[Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist Laboratory welcomes back returning guest blogger Ian Sullivan, Special Advisor for Analysis and ISR for the TRADOC G-2, with another insightful and probing post, building upon the observations from his previous post, The Myth of Agincourt and Lessons on Army Modernization. Complementing Mad Scientist’s new “Are We Doing Enough, Fast Enough?” series of virtual events (check out the content and video from our first webinar in this series [via a non-DoD Network]), today’s post pushes this line of query further, using a number of historical military reforms and last year’s conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh to explore the fundamental question: Is the U.S. Army “building the right force, with the right people to prevail over adversaries who have thought long and hard about how to defeat us?” (Please review this post via a non-DoD network in order to access all of the embedded links — Thank you!)]

In July 2019, I wrote a blog post titled “The Myth of Agincourt and Lessons on Army Modernization.” This piece challenged the mythology surrounding this seminal battle, as well as a stream of analysis, which held that the U.S. military was fast becoming the expensive, exquisite force — akin to the French knights at Agincourt — that is vulnerable to modern equivalents of the English longbow, such as drones or cyber-attacks. My article was intended to offer a stark reminder that although the French were indeed defeated in detail, they still won the war, namely because they learned three important lessons and were able to adopt rapid reforms to implement them. Briefly, these lessons were: 1) the need to master the transitions between competition and conflict; 2) the need for better leadership; and 3) the need to effectively modernize their force.1 I argued that these same lessons, which the French learned the hard way, were relevant to the contemporary U.S. Army, as it works through its own efforts to modernize and adapt to the changing character of warfare evident in today’s Operational Environment (OE).

In July 2019, I wrote a blog post titled “The Myth of Agincourt and Lessons on Army Modernization.” This piece challenged the mythology surrounding this seminal battle, as well as a stream of analysis, which held that the U.S. military was fast becoming the expensive, exquisite force — akin to the French knights at Agincourt — that is vulnerable to modern equivalents of the English longbow, such as drones or cyber-attacks. My article was intended to offer a stark reminder that although the French were indeed defeated in detail, they still won the war, namely because they learned three important lessons and were able to adopt rapid reforms to implement them. Briefly, these lessons were: 1) the need to master the transitions between competition and conflict; 2) the need for better leadership; and 3) the need to effectively modernize their force.1 I argued that these same lessons, which the French learned the hard way, were relevant to the contemporary U.S. Army, as it works through its own efforts to modernize and adapt to the changing character of warfare evident in today’s Operational Environment (OE).

As I concluded my initial thoughts on Agincourt, I argued that the conventional myth of the battle, which holds that the English won a resounding victory and ended the dominance of the armored mounted knight, was false, namely because the French won the war. The English were never able to parlay their tactical victory into a war-winning event. They also did not end the utility, or even the dominance, of the knight on the battlefield. That we often believe it did is nothing more than mythology, or perhaps good information operations by an

As I concluded my initial thoughts on Agincourt, I argued that the conventional myth of the battle, which holds that the English won a resounding victory and ended the dominance of the armored mounted knight, was false, namely because the French won the war. The English were never able to parlay their tactical victory into a war-winning event. They also did not end the utility, or even the dominance, of the knight on the battlefield. That we often believe it did is nothing more than mythology, or perhaps good information operations by an  Englishman of the name William Shakespeare, who mastered the art of the narrative. Indeed, several years later, in a lesser known battle at a place called Patay, French knights with better leadership — St. Joan of Arc — decimated a force of English longbowmen. The lesson here is that technological advantage often is fleeting and may not be as powerful as it initially appears on the surface. The longbow, it turns out, was not a silver bullet or a cheap way to ensure dominance.

Englishman of the name William Shakespeare, who mastered the art of the narrative. Indeed, several years later, in a lesser known battle at a place called Patay, French knights with better leadership — St. Joan of Arc — decimated a force of English longbowmen. The lesson here is that technological advantage often is fleeting and may not be as powerful as it initially appears on the surface. The longbow, it turns out, was not a silver bullet or a cheap way to ensure dominance.

