good as well. Their WW2 game, Traces of War, is at the right level of command and detail for me.] — Robert Walton, Kinetic Strike Intelligence, LLC

8. I did not find the “perfect” game already made, so I attempted to make it myself. I have been working for about two years on a deck construction game called #Maneuver Warfare which aims to hit simplicity, accessibility, and relevance. It is focused on Marine Corps capabilities and doctrinal nomenclature, with the “red” opponent being a mix of Russian and Chinese capabilities and nomenclature. The deck construction aspect allows players to perform pre-mission planning by making assessments of what capabilities they will need and then deciding what deployment order those capabilities will appear on the battlefield. I also made the maxim that “war is a clash of wills” a very literal aspect of the game — “Will” is the resource for both players that lets them deploy and take action, and which gets drained when they lose units, fail to provide humanitarian relief, or don’t protect their strategic narrative. The first player to lose all their “Will” loses the game. — Ian Brown

9. The game would be double blind with limited and imperfect information—the enemy might have deceived you. There should be an elegant abstraction and integration of intangibles such as morale, leadership, fatigue, information dominance, etc. There should be sufficient, but imperfect, feedback loop for the players. The players should have the opportunity to evaluate and assess their information—players should always question what they sense. Third, the game should include a real-time record of the players’ decisions, motivations, perceptions, and assumptions. In short, what were the players thinking; and why did they do what they did. Finally, the game should repeatable and allow for multiple iterations – again, encouraging experimentation and facilitating learning. – Steven Sallot

10. A wargame that could incorporate the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) as a player aid. The Team is working closely with HQ SACT’s Digital Transformation Branch to explore incorporating AI into wargaming. — LTC(P) Aaron Beam & Richard Goldblatt, NATO Allied Command Transformation (ACT) Experimentation and Wargaming Branch (EWB)

What Great Power peripheral flashpoints are you gaming?

1. Littoral Commander integrates EW, precision strikes on shipping using island-based HIMARs teams, which require accurate reconnaissance and targeting data from drones, submarines, SIGINT, etc. Decisive Action integrates drones to effectively scout and reconnoiter the Russian support zone areas to find and destroy Command and Control (C2) nodes, artillery, and air defense. Decisive Action also relies heavily on EW employment to disrupt drone C2 networks. — Leo Barron, U.S. Army Intelligence Center of Excellence Instructor (runs a daily wargame club at lunch)

2. Being French, the INDO-PAC is important (Indian Ocean being a focus for the Navy and the Army);Transnistria; the Baltic States; and of course the South China Sea and Taiwan, obviously. Is Ukraine peripheral? I’m not sure. It’s very central (and we play it, too) — Antoine Bourguilleau

2. Being French, the INDO-PAC is important (Indian Ocean being a focus for the Navy and the Army);Transnistria; the Baltic States; and of course the South China Sea and Taiwan, obviously. Is Ukraine peripheral? I’m not sure. It’s very central (and we play it, too) — Antoine Bourguilleau

3. Right now, it’s China versus the US and allies in the Indo-Pacific. I’m using Littoral Commander: Indo-Pacific for that. I look forward to its sequel, Littoral Commander: The Baltics, later this year, and will use that to game Russia and NATO potential conflicts. — Robert Walton

4. Brinksmanship and grand strategy, experienced through games such as Triumph & Tragedy, highlight the challenges of great power competition. Specifically, the confluence of escalation, provocation, deterrence, and surprise. Naturally, this leads directly to indications and warning, and how a great power reacts, either for good or ill.

Another insightful experience of great power wargames comes from a narrow pool of games that specifically break out great powers from a homogenous decision body or polity into multiple players with competing interests. Most wargames have players represent a single side or faction — this makes unity of command/effort easy. Generally, this is untrue, even in totalitarian regimes; the Third Reich for instance. In any case, games where the faction is sub-divided with competing tribes with unique objectives makes for a most interesting game. Simulated Staff Ride Mindanao attempts to highlight this friction when it sub-divides the U.S. into two competing factions: the Joint Force and Department of State. Fundamentally, this is a riff off a semi-cooperative game where players need to work together; however, only one can win.

