[Editor’s Note: In Part I of this series, Dr. Nick Marsella addressed the duty we have to examine our assumptions about emergent warfighting technologies / capabilities and their associated implications to identify potential second / third order and “evil” effects. In today’s post, he prescribes five actions we can embrace both individually and as organizations to avoid confirmation bias and falling into cognitive thinking traps when confronting the ramifications of emergent technologies — Enjoy!]

In part I of my blog post, I advised those advocating for the development and/or fielding of technology to be mindful of the second/third order and possible “evil” effects. I defined “evil” as an unexpected and profound negative implication(s) of the adoption/adaption of a technology and related policy. I also recommended heeding the admonition of Tim Cook, Apple’s CEO, to take responsibility for our technological creations and have the courage to think things through their potential implications – both for the good and the bad.

But even if we as individuals are willing to challenge our assumptions and think broadly and imaginatively, we can still come up short. Why? The answer is due in part to the challenges of prediction and the fact we are human with both great cognitive abilities, but also weaknesses.1

THE CHALLENGES

First, common sense and many theorists remind us that the future is unknowable.2 The futurist Arthur C. Clark noted in 1962, “It is impossible to predict the future, and all attempts to do in any detail appear ludicrous within a very few years.”3 Within this fixed condition of unknowing, the U.S. Departments of Defense and the Army must make choices to determine:

– what capabilities we desire and its related technology;

– where to invest in research and development; and

– what to purchase and field.

As Michael E. Raynor pointed out in his book, The Strategy Paradox, making choices and developing strategies, which include adopting new technology, where the future is unknowable and “deeply unpredictable” either produces monumental successes or monumental failures.4 For a company this can spell financial ruin, while for the Army, it can spell disaster and the loss of Soldiers’ lives and national treasure. Yet, we must also choose a “way ahead” – often by considering “boundaries” – in a sense the left and right limits – of potential implications.

Second, our ability to predict when technology will become available is often in error nor can we accurately determine its implications. For example, in a New York Times editorial on December 8, 1903, it noted: “A man carrying airplane will eventually be built, but only if mathematicians and engineers work steadily for the next ten million years.”5 The Wright Brothers first flight took place the following week, but it took decades for commercial and military aviation to evolve.

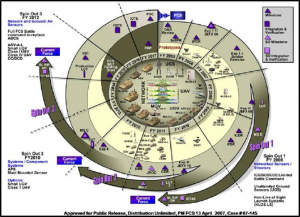

PM FCS, U.S. Army

Each of the services has faced force modernization challenges due to the adoption of technologies that weren’t mature enough; whose capabilities were over-promised; or did not support operations in the envisioned Operational Environment. For the U.S. Army, Future Combat Systems (FCS) was the most obvious and recent example of this challenge – costing billions of dollars and, just as importantly, lost time and confidence.6

Third, in terms of future technology, predictions vary widely. For example, predictions by MIT’s Rodney Brooks and futurist/inventor Ray Kurzweil vary widely to the question – “What year do you think human-level Artificial Intelligence [AI, i.e., a true thinking machine] might be achieved with a 50% probability?” Kurzweil predicts AI (as defined) will be available in 2029, while Brooks is a bit more conservative – the year 2200 – a difference of over 170 years.7

While one can understand the difficulty of predicting when “general AI” will be available, other technologies offer similar difficulties. The vision of the “self-driving” autonomous vehicle was first written about and experimented with in the 1920s, yet technological limitations, legal concerns, customer fears, and other barriers make implementing this capability challenging.

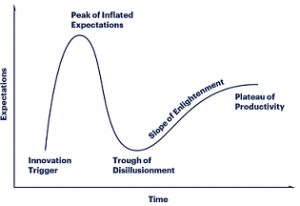

Lastly, as Rodney Brooks has highlighted, Amara’s Law maintains:

“we tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.”8

SECOND, THIRD ORDER AND EVIL EFFECTS

I contend that we either:

– intentionally focus on the positive effects of adopting a technology;

– ignore the experts and those who identify the potential downside of technology; and

– fail to think thorough the short, long, and potentially dangerous effects or dependencies – imaginatively.