The French ignored the threat posed by the longbow for more than 65 years before working to counter it. French knights were slaughtered by the English longbow at Crecy in 1346, Poitiers in 1356, and again at Agincourt in 1415. There was an institutional arrogance on the part of France’s senior commanders who believed that their force and their approach to warfare would prevail. It took the French three terrible defeats to finally get the message that change might be needed. And in the end, this change required modernization across doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership, personnel, facilities, and policy (DOTMLPF-P) before victory in the Hundred Years War would be secured.

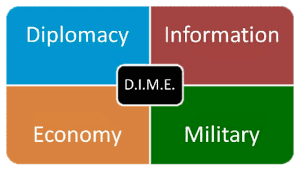

I go on to talk about how the French finally implemented change. They understood that warfare alone could not lead to victory against an adversary  who ably employed an approach across the diplomatic, information, military, and economic (DIME) spheres to hem France in against adversaries on all sides. To win, France had to master competition, crisis, conflict, and change, and victory was not possible until it was able to peel away England’s allies on the continent. Next, France found better leaders, namely when St. Joan arrived on the scene. Having better leadership mattered, and the French won a series of resounding victories before her eventual capture and execution. Finally, the French conducted a hasty, but significant modernization effort, which arrived at DOTMLPF-P solutions to create a more capable force for the final stage of the war.

who ably employed an approach across the diplomatic, information, military, and economic (DIME) spheres to hem France in against adversaries on all sides. To win, France had to master competition, crisis, conflict, and change, and victory was not possible until it was able to peel away England’s allies on the continent. Next, France found better leaders, namely when St. Joan arrived on the scene. Having better leadership mattered, and the French won a series of resounding victories before her eventual capture and execution. Finally, the French conducted a hasty, but significant modernization effort, which arrived at DOTMLPF-P solutions to create a more capable force for the final stage of the war.

Change for France led to ultimate victory in the Hundred Years War, but these lessons were much more painful than they needed to be. And they were painful because France’s military leadership lacked the imagination to recognize the need for change, even in the face of the stinging, and nearly catastrophic losses in men, materiel, and leadership that were suffered as a result of the English successes at Crecy, Poitiers, and Agincourt.

The French experience in this regard is not unique, as a review of history shows us that the most common driver of systemic change within militaries actually comes from defeats. Gaius Marius’ reform of the Roman legions in 107 BCE came in the aftermath of the still fresh memories of Hannibal’s romp through Roman Italy and a series of military stalemates Rome faced in North Africa. The Prussian military reforms of 1807 under the leadership of Gerhard von Scharnhorst, August von Gneisenau, and of course, Karl von Clausewitz, were a direct result of the total defeat of the Prussian Army by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1806. COL-GEN Hans von Seeckt’s reforms of the German Reichswehr laid the foundation for the early successes of the German Wehrmacht in the Second World War, and were the result of a series of DOTMLPF-P-like reforms he implemented after commissioning nearly 60 studies on Germany’s defeat in the First World War.

A more recent example can be found in the experience of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) in the aftermath of their painfully inconclusive war with Lebanese Hizballah in 2006 and the scathing findings of the Winograd Commission. After the release of the report, the IDF instituted a series of “back-to-basics” reforms, which focused largely on doctrine, training, and leader development, and it was rewarded for it by a much better performance during 2008’s Operation CAST LEAD against HAMAS in the Gaza Strip.

In each of these four cases, the Romans, the Prussians, Weimar-era Germany, and post-2006 Israel — as with the French after Agincourt — the military in question discerned that the character of warfare had shifted on them, meaning that they needed to institute changes if they were to find success in future conflicts. What this demonstrates is that an army must become a learning organization if it is to succeed, and that the first step is to overcome the institutional hubris and lack of imagination that often haunts military commanders in the face of developing changes to the character of warfare.