Lastly, great powers continue to compete using an indirect approach, spanning the Operational Environment variables (political, military, economic, societal, information, and infrastructure or PMESII). These create an interesting decision space, generally beyond the expertise, or at least comfort level, of most military practitioners. Games highlight the interdependence of PMESII and ability to project and sustain military power. – Steven Sallot

Lastly, great powers continue to compete using an indirect approach, spanning the Operational Environment variables (political, military, economic, societal, information, and infrastructure or PMESII). These create an interesting decision space, generally beyond the expertise, or at least comfort level, of most military practitioners. Games highlight the interdependence of PMESII and ability to project and sustain military power. – Steven Sallot

What emergent technologies or convergences are you integrating?

1. Integrating emerging technologies such as Space, Cyber, EW, Information Operations (IO), and AI present a significant challenge in all-domain wargaming. Translating capabilities into unclassified game mechanics, often through card-driven systems, enables players to engage with these technologies effectively. — Keith Kacmar

2. Not much for the moment, I’m really into manual wargames because to me, the most important part happens AROUND the table — it’s the interactions between people. Smartphones and computers tend to isolate people. I don’t want that in my games. I do admit, though, that using my phone’s camera is useful to run double blind games: taking pictures of one board and using it to report to the other what he/she sees. It’s an idea I borrowed from my friends at the CGSC. — Antoine Bourguilleau

2. Not much for the moment, I’m really into manual wargames because to me, the most important part happens AROUND the table — it’s the interactions between people. Smartphones and computers tend to isolate people. I don’t want that in my games. I do admit, though, that using my phone’s camera is useful to run double blind games: taking pictures of one board and using it to report to the other what he/she sees. It’s an idea I borrowed from my friends at the CGSC. — Antoine Bourguilleau

3. Emergent tech includes: cyberwarfare (optional rule), drones (which have reduced the need for air superiority to detect the enemy), DF-21’s [Chinese hypersonic missiles], and other “newer” weapons.– Donald Levick

4. [One that] uses ChatGPT to help write articles for the game’s news updates — Dr. Curtis G. Miller

5. I have not tried a tabletop game with integrated app support, but see some doing that, so maybe I’ll give it a shot at some point. It could make game mechanics a lot easier, capturing the tabletop experience and allowing the mechanics to be resolved by an app. The problem to date is players still have to enter the data for calculations, and gathering and sorting that information is actually the harder part of crunchy mechanics, not the math applied at the end. — Robert Walton

6. I’ve used generative AI to create virtually all the graphics for my #Maneuver Warfare card game, specifically WOMBO Dream. Initially, my decision to do this was driven by resourcing constraints; however, as I continued work on the game, I came to appreciate it as a “meta”-layer to the very themes of future warfare I wanted players to experience when playing my game. AI is going to be part of future warfare, in many shapes and forms — with my game, players hold one of the outputs of AI in their hands and interact with AI outputs every time they play a card. If interested, I discussed my use of generative AI at length in a presentation to the Georgetown University Wargaming Society – check it out at: https://youtu.be/5CmyT0N05NU?si=QQWHoXJs0HXfYU4j. — Ian Brown

6. I’ve used generative AI to create virtually all the graphics for my #Maneuver Warfare card game, specifically WOMBO Dream. Initially, my decision to do this was driven by resourcing constraints; however, as I continued work on the game, I came to appreciate it as a “meta”-layer to the very themes of future warfare I wanted players to experience when playing my game. AI is going to be part of future warfare, in many shapes and forms — with my game, players hold one of the outputs of AI in their hands and interact with AI outputs every time they play a card. If interested, I discussed my use of generative AI at length in a presentation to the Georgetown University Wargaming Society – check it out at: https://youtu.be/5CmyT0N05NU?si=QQWHoXJs0HXfYU4j. — Ian Brown

7. Space/Counter-Space, Cyber, Cognitive/Information Warfare, Multi Domain Operations C2, Emerging Disruptive Technologies, and Informationized and Intelligentized Warfare (China). — LTC(P) Aaron Beam & Richard Goldblatt

What compelling insights from gaming would you most like to share with the US Army?

