“Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the Army’s endeavors primarily manifested as reactive responses rather than proactive prevention measures that could have been particularly successful in mitigating the spread of the virus.”

[Editor’s Note: Now that the great global disruptor COVID-19 appears to be receding in our collective rear-view mirrors, perhaps it’s time to reflect how we as a Nation could better prepare to respond to the next inevitable pandemic. Historically, the U.S. Army served on the frontline in responding to national health emergencies. Today’s submission by guest blogger Tarun Chandrasekar, a TRADOC G-2 eIntern from The College of William and Mary, explores the Army’s historical role and proposes a renewed Army focus on collaborating in international surveillance and building pandemic readiness with our NATO, Quad, and Quad-Plus allies and partners, in addition to supporting our national response. This mission is especially important, given that Global Climate Change is likely to introduce new diseases, many of which will be airborne. Read on to learn more about this hitherto neglected aspect of the Operational Environment and the proactive role the Army could play in helping to mitigate the effects of future outbreaks!]

Scientists have repeatedly warned that extreme, respiratory virus pandemics, like the COVID-19 and 1918 Influenza pandemics, are going to become far more likely in the upcoming decades: with the risk almost increasing threefold. The United States Army has had a long and rich history of being involved in pandemic surveillance and response and can be a crucial stakeholder in the United States government’s (USG) pandemic response.  The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that all major American stakeholders in public health, including the United States Army, should play a crucial role in mitigating and managing the impacts of such global health crises. Moving forward, to better improve pandemic response capabilities, the U.S. Army should reassert its historical domestic role in the United States public health infrastructure by increasing its partnerships with civilian stakeholders and by increasing international cooperation with its allies and partners. These steps will help ensure a faster, streamlined USG response to future pandemics that have the potential to save millions of lives.

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that all major American stakeholders in public health, including the United States Army, should play a crucial role in mitigating and managing the impacts of such global health crises. Moving forward, to better improve pandemic response capabilities, the U.S. Army should reassert its historical domestic role in the United States public health infrastructure by increasing its partnerships with civilian stakeholders and by increasing international cooperation with its allies and partners. These steps will help ensure a faster, streamlined USG response to future pandemics that have the potential to save millions of lives.

The Army’s Historical Role in Pandemic Response

The 1918 Influenza Pandemic was the first major, modern pandemic that the United States Army faced. The H1N1 virus originated from Army encampments in Kansas and wreaked havoc on overcrowded and ill-equipped Army cantonments, inflicting a disproportionately severe toll on military personnel. To make matters worse, young adults, particularly those aged 25-45, bore the brunt of the virus, causing significant disruptions to the Army’s operations during World War I. While the Surgeon General recommended containment measures such as reduced troop movements and quarantines, Army leadership overrode these recommendations out of concern that they would negatively impact combat operations. Consequently, the virus continued to rapidly proliferate infect, and claim the lives of thousands of Soldiers.

The 1918 Influenza Pandemic was the first major, modern pandemic that the United States Army faced. The H1N1 virus originated from Army encampments in Kansas and wreaked havoc on overcrowded and ill-equipped Army cantonments, inflicting a disproportionately severe toll on military personnel. To make matters worse, young adults, particularly those aged 25-45, bore the brunt of the virus, causing significant disruptions to the Army’s operations during World War I. While the Surgeon General recommended containment measures such as reduced troop movements and quarantines, Army leadership overrode these recommendations out of concern that they would negatively impact combat operations. Consequently, the virus continued to rapidly proliferate infect, and claim the lives of thousands of Soldiers.  Surviving troops were significantly weakened and undertrained which may partially explain the higher casualties that American forces experienced during pivotal offensives against the German Empire.

Surviving troops were significantly weakened and undertrained which may partially explain the higher casualties that American forces experienced during pivotal offensives against the German Empire.

