[Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist Laboratory welcomes back returning guest blogger Ian Sullivan with another insightful post addressing the relevant lessons that “old school” analog desktop wargames can still teach us about Large Scale Combat Operations with near-peer adversaries in the Twenty-first Century. In challenging our assumptions and reinvigorating our thoughts about the integral relationship between competition, crisis, conflict, and the return to competition, wargaming can be a useful tool in facilitating life-long learning and guarding against that most fatal of flaws in assessing the Operational Environment — the failure of imagination — Read on!]

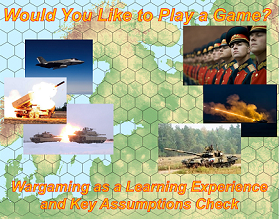

I recently came across an article in War on the Rocks by Dr. James Lacey, entitled “How Does the Next Great Power Conflict Play Out? Lessons From a Wargame.”1 The piece was written a year ago, and details his work at the Marine Corps War College where he had his students simulate a broad global conflict involving the United States dealing with simultaneous outbreaks of conflict in Europe, the Korean Peninsula, and the Taiwan Strait. To run the event, Dr. Lacey used the commercially available Next War series of games published by GMT Games, which simulate a near-future conflict in these areas. The game system is complex, but in Dr. Lacey’s words, offers a reasonable approximation of near future conflict at the operational level of war. Dr. Lacey’s article, and an earlier piece he wrote on wargaming,2 offer a compelling argument for the utility of gaming as a classroom learning tool, allowing students to analyze critical problems and test their solutions, and most importantly, discuss what they learned with a rigorous after-action report (AAR) discussion.

I recently came across an article in War on the Rocks by Dr. James Lacey, entitled “How Does the Next Great Power Conflict Play Out? Lessons From a Wargame.”1 The piece was written a year ago, and details his work at the Marine Corps War College where he had his students simulate a broad global conflict involving the United States dealing with simultaneous outbreaks of conflict in Europe, the Korean Peninsula, and the Taiwan Strait. To run the event, Dr. Lacey used the commercially available Next War series of games published by GMT Games, which simulate a near-future conflict in these areas. The game system is complex, but in Dr. Lacey’s words, offers a reasonable approximation of near future conflict at the operational level of war. Dr. Lacey’s article, and an earlier piece he wrote on wargaming,2 offer a compelling argument for the utility of gaming as a classroom learning tool, allowing students to analyze critical problems and test their solutions, and most importantly, discuss what they learned with a rigorous after-action report (AAR) discussion.

Dr. Lacey’s work appealed to me on many levels. First off, I’ve had a life-long fascination with wargames, starting with my pre-teen purchase of the legendary Avalon Hill game Squad Leader, and working my way through a number of different games, I found that I most particularly enjoyed games that focused on future conflicts. As I played them, I was not anchored by history — which I loved — in trying to solve the complex problem they posited. A number of games from the 1980s and early 1990s, such as Victory Games NATO: The Next War in Europe, Flashpoint: Golan, the Fleet-series of games, Gulf Strike, and Aegean Strike, as well as the Game Designer’s Workshop Assault series of games, along with contemporary writings — some fiction, like Tom Clancy or Harold Coyle, and some more intellectual, such as the great work of Sir John Hackett — set my lifelong interest in defense/security issues and set my career ambition to work as an intelligence analyst.

Twenty years later, and I’m doing what I always wanted to do and am still playing wargames. The only difference is that most of the time, I get paid to play them! I’ve been involved in Department of Defense wargames dating back to the mid-1990s, when I began my career with the Navy, and now, I routinely get the opportunity to play in games and experiments for the Army, where we look to learn something about a capability, concept, or doctrine. Dr. Lacey’s excellent article reminded me of something important; namely that  wargaming, more than anything else, is a thought exercise. It allows us to think about and experience problems in different ways. For example, as an intelligence officer, I almost exclusively think about the “red” side of the game, which is the nomenclature for the

wargaming, more than anything else, is a thought exercise. It allows us to think about and experience problems in different ways. For example, as an intelligence officer, I almost exclusively think about the “red” side of the game, which is the nomenclature for the  adversary. I rarely get to think about “blue” or the friendly forces, except as an object of red actions. We can do more than test; we can actually use games routinely as a means of individual learning, and for me, to check some key assumptions.

adversary. I rarely get to think about “blue” or the friendly forces, except as an object of red actions. We can do more than test; we can actually use games routinely as a means of individual learning, and for me, to check some key assumptions.

