“Indeed, the ability to adapt is probably the most useful to any military organization and most characteristic of successful ones, for with it, it is possible to overcome both learning and predictive failures. In the interim, however, the cost of such failures will be… high, in terms of blood, treasure, and time.” — Eliot A. Cohen and John Gooch, Military Misfortunes: The Anatomy of Failure in War

[Editor’s Note: In Other People’s Wars, Dr. Brent Sterling provided a longitudinal evaluation spanning the 19th and 20th centuries on what the U.S. military learned from foreign conflicts. Exploring the Crimean, Russo-Japanese, Spanish Civil, and Yom Kippur Wars as use cases, Dr. Sterling identified how effectively the U.S. assimilated key lessons from each of these conflicts and either rapidly adapted across doctrine, organization, training and education, materiel, leadership, personnel, facilities, and policy (DOTMLPF-P); drew erroneous conclusions; or failed to act altogether.

Ian Sullivan sagely pointed out that a “learning organization requires institutional humility, an organizational open mind, and a decisive willingness to ‘disrupt yourselves before you are disrupted.‘” To put it bluntly, an effective organization must overcome its cultural resistance to change — the tyranny of its “old guard“ — and rapidly adapt, or face the ignominy of defeat on the battlefield.

Until recently, the Department of Defense and U.S. Army had organizations dedicated to rapid adaptation — during the long, counter-insurgency wars in  Afghanistan and Iraq, entities such as Joint Improvised Explosive Device Defeat Organization (JIEDDO) and Asymmetric Warfare Group (AWG) rapidly developed and helped scale new capabilities — allowing our Warfighters to overcome rapidly evolving adversaries. These institutions, however, were stood down following the end of these conflicts — despite the enduring requirement to anticipate threat capabilities and rapidly proliferate adaptations to the fielded force.

Afghanistan and Iraq, entities such as Joint Improvised Explosive Device Defeat Organization (JIEDDO) and Asymmetric Warfare Group (AWG) rapidly developed and helped scale new capabilities — allowing our Warfighters to overcome rapidly evolving adversaries. These institutions, however, were stood down following the end of these conflicts — despite the enduring requirement to anticipate threat capabilities and rapidly proliferate adaptations to the fielded force.

In today’s post, the Mad Scientist Laboratory continues its exploration of the Operational Environment on behalf of the Army, examining the key role rapid adaptation plays in the Twenty-first century’s battlespace and how our pacing threat China is embracing this tenet in its drive for modernization — Read on!]

Gaining windows of advantage in enduring Large Scale Combat Operations (LSCO) requires rapid cycles of adaptation. This ongoing process requires the continuous adaptation of organizations, technology, and tactics to exploit fleeting opportunities of advantage over our adversaries. Leaders should strive for organic flexibility — constantly learning and adapting, embracing innovations, and overcoming inherent institutional resistance to change. Such innovations include organizational changes via force tailoring, adapting legacy technologies and operationalizing new technology insertions, and integrating lessons learned into new tactics, techniques, and procedures. This is a constant and dynamic process, as our adversaries are simultaneously watching, probing, learning, and adapting in their own quest for battlefield advantage.

Industrial age research, development, and acquisition processes and traditional State-run Defense Industrial Bases (DIB) may struggle to keep pace with the rapid pace of tactical innovation and adaptation, and the enhanced lethality of 21st century LSCO. In the opening months of its “Special Military Operation,” Russian UAVs were relegated to supporting its Reconnaissance Fires Complex, with finite numbers of Orlan-10 Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) UAVs providing limited targeting support. During this existential fight, however, Ukrainian civilians joined the Ukrainian Armed Forces in rapidly adapting commercial UAVs to support combat operations — innovating ad hoc, field expedient capabilities to find and strike Russian forces. In the ensuing two years, the proliferation of Ukrainian and Russian ISR, Repeater, One-Way Attack (OWA), Top Attack, and First-Person View (FPV) UAVs has resulted in constellations of drones operating over and penetrating behind the front lines in Ukraine. High-altitude UAVs teamed with smaller commercial scout UAVs cue targets for ZALA Lancet Loitering Munitions (LMs) and artillery fires, enabling Russian UAV artillery observers to vastly improve their Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) and resultant fires effects. Russian forces are now able to observe and engage mobile targets in Ukraine’s rear areas – a space that had previously been uncontested. This has created monthly demand signals for tens of thousands of these expendable devices, far outstripping either nation’s DIB production capacity. In response, Russia and Ukraine have mobilized volunteer organizations and private businesses to help meet this demand, crowdsourcing their respective nations’ innovative talent to rapidly converge and integrate technologies to produce and adapt new capabilities.

The resultant transparent battlefield with its democratization of precision fires now available to the individual dismounted infantryman has revolutionized the 21st century battlespace — entrenched  defenses have thwarted combined arms fire and maneuver. Artillery and UAV fires continue to attrite maneuver forces fixed by terrain and bands of trenches and minefields.

defenses have thwarted combined arms fire and maneuver. Artillery and UAV fires continue to attrite maneuver forces fixed by terrain and bands of trenches and minefields.