The heavy losses incurred because of the H1N1 virus along with fears that the Axis powers were weaponizing it prompted the U.S. Army to adopt a more proactive stance towards pandemic preparedness and prevention out of concern for operations during World War II. The Army played an instrumental role in creating the Board for the Investigation of Influenza and Other Epidemic Diseases, subsequently renamed the Armed Forces Epidemiological Board (AFEB), whose primary focus was to prevent a second influenza pandemic during World War II. This board focused on the development of a subcutaneous vaccine against the influenza virus, fostering collaboration between civilian and military researchers. By 1945, their concerted efforts led to the successful formulation of a vaccine and the standardization of mass immunization methodologies, resulting in the vaccination of millions of military personnel. In addition, AFEB was also instrumental for the standardization of the nation’s public health practices and pandemic response policies. AFEB’s success in averting or minimizing the effects of subsequent pandemics, coupled with the normalization of vaccines, should have been a testament to the significant role of the Army in preventing pandemics. However, the diminished mortality rates and the lessened impact of outbreaks such as the Asian Flu and Hong Kong Flu eroded the perception of pandemics being a  strategic military threat. Additionally, the rise of multilateral health-based institutions like the World Health Organization (WHO) empowered civilian healthcare systems, like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), to assume greater responsibility for managing national influenza programs and setting pandemic response policies — further reducing the need for a military-led pandemic response. The AFEB was disbanded in 1971, which significantly reduced the Army’s role in the USG’s pandemic response.

strategic military threat. Additionally, the rise of multilateral health-based institutions like the World Health Organization (WHO) empowered civilian healthcare systems, like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), to assume greater responsibility for managing national influenza programs and setting pandemic response policies — further reducing the need for a military-led pandemic response. The AFEB was disbanded in 1971, which significantly reduced the Army’s role in the USG’s pandemic response.

COVID-19 Pandemic: Why Change is Needed

While the responsibility of pandemic response has been shifted to civilian health organizations, the Department of Defense (DoD) — ergo, the U.S. Army — is still a significant stakeholder. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, President George W. Bush’s Administration developed a comprehensive National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza, which emphasized the importance of preparedness, communication, surveillance, and containment. This strategy recognized the imperative of coordinated efforts between federal agencies and international partners, particularly in developing nations. It acknowledged that combating the spread of a pandemic necessitates the utilization of all national resources, which explains why the first Bush administration and subsequent administrations have viewed the DoD as a necessary stakeholder. The DoD implemented this strategy by prioritizing the safeguarding of its forces, personnel, and resources, while also fostering international cooperation. The Army has emphasized engaging with developing nations and participating in global health initiatives, such as medical stability operations.

While the responsibility of pandemic response has been shifted to civilian health organizations, the Department of Defense (DoD) — ergo, the U.S. Army — is still a significant stakeholder. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, President George W. Bush’s Administration developed a comprehensive National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza, which emphasized the importance of preparedness, communication, surveillance, and containment. This strategy recognized the imperative of coordinated efforts between federal agencies and international partners, particularly in developing nations. It acknowledged that combating the spread of a pandemic necessitates the utilization of all national resources, which explains why the first Bush administration and subsequent administrations have viewed the DoD as a necessary stakeholder. The DoD implemented this strategy by prioritizing the safeguarding of its forces, personnel, and resources, while also fostering international cooperation. The Army has emphasized engaging with developing nations and participating in global health initiatives, such as medical stability operations.

While the Army has become an integral part of effectively responding to public health emergencies, the COVID-19 pandemic has also exposed deficiencies in the Army’s policies and procedures, necessitating reforms and additional measures to enhance its efficacy in future crises. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the Army’s endeavors primarily manifested as reactive responses rather than proactive prevention measures that could have been particularly successful in mitigating the spread of the virus. During the pandemic, the Army played a pivotal role in supporting civilian authorities and maintaining operational capabilities. It mobilized its resources to provide vital medical supplies, establish hospital centers, and assist with testing and contact tracing. National Guard units played a crucial part in supporting civilian operations across multiple states.

Nonetheless, the Army encountered significant challenges in sustaining its operational readiness throughout the pandemic. Limited access to diagnostic equipment masked widespread transmission of the virus and forced the Army to rely on reactive measures such as mass quarantines. Outbreaks resulted in the cancellation of vital exercises and disrupted troop deployments, potentially affecting the Army’s operational readiness . For example, the Army had to reduce the number of troops that participated in the DEFENDER-Europe 20 exercises.

