[Editor’s Note: Crowdsourcing remains one of Army Mad Scientist’s most effective tools for harvesting ideas, thoughts, and concepts from a wide variety of interested individuals, helping us to diversify thought and challenge conventional assumptions about the Operational Environment.

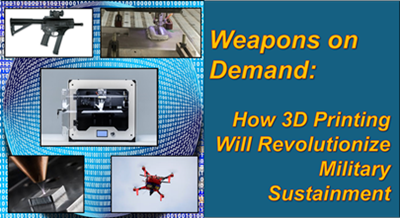

A year ago, we launched our Operational Environment Wicked Problems Writing Contest, seeking to explore how Twenty-first Century warfighting could evolve, given contemporary convergences of battlefield transparency, autonomous systems, and massed and precision fires that have resulted in an increasingly lethal Operational Environment. We asked our readers to address the following topic using either a non-fiction essay, a fictional intelligence (FICINT) story, or a submission incorporating a short FICINT vignette with an accompanying non-fiction essay expounding on the threat capabilities described in the vignette:

A year ago, we launched our Operational Environment Wicked Problems Writing Contest, seeking to explore how Twenty-first Century warfighting could evolve, given contemporary convergences of battlefield transparency, autonomous systems, and massed and precision fires that have resulted in an increasingly lethal Operational Environment. We asked our readers to address the following topic using either a non-fiction essay, a fictional intelligence (FICINT) story, or a submission incorporating a short FICINT vignette with an accompanying non-fiction essay expounding on the threat capabilities described in the vignette:

How have innovations in asymmetric warfare impacted modern large scale and other combat operations, and what further evolutions could take place, both within the next 10 years and on towards mid-century?

Today’s post by Scott Pettigrew was the first runner up in this contest, addressing how 3D printing / additive manufacturing is transforming how non-state actors, like the Rohingya and the Houthis, are equipping their forces with weapons. Since the submission of this post, we’ve seen insurgents in Myanmar use 3D printing to produce Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) and the munitions dropped by them. This capability is also being scaled up to help mitigate supply chain and logistics challenges faced by Ukraine, Russia, China, and the United States and NATO, with the potential of sustaining combat forces at or near the forward edge of battle. “One possible strategy for militaries, even those with robust supply chains, is to employ a hybrid approach, keeping an inventory of the most highly demanded components while using digital records and forward-positioned additive manufacturing equipment to fulfill the remaining needs.” — Read on!]

As the sun set, the dense jungle in northern Rakhine grew increasingly still, the silence broken by the “tree-tree-tree-tree” call of the Asian Green Bee-eater. A group of Rohingya insurgents, their faces hidden and eyes determined, waited patiently. They had received information about a Myanmar army unit approaching, a group of soldiers who had oppressed their people for years and driven many into refugee camps in Bangladesh. As the enemy patrol closed in, Jaivet, a young man of 19 and a former law school student, peered down the barrel of his plastic rifle. The ambush sprung with their foe mere feet away; the thick brush burst open with automatic weapon fire. Desperate Myanmar soldiers scrambled for cover. Some slipped away, but many were not so lucky. As the dust cleared, Jaivet and his fellow Rohingya stepped out on the trail to assess the carnage, gathering up discarded guns, ammunition, and anything else of value they could salvage.

As the sun set, the dense jungle in northern Rakhine grew increasingly still, the silence broken by the “tree-tree-tree-tree” call of the Asian Green Bee-eater. A group of Rohingya insurgents, their faces hidden and eyes determined, waited patiently. They had received information about a Myanmar army unit approaching, a group of soldiers who had oppressed their people for years and driven many into refugee camps in Bangladesh. As the enemy patrol closed in, Jaivet, a young man of 19 and a former law school student, peered down the barrel of his plastic rifle. The ambush sprung with their foe mere feet away; the thick brush burst open with automatic weapon fire. Desperate Myanmar soldiers scrambled for cover. Some slipped away, but many were not so lucky. As the dust cleared, Jaivet and his fellow Rohingya stepped out on the trail to assess the carnage, gathering up discarded guns, ammunition, and anything else of value they could salvage.