Truly inspired leaders account for these lessons absent the shock to the system provided by a military disaster. However, this is a much harder proposition than it appears. To become this type of learning organization requires institutional humility, an organizational open mind, and a decisive willingness to “disrupt yourselves before you are disrupted.” This is a particularly difficult proposition for the large, conservative bureaucracy that often constitutes a military organization, especially so for one that has not suffered a traumatic defeat, the paramount impetus for change.

In the preceding paragraphs, I referenced the changes implemented by von Seeckt in Weimar Germany. Conversely, the French military in the inter-war years looked to its victory in the  First World War and resisted the revolutionary changes that the Germans were implementing. France doubled down on yesterday’s strategy and compounded the mistake by investing in yesterday’s technology. The result was the infamous Maginot Line.

First World War and resisted the revolutionary changes that the Germans were implementing. France doubled down on yesterday’s strategy and compounded the mistake by investing in yesterday’s technology. The result was the infamous Maginot Line.

This was military modernization for a force that lacked the imagination necessary to understand that the character of war was changing, whose leadership was infected with backward-looking hubris that celebrated past laurels instead of critically looking forward to account for new realities. And we know the story; the Maginot Line barely fired a shot in anger, and the modernized Wehrmacht, fighting a whole new kind of war with a whole new kind of force, accomplished in six weeks what Imperial Germany had failed to do in four years.

The United States Army has been fortunate enough to never truly experience defeat on such a scale, so its need for change has often had different drivers. Yet an honest look at our history reveals that we often have difficulties with first battles — the First Battle of Manassas in the Civil War; Pearl Harbor, the Philippines, and Kasserine Pass in the Second World War; and Task Force Smith in the Korean War — which has forced us to quickly change on the fly.

Furthermore, the U.S. Army has, at times, been able to discern changes to the character of warfare without having suffered a dramatic defeat on the scale of Agincourt or France in 1940. This example is personified in the work achieved at the Army’s Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) in the 1970s and 1980s. Although reacting in part to the difficulties the Army encountered in Vietnam, TRADOC undertook a study of how

the Army would need to adapt in the event of a conflict with the Soviet Union along NATO’s Central Front. The resultant work by GEN William DePuy and GEN Donn Starry looked at the recently-concluded 1973 War between Israel and its Arab neighbors as a paradigm-altering event, and resulted in the creation of the AirLand Battle Doctrine and all of the DOTMLPF-P changes required that would allow the Army to successfully wage its preferred way of war.

Although history never really repeats itself, it does sometimes have a sense of irony, and the Army again finds itself, with a sense of déjà vu, in a place reminiscent of the late 1970s. It is inexorably winding down its counterinsurgency operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, and like TRADOC from the 1970s, its current manifestation also perceives the ground shifting in terms of the character of warfare. Work like the “Russian New Generation Warfare Study” and a series of other analytic work focusing on our pacing threats (China and Russia) again is prompting the Army to change.

As we embark on this drive toward change, we must ponder a critical yet uncomfortable question: Which path will our modernization take? Will we repeat our successful modernization of the late 20th century that positioned the United States for global leadership after the fall of the Soviet Union? Will we be like the French after Agincourt and learn and account for hard lessons that could have been recognized earlier, or will we be more like the English, and place undue faith in our technology and materiel solutions alone? Or perhaps even worse, will we be the French in the Inter-War years and learn the wrong lessons from our successes?

This is a valid question based on the unique experience of the U.S. Army in the aftermath of DESERT STORM, where it maintained a position of dominance for nearly 30 years. This dominance rested on three core assumptions: 1) the US Army is the best equipped in the world; 2) it has the best trained Soldiers and the most dynamic leaders; and 3) its ability to conduct maneuver warfare is unmatched. But as is the case with many successful organizations, assumptions sometimes become core beliefs. Instead of open questions to be continually revalidated, they instead become dogmatic proclamations. Instead of measurable signals of performance, they are viewed as inviolable facts.