Interoperability with other segments of the military has also been negatively affected. At the beginning of the pandemic, more than 20% of the USS Theodore Roosevelt’s crew became affected by COVID-19 forcing most of the crew to be furloughed in Guam. To surmount these operational challenges during a pandemic, the Army should assume a more proactive role in pandemic response and fortify its civil-military partnerships. It should prioritize augmenting preventive health measures and preparedness alongside its response efforts. Collaborating with civilian healthcare systems and international partners can facilitate the exchange of expertise, resources, and best practices, further enhancing the Army’s pandemic response capabilities.

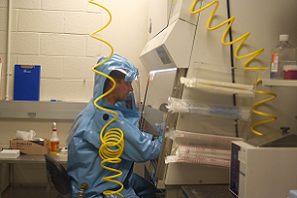

A whole-of-government approach to biodefense is also pivotal in fostering needed multisectoral collaboration. The U.S. Army, through institutions such as the United States Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID), plays a vital role in disease surveillance, risk assessments, and the development of vaccines and countermeasures. It is also, notably, the Army’s only

A whole-of-government approach to biodefense is also pivotal in fostering needed multisectoral collaboration. The U.S. Army, through institutions such as the United States Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID), plays a vital role in disease surveillance, risk assessments, and the development of vaccines and countermeasures. It is also, notably, the Army’s only BSL-4 laboratory facility specialized in handling potent infectious diseases such as the Sars-Cov-2 virus. Despite its crucial role, USAMRIID’s operational capabilities, even before the pandemic, were often hindered by inadequate funding and preparedness. Insufficient biosafety measures and management issues forced the DoD to suspend research activities in 2019 and the failure of the Fort Detrick Steam Sterilization plant further impeded the institute’s research endeavors. Funding from the DoD was withheld until safety guidelines were met, which also diverted attention from critical research activities. Insufficient preparedness led many researchers at USAMRIID to believe that they were ill-prepared to confront the COVID-19 pandemic. One scientist even mentioned that throughout the pandemic they were, “building the plane as they were flying it” showcasing how the pandemic caught USAMRIDD off-guard.

BSL-4 laboratory facility specialized in handling potent infectious diseases such as the Sars-Cov-2 virus. Despite its crucial role, USAMRIID’s operational capabilities, even before the pandemic, were often hindered by inadequate funding and preparedness. Insufficient biosafety measures and management issues forced the DoD to suspend research activities in 2019 and the failure of the Fort Detrick Steam Sterilization plant further impeded the institute’s research endeavors. Funding from the DoD was withheld until safety guidelines were met, which also diverted attention from critical research activities. Insufficient preparedness led many researchers at USAMRIID to believe that they were ill-prepared to confront the COVID-19 pandemic. One scientist even mentioned that throughout the pandemic they were, “building the plane as they were flying it” showcasing how the pandemic caught USAMRIDD off-guard.

The United States Army’s involvement (through the DoD) in Operation Warp Speed also exhibited both successes and shortcomings in its contribution to the whole-of-government approach. The program facilitated the rapid development and approval of COVID-19 vaccines by attempting to reduce the timeline for vaccine development from about ten years to under one year. In this regard, the program was a success as a COVID-19 vaccine was developed and ready for use within a year. However, vaccine distribution was quite ineffective. The number of Americans who received a dose of the vaccine by 2021 was far short of the HHS and DoD’s goals. Logistical and supply chain issues frustrated DoD and Army leaders and the Trump administration largely left vaccine distribution up to individual States, which reduced the effective role that the Army could have played. Dan Diamond noted in his article that by 2021 the distribution phase of Operation Warp Speed was a “deflating end” to a once successful program with only 1/3 of available doses being distributed to Americans during that period.