We do this because we are human, and more often because we fall into the confirmation bias or other cognitive thinking traps that might affect our program or pet technology. As noted by RAND in Truth Decay:

“Cognitive biases and the ways in which human beings process information and make decisions cause people to look for information, opinion, and analyses that confirm preexisting beliefs, to weigh experience more heavily than data and facts, and then to rely on mental shortcuts and the beliefs of those in the same social networks when forming opinions and making decisions.”9

Yet, the warning signs or signals for many unanticipated effects can be found simply by conducting a literature review of government, think tank, academic, and popular reports (to perhaps include science fiction). This may deter some, given the sheer volume of literature is often overwhelming, but contained within these reports are many of the challenges associated with future technology, such as: the potential for deep fakes, loss of privacy, hacking, accidents, deception, and loss of industries/jobs.

At the national level, both the current and previous administrations published reports on AI, as has the Department of Defense – some more balanced in addressing of issues of fairness, safety, governance, and ethics.10

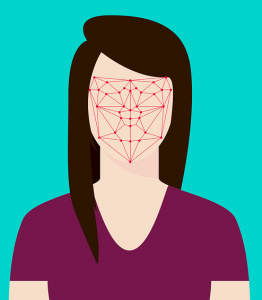

For example, using photo recognition to help law enforcement and others seems like a great idea, yet its use is increasingly being questioned. This past May, San Francisco became the first city to ban its use, and others may follow suit.11 While some question this decision to ban vice impose a moratorium until the technology produces less errors, the question remains – did the developers and policy makers consider if there would be push back to its introduction given its current performance? What sources did they consult?

Another challenge is language. You’ve seen the commercials – “there is much we can do with AI” – in farming, business, and even beer making. While “AI” is a clever tag line, it may invoke unnecessary fear and misunderstanding. For example, I believe for most people equate “robotics” and “AI” with the “Terminator” franchise, raising the fear of uncontrolled autonomous military force overwhelming humanity. Even worse – under the moniker of “AI,” we will buy into “snake-oil” propositions.

Another challenge is language. You’ve seen the commercials – “there is much we can do with AI” – in farming, business, and even beer making. While “AI” is a clever tag line, it may invoke unnecessary fear and misunderstanding. For example, I believe for most people equate “robotics” and “AI” with the “Terminator” franchise, raising the fear of uncontrolled autonomous military force overwhelming humanity. Even worse – under the moniker of “AI,” we will buy into “snake-oil” propositions.

We are at least decades away from “general AI” where a “system exhibits apparently intelligence behavior at least as advanced as a person” across the “full range of cognitive tasks,” but we continue to flaunt the use of “AI” without elaboration.12

SOME ACTIONS TO TAKE

Embrace a learning organization. Popularized by Peter Senge’s The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization (1990), a learning organization is a place “where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning how to learn together.”13 While some question whether we can truly make a learning organization, Senge’s thinking may help solve our problem of identifying 2nd/3rd order and evil effects.

First, we must embrace new and expansive patterns of thinking. Force developers use the acronym – “DOTMPLF-P” as shorthand for Doctrine, Organization, Training, Materiel, Personnel, Leadership, Facilities, and Policy implications – yet other factors might be as important.

For example, trust in automated or robotics systems must be instilled and measured. In one poll, 73% of respondents noted they would be afraid of riding in a fully autonomous vehicle – up 10% points from the previous year.14 What if we develop a military autonomous vehicle or a leader-follower system and one or more of our host nation allies prohibits its use? What happens if an accident occurs and the host population protests, arguing that the Americans don’t care for their safety?

Technologists and concept developers must move from being stove-piped in labs and single-focused to consider the broader view of technological implications across functions.

Embrace Humility. Given that we cannot predict the future and its potential consequences, developers must seek out diversified opinions, and more importantly, recognize divergent opinions.