And as uncomfortable a question as this may be, it is equally troubling that the answer is not yet clear. Much of the work to date on Army modernization has focused on materiel solutions, bringing new and revolutionary technologies into the force that will significantly enhance our capabilities. But our adversaries are doing the same thing, working on bringing the same technologies into their forces.

Moving just over a year into the future from when I initially contemplated the lessons of Agincourt, we see OE conditions that have arrived faster than we had anticipated, particularly in terms of the rapid changes our pacing threats — China and Russia — have made to more effectively challenge the United States across the spectrum of competition, crisis, conflict, and change. They arguably are more capable than we assessed in our last OE assessment, “The Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Warfare,”2 in terms of their ability to engage the United States in Great Power competition.

The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have only acted as an accelerant to these changes and transformations, and this left us with a profound problem. Our pacing threat rivals are revolutionizing their approaches to Great Power competition and warfare. They are designing military forces and ways of war that challenge the post-Cold War US dominance. Although this challenge initially manifested itself across the materiel domain, it has become clear that our adversaries are actively contesting us across DOTMLPF-P to challenge the three pillars of our post-DESERT STORM dominance. These efforts lead to another question: If the assumptions that underpinned our dominance are being challenged, are we doing enough, fast enough to retain our longstanding advantages?

The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have only acted as an accelerant to these changes and transformations, and this left us with a profound problem. Our pacing threat rivals are revolutionizing their approaches to Great Power competition and warfare. They are designing military forces and ways of war that challenge the post-Cold War US dominance. Although this challenge initially manifested itself across the materiel domain, it has become clear that our adversaries are actively contesting us across DOTMLPF-P to challenge the three pillars of our post-DESERT STORM dominance. These efforts lead to another question: If the assumptions that underpinned our dominance are being challenged, are we doing enough, fast enough to retain our longstanding advantages?

To answer this, the first thing we must do is to take a page from Sun Tzu, who famously wrote “if you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles.” We understand what our adversaries are trying to achieve. They are trying to negate our preferred way of warfare by winning under the threshold of armed conflict, or if it comes to a fight, to design a way of war that makes our strengths irrelevant. Moving forward, we must look at the three pillars of dominance and start treating them as questions to be answered instead of a profession of faith.

Second, we must move beyond the three assumptions and ask ourselves whether our approach is correct. Are we building a force that is capable of overcoming our adversary’s approaches, or do we need to try something else? Are we falling into a trap of their making, or are we driving an approach to warfare that will lead to victory?

And finally, we must remember that while it is essential to bring new capabilities into the force, the materiel advantages we held in the years after DESERT STORM likely will not be maintained. Our pacing threat rivals match us in terms of economic resources and they are increasingly able to innovate on their own. Technological advantages likely will be narrow and perishable.

If we needed any reminders of how these ideas play out on a modern battlefield, we need look no further than the recently ended conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh. Although it is admittedly perilous to derive broad lessons on Great Power competition and conflict from a regional conflict that just ended, this 44-day campaign should serve as a lesson on the Agincourt debate and on how militaries learn and modernize.

The warring parties have been contesting the status of Nagorno-Karabakh since the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the first Nagorno-Karabakh War (1988-1994) ended in favor of Armenia, which carved out the Independent Republic of Artsakh from territory it captured from Azerbaijan. The issue, however, was never properly resolved and remained a frozen conflict for years that simmered with low-level border clashes and periodic escalations, such as a renewed series of clashes in 2016-2017. Clashes re-erupted in September 2020, with Azerbaijan securing a stunning series of successes before Moscow intervened to broker a cease-fire.