The battle you just read is fiction, but the war is real. A coup in Myanmar in 2021 threw the country’s newly elected prime minister in prison. Her arrest and incarceration reignited a long-simmering insurgency against the government. The Rohingya are one of more than 250 ethnic groups challenging the Myanmar junta’s oppression. With a nearly complete ban on the private ownership of firearms, rebel groups in Myanmar rely on smuggling, theft, and scavenging the detritus of battle to arm themselves.1 However, in recent years, the off-again-on-again resistance has found a new source of military equipment and weapons: additive manufacturing, more commonly called 3D (three-dimensional) printing.

Acquiring the needed firepower to resist has been difficult for the Rohingya and other insurgent groups. However, technological advancements have offered a solution, as some Myanmar rebels have begun printing polymer guns to fill the shortfall. One of their favorite 3D-printed firearms is the FGC-92, a semiautomatic pistol that can also adapted to take a 16-inch barrel, both chambered for the 9×19 mm cartridge.3 The FGC-9 print code is widely available across the internet, and the firearm intentionally does not require any parts subject to international firearm controls. Instead of a factory-manufactured gun barrel, the FGC-9 uses hardened 16mm hydraulic tubing.4 The FGC-9 displays admirable durability for a firearm made from polymers and costs a mere $200.5 One example seized by European authorities fired 2,000 rounds before exhibiting reduced performance.6

Traditional manufacturing starts with larger pieces of material such as metal or plastic and removes sections or bends segments until the final shape is revealed. In additive manufacturing, the process begins with nothing and adds material in minute layers that build the final shape over time. Computer-aided design (CAD) software or 3D scanners create a “map” that tells the 3D printer  where to add or “print” each layer, forming a precise three-dimensional shape.7 First-generation 3D printers use polymers as feedstock, but today’s advanced 3D printers can also use a variety of metals such as aluminum, titanium, and stainless steel.8

where to add or “print” each layer, forming a precise three-dimensional shape.7 First-generation 3D printers use polymers as feedstock, but today’s advanced 3D printers can also use a variety of metals such as aluminum, titanium, and stainless steel.8

The Rohingya use firearms made from polymer due to cost, simplicity, and accessibility, but metal guns deliver superior performance. 3D-printed metal firearms first appeared over a decade ago. The first was built by an American company and was modeled after the M1911, the standard .45 caliber semiautomatic pistol adopted by the U.S. Army before WWI.9 The first metal-printed gun used a high-powered laser to fuse layers of small powdered particles of stainless steel and nickel-chromium alloy using selective laser sintering (SLS).10 Using metal instead of polymer is significant because it provides greater performance and durability but at a cost. Entry-level additive manufacturing metal printers are 50 times more expensive than polymer, with machines starting at $10,000 and quickly rising to six figures.11

Larger caliber and high-use weapons need more strength and durability. Barrels that fail to dissipate heat lead to poor accuracy, damage to the barrel, and the possibility for a round to “cook-off,” potentially injuring the crew. To mitigate these issues, U.S. Army Scientists at the Combat Capabilities Development Command Armaments Center invented a method for manufacturing gun barrels using cold spray and wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM) processes.12 The technique involves applying multiple cobalt superalloy, ceramic, and metal coatings, which increases thermal performance and reduces wear.13

Larger caliber and high-use weapons need more strength and durability. Barrels that fail to dissipate heat lead to poor accuracy, damage to the barrel, and the possibility for a round to “cook-off,” potentially injuring the crew. To mitigate these issues, U.S. Army Scientists at the Combat Capabilities Development Command Armaments Center invented a method for manufacturing gun barrels using cold spray and wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM) processes.12 The technique involves applying multiple cobalt superalloy, ceramic, and metal coatings, which increases thermal performance and reduces wear.13

Myanmar rebels are not the only non-state actors resorting to 3D printing. In 2023, the Israel Defense Forces found eight 3D printers in West Bank settlements, along with 3D-printed semiautomatic handguns, short-barreled semiautomatic rifles, and spare parts.14 In Yemen, Houthi rebels use 3D printing for drone production and the missiles being fired into Israel and used to attack commercial shipping in the Red Sea.15

Throughout history, non-state forces have armed themselves through alternative means. Unlike nation-state armies with large-scale industrial foundries and factories, rebels, insurgents, and freedom fighters have often depended on donations from sympathetic countries, purchased weapons on the black market, captured hardware from the enemy in battle, or attacked government-run armories to secure the firepower needed to fight. Before 3D printing, creating a weapons manufacturing capability was expensive and time-consuming, requiring ample factory floor space, specialized equipment, and engineering expertise. With the rise of additive manufacturing, producing entire weapons systems and spare parts has become more accessible and affordable, requiring only a limited budget and average technical knowledge.