Embrace the Data. In New York City during World War II, a small organization of some of the most brilliant minds in America worked in the office of the “Applied Mathematics Panel.” In Europe, the 8th U.S. Air Force suffered from devastating bomber losses. Leaders wondered where best to reinforce the bombers with additional armor without significantly increasing their weight to improve survivability. Reports indicated returning bombers suffered gunfire hits over the wings and fuselage, but not in the tail or cockpits, so to the casual observer it made sense to reinforce the wings and fuselage where the damage was clearly visible.

Abraham Wald, a mathematician, worked on the problem. He noted that reinforcing the spots where damage was evident in returning aircraft wasn’t necessarily the best course of action, given that hits to the cockpit and tail were probably causing aircraft (and aircrew) losses during the mission. In a series of memorandums, he developed a “method of estimating plane vulnerability based on damage of survivors.”15 As Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes noted more than 100 years ago, “It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.”16

Additionally, we need to reinforce our practice of performing quality literature reviews to aid in our identification of these issues.

Employ Skepticism and a Devil’s Advocate Approach. In 1587, the Roman Catholic Church created the position of Promoter of the Faith – commonly referred to as the Devil’s Advocate. To insure a candidate for sainthood met the qualification of being canonized, the role of the Devil’s Advocate was to be the skeptic (loyal to the institution), looking for reasons why not to canonize the individual. Similarly, Leaders must embrace the concept of employing a devil’s advocate approach to identifying 2nd/3rd order and evil effects of technology – if not designating a devil’s advocate with the right expertise to identify assumptions, risks, and effects. But creating any devil’s advocate or “risk identification” positions is only useful if their input is seriously considered.

Embrace the Suck. Lastly, if we are serious in identifying the 2nd/3rd order and evil effects, to include identifying new dependencies, ethical issues, or other issues which challenge the adaption or development of a new technology or policy – then we must be honest, resilient, and tough. There will be setbacks, delays, and frustration.

FINAL THOUGHT

Technology holds the power to improve and change our personal and professional lives. For the military, technology changes the ways wars are fought (i.e., the character of war), but it may also change the nature of war by potentially reducing the “human dimension” in war. If robotics, AI, and other technological developments eliminate “danger, physical exertion, intelligence and friction,”17 is war easier to wage? Will technology increase its potential frequency? Will technology create a further separation between the military and the population by decreasing the number of personnel needed? These may be some of the 2nd/3rd order and “evil” effects we need to consider.

If you enjoyed this post, please see Dr. Marsella’s previous post “Second/Third Order, and Evil Effects” – The Dark Side of Technology (Part I)

… as well as the following posts:

– Man-Machine Rules, by Dr. Nir Buras

– An Appropriate Level of Trust

Dr. Nick Marsella is a retired Army Colonel and is currently a Department of the Army civilian serving as the Devil’s Advocate/Red Team for the U.S. Army’s Training and Doctrine Command.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article do not imply endorsement by the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This piece is meant to be thought-provoking and does not reflect the current position of the U.S. Army.

1 Some readers will object to the use of predicting which implies a certain degree of fidelity, but I use the word as defined more loosely as defined by Merriam-Webster dictionary as “to declare or indicate in advance” with synonyms including to foretell, forecast, prognosticate. Retrieved from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/predict#synonyms

2 See: Williamson, Murray. (2017). America and the Future of War: The Past as Prologue. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institute Press, p. 177; Gray, Colin S. (2005, April). Transformation and Strategic Surprise. Carlisle Barracks, PA: Strategic Studies Institute; Gray, Colin S. (2017). What Should the U.S. Army Learn from History? Recovery from a Strategy Deficit. Carlisle Barracks, PA: Strategic Studies Institute

3 Clark, Arthur C. (1962). Profiles of the Future. London, England: Pan Books., p.13

4 Raynor, Michael E. (2007). The Strategy Paradox. New York, New York: Doubleday.

5 Eppler, Mark. (2004). The Wright Way: 7 Problem-Solving Principles from the Wright Brother. New York, New York: American Management Association, 2004. Quote extracted from insert.