My current assignment places me in a position to oversee elements of the Army’s Operational Environment (OE), which, simply put, is the environment in which the Army will have to operate, fight, and win, focusing as part of Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) on the present through 2028. The newly formed Army Futures Command takes the OE into the deeper future. Those of us who work to understand, assess, and analyze the OE spend a great deal of time thinking about the next fight. What will it look like? How will technology affect it? How will our potential adversaries prepare for it? How might they fight it? Some of the assessments we made regarding these key questions are found in TRADOC Pamphlet 525-92, The Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Warfare.3 These questions form a baseline Army leaders can use to center their own thoughts about the type of force we need to develop, particularly at a time where the entire Department of Defense is shifting away from counterinsurgency operations that marked the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and toward renewed large-scale combat operations and an era of Great Power competition, crisis, conflict, and change.

TRADOC Pamphlet 525-92, The Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Warfare.3 These questions form a baseline Army leaders can use to center their own thoughts about the type of force we need to develop, particularly at a time where the entire Department of Defense is shifting away from counterinsurgency operations that marked the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and toward renewed large-scale combat operations and an era of Great Power competition, crisis, conflict, and change.

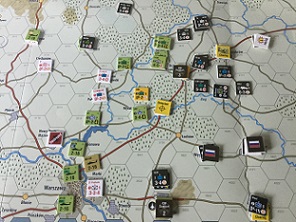

One of the keys to good analysis always is to check your assumptions. There are many ways to do this, but recently, after reading Dr. Lacey’s work, I wanted to try something a bit different. I purchased a copy of GMT’s Next War: Poland, which postulates a conflict between Russia and NATO in the Baltic States and Poland, and wanted to test some of the assumptions we made about near-future conflict. I wanted to use wargaming, not to learn in a classroom, but to focus my own thoughts and views, and hopefully challenge my biases. I also wanted the chance to think a bit more about the “blue” side of the game. I did not intend to use the experience in the Prussian Kriegsspiel manner, to prepare for a war, but instead as means to make me better at my job of understanding what modern warfare might entail. So with my wife’s permission, I was able to clear the big table in our Florida Room and play through Next War: Poland.

Before I get into some of what I think I learned, I must note that I played the game solitaire, which admittedly takes away some of the fog and friction of warfare. Still, the game itself offers enough random chance and outcomes to create unanticipated situations, which allowed me to test some of our underlying assumptions. For example, although I understood my thinking for both sides, die rolls mattered, and presented critical challenges and opportunities to my plans for both sides. A successful strike by Special Operations Forces (SOF), or an inability to detect an inbound air strike, provided a degree of randomness that, at least in part, enhanced the solitaire experience. Also, understanding the power of the AAR process, after each turn, I wrote a detailed AAR of what happened in the game and posted it on a Facebook Group on modern wargaming. This process added a great deal of value to my gaming experience, and I received some fabulous feedback, thoughts, and criticisms along the way from the group’s members. I focused not so much on the outcome, but, in the words of Matthew Kirschenbaum, on the “in-game experience and the after-the-fact analysis and discussion,”4 which I think I successfully enabled through my social media engagement. Indeed, the combination of the gaming and the crowd-sourced feedback mechanism significantly added to the experience and helped me confront my assumptions and biases head on.