Throughout history, non-state forces have armed themselves through alternative means. Unlike nation-state armies with large-scale industrial foundries and factories, rebels, insurgents, and freedom fighters have often depended on donations from sympathetic countries, purchased weapons on the black market, captured hardware from the enemy in battle, or attacked government-run armories to secure the firepower needed to fight. Before 3D printing, creating a weapons manufacturing capability was expensive and time-consuming, requiring ample factory floor space, specialized equipment, and engineering expertise. With the rise of additive manufacturing, producing entire weapons systems and spare parts has become more accessible and affordable, requiring only a limited budget and average technical knowledge.

Additive manufacturing also benefits the largest militaries in the world, including the United States, China, and Russia. These militaries use 3D printing to shorten supply chains, increase sustainment flexibility, and  automate manufacturing. In Russia, engineers have developed a 3D printer that performs 90% of drone production, freeing up workers for other tasks that are difficult to automate, like final assembly.16

automate manufacturing. In Russia, engineers have developed a 3D printer that performs 90% of drone production, freeing up workers for other tasks that are difficult to automate, like final assembly.16

Countries such as Ukraine have militaries that resemble a first world national army in size and composition but lack a robust military-industrial complex to support them. Due to Ukraine’s legacy as a former Soviet Republic and recent donations from many Western countries, its army operates over 40 armored vehicle models and fields nearly 30 different types of artillery in six different calibers.17 Maintaining sufficient repair parts for all models is costly and burdensome. As a partial solution, Ukraine has turned to 3D printing. Shortly after the Russian invasion in February 2022, private companies in Poland sped  3D printers to Ukraine capable of producing medical equipment and drone components.18 Australia also donated three additive manufacturing machines to Ukraine that can produce the metal parts and tools needed to keep its diverse fleet of combat systems operational.19

3D printers to Ukraine capable of producing medical equipment and drone components.18 Australia also donated three additive manufacturing machines to Ukraine that can produce the metal parts and tools needed to keep its diverse fleet of combat systems operational.19

The Ukraine experience has shown that quickly getting 3D printers to where they are needed is crucial. A U.S. startup, Firestorm Labs, recognized the need for rapidly deployable 3D printing technology to manufacture drone components and other critical parts in combat zones.20 Backed by investors like Lockheed Martin, Firestorm Labs’ drone factory fits inside a standard shipping container and can build a complete “Tempest” drone (minus powerplant and flight controls) in nine hours. The Tempest has a seven-foot wingspan, carries a 10 lb payload, and can travel up to 200 miles from the operator.21

Additive manufacturing can also solve issues such as physical weak points that sometimes occur in traditional manufacturing.22 Compared to conventional industrial methods that use rivets or welding to connect parts, 3D printing creates an integrated part with higher structural strength and longer service life. China uses advanced 3D printing to build more robust components for its 5th generation multi-role stealth fighter jet, the FC-31, increasing aircraft reliability and reducing maintenance costs.23 Rostec, a Russian state-owned conglomerate, uses additive manufacturing to strengthen MiG-31 engine components, improving performance and durability.24

The American military’s recent combat history identified an increased need for blast-resistant vehicles. A hull made from welded or bolted-together components creates inherent weak points. To build a vehicle body that’s both  stronger and lighter, the U.S. Army’s Jointless Hull Project commissioned the largest 3D printer in the world, capable of producing seamless objects up to 30 feet long, 20 feet wide, and 12 feet high.25 The new machine is expected to improve production speeds, lower costs, and reduce vehicle weight, improving performance and increased survivability.

stronger and lighter, the U.S. Army’s Jointless Hull Project commissioned the largest 3D printer in the world, capable of producing seamless objects up to 30 feet long, 20 feet wide, and 12 feet high.25 The new machine is expected to improve production speeds, lower costs, and reduce vehicle weight, improving performance and increased survivability.