6 Department of the Army. (2011). Final Report of the 2010 Army Acquisition Review. Retrieved from: https://www.army.mil/article/62019/army_acquisition_review. See also RAND Report, Lessons from the Army’s Future Combat Systems Program (2012).

7 Rodney Brooks Post – AGI Has Been Delayed, May 17, 2019. Retrieved from https://rodneybrooks.com/agi-has-been-delayed/

8 Brooks, Rodney. (2017, Nov/Dec). The Seven Deadly Sins of AI Prediction. MIT Technology Review, 120(6), p. 79

9 Kavanagh, Jennifer & Rich, Michael D. (2018). Truth Decay: An Initial Exploration of the Diminishing Role of Facts and Analysis in American Public Life. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation (RR 2314).

10 A sample of reports and studies just on AI include: Allen, Greg and Chan, Taniel. (July 2017) Artificial Intelligence and National Security. Harvard Kennedy School – Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs; The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. (2018). Summary of the 2018 White House Summit on Artificial Intelligence for American Industry; Executive Office of the President National Science and Technology Council Committee on Technology. (October 2016). Preparing for the Future of Artificial Intelligence; Department of Defense. (2018). Summary of the 2018 Department of Defense Artificial Intelligence Strategy: Harnessing AI to Advance Our Security and Prosperity; GAO. (2018, June 26). AI: Emerging Opportunities Challenges and Implications for Policy and Research: Statement of Timothy M. Persons, Chief Scientist Applied Research and Methods; Scharre, Paul & Horowitz, Michael C. (June 2018). Artificial Intelligence: What Every Policymaker Needs to Know. Center for New American Security. A simple Google search today using the term “artificial intelligence” produces 55 million results – many of dubious quality.

11 Van Sant, Shannon and Gonzales, Richard. *2019, May 14). San Francisco Approves Ban on Government’s Use of Facial Recognition Technology. NPR. Retrieved from: https://www.npr.org/2019/05/14/723193785/san-francisco-considers-ban-on-governments-use-of-facial-recognition-technology

12 Executive Office of the President National Science and Technology Council Committee on Technology. (October 2016). Preparing for the Future of Artificial Intelligence, p. 7.

13 Garvin, David A. (1993, July August). Building a Learning Organization. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from: https://hbr.org/1993/07/building-a-learning-organization

14 Garner, Greg. (2018, May 22). “Even Millennials are losing confidence in autonomous cars, surveys reveal. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/greggardner/2018/05/22/millennials-self-driving-cars/#62b5aedd2628

15 Syed, M. (2015). Black Box Thinking: Why Most People Never Learn from their Mistakes – But Some Do. New York, New York: Penguin, p. 35-36. Some sources state Wald’s story is embellished. See Bill Casselman’s post the conflict in Wald’s often told story on the American Mathematical Society website. Retrieved from http://www.ams.org/publicoutreach/feature-column/fc-2016-06. Wald’s paper can be retrieved from: https://apps.dtic.mil/docs/citations/ADA091073

16 Doyle, Sir. Arthur. (1891). A Scandal in Bohemia.

17 Von Clausewitz, Carl. On War. Translated Michael Howard and Peter Paret. (Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, p. 88. See https://www.benning.army.mil/MSSP/Nature%20and%20Character/

Good article Nick! Especially like the idea of embracing the idea of learning organization, something the Army as whole could benefit from. Well done.