The United States Army’s involvement (through the DoD) in Operation Warp Speed also exhibited both successes and shortcomings in its contribution to the whole-of-government approach. The program facilitated the rapid development and approval of COVID-19 vaccines by attempting to reduce the timeline for vaccine development from about ten years to under one year. In this regard, the program was a success as a COVID-19 vaccine was developed and ready for use within a year. However, vaccine distribution was quite ineffective. The number of Americans who received a dose of the vaccine by 2021 was far short of the HHS and DoD’s goals. Logistical and supply chain issues frustrated DoD and Army leaders and the Trump administration largely left vaccine distribution up to individual States, which reduced the effective role that the Army could have played. Dan Diamond noted in his article that by 2021 the distribution phase of Operation Warp Speed was a “deflating end” to a once successful program with only 1/3 of available doses being distributed to Americans during that period.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also highlighted the continued need for increased international collaboration, exemplified by the largely absent role of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). NATO, a critical intergovernmental organization, lacked proactive pandemic response capabilities, despite acknowledging the risks of pandemics in its 2010 Strategic Concept. Inadequate resources, including personnel cuts to the Euro-Atlantic Disaster Coordination Center, hindered the alliance’s capacity to coordinate an effective response throughout the pandemic. Consequently, member states were sometimes forced to rely on support from countries traditionally viewed as rivals of NATO. For example, both Italy and Spain had to rely on the People’s Republic of China for N95 masks. In Italy alone, the PRC conducted 13 major operations

The COVID-19 pandemic has also highlighted the continued need for increased international collaboration, exemplified by the largely absent role of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). NATO, a critical intergovernmental organization, lacked proactive pandemic response capabilities, despite acknowledging the risks of pandemics in its 2010 Strategic Concept. Inadequate resources, including personnel cuts to the Euro-Atlantic Disaster Coordination Center, hindered the alliance’s capacity to coordinate an effective response throughout the pandemic. Consequently, member states were sometimes forced to rely on support from countries traditionally viewed as rivals of NATO. For example, both Italy and Spain had to rely on the People’s Republic of China for N95 masks. In Italy alone, the PRC conducted 13 major operations  supplying almost 3.5 million masks compared to the 335,000 masks that NATO member-states provided. Political tensions between NATO member-states have also further strained the alliance’s cohesion, resulting in a lack of coordination and trust that often devolved into infighting key pandemic response policies — especially on vaccine rollouts. The European Union, facing significant criticism for their slow vaccine rollout, enacted export controls on COVID-19 vaccines that impacted the United States’ ability to procure badly needed vaccine doses. These export controls also proved to be a major headache for EU-UK relations as officials accused each other of “vaccine nationalism” causing a diplomatic row between both governments.

supplying almost 3.5 million masks compared to the 335,000 masks that NATO member-states provided. Political tensions between NATO member-states have also further strained the alliance’s cohesion, resulting in a lack of coordination and trust that often devolved into infighting key pandemic response policies — especially on vaccine rollouts. The European Union, facing significant criticism for their slow vaccine rollout, enacted export controls on COVID-19 vaccines that impacted the United States’ ability to procure badly needed vaccine doses. These export controls also proved to be a major headache for EU-UK relations as officials accused each other of “vaccine nationalism” causing a diplomatic row between both governments.

Moving Forward: Avenues for Change in the Army’s Role

The National Biodefense Strategy and Implementation Plan underscored the paramount importance of international cooperation and inter-agency coordination in effectively combating future pandemics. The strategy recognizes that solely domestic actions are insufficient and advocates for a concerted biodefense response in collaboration with international partners. While the likelihood of AFEB being reestablished is small, the U.S. Army must strive to reestablish its historical role as a proactive player in pandemic response and fortify its domestic response capabilities and enhance cooperation with longstanding allies and partners.

The National Biodefense Strategy and Implementation Plan underscored the paramount importance of international cooperation and inter-agency coordination in effectively combating future pandemics. The strategy recognizes that solely domestic actions are insufficient and advocates for a concerted biodefense response in collaboration with international partners. While the likelihood of AFEB being reestablished is small, the U.S. Army must strive to reestablish its historical role as a proactive player in pandemic response and fortify its domestic response capabilities and enhance cooperation with longstanding allies and partners.