In addition to producing stronger parts, advanced militaries have recognized additive manufacturing’s ability to shorten supply lines. China’s growing People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is driving a need for more seaborne logistics support. To fill some of the demand, many Chinese warships carry additive manufacturing machines to produce metal parts needed to repair most systems onboard, while underway. Although ships traditionally carry ample spare parts, the ability to manufacture needed components lessens their reliance on distant supply chains.26 As Ren Yalun, a PLAN Officer, put it, “We have benefited from the use of (onboard) 3D printing technology. The 3D printer is like a miniature processing and manufacturing workshop that is able to quickly mend or produce parts, even nonstandard components.”27

Pentagon leaders are optimistic that additive manufacturing can improve long-standing supply chain challenges, particularly in war zones. In 1942, American forces in the Philippines were struggling to survive against an overwhelming Japanese onslaught. The Army made significant efforts to resupply its forces, but the U.S. Navy could not pierce the Japanese blockade. The War Department resorted to privateer blockade runners in a desperate attempt to deliver supplies to besieged GIs, but at least 16 of their craft were sunk.28 A few American submarines managed to reach the remaining Allied strongholds on the Bataan Peninsula and the island of Corregidor, but it was too little, too late. The Pacific Theater was not the only region with contested logistics — In the Atlantic Ocean, German U-boats sunk nearly 3,000 Allied ships, most of them commercial merchant vessels.29 While 3D printing could not have solved the American Soldiers’ ammunition, food, and fuel shortages, a deployed additive manufacturing capability could have reduced some of the need for over-the-shore logistics support.

Not since World War II has America fought an opponent with a robust air and sea threat. However, a 21st-century war in the Indo-Pacific region could challenge American air and naval dominance. The People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) flies over 2,500 combat aircraft, and extensive air defense systems will be difficult to penetrate.30 The PLAN is the largest in the world, floating over 370 vessels and growing rapidly.31 A war in the Indo-Pacific region could provide the U.S. with similar or even more significant supply challenges as WWII.

Additive manufacturing only works if the object you want to print has a corresponding digital file or a digital record representing a three-dimensional shape. The United Kingdom’s Ministry of Defense lists over one million spare parts, but most lack digital records.32 Of the spare parts with a digital record, many are not in the proper format for 3D printing. Recognizing the scale of the problem, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) created a digital repository that allows NATO member nations to store, request, and share technical data packages of 3D printable parts.33

Due to speed, quality, and cost-effectiveness, traditional manufacturing will remain the preferred method for large production runs. However, for small-volume production, the high upfront costs of traditional factories make additive manufacturing an attractive option. Smaller nation-states lacking defense-focused plants may also prefer 3D printing as a secondary source of repair parts. One possible strategy for militaries, even those with robust supply chains, is to employ a hybrid approach, keeping an inventory of the most highly demanded components while using digital records and forward-positioned additive manufacturing equipment to fulfill the remaining needs. This tactic provides maximum flexibility while also reducing supply chain strain.

Additive manufacturing has become a common tool used by non-state actors and large traditional armies. The benefits include the production of hard-to-acquire weapons, shortening supply lines and repair times, and advanced techniques that increase strength and durability. As the technology proliferates, the capability will expand across all forms of conflict, increasing manufacturing and maintenance capability to small, underfunded armies. Large industrial countries like the United States will benefit from employing additive manufacturing capability at home-based factories, within combat theaters, onboard ships, and at remote, isolated outposts. The next significant advancement in 3D printing technology is hard to predict, but what is certain is that future battlefields will be need to be sustained, with additive manufacturing playing a pivotal role.

If you enjoyed this post, check out TRADOC Pamphlet 525-92, The Operational Environment 2024-2034: Large-Scale Combat Operations

Explore the TRADOC G-2‘s Operational Environment Enterprise web page, brimming with authoritative information on the Operational Environment and how our adversaries fight, including:

Our China Landing Zone, full of information regarding our pacing challenge, including ATP 7-100.3, Chinese Tactics, BiteSize China weekly topics, People’s Liberation Army Ground Forces Quick Reference Guide, and our thirty-plus snapshots captured to date addressing what China is learning about the Operational Environment from Russia’s war against Ukraine (note that a DoD Common Access Card [CAC] is required to access this last link).