The Fight:

And finally, before I delve into lessons, I first need to detail the course of the conflict. The war began in the fall, with a Russian invasion of all three Baltic States and Poland. Belarus sided with Russia, and contributed to the attack. The Russians had some very early success in the Baltic States, but were a bit bloodied in the process. It took Russia about five days to occupy the Baltic States before it was able to turn its full attention on Poland. NATO was relatively well-prepared for the conflict, and had significant air power ready and available on D-day. Most importantly, thanks to solid indications and warning, the United States Army had a strong presence in Poland prior to the conflict. In addition to the standard Europe-

And finally, before I delve into lessons, I first need to detail the course of the conflict. The war began in the fall, with a Russian invasion of all three Baltic States and Poland. Belarus sided with Russia, and contributed to the attack. The Russians had some very early success in the Baltic States, but were a bit bloodied in the process. It took Russia about five days to occupy the Baltic States before it was able to turn its full attention on Poland. NATO was relatively well-prepared for the conflict, and had significant air power ready and available on D-day. Most importantly, thanks to solid indications and warning, the United States Army had a strong presence in Poland prior to the conflict. In addition to the standard Europe- based forces of the 173rd Airborne Brigade, the 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment, and a Europe-based US rotational HBCT — in this case, the 2nd BCT of the 3rd Infantry Division — the entire 82nd Airborne Division and the 1st BCT of the 101st Air Assault Division were on hand in the crisis period.

based forces of the 173rd Airborne Brigade, the 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment, and a Europe-based US rotational HBCT — in this case, the 2nd BCT of the 3rd Infantry Division — the entire 82nd Airborne Division and the 1st BCT of the 101st Air Assault Division were on hand in the crisis period.

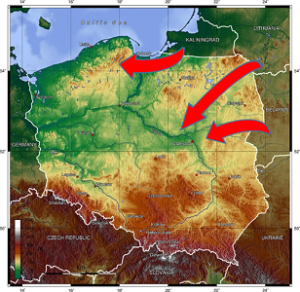

The Russian advance on Poland came along three axes of advance. The first came out of Belarus, attempting to advance on the Warsaw area. The second pushed westward out of the Suwalki Gap, trying to force a breakout between the Masurian Lakes and the Narew River, which, if successful, could have enveloped Warsaw. The third was an advance southward out of the Kaliningrad Exclave, designed largely to threaten Poland’s ports and potentially breakthrough toward the German border. The fighting was intense, and the war lasted about 20-odd days (8 turns, with each turn representing about 2-3 days.)

NATO was fairly successful in the air early on, and was able to significantly reduce the power of the Russian Aerospace Force, and, more importantly, target Russia’s formidable integrated air defense system (IADS.) In took NATO less than 10 days to win Air Superiority, and once they achieved it, they never lost it. The IADS lasted a bit longer, but once down, NATO had a major advantage. Russia’s best success against NATO airpower occurred through ballistic and cruise missile strikes and SOF raids against NATO airbases, but Russia quickly expended its magazines (by day six) for only a moderate result.

NATO maritime forces had a mixed success, largely because I did not play them particularly well. NATO successfully reinforced Bornholm Island, and eventually recovered Gotland Island, which Russia seized in an early air assault. NATO fought a swirling naval battle in the southern Baltic Sea, which destroyed Russia’s Baltic Sea Fleet, but inflicted serious losses on NATO’s maritime forces, including the outright destruction of a German surface action group.

The fight on the ground was very brutal. The Polish Army and the early arriving U.S. Army formations did what they could to stem the initial Russian advance and buy time for the rest of NATO to mobilize. The game has an Article 5 rule, and NATO declared it early, meaning that NATO ground forces appeared quickly (about 4 days into the fight).

The U.S. and Poland made good use of the terrain, which offered several river lines to defend, and cities and towns that simply could not be effectively bypassed, and instead had to be defeated in detail. This was particularly true for the southernmost advance toward Warsaw and the northern advance out of Kaliningrad. NATO initially lacked the combat power to effectively do more than hold a line and buy time, but NATO reinforcement eventually evened the odds. The northern Russian advance was contained around Day 10.