1. My ‘compelling’ insight isn’t very compelling at all. It’s not fancy, new, AI-influenced, or a product of the commercial environment. That said: combine the power of a tabletop wargame and a low overhead simulation driver that will force a decision, live with the impacts of the decision, and reduce the exercise overhead load by >60%. — Jeff Hodges

2.  As a sci-fi writer, my compelling thing to share is fully embrace drones and micro drones. Their battlefield usefulness will only rapidly increase. For example, picture an AI-controlled drone swarm of small, not micro, Automated Piloted Vehicles (APVs) flying in a wide, semi deep layered formation. Over the target, each releases a mist of fine flour-like explosive particles. Last drone fires flares behind it to detonate the hyperbaric explosion — a potentially quite big one. — Alan Van Meter

As a sci-fi writer, my compelling thing to share is fully embrace drones and micro drones. Their battlefield usefulness will only rapidly increase. For example, picture an AI-controlled drone swarm of small, not micro, Automated Piloted Vehicles (APVs) flying in a wide, semi deep layered formation. Over the target, each releases a mist of fine flour-like explosive particles. Last drone fires flares behind it to detonate the hyperbaric explosion — a potentially quite big one. — Alan Van Meter

3. More complicated games (such as NextWar) provide the opportunity to sandbox different approaches. However, the challenge is that the more complex games require many hours of play and it is difficult for most wargamers to devote enough time to “figure it out.” — Donald Levick

4. The most important insight from any wargame must come from within. Participants need a period of reflection to understand what happened and why. The Bottomline: in order to get most of the experience, one needs a period of reflection to sort through what happened, what does it mean, why it matters, and most importantly, how they can use what they learned and apply to the future.

Another insight is any trip to the “decision lab” of a game is extremely beneficial, especially when combined with reflection. Just like going to the gym, repetitions are good, as Dr. Gary Klein’s work in recognition primed decision-making demonstrated. The more experiences we have, the easier it is for us to draw upon previous experience to assist our decision-making and learning about our decision-making processes. Naturally, not all experiences are transferable or generalizable, however more experiences facilitate creative thinking and problem solving.

Another insight is any trip to the “decision lab” of a game is extremely beneficial, especially when combined with reflection. Just like going to the gym, repetitions are good, as Dr. Gary Klein’s work in recognition primed decision-making demonstrated. The more experiences we have, the easier it is for us to draw upon previous experience to assist our decision-making and learning about our decision-making processes. Naturally, not all experiences are transferable or generalizable, however more experiences facilitate creative thinking and problem solving.

A third compelling insight is wargames are experiential. It is an immersive experience. This is no surprise, as the greats such Dr. Peter Perla often emphasized this as the most important aspect of a wargame. Anecdotally, people learn more by experiencing the topic, vice through a lecture or just by reading it. My real-life example is watching, in real time, a J5 planner ignoring (or selectively not comprehending) the timelines associated with unit deployments from the J4 planner. However, in a wargame, the J5 saw and felt the pain of the unit sail across the vast ocean — turn by turn — and not being in position when it was needed. The J5 planner will never forget that unit was late to need and carry that experience through their entire career. However, staff officers are often dismissive of a staff estimate stating the same timeline. The experience resonates — the truth can’t be ignored or dismissed.