Our Russia Landing Zone, including the BiteSize Russia weekly topics. If you have a CAC, you’ll be especially interested in reviewing our weekly RUS-UKR Conflict Running Estimates and associated Narratives, capturing what we learned about the contemporary Russian way of war in Ukraine over the past two years and the ramifications for U.S. Army modernization across DOTMLPF-P.

Our Iran Landing Zone, including the latest Iran OE Watch articles, as well as the Iran Quick Reference Guide and the Iran Passive Defense Manual (both require a CAC to access).

Our Running Estimates SharePoint site (also requires a CAC to access), containing our monthly OE Running Estimates, associated Narratives, and the 2QFY24, 3QFY24, 4QFY24, and 1QFY25 OE Assessment TRADOC Intelligence Posts (TIPs).

Then review the following related Mad Scientist Laboratory content addressing the role of 3D printing / additive manufacturing in sustainment:

Sinews of War: Innovating the Future of Sustainment by then MSG Donald R. Cullen, MSG Timothy D. Roberts, MSG Jessica Cho, and MSG Johanny Ortega

The 4th Industrial Revolution, Additive Manufacturing, and the Operational Environment by Jeremy McLain

The Hard Part of Fighting a War: Contested Logistics

About the Author: Scott Pettigrew is an intelligence specialist with TRADOC G-2, where his focus area is China’s People’s Liberation Army, developing doctrine and analytical products to support the Warfighter in training and future operations. Over a 23-year career in the U.S. Army, Scott served in infantry and intelligence assignments at every echelon from Platoon through Army, including a stint with the National Security Agency.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

1 RFA Burmese. 2023. Myanmar enacts Weapons Law aimed at keeping guns away from resistance. May 18. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/junta-weapons-law-05182023164647.html.

2 Pike, Travis. 2022. “Guns Are Being 3D Printed in Myanmar.” The National Interest. https://nationalinterest.org/blog/reboot/guns-are-being-3d-printed-myanmar-199401.

3 DEFCAD. n.d. FGC-9 Mk2 9mm Pistol. https://defcad.com/library/6dfa19fc-f290-4869-959f-04cc1b206006/.

4 Jenzen-Jones, N.R., and Patrick Senft. 2022. FGC-9 3D-printed firearm seized in Western Australia. June 22. https://armamentresearch.com/fgc-9-3d-printed-firearm-seized-in-western-australia/#:~:text=Further%2C%20in%20forensic%20tests%20with,failure%E2%80%94albeit%20with%20deteriorating%20accuracy.

5 Schneider, Ari. 2021. 3D-Printed Guns Are Getting More Capable and Accessible. February 16. https://slate.com/technology/2021/02/3d-printed-semi-automatic-rifle-fgc-9.html.

6 Jenzen-Jones, N.R., and Patrick Senft. 2022. FGC-9 3D-printed firearm seized in Western Australia. June 22. https://armamentresearch.com/fgc-9-3d-printed-firearm-seized-in-western-australia/#:~:text=Further%2C%20in%20forensic%20tests%20with,failure%E2%80%94albeit%20with%20deteriorating%20accuracy.

7 GE. 2023. Additive Manufacturing. https://www.ge.com/additive/additive-manufacturing.

8 Additive Manufacturing. 2024. Additive Manufacturing Materials. https://www.additivemanufacturing.media/kc/what-is-additive-manufacturing/am-materials.

9 Bryant, Ross. 2013. World’s first 3D-printed metal gun successfully fired. November 8. https://www.dezeen.com/2013/11/08/worlds-first-3d-printed-metal-gun-manufactured-by-solid-concepts/.

10 Plafke, James. 2013. The world’s first 3D printed metal gun is a beautiful .45 caliber M1911 pistol. November 7. https://www.extremetech.com/extreme/170574-the-worlds-first-3d-printed-metal-gun-is-a-beautiful-45-caliber-m1911-pistol

11 Kauppila, Ile. 2024. The Best Metal 3D Printers in 2024. April 16. https://all3dp.com/1/3d-metal-3d-printer-metal-3d-printing/.