The fight around the Masurian Lakes was a bit more dynamic. The Russians did achieve a breakthrough across the Narew River and managed to push two brigades through a gap in the NATO lines before they were contained by Allied forces. The tide turned around Day 10. NATO was able to use the arrival of the rest of the 101st Air Assault Division to conduct a divisional air assault, which trapped two Russian brigades against the Narew River and shattered the Russian advance. With enough NATO formations in the line, the Alliance went on a general offensive, pushing the Russians back on all fronts.

Russia attempted to turn the tide, first through a series of chemical warfare attacks and then through tactical nuclear strikes. These attacks were costly to NATO—destroying a US carrier battlegroup, an amphibious ready group that  embarked a Marine Expeditionary Unit, and the headquarters of the US 3rd Infantry Division, and severely mauling two German brigades that were threatening a breakthrough toward Kaliningrad. But with its combat power shattered, Russia had little choice but to seek a ceasefire. The war ended with NATO forces right along the Kaliningrad Border, and driving on Belarus, with the way to reclaim the Baltic States open.

embarked a Marine Expeditionary Unit, and the headquarters of the US 3rd Infantry Division, and severely mauling two German brigades that were threatening a breakthrough toward Kaliningrad. But with its combat power shattered, Russia had little choice but to seek a ceasefire. The war ended with NATO forces right along the Kaliningrad Border, and driving on Belarus, with the way to reclaim the Baltic States open.

Lessons Learned:

So what did I learn? The first thing is that I repeated the mistake that most Army wargames and wargamers make – I started with the conflict phase, and did not really concern myself with competition or crisis. These broad concepts  involve whole-of-government/ whole-of-nation issues and very complex interactions across the Diplomatic, Information, Military, and Economic (DIME) spheres, which, admittedly, are beyond the scope of the game, but which, in reality, are the most critical aspect of Great Power interaction in the 21st Century. I made no effort to deter conflict or achieve the political ends of either Russia or NATO; I did not attempt to “win without fighting” as Russia would, relying on broad information operations and diplomacy to separate the

involve whole-of-government/ whole-of-nation issues and very complex interactions across the Diplomatic, Information, Military, and Economic (DIME) spheres, which, admittedly, are beyond the scope of the game, but which, in reality, are the most critical aspect of Great Power interaction in the 21st Century. I made no effort to deter conflict or achieve the political ends of either Russia or NATO; I did not attempt to “win without fighting” as Russia would, relying on broad information operations and diplomacy to separate the  United States and NATO internally and from each other, nor did I make any effort to have the United States or NATO deter the conflict. Fortunately, the game itself takes care of some of this by offering three separate scenarios to play. The first is Strategic Surprise, which essentially means that the United States and NATO failed in Competition and Crisis, and were ill-prepared for an initial Russian advance. The second is Tactical Surprise, which postulates a general success by the United States and NATO in this period; it means that “blue” had some warning of the attack and had improved its pre-game position with additional “boots on the ground.” The final option is Extended Buildup, which simulates a Russian failure in Competition and Crisis, with a fully-prepared NATO ready for their initial thrust.

United States and NATO internally and from each other, nor did I make any effort to have the United States or NATO deter the conflict. Fortunately, the game itself takes care of some of this by offering three separate scenarios to play. The first is Strategic Surprise, which essentially means that the United States and NATO failed in Competition and Crisis, and were ill-prepared for an initial Russian advance. The second is Tactical Surprise, which postulates a general success by the United States and NATO in this period; it means that “blue” had some warning of the attack and had improved its pre-game position with additional “boots on the ground.” The final option is Extended Buildup, which simulates a Russian failure in Competition and Crisis, with a fully-prepared NATO ready for their initial thrust.