This conflict received a great deal of attention, namely because of the successes achieved by the Azerbaijani military, most notably through their creative use of unmanned aerial vehicles — both armed an unarmed — loitering munitions, and expanded use of ground-based fires, including battlefield rockets and ballistic missiles. A great deal of attention was focused on Azerbaijan’s use of drones to target and kill Armenian tanks and armored personnel carriers, which has led some observers to boldly claim that this conflict proves that the era of the tank is over, and that we are on the cusp of a new era in warfare.3

The real reason Azerbaijan won, however, was not just the technology it employed. It was instead because Azerbaijan internalized the lessons it learned in previous defeats and made a variety of changes to its armed forces to shift the military balance. In the earlier conflicts, it was the Armenians who had better equipment, better personnel and leadership, and a better approach to the conflict. In essence, their dominance over Azerbaijan was based on the same assumptions that color U.S. Army thinking in the aftermath of DESERT STORM. As the years progressed, the Armenian military made few changes, essentially following an “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” approach to military modernization. Like the French after the First World War, Armenian hubris and lack of imagination led them to disaster.

For its part, Azerbaijan adapted to change like the French after Agincourt. It paid greater attention to the competition and crisis period by developing an active partnership with Turkey. This alliance provided many real advantages for Baku, which included supplying key technology, such as the Bayraktar TB-2 armed UAV.4 These systems added a whole new dimension to their capabilities. Turkey’s role in the conflict provided Azerbaijan with a degree of cover against Russia and provided the freedom Baku required to launch its offensive.

But Turkey did something else; it helped to train the Azerbaijani military in new tactics and procedures it developed for its own operations in Syria and Libya, involving small teams operating in front of the main line of resistance employing a new reconnaissance-strike capability. In the initial stage of the fight, Azerbaijan and Armenia fought in their traditional manner, focusing on breaking through fixed defenses.5 This proved inconclusive. When the Azerbaijanis shifted to the approaches they learned from Turkey, they suddenly changed the character of the fight and the Armenians were unable to effectively resist them. The result was a decisive victory for Azerbaijan. The Azerbaijanis did in Nagorno-Karabakh what our pacing threats are attempting to do to us; they designed a force that can prevail under conditions they chose and used a way of war that is specifically designed to overcome its adversary. They did not just rely on materiel, but focused on a new approach to warfare matched with soldiers trained and equipped to implement it.6

Herein lies a cautionary tale for the U.S. Army. As an intelligence professional, I am very well versed in the “know your enemy” part of Sun Tzu’s dictum, but admittedly, I spend less time on the “know yourself” aspect. But before the Army moves too far along, I think it is important to ask ourselves which approach are we following on our path to modernization? Are we are trying to revolutionize our approach to warfare, or are we simply trying to modernize a force based on yesterday’s ideas? Is our preferred way of war capable of standing up to our pacing threats’ transformations, or do we need to refine it? Do we consider the post-DESERT STORM pillars to be assumptions that always must be tested or dogma to be held at all cost? We must answer the question “Are we doing enough fast enough?” — but we also must inexorably link that answer to an even more fundamental question: “Are we building the right force, with the right people to prevail over adversaries who have thought long and hard about how to defeat us?”

If you enjoyed this post, read these other insightful posts by Ian Sullivan:

Would You Like to Play a Game? Wargaming as a Learning Experience and Key Assumptions Check

Contagion: COVID-19’s impact on the Operational Environment (Part 4)

The Myth of Agincourt and Lessons on Army Modernization

Making the Future More Personal: The Oft-Forgotten Human Driver in Future’s Analysis

… check your assumptions about Future Force requirements in “Tenth Man” – Challenging our Assumptions about the Operational Environment and Warfare (Part 1) and (Part 2)

… explore the Operational Environment’s breadth and complexity in the near, mid-, and far terms:

Four Models of the Post-COVID World, The Operational Environment: Now through 2028, and The 2 + 3 Threat video

The Future Operational Environment: The Four Worlds of 2035-2050, the complete AFC Pamphlet 525-2, Future Operational Environment: Forging the Future in an Uncertain World 2035-2050, and associated video

… and see what we’ve learned about the Character of Warfare 2035

>>> REMINDER 1: We will facilitate the final webinar in our Mad Scientist Robotics & Autonomy Series of Virtual Events on Tuesday, 9 February 2021 (1300-1400 EST):