Overcoming institutional culture to adapt and innovate. Mounting combat losses from UAV-directed artillery fires and precision strike FPV UAVs have forced Russia to adapt its Infantry TTPs from mounted armored assaults to dismounted Storm-Z “human wave” assaults against entrenched Ukrainian defenses. In the fight south of Bakhmut, Russian Airborne (VDV) and Motorized Rifle units demonstrated a much-accelerated rate of adaptation and tactical innovation, including a willingness to learn from best practices exhibited by Private Military Contractor (PMC) Vagner and the UAF. These units’ dismounted squads, along with their Infantry Fighting Vehicles (IFVs), maneuvered to provide mutually supported fires and closely exploited terrain – something not seen in other Russian sectors.

China is watching and learning from Russia’s experience in Ukraine, gleaning and incorporating lessons learned in its quest for advantage over the U.S. Army and the Joint Force. In its endeavor to “build a military ‘system of systems’ that will execute harder, better, and faster than ours,”[i] it is transforming the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Professional Military Education (PME) and culture to develop leaders that can adapt to circumstances. The PLA is actively seeking leaders who are “adaptive and innovative. Specifically, it wants leaders to learn new methods and military developments from other countries, incorporate future technologies that have not yet [been] operationalized, and be more creative. There is also a reasonably new emphasis on finding officers who are… independent and willing to take the initiative on their own (within reason).”[ii]

“The PLA has six regional combat training centers and their national center enabling nearly one-third of their maneuver brigades to conduct rotational training exercises annually” – providing its commanders with the opportunity to conduct tough and realistic training. Zurihe, its largest maneuver training area, “has electronic warfare and cyber ranges… coupled with smoke generators that simulate actual equipment battle damage.“[iii] Its Opposing Forces (OPFOR) replicate U.S. Army capabilities, providing rigorous force-on-force engagements. These live training “crucibles” will help grow the next generation of PLA leaders, adept at Joint multi-domain operations.

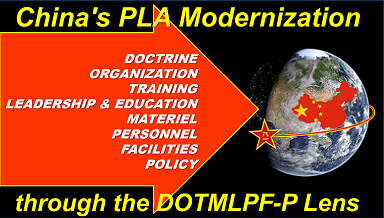

Our pacing challenge continues making strides in modernization across the entire DOTMLPF-P spectrum. China’s industrial base and the PLA’s modernization and restructuring may facilitate quick technology integration during LSCO. The next generation of adaptive and innovative PLA Leaders, combined with the modernized PLA’s sheer mass and depth, could be “capable of, in the words of General Secretary Xi Jinping,  fighting and winning a modern, joint, multidomain war against what the CCP terms “the strong enemy”— a euphemism for the United States.”[iv]

fighting and winning a modern, joint, multidomain war against what the CCP terms “the strong enemy”— a euphemism for the United States.”[iv]

If you enjoyed this post, check out the first two in this Operational Environment series:

Unmanned Capabilities in Today’s Battlespace

The Operational Environment’s Increased Lethality

… as well as the following related content:

The TRADOC G-2‘s Operational Environment Enterprise public facing page, with a plethora of content about our pacing challenge at the China Landing Zone, including ATP 7-100.3, Chinese Tactics, BiteSize China weekly topics, People’s Liberation Army Ground Forces Quick Reference Guide, and our thirty-plus snapshots captured to date addressing what China is learning about the Operational Environment from Russia’s war against Ukraine (note that a DoD Common Access Card [CAC] is required to access this last link).

Three Dates, Three Windows, and All of DOTMLPF-P and “Once More unto The Breach Dear Friends”: From English Longbows to Azerbaijani Drones, Army Modernization STILL Means More than Materiel by Ian Sullivan

China’s PLA Modernization through the DOTMLPF-P Lens, by Dr. Jacob Barton

Insights from Ukraine on the Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Warfare

Other People’s Wars: The US Military and the Challenge of Learning from Foreign Conflicts and associated podcast, with Brent L. Sterling

The Future of Ground Warfare and associated podcast, with Proclaimed Mad Scientist COL Scott Shaw

The Case for Restructuring the Department of Defense to Fight in the 21st Century, by LTC Christopher J. Heatherly

Innovation at the Edge and associated podcast

Strategic Latency Unleashed!, Going on the Offensive in the Fight for the Future, and associated podcast with former Undersecretary of the Navy (and proclaimed Mad Scientist) James F. “Hondo” Geurts and Dr. Zachary S. Davis

Tactical Innovation: The Missing Piece to Enable Army Futures Command, by LTC Jim Armstrong

Mission Engineering and Prototype Warfare: Operationalizing Technology Faster to Stay Ahead of the Threat by The Strategic Cohort at the U.S. Army Tank Automotive Research, Development, and Engineering Center (TARDEC).

Innovation Isn’t Enough: How Creativity Enables Disruptive Strategic Thinking, by Heather Venable

[i] Roderick Lee, “Building the Next Generation of Chinese Military Leaders,” Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, U.S. Air Force Air University, 31 August 2020, p. 135. https://media.defense.gov/2020/Aug/31/2002488091/-1/-1/1/LEE.PDF

[ii] Lee, p. 140.

[iii] Jacob Barton, “China’s PLA Modernization through the DOTMLPF-P Lens,” Mad Scientist Laboratory Blog Post 330, 24 May 2021. https://madsciblog.tradoc.army.mil/330-chinas-pla-modernization-through-the-dotmlpf-p-lens/

[iv] Ian Sullivan, “Three Dates, Three Windows, and All of DOTMLPF-P,” Military Review, January-February 2024. https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/January-February-2024/Sullivan/

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).