The National Biodefense Strategy emphasizes enhancing cooperation and interoperability among diverse stakeholders within the federal government. This provides a robust framework that the Army could use to reassert its historical role in pandemic response and public health. For example, while the Army has established dedicated liaison officers to foster collaboration with civilian health agencies, such as the CDC and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), it should also focus on collaborating with local health departments. Partnerships with local health departments and agencies can be particularly vital given many were overwhelmed during the COVID-19 pandemic — expertise and support from the Army would be invaluable. Developing Joint training exercises and simulations involving military and civilian healthcare professionals could also enhance preparedness and response capabilities in a future pandemic. Likewise, fostering a robust information-sharing partnership with academic institutions, private research organizations, and private sector entities could possibly establish a robust framework that enables these organizations to effectively carry out their research activities during a crisis like a pandemic. This would be similar to the public-private sector partnerships seen in Operation Warp Speed, but maintaining a permanent structure for partnership could be helpful when future pandemics arise. Investing more in U.S. Army research and development programs, particularly by increasing funds for USAMRIID, might enhance knowledge on pandemic prevention, surveillance, and response which increases Army operational capabilities and training of military personnel in the areas of infectious disease control, epidemiology, and public health. Finally, establishing specialized and dedicated units or teams within the U.S. Army that respond to respiratory virus outbreaks, able to rapidly deploy, can provide essential support to civilian authorities during a pandemic. These units could be based on the preventive medicine detachments in an Army Medical Brigade (MED BDE), but would be specifically dedicated to pandemic response.

The Army could also advocate for and foster increased cooperation and coordination on pandemic response with existing military allies, particularly within the Northern Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). While relations between the United States and its European allies can be tenuous, NATO has proven to be a crucial instrument for collaboration and unity during times of crisis. Collaboration with our NATO allies would not only increase our readiness during a global pandemic, but it could also help reduce tensions and increase cooperation during this time of crisis. Collaboration can include Joint research initiatives, sharing of best practices, and mutual support during outbreaks. In particular, the Army could coordinate with its NATO partners and advocate for the expansion of the scope of NATO’s CBRN (Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear) Defense Task Force to include a specific focus on prevention strategies for respiratory virus-based pandemics. Additionally, NATO could conduct multinational military exercises with member-states and partner nations that simulate response scenarios to outbreaks, facilitating interoperability and knowledge exchange among Allied Forces. Finally, given that the funding of the Euro-Atlantic Disaster Response Coordination Centre had been cut in the past, increasing both the funding and its role and activities could be particularly helpful in strengthening cooperation amongst NATO partners.

The Army could also advocate for and foster increased cooperation and coordination on pandemic response with existing military allies, particularly within the Northern Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). While relations between the United States and its European allies can be tenuous, NATO has proven to be a crucial instrument for collaboration and unity during times of crisis. Collaboration with our NATO allies would not only increase our readiness during a global pandemic, but it could also help reduce tensions and increase cooperation during this time of crisis. Collaboration can include Joint research initiatives, sharing of best practices, and mutual support during outbreaks. In particular, the Army could coordinate with its NATO partners and advocate for the expansion of the scope of NATO’s CBRN (Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear) Defense Task Force to include a specific focus on prevention strategies for respiratory virus-based pandemics. Additionally, NATO could conduct multinational military exercises with member-states and partner nations that simulate response scenarios to outbreaks, facilitating interoperability and knowledge exchange among Allied Forces. Finally, given that the funding of the Euro-Atlantic Disaster Response Coordination Centre had been cut in the past, increasing both the funding and its role and activities could be particularly helpful in strengthening cooperation amongst NATO partners.

The Army could also consider enhancing the existing framework for cooperation on disease surveillance within the Quad (United States, Japan, Australia, and India) and Quad Plus (with additional allies and partner nations, such as New Zealand, South Korea, and Vietnam) initiatives. Collaboration within the Quad/Quad Plus might focus on developing a robust system for sharing information, data, and best practices related to pandemic surveillance, early detection, and response. Cooperation can also explore Joint research and development projects on vaccines, therapeutics, and other medical countermeasures to respiratory viruses — leveraging the scientific and technological capabilities of Quad/Quad Plus countries. Member-states of the Quad have already been collaborating on the research and manufacturing of vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic — thus, this existing partnership could easily be scaled to improve interoperability amongst member-states. India could be a vital cornerstone to this effort as it is home to the Institute of Serology, making it one of the largest vaccine manufacturers in the world. As the United States pushes for closer relations and partnerships with India, the Army can use the Quad framework for collaboration to improve our readiness for the next pandemic.

The Army could also consider enhancing the existing framework for cooperation on disease surveillance within the Quad (United States, Japan, Australia, and India) and Quad Plus (with additional allies and partner nations, such as New Zealand, South Korea, and Vietnam) initiatives. Collaboration within the Quad/Quad Plus might focus on developing a robust system for sharing information, data, and best practices related to pandemic surveillance, early detection, and response. Cooperation can also explore Joint research and development projects on vaccines, therapeutics, and other medical countermeasures to respiratory viruses — leveraging the scientific and technological capabilities of Quad/Quad Plus countries. Member-states of the Quad have already been collaborating on the research and manufacturing of vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic — thus, this existing partnership could easily be scaled to improve interoperability amongst member-states. India could be a vital cornerstone to this effort as it is home to the Institute of Serology, making it one of the largest vaccine manufacturers in the world. As the United States pushes for closer relations and partnerships with India, the Army can use the Quad framework for collaboration to improve our readiness for the next pandemic.

If you enjoyed this, read Tarun Chandrasekar‘s TRADOC G-2 eIntern research paper from which today’s post was excerpted here

… then check out the following related Army Mad Scientist content:

Contagion: COVID-19’s impact on the Operational Environment series:

The Insights on Climate Change and the Future of Disease section of The Inevitable Threat: Climate Change and the Operational Environment

Four Models of the Post-COVID World

The COVID Crisis and Beyond: Systemic Biosecurity Lessons to be Learned about Decoherence, Coherence, and HOPE and Heeding Breaches in Biosecurity: Navigating the New Normality of the Post-COVID Future, by proclaimed Mad Scientist Dr. James Giordano and John Wallbank

Persistent Disorder Strikes Back – Implications for Future Joint Force Design, by proclaimed Mad Scientist Jeff Becker

Operation United Assistance: The DoD Response to the West Africa Ebola Virus Epidemic slide deck and video, by CDR Benjamin Espinosa, U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine & Surgery, at the Multi Domain Battle (MDB) In Megacities Conference, hosted by the TRADOC G-2, USARPAC, and the Australian Army, 3-4 April 2018, at Fort Hamilton, New York.

In Urban Sickness and Health — Disasters and the Future of Megacities by Dr. Russell Glenn

>>>>REMINDER: AFGFR Vignette Writing Contest — Our Sister Service partners in the U.S. Air Force (USAF) are proud to present the Air Force Global Futures Report: Joint Functions in 2040, published by Headquarters Air Force A5/7 (aka Air Force Futures). This report is the USAF’s analogue to the U.S. Army Futures Command’s AFC Pamphlet 525-2, Future Operational Environment: Forging the Future in an Uncertain World 2035-2050.

The AFGFR highlights four future operating environments and major implications for the future force. To bring these operating environments to life, Army Mad Scientist is partnering with the Air Force Futures’ Foresight Team to conduct the AFGFR Vignette Writing Contest — based on the report’s four futures and the exploration of the Joint Functions. We are seeking vignettes  with characters that make the future operating environments and associated Joint Functions within come to life!

with characters that make the future operating environments and associated Joint Functions within come to life!

The AFGFR Vignette Writing Contest is open to all — anyone can submit an entry. Entries should be between 1500-2500 words in length, and are due NLT 01 September 2023. To learn more about the contest and how to submit your entry(ies), click >>>> here <<<< and read the contest flyer!

About the Author: Tarun Chandrasekar is a senior who is graduating in August from The College of William and Mary with a Bachelor’s degree in Neuroscience. He is also part of the Global Scholars Program where he has a special interest in the intersection of public health and medicine with national security issues. Tarun is currently an intern at the Department of Defense in the Nuclear and CWMD Policy Office, where he works on biodefense and biothreat response policies.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).