I chose to play Tactical Surprise, for no real reason other than that it was the middle option. However, a lesson learned early on is that Competition and Crisis clearly matter, and the choice that I made on how these two critical phases played out had more impact on the game than anything I did in the Conflict phase. In essence, my decision to choose the Tactical Surprise scenario really was the conclusion of a Competition and Crisis phase that ended at least as moderately successful for the United States and NATO. As the game began to play out, I quickly realized that the early arrival of some US formations meant that Russia would be unable to effect a general breakthrough. It was dicey for a time, but as more NATO formations arrived, it  was clear: Had the Russians and Belarusians not encountered what ended up as a very stout defense by elements of the Polish Army and forward-deployed U.S. Army formations along the Polish frontier with Belarus and the border with Kaliningrad, they likely would have made it to the gates of Warsaw. So although I did not actively play it, the Competition and Crisis periods, which are replete with information operations, cyber iterations, diplomacy, and a crucial intelligence confrontation – seeking to both confuse the adversary, and see through their intentions to provide indications and warning – were the decisive moment of the conflict.

was clear: Had the Russians and Belarusians not encountered what ended up as a very stout defense by elements of the Polish Army and forward-deployed U.S. Army formations along the Polish frontier with Belarus and the border with Kaliningrad, they likely would have made it to the gates of Warsaw. So although I did not actively play it, the Competition and Crisis periods, which are replete with information operations, cyber iterations, diplomacy, and a crucial intelligence confrontation – seeking to both confuse the adversary, and see through their intentions to provide indications and warning – were the decisive moment of the conflict.

The second lesson I learned is that NATO’s advantage clearly came from having a multi-domain capable force. Russia actively contested all domains, but NATO did it better, largely because it could more effectively converge multi-domain effects. This was particularly true once NATO had claimed air superiority. When Russia went on the offensive, it was ably supported by its significant fires capabilities, resident in the game as headquarters units, artillery brigades, and rocket artillery brigades. Russia was able to use attack helicopters and some close air support, but NATO’s edge, in number and type of fighters, quickly nullified that advantage. When NATO finally reduced Russia’s IADS and contained its advance, NATO could provide air, maritime, cyber/electronic warfare, and space support (although these latter two categories were abstracted by the game) to critical engagements.

The second lesson I learned is that NATO’s advantage clearly came from having a multi-domain capable force. Russia actively contested all domains, but NATO did it better, largely because it could more effectively converge multi-domain effects. This was particularly true once NATO had claimed air superiority. When Russia went on the offensive, it was ably supported by its significant fires capabilities, resident in the game as headquarters units, artillery brigades, and rocket artillery brigades. Russia was able to use attack helicopters and some close air support, but NATO’s edge, in number and type of fighters, quickly nullified that advantage. When NATO finally reduced Russia’s IADS and contained its advance, NATO could provide air, maritime, cyber/electronic warfare, and space support (although these latter two categories were abstracted by the game) to critical engagements.

I was reminded time and again of the centrality of geography and terrain. Poland and Lithuania offer difficult terrain for modern combat. The multiple rivers – which run not just north-south, but also in some cases, east-west – the lakes, highlands, and marshes are difficult country for mechanized and motorized units. Additionally, the game modelled the problem of internally displaced persons on the battlefield, slowing the ability of forces to move through the throngs of refugees attempting to flee the battlespace. As a result, the initial Russian advance was slow, and had to follow major roadways for much of the early part of the fight. NATO was able to destroy several bridges early on, and used airpower to interdict movement. The other  complicating factor was that the roadways used by the Russians led to countless towns, cities, and built-up urban areas, which NATO was able to use as defensive bastions. Because of the geography, it was difficult for Russia to bypass all of these strongpoints, which bought NATO more time to bring forces forward and severely degraded the Russian spearhead forces. The early fight was a war of attrition, and the losses were eye-opening.

complicating factor was that the roadways used by the Russians led to countless towns, cities, and built-up urban areas, which NATO was able to use as defensive bastions. Because of the geography, it was difficult for Russia to bypass all of these strongpoints, which bought NATO more time to bring forces forward and severely degraded the Russian spearhead forces. The early fight was a war of attrition, and the losses were eye-opening.