The problem with all of this is that human thinking is driven by often internalized and personal heuristics and external constraints. The psychology of the individual is constrained by his/her brain and by the organization and ethos in which he/she works. Industry isn’t in business to “red team” their technology. Closest thing I am aware of in our govt to do this was the Congressional Office of Technology Assessment, which was highly successful but was taken down for partisan and anti-science bias reasons in 1995. If you want a function to happen, don’t hope and pray for it to happen, task a person or entity with the function and make them report progress. We need to revive the OTA, now more than ever. We need to task it with this kind of analysis, staff it with ex-military or even current military on a rotational basis, and ensure the people who join the organization are smart, perceptive and not beholden to the traditional “think IN the box” stovepipes and constraints which large organizations like big companies and big governments usually engender. Clarke was a great thinker but the quote cited was wrong. Many people can and do predict the future very well. Not perfectly, but enough to get at what the author is driving at in this piece. Last point is that every person on such an OTA team must have formal education and training on multiple aspects of human psychology either before or after being hired, because only through such a protocol will most people fully understand the scope of what they will be asked to do. Don’t ask a chemist or engineer or scientists in general about the future uses of technology; that person loves to do science and generally has a pro-human, positive outlook on how the tech can be used. You need people who have a deep understanding of the ways people will take what appears to be innocuous developments and use them for nefarious ends. Again to differ with Clarke, all the trouble with social media could have been and probably was predicted by many people whose voices were not heard or sought out. We need to proactively find those voices, not hope their words chance to enter the ears of the right person at the right time.

Although there would appear to be an excess of buzzword hype associated with technology forecasting and acceptance models there is a paucity of commentary on leadership, political circus and budget-confounding limits to transformative advancement. This needs to be addressed in the same context, perhaps for the author’s future installments. It’s good to have reality checks at every step of a project. The project needs to fit into a vision or broader objective whether leadership emphasis on mobility, lethality or other capability. This is true of industrial pursuit or government objectives. Though opportunist advantages should be pursued, the broader goals need to be asserted, with competent challenge and useful commentary – but negative naysayer’s will persist as part of the human condition. There is an art to being a change agent whether positive or antagonist as the devil’s advocate. This art involves the persistent, significant and focused emphasis on positive advancement for principle, in spite of perceived or possible negative use. In fact, unprincipled adversaries – which are common in asymmetric, nontraditional or proxy confrontations – whether traditional force, cyber, nontraditional or future force, persist in attempts to be unpredictable, adaptable, lethal and persistent.

Demonizing technology is shortsighted and potentially lethal since it distracts from the goals of national sovereignty and security. This isn’t the same as accepting conflict resolution success by any means – it is the basis of practical use for man and machine based on the premises, principles, practices and agreements that constitute civil conflict. It is not a one-size fits all, or equal use provenance. Considering consequence is more often accomplished than not. Organizational decisions on uses and their motivation are a distracted difference from consideration of use and consequence by a developer.

At times, the devil’s advocate needs offset by the never sought project champion, an angel’s advocate – it is easier to say “No”, than to imagine, develop, test and field a transformative solution. Perhaps it is sufficient for TRADOC to understand the potential consequence of changes to training, doctrine, policy and performance in context with the objectives of military exercise and prudence. Documenting and considering consequence is worthwhile, but can be damaging if it becomes the polar star leading the vision. As for the future being unpredictable, that is a welcome feature of civilization – and sometimes surprising prognosticators persist. The writings of Verne among others predate developments. The imaginings of yesterday’s fantasies become the stories of tomorrow’s developers along with the unexpected tangents that represent funded industrial research – that research pursuing “dual-use” solutions for endemic problems of the human condition with one specific comment – the solutions must be practical, effective and affordable to make the business case and argument for advancement. Side effects can be missed – or intentionally overlooked including military applications of civil technology. The role of the devil’s advocate – and the documentation of the history of the advancement – with ties to the objective – is a very good thing. The unique aspect of a national security devil’s advocate isn’t in the consequence of ethics and moral uses, it is in the classified sequestration of technology for uniquely military purpose and the consequence of such action. The course of secrecy can generate unintended consequence of greater significance than disruptive science and engineering – which will surface in the international scientific community with or without national security consideration. One might posit that there is no civil technology without “evil” uses and no military tech without “angelic” outcome. Thanks Nick, for a great article with thoughtful content.