Finally, the wargame experience is ultimately the best “decision lab” for participants. It provides a safe and repeatable space to attempt to solve wicked problems, conduct hypothesis testing, and challenge assumptions. In order to maximize the experience, a period of reflection is required, whether guided or self. Fundamental wargames give us a controlled environment to think about our thinking — we should do it more often! – Steven Sallot

5. From the NATO Wargaming Handbook – Wargaming is a powerful tool. However, it is not always the appropriate tool given the situation. In general, wargaming should be combined with other methods to achieve comprehensive results. In analytical settings, wargaming generates insights that should be evaluated further through other analytic methods. This can and often should be an iterative process, and these analytical campaigns can contain a number of wargames, analytical studies, experiments, simulations, and exercises. Likewise, in an educational and training environment, wargames can assist players to internalize material they are learning and generate insight for instructors on areas that may need more focus. As a general rule, wargaming has more value earlier in these processes, especially in analytic processes, and is generally not suitable as a culminating event in analytical campaigns. Wargames are not validation tools by themselves, but can be valuable parts of validation processes. — LTC(P) Aaron Beam & Richard Goldblatt

5. From the NATO Wargaming Handbook – Wargaming is a powerful tool. However, it is not always the appropriate tool given the situation. In general, wargaming should be combined with other methods to achieve comprehensive results. In analytical settings, wargaming generates insights that should be evaluated further through other analytic methods. This can and often should be an iterative process, and these analytical campaigns can contain a number of wargames, analytical studies, experiments, simulations, and exercises. Likewise, in an educational and training environment, wargames can assist players to internalize material they are learning and generate insight for instructors on areas that may need more focus. As a general rule, wargaming has more value earlier in these processes, especially in analytic processes, and is generally not suitable as a culminating event in analytical campaigns. Wargames are not validation tools by themselves, but can be valuable parts of validation processes. — LTC(P) Aaron Beam & Richard Goldblatt

We hope today’s podcast and post piqued your interest regarding how wargaming can inform us about the Operational Environment and support Professional Military Education. Army Mad Scientist and the Georgetown University Wargaming Society invite you to learn more about this topic at our Game On! Wargaming & The Operational Environment Conference.

What: An in-person conference to explore Wargaming and how it can help the Army better understand the Operational Environment— check out our agenda!

What: An in-person conference to explore Wargaming and how it can help the Army better understand the Operational Environment— check out our agenda!

When: 6-7 November 2024

Where: The Healey Family Student Center, Georgetown University, 3700 Tondorf Road, Washington, DC 20057

Why: To explore new wargaming methods, new ways to incorporate learning into Professional Military Education, and have an open dialogue with wargamers inside and outside the military.

***In order to attend, you must register through Eventbrite — click here now to reserve your seat — access will be limited to registered attendees only!***

Stay tuned to the Mad Scientist Laboratory for conference updates and forward any questions you may have to madscitradoc@gmail.com

In the meantime, check out the following Mad Scientist Laboratory wargaming related content:

Whipping Wargaming into NATO SHAPE and associated podcast, with COL Arnel David

Wargaming: A Company-Grade Perspective, by CPT Spencer D. H. Bates

Taking the Golf Out of Gaming and associated podcast, with Sebastian Bae

“Best of” Calling All Wargamers Insights (Part 1)

Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response (CHMR) Considerations in Wargaming LSCO, Achieving Victory & Ensuring Civilian Safety in Conflict Zones, and associated podcast with Andrew Olson

Brian Train on Wargaming Irregular and Urban Combat

Live from D.C., it’s Fight Night (Parts One and Two) and associated podcasts (Parts One and Two)

Would You Like to Play a Game? Wargaming as a Learning Experience and Key Assumptions Check and “No Option is Excluded” — Using Wargaming to Envision a Chinese Assault on Taiwan, by Ian Sullivan

Using Wargames to Reconceptualize Military Power, by proclaimed Mad Scientist Caroline Duckworth

Gaming the System: How Wargames Shape our Future and associated podcast, with guest panelists Ian Sullivan, Mitchell Land, LTC Peter Soendergaard, Jennifer McArdle, Becca Wasser, Dr. Stacie Pettyjohn, Sebastian Bae, Dan Mahoney, and Jeff Hodges

The Storm After the Flood virtual wargame scenario, video, notes, and Lessons Learned presentation and video, presented by proclaimed Mad Scientists Dr. Gary Ackerman and Doug Clifford, The Center for Advanced Red Teaming, University at Albany, SUNY

Gamers Building the Future Force and associated podcast

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).