This led to another key lesson learned: Modern conflict between similarly equipped Great Powers is exceptionally lethal. The ability to mass fires was critical to the initial Russian success, and then for NATO, as they eventually seized the initiative back and went over to the offensive. The fight for the air was difficult, although NATO routinely prevailed in air-to-air engagements, namely on the strength of its fifth generation F-22s and F-35s. NATO’s most significant losses in the air occurred at the hands of the Russian IADS, and in the tactical  air defenses inherent in Russia’s maneuver formations. Russia lost more than 70 percent of its allotted airpower during the conflict. The game did allow some degree of simulation of multi-domain operations, and various sensors were able to stimulate and see potential targets for a wide range of strike assets, which included land-based (artillery, missiles, and Special Operations Forces), sea-based (cruise missiles, and even some close naval gunfire), and air-launched ordnance. The ground fight was especially difficult. Russia lost more than 20 brigades and NATO lost about ten (including forces targeted by nuclear strikes). This also does not count the many units that suffered severe losses and continued on with reduced capabilities. These losses were staggering, and, realistically, were unsustainable by either side. Most critical engagements on the ground were multi-domain in nature, with fires—mostly artillery and rockets for Russia, and mostly attack helicopters and close air support for NATO—significantly aiding the ground combat. The game did not really simulate cyberwarfare, although apparently a subsequent addition to the game has added rules for this capability. It would be interesting to play it again with those rules in effect.

air defenses inherent in Russia’s maneuver formations. Russia lost more than 70 percent of its allotted airpower during the conflict. The game did allow some degree of simulation of multi-domain operations, and various sensors were able to stimulate and see potential targets for a wide range of strike assets, which included land-based (artillery, missiles, and Special Operations Forces), sea-based (cruise missiles, and even some close naval gunfire), and air-launched ordnance. The ground fight was especially difficult. Russia lost more than 20 brigades and NATO lost about ten (including forces targeted by nuclear strikes). This also does not count the many units that suffered severe losses and continued on with reduced capabilities. These losses were staggering, and, realistically, were unsustainable by either side. Most critical engagements on the ground were multi-domain in nature, with fires—mostly artillery and rockets for Russia, and mostly attack helicopters and close air support for NATO—significantly aiding the ground combat. The game did not really simulate cyberwarfare, although apparently a subsequent addition to the game has added rules for this capability. It would be interesting to play it again with those rules in effect.

Of particular interest to me as a member of TRADOC was the importance of human capital – of the quality and effectiveness of the Soldiers and Leaders who comprised the armies on the map. The game demonstrates the importance of troop quality by allowing for shifts in the combat results table. U.S. forces and certain NATO elements have a very high troop quality, which in comparison to a typical Russian unit, allowed for a column shift in favor of the  US/NATO in most engagements. This meant that if Russia had a 3:1 advantage in combat power, US/NATO excellence in leadership development, training, and education meant that the fight would be resolved instead on even terms. And when combined with other shifts and modifiers for defending in strong terrain – the presence of rotary-wing attack aviation, or fast-mover close air support – NATO was able to prevail, or hold on in the face of much greater enemy numbers. Early on, this was one of the most critical aspects of the conflict, when the three BCTs of the 82nd Airborne Division successfully held off the main advance out of Belarus, and even more apparent when a task force of the 2-3 BCT and the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry held off the main avenue of the Russian advance out of Kaliningrad for days. The quality of the unit mattered greatly, and when matched with the smart defense of key terrain, proved highly formidable in the face of great numeric disadvantage.

US/NATO in most engagements. This meant that if Russia had a 3:1 advantage in combat power, US/NATO excellence in leadership development, training, and education meant that the fight would be resolved instead on even terms. And when combined with other shifts and modifiers for defending in strong terrain – the presence of rotary-wing attack aviation, or fast-mover close air support – NATO was able to prevail, or hold on in the face of much greater enemy numbers. Early on, this was one of the most critical aspects of the conflict, when the three BCTs of the 82nd Airborne Division successfully held off the main advance out of Belarus, and even more apparent when a task force of the 2-3 BCT and the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry held off the main avenue of the Russian advance out of Kaliningrad for days. The quality of the unit mattered greatly, and when matched with the smart defense of key terrain, proved highly formidable in the face of great numeric disadvantage.