Frameworks (Ethics & Policy) for Autonomy on the Future Battlefield  — featuring Dr. Philip Root (Deputy Director, Defense Sciences Office, DARPA), Alka Patel (Head of AI Ethics Policy at Department of Defense, Joint Artificial Intelligence Center), and Shawn Steene (Senior Force Planner for Emerging Technologies, OSD Strategy and Force Development) — will explore the ethical and policy considerations regarding autonomous systems on the future battlefield. Unmanned robotic and autonomous systems (both individual and swarming) will proliferate across the Operational Environment, presenting a host of opportunities and challenges for the U.S. Army. Join us in addressing these critical issues now so that the Army can incorporate insights into future force development and structuring.

— featuring Dr. Philip Root (Deputy Director, Defense Sciences Office, DARPA), Alka Patel (Head of AI Ethics Policy at Department of Defense, Joint Artificial Intelligence Center), and Shawn Steene (Senior Force Planner for Emerging Technologies, OSD Strategy and Force Development) — will explore the ethical and policy considerations regarding autonomous systems on the future battlefield. Unmanned robotic and autonomous systems (both individual and swarming) will proliferate across the Operational Environment, presenting a host of opportunities and challenges for the U.S. Army. Join us in addressing these critical issues now so that the Army can incorporate insights into future force development and structuring.

In order to participate in this virtual event, you must first register here [via a non-DoD network].

>>> REMINDER 2: We have launched our Mad Scientist Writing Contest on Competition, Crisis, Conflict, and Change to crowdsource the intellect of the Nation (i.e., You!) regarding:

How will our competitors deny the U.S. Joint Force’s tactical, operational, and strategic advantages to achieve their objectives (i.e., win without fighting) in the Competition and Crisis Phases?

How will our adversaries seek to overmatch or counter U.S. Joint Force strengths in future Large Scale Combat Operations?

Review the submission guidelines on our contest flyer, then get cracking brainstorming and crafting your innovative and insightful visions! Deadline for submission is 15 March 2021.

The author wishes to thank Dr. Russell Glenn, Dr. Mica Hall, Mr. Ian Kersey, and Mr. Charles Raymond for their thoughtful input and edits.

Ian Sullivan is the Special Advisor for Analysis and ISR for the TRADOC G-2.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

1 For a deeper look at these lessons and how they apply to the Battle of Agincourt and US Army modernization, please see, Ian Sullivan, “The Myth of Agincourt and Lessons on Army Modernization,” Army Mad Scientist Laboratory, 25 July 2019, https://madsciblog.tradoc.army.mil/164-the-myth-of-agincourt-and-lessons-on-army-modernization/

2 TRADOC Pamphlet 525-92, “The Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Warfare,” October 2019, https://adminpubs.tradoc.army.mil/pamphlets/TP525-92.pdf

3 Michael Kofman, “A Look at the Military Lessons of the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict,” Russia Matters: Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, 14 December 2020, https://www.russiamatters.org/analysis/look-military-lessons-nagorno-karabakh-conflict

4 Shaan Shaikah and Wes Rumbaugh, “The Air and Missile War in Nagorno-Karabakh: Lessons for the Future of Strike and Defense,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 8 December 2020, https://www.csis.org/analysis/air-and-missile-war-nagorno-karabakh-lessons-future-strike-and-defense

5 Ron Synovitz, “Technology, Tactics, and Turkish Advice Lead Azerbaijan to Victory in Nagonro-Karabakh,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 13 November 2020, https://www.rferl.org/a/technology-tactics-and-turkish-advice-lead-azerbaijan-to-victory-in-nagorno-karabakh/30949158.html

6 Franz-Stefan Gady and Alexander Stronell, “What the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict Revealed About Future Warfighting,” World Politics Review, 19 November 2020, https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/29229/what-the-nagorno-karabakh-conflict-revealed-about-future-warfighting