12 Champagne, Victor, Adam Jacob, Frank Dindl, Aaron Nardi, and Michael Klecka. 2019. Cold Spray and WAAM Methods for Manufacturing Gun Barrels. United States of America Patent US 10,281,227 B1. May 7. https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/f2/44/25/6b78246301fbf4/US10281227.pdf

13 Ibid.

14 IDF Editorial Team. 2023. 3D Printed Weapons Found in Judea and Samaria. https://www.idf.il/en/articles/2023/3d-printed-weapons-found-in-judea-and-samaria/.

15 Horton, Michael. 2023. Yemen’s drone doom loop: A model of instability for fragile states. https://responsiblestatecraft.org/yemen-houthis-drones/.

16 TASS. 2023. Russia creates 3D printer for industrial production of drones. August 1. https://tass.com/defense/1655075.

17 Global Data. 2024. 3D battlefield printing in Ukraine. January 15. https://www.verdict.co.uk/3d-printing-ukraine-battlefield/?cf-view.

18 Feldman, Amy. 2022. Putting 3D Printers To Work In Ukraine’s War Zone. March 31. https://www.forbes.com/sites/amyfeldman/2022/03/31/putting-3d-printers-to-work-in-ukraines-war-zone/?sh=223703645015.

19 Domingo, Juster. 2023. Australian Company Supplies 3D Printers to Ukraine Frontlines. October 3. https://www.thedefensepost.com/2023/10/03/australian-3d-printers-ukraine/.

20 McFadden, Christopher. 2024. US aids shipping container-size 3D-printing drone factories for Ukraine. March 11. https://interestingengineering.com/innovation/startup-develops-3d-printing-drone-factories.

21 Tegler, Eric. 2023. UAS Startup Firestorm’s Ambition To Crank Out Combat Drones Fast, Cheap And En Masse Is A Lesson For DoD. April 27. https://www.forbes.com/sites/erictegler/2023/04/27/uas-startup-firestorms-ambition-to-crank-out-combat-drones-fast-cheap-and-en-masse-is-a-lesson-for-dod/?sh=530ea11d1409.

22 Holmes, Larry R. 2023. Additive Technology Revolutionizes Defense Manufacturing. https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2023/7/6/additive-technology-revolutionizes-defense-manufacturing.

23 Hanaphy, Paul. 2022. 3D Printing Being “Widely Used” in the Production of New Chinese Fighter Jets. December 5. Accessed April 27, 2024. https://3dprintingindustry.com/news/3d-printing-being-widely-used-in-the-production-of-new-chinese-fighter-jets-218192/

24 Hanaphy, Paul. 2022. How 3D Printing Enhanced MIG 31s. February 22. https://3dprintingindustry.com/news/how-3d-printing-enhanced-mig-31s-permit-russia-to-threaten-deployment-of-hypersonic-weapons-over-ukraine-conflict-and-how-to-stop-them-204776/

25 Manufactur3D. 2022. ASTRO America to manage U.S. Army’s new Jointless Hull Project and deliver a hull-scale tool using Metal 3D Printing. June 24. https://manufactur3dmag.com/astro-america-jointless-hull-project-metal-3d-printing/.

26 Metal AM. 2015. Chinese Navy installs Additive Manufacturing systems on warships. January 12. https://www.metal-am.com/chinese-navy-installs-additive-manufacturing-systems-on-warships/.

27 Ibid.

28 Director of the Service, Supply, and Procurement Division War Department General Staff. 1993. Logistics in World War II – Final Report of the Armed Service Forces. Washington D.C.: Center of Military History.

29 Crocker, H.W. 2006. Don’t Tread on Me. New York: Crown Forum. https://archive.org/details/donttreadonme40000croc/page/310/mode/2up.

30 The International Institute for Strategic Studies. 2023. The Military Balance 2023. London: The International Institute for Strategic Studies. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781003400226/military-balance-2023-international-institute-strategic-studies-iiss.

31 U.S. Department of Defense. 2023. Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China. Annual Report to Congress, Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Defense.

32 Davies, Sam. 2024. Additive manufacturing in defence – 5 things we learnt from the 2024 AMADS Conference. March 6. https://www.tctmagazine.com/additive-manufacturing-3d-printing-industry-insights/latest-additive-manufacturing-3d-printing-industry-insights/the-state-of-play-additive-manufacturing-defence/.

33 Ibid.