Finally, the game reminded me of the dangers of entering into conflict with a nuclear-armed opponent. As its offensive power waned, Russia turned first to chemical weapons, and when they proved inconclusive, tactical nuclear weapons. I also had NATO conduct one nuclear strike in response. The game has an interesting feature, where at the end of any phase where a side uses  nuclear weapons, the player must roll a die to determine if the tactical nuclear use escalates to a general strategic exchange. The odds increase for every tactical nuclear weapon used. By the fifth strike, I actually rolled low, which meant that the game was over and humanity lost. I conveniently took what I called a “strategic mulligan” and ignored the result, namely because I wanted to play a few more turns. But the lesson to me was chilling, and the dangers of Great Power conflict came very clearly into focus for me.

nuclear weapons, the player must roll a die to determine if the tactical nuclear use escalates to a general strategic exchange. The odds increase for every tactical nuclear weapon used. By the fifth strike, I actually rolled low, which meant that the game was over and humanity lost. I conveniently took what I called a “strategic mulligan” and ignored the result, namely because I wanted to play a few more turns. But the lesson to me was chilling, and the dangers of Great Power conflict came very clearly into focus for me.

Conclusion:

Thus ended my experience with fighting Next War: Poland. I cannot claim to have learned any grand strategic lesson or operational approach that will fundamentally shift US defense policy or Army doctrine. Furthermore, as a career civilian intelligence officer who has never served in uniform (but did complete the Army War College’s Combined/Joint Force Land Component Commander Course), I cannot even claim to have fought this conflict particularly well. In fact, my social media AAR pointed out several key mistakes I made, moves I botched, and opportunities I missed. They also pointed out where my biases may have led me to take certain ill-considered actions.

Furthermore, there clearly were elements of the game that diverged from what reality might be. For example, NATO’s very quick entry into the war was made due to a die roll; in reality, the Article 5 question likely would be a drawn out, and potentially messy political process that was beyond the scope of the game. Some aspects of the game oversimplified what in reality are terribly difficult and complex command and control and interoperability questions. Additionally, some of the actions I took in the game clearly have no bearing in what would occur in a real military operation. And finally, the end of the game was completely artificial, in that the political realities of the nuclear strikes were not really apparent to the game, as was the fact that I ignored the catastrophic escalation that occurred. This game represented a short, relatively decisive conflict; reality might prove otherwise. But again, I did not intend this to be a Kriegsspiel; I meant it as a thought exercise.

In that light, I think the effort was a success in that it made me think about certain things that I often do not get a chance to consider. It allowed me to walk in the steps of the blue commander and see the world through his/her eyes. It allowed me to consider and ruminate on what I have thought, written, and briefed on the OE and the threat in a new way by challenging some assumptions, helping to confirm others, and offering new data points to consider. Much of what we concluded in TRADOC Pamphlet 525-92 appeared in the game: The lethality of modern combat, the effects of fires, and the multi-domain nature of the fight were all there. But it also reminded me in stark detail that some of the more timeless aspects of warfare we did not necessarily address in that document, such as the importance of terrain, and really, the critical truth that the quality of the personnel had a much more glaring impact on the results than did the actual materiel capabilities of the units. Finally, it brought into further clarity that the most important issue surrounding the game was something I did not even really think about or play out, but which was defined by the scenario; the centrality of the Competition and Crisis periods.

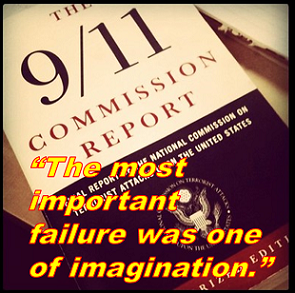

Most of all, I think I demonstrated that wargaming should be something that all of us involved in thinking about the next fight do from time to time. To me, this journey of