[Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist Laboratory welcomes back returning guest blogger Dr. Russell Glenn, Director, Plans and Policy, TRADOC G-2, with today’s post, revolutionizing our concept of “maneuver” and proposing bold new courses of action to tackle the thorny issues TRADOC is currently addressing in our Are We Doing Enough, Fast Enough? series of virtual events — namely, that our adversaries (both near-peer and non-state actors) recognize U.S. dominance in conventional warfare, and instead seek to shape and achieve their nefarious objectives below the threshold of kinetic conflict using cyber and information operations. Countering our adversaries’ “sub-threshold maneuver” will require a sea change in how we organize and apply our U.S. National Security structure to deter, and failing that, engage our adversaries in this new era of competition, crisis, conflict, and change — Read on! (Please review this post via a non-DoD network in order to access all of the embedded links — Thank you!)]

Building a world-class military is not only expensive. It is a long-term undertaking involving confrontation not only in terms of technology, but also manpower quality, leader development, training, education, logistics, and other components that only collectively and symbiotically constitute a successful warfighting force. Developing these components individually requires years, in some cases decades. Molding them into an effective whole takes many additional years.

Building a world-class military is not only expensive. It is a long-term undertaking involving confrontation not only in terms of technology, but also manpower quality, leader development, training, education, logistics, and other components that only collectively and symbiotically constitute a successful warfighting force. Developing these components individually requires years, in some cases decades. Molding them into an effective whole takes many additional years.

Our near-peer adversaries (Russia and China) are choosing to sidestep U.S. conventional dominance. They seek to compete in fields cheaper to cultivate and maintain — cyber, information, and artificial intelligence among them — buying time in addition to taking advantage of whatever economies this indirect approach provides. We are arguably already at war from their perspective, a war they wish to keep largely devoid of force-on-force confrontation. Time might in fact prove that progress

Our near-peer adversaries (Russia and China) are choosing to sidestep U.S. conventional dominance. They seek to compete in fields cheaper to cultivate and maintain — cyber, information, and artificial intelligence among them — buying time in addition to taking advantage of whatever economies this indirect approach provides. We are arguably already at war from their perspective, a war they wish to keep largely devoid of force-on-force confrontation. Time might in fact prove that progress  in other-than-traditional military domains renders battlefield superiority unnecessary. Achieving war aims without having to directly confront the United States in armed conflict would constitute the acme of success.

in other-than-traditional military domains renders battlefield superiority unnecessary. Achieving war aims without having to directly confront the United States in armed conflict would constitute the acme of success.

Whether in the interest of economy or time, our adversaries will, under some conditions, find it crucial to avoid breaching thresholds that provoke their adversary’s significant use of armed force. Sub-threshold maneuver aspires to do just that. “Maneuver” is not a term chosen lightly here. How the US and its partner nations’ armed forces (and by extension their governments) understand the term goes far in explaining why we remain complacent regarding ongoing wars conducted by means other than combat. Maneuver as  currently defined by the United States military is the “employment of forces in the operational area, through movement in combination with fires and information, to achieve a position of advantage in respect to the enemy.”1 It is in this sense an inherently battlefield construct with little if any application to strategy. US armed forces are arguably the best in the business when maneuver is so narrowly construed. Commendable, but how relevant is this superiority when the conflict space is other than a battleground? The problem is not one of playing baseball while our competitors play soccer. We as world champions have dutifully reported to the stadium while the other team burns the surrounding city. The above definition of maneuver is insufficient other than as applies to our chosen sport, one our competitors choose to play only to the extent it benefits them and then, only at times and places of their choosing. Better to unbind maneuver to lend it value to broader and more elevated challenges.

currently defined by the United States military is the “employment of forces in the operational area, through movement in combination with fires and information, to achieve a position of advantage in respect to the enemy.”1 It is in this sense an inherently battlefield construct with little if any application to strategy. US armed forces are arguably the best in the business when maneuver is so narrowly construed. Commendable, but how relevant is this superiority when the conflict space is other than a battleground? The problem is not one of playing baseball while our competitors play soccer. We as world champions have dutifully reported to the stadium while the other team burns the surrounding city. The above definition of maneuver is insufficient other than as applies to our chosen sport, one our competitors choose to play only to the extent it benefits them and then, only at times and places of their choosing. Better to unbind maneuver to lend it value to broader and more elevated challenges.

A far more relevant understanding conceives of maneuver as “the employment of relevant means to gain advantage with respect to select individuals or groups in the service of achieving desired ends.”2 Thus unbound, maneuver sheds the shackles of applicability to armed force alone. Given this revision of “maneuver,” sub-threshold maneuver becomes “the employment of relevant resources to gain advantage with respect to select  individuals or groups in the service of achieving specified objectives while not triggering an unacceptable response by one or more adversaries.” Such maneuver can, but does not have to, include the use of military capabilities or combat.

individuals or groups in the service of achieving specified objectives while not triggering an unacceptable response by one or more adversaries.” Such maneuver can, but does not have to, include the use of military capabilities or combat.

Limitations on an effective US response

“Aircraft enable us to jump over the army which shields the enemy government, industry, and the people and so strike direct and immediately at the seat of the opposing will and policy. A nation’s nerve system, no longer covered by the flesh of its troops, is now laid bare to attack.“3 — Sir Basil H. Liddell Hart, in Paris: Or, The Future of War, published in 1925

Replace “aircraft” in the above quotation with “disinformation and cyberattacks” and the situation is one we grapple with today. Objectives include undermining confidence in national financial systems, voting processes, and government legitimacy. The decentralized character of the US government and nature of its society make effective response to such threats difficult. An adversary’s sub-threshold employment of capabilities constitutes practice of the indirect approach on a grand scale, one that circumvents the strength of America’s military, thereby marginalizing the primary — arguably the primary — means of guaranteeing the country’s national security interests.

Russia’s successful seizure of the Crimea at the cost of tolerable economic sanctions and a cancelled visit or two is a bargain by any measure. China’s regional economic, assertive diplomatic, psychologically undermining, and supportive military initiatives in the South China Sea address immediate strategic objectives while also setting the stage for further expansion of influence and, perhaps, a future limited but more substantial regional employment of armed force.

Despite the perceptions of many in the West, the use or threatened use of armed force is not essential to waging war..4 It seems trite to quote one of Sun Tzu’s better-known offerings, but I am sure it has already come to mind in many of this post’s readers: “To win one hundred victories in one hundred battles is not the acme of skill. To subdue the enemy without fighting is the acme of skill.”5 Even if present, employment of armed force may assume no more than a subordinate role in relation to other applied means.

As with our consideration of Liddell Hart’s indirect approach, we must look beyond battlefields if we are to appreciate Sun Tzu’s wisdom in the context of the United States’ current strategic challenges. Our competitors’ success in applying the indirect approach via sub-threshold maneuver extends well beyond flying over, flanking, or enveloping forces on terrain. When the objectives include avoiding major armed conflict, the indirect approach requires the orchestration of multiple elements of national power, each of which is an instrument acting in combination with others — the effects of which achieve sought-after goals without exceeding the threshold of an unacceptable response.  The wise competitor maneuvers economic influence, diplomatic initiative, the threat or limited use of armed force, psychological manipulation, cyberattacks, and other means to gain advantage while avoiding over-dependence on any one. Potential supporting activities range widely, from interfering with deployed soldiers’ bank accounts to exacerbating divides between America’s tech giants and government agencies.

The wise competitor maneuvers economic influence, diplomatic initiative, the threat or limited use of armed force, psychological manipulation, cyberattacks, and other means to gain advantage while avoiding over-dependence on any one. Potential supporting activities range widely, from interfering with deployed soldiers’ bank accounts to exacerbating divides between America’s tech giants and government agencies.

Nor are the competitions inherent in war restrained to theaters of war (much less battlefields), unless one accepts that those theaters can extend worldwide and into space. The challenge for the United States is first to recognize this expanded conceptualization of war and, second, to address it despite the constraints of a national security structure too decentralized and otherwise flawed to bring the elements of national power to bear effectively. Constraints in the second case include bureaucratically rigid compartmentalization and absence of a management structure able to overcome that discretization.

The political attractiveness of large, high-profile defense projects further complicates effective US development and employment of the means necessary to compete beyond the battlefield. Congressional legislation skews  defense spending toward these expenditures and in so doing promotes funding for a new fighter jet or tank while relegating cyber, information, counterintelligence, diplomacy, and other initiatives to lesser status. America at present seems hesitant to recognize its ongoing involvement in wars of expanded character. It is also questionable that its current government structure is suitable for responding to the threat.

defense spending toward these expenditures and in so doing promotes funding for a new fighter jet or tank while relegating cyber, information, counterintelligence, diplomacy, and other initiatives to lesser status. America at present seems hesitant to recognize its ongoing involvement in wars of expanded character. It is also questionable that its current government structure is suitable for responding to the threat.

Toward a coherent approach

Leaving adversaries’ sub-threshold maneuver substantially unaddressed fundamentally threatens US national security. The federal government structurally defaults to the Department of Defense as primary guardian of national security. Decentralization of the executive branch below the National Security Council leaves no organization or individual responsible for holistic consideration of the country’s well-being. This makes systematic orchestration of the instruments of national power all but unachievable. The independence of our commercial sector further diffuses security coherency.

The nature of interstate competition is no longer that of the mid-20th century, yet our federal government remains designed for war in which armed force use is preeminent. America’s federal government requires restructuring. Reallocating existing responsibilities and accompanying that reallocation with the necessary resources might offer an acceptable, less dramatic alternative. Regardless of the approach, the end result must provide an organization empowered to manage the elements of national power coherently in an environment in which multifaceted sub-threshold maneuver is the norm. Restructuring (or reallocation) will require dramatic change, e.g., possible consolidation of select congressional committees and replacement of the National Defense Authorization Act and separate Department of State (and other) authorizations with an overarching national security budget.  Control over purse strings will be fundamental to the success. Without it, existing departments and agencies will ignore the dictates of the new oversight organization. The body’s responsibilities would include government-private sector liaison and negotiation of agreements, e.g., with leaders of the major commercial organizations constituting 85% of US cyber capability.

Control over purse strings will be fundamental to the success. Without it, existing departments and agencies will ignore the dictates of the new oversight organization. The body’s responsibilities would include government-private sector liaison and negotiation of agreements, e.g., with leaders of the major commercial organizations constituting 85% of US cyber capability.

A reconsideration of deterrence should also be inherent in US adaptation to the existential threats posed by sub-threshold maneuver. The challenge is more complex than that of nuclear deterrence; the heterogeneous character of such maneuver requires ubiquitous surveillance married to a comprehensive orchestration of multi-departmental proaction and response. Sub-threshold maneuver well executed is multifaceted and symbiotic. When a competitor impedes one or more ways of gaining advantage, other means are brought to the fore in the equivalent of what would be a flanking movement, envelopment, or some form of subterfuge on a physical battlefield. Deterrence therefore requires the same multi-disciplinary, government-private sector, and god’s-eye perspective as do strategies, policies, and national security activities inherent in foiling or executing sub-threshold maneuver. Unlike the case of nuclear deterrence, deterrence as addressed here is made further difficult in that complete denial of use is unrealistic. Information, cyber, and additional capabilities cannot be completely denied other than in rare circumstances. We should therefore view deterrence in terms of its own thresholds: dissuading threat use by establishing and (when appropriate) making known tolerance red lines.

Successfully guaranteeing national security in light of sub-threshold maneuver will be the realm of innovation demanding collective genius. Threats — state or non-state, government, commercial, or some Frankenstein combination of these — will mold existing capabilities and create others new in the service of their objectives. China’s palette of Belt and Road agreements; South China Sea assertiveness; and policies that include bullying vital US partners and America’s own citizens for offenses as varied as speaking out against human rights violations in Hong Kong and barring Huawei telecoms demonstrate the amorphous nature of the means inherent in sub-threshold maneuver.

Successfully guaranteeing national security in light of sub-threshold maneuver will be the realm of innovation demanding collective genius. Threats — state or non-state, government, commercial, or some Frankenstein combination of these — will mold existing capabilities and create others new in the service of their objectives. China’s palette of Belt and Road agreements; South China Sea assertiveness; and policies that include bullying vital US partners and America’s own citizens for offenses as varied as speaking out against human rights violations in Hong Kong and barring Huawei telecoms demonstrate the amorphous nature of the means inherent in sub-threshold maneuver.

They also make clear China’s often indirect approach in the sense of seeking to undermine foundation stones underlying US security by attempting to erode relations with key allies. Meeting these challenges would have stretched the intellectual capacity of even our Founding Fathers. The first step is acknowledging the existence of the already-present threat. While the United States adapts its approach to warfare, our primary threats are adapting their approach to war.

If you enjoyed this post, please read Dr. Glenn’s comprehensive article from which this post was extracted — “The Indirect Approach Lives!…in China and Russia: Sub-threshold Maneuver and the Flanking of US National Security” – which explores in greater detail the Russian and Chinese sub-threshold maneuvers taken to date to out flank the U.S. — published here on our Mad Scientist All Partners Access Network (APAN) site.

Please also see the following related content:

The Convergence: Hybrid Threats and Liminal Warfare with Dr. David Kilcullen and listen to the associated podcast

Content and video from Operational Environment and Conflict Over the Next Decade — our premier webinar in Mad Scientist’s on-going Are We Doing Enough, Fast Enough? series of monthly virtual events -– featuring panelists Dr. T.X. Hammes, National Defense University; Dr. David Kilcullen, Cordillera Applications Group, and Dr. Sean McFate, Georgetown University

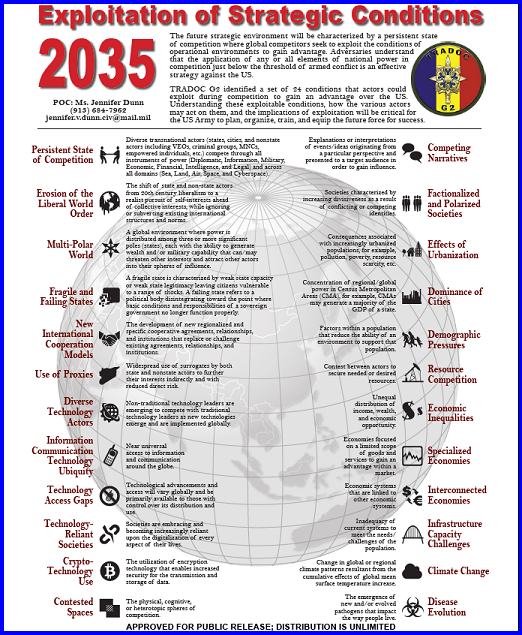

Competition in 2035: Anticipating Chinese Exploitation of Operational Environments

Insights from the Mad Scientist Weaponized Information Series of Virtual Events

China: “New Concepts” in Unmanned Combat and Cyber and Electronic Warfare

“Once More unto The Breach Dear Friends”: From English Longbows to Azerbaijani Drones, Army Modernization STILL Means More than Materiel, by Ian Sullivan

The Erosion of National Will – Implications for the Future Strategist, by Dr. Nick Marsella

Blurring Lines Between Competition and Conflict

>>> REMINDER 1: We will facilitate the final webinar in our Mad Scientist Robotics & Autonomy Series of Virtual Events on Tuesday, 9 February 2021 (1300-1400 EST):

Frameworks (Ethics & Policy) for Autonomy on the Future Battlefield  — featuring Dr. Philip Root (Deputy Director, Defense Sciences Office, DARPA), Alka Patel (Head of AI Ethics Policy at Department of Defense, Joint Artificial Intelligence Center), and Shawn Steene (Senior Force Planner for Emerging Technologies, OSD Strategy and Force Development) — will explore the ethical and policy considerations regarding autonomous systems on the future battlefield. Unmanned robotic and autonomous systems (both individual and swarming) will proliferate across the Operational Environment, presenting a host of opportunities and challenges for the U.S. Army. Join us in addressing these critical issues now so that the Army can incorporate insights into future force development and structuring.

— featuring Dr. Philip Root (Deputy Director, Defense Sciences Office, DARPA), Alka Patel (Head of AI Ethics Policy at Department of Defense, Joint Artificial Intelligence Center), and Shawn Steene (Senior Force Planner for Emerging Technologies, OSD Strategy and Force Development) — will explore the ethical and policy considerations regarding autonomous systems on the future battlefield. Unmanned robotic and autonomous systems (both individual and swarming) will proliferate across the Operational Environment, presenting a host of opportunities and challenges for the U.S. Army. Join us in addressing these critical issues now so that the Army can incorporate insights into future force development and structuring.

In order to participate in this virtual event, you must first register here [via a non-DoD network].

>>> REMINDER 2: We have launched our Mad Scientist Writing Contest on Competition, Crisis, Conflict, and Change to crowdsource the intellect of the Nation (i.e., You!) regarding:

How will our competitors deny the U.S. Joint Force’s tactical, operational, and strategic advantages to achieve their objectives (i.e., win without fighting) in the Competition and Crisis Phases?

How will our adversaries seek to overmatch or counter U.S. Joint Force strengths in future Large Scale Combat Operations?

Review the submission guidelines on our contest flyer, then get cracking brainstorming and crafting your innovative and insightful visions! Deadline for submission is 15 March 2021.

The author thanks colleagues Dr. Mica Hall, Dr. Lester Grau, Gary Phillips, Ian Sullivan, Thomas Switajewski, and Timothy Thomas for insights valuable in constructing this article.

Dr. Russell W. Glenn currently serves as the U.S. Army TRADOC G-2 Director, Plans and Policy, following careers with the Army, think tank community, and on the faculty of the Australian National University. His books include Reading Athena’s Dance Card: Men Against Fire in Vietnam, Rethinking Western Approaches to Counterinsurgency: Lessons from Post-Colonial Conflict, and Trust and Leadership: The Australian Army Approach to Mission Command, released in November 2020. He has just completed a manuscript on disasters in megacities.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

1 DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, Washington, D.C.: US Joint Chiefs of Staff, June 2020, 135.

2 This definition is slightly modified from previous work by the author and colleague Ian Sullivan. See Russell W. Glenn, “Meeting Demand: Making Maneuver Relevant to the 21st Century,” Small Wars Journal (July 5, 2017), https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/meeting-demand-making-maneuver-relevant-to-the-21st-century (accessed December 9, 2020); and Russell W. Glenn and Ian M. Sullivan, “From Sacred Cow to Agent of Change: Reconceiving Maneuver in Light of Multi-Domain Battle and Mission Command,” Small Wars Journal (September 9, 2017), https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/from-sacred-cow-to-agent-of-change-reconceiving-maneuver-in-light-of-multi-domain-battle-an (accessed November 12, 2020).

3 As quoted in Brian Bond, Liddell Hart: A Study of his Military Thought, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1977, 40.

4 This also despite a fair number of “war” definitions that likewise cite the use of armed force.

5 Sun Tzu, The Art of War, trans. and ed. By Samuel B. Griffith, NY: Oxford, 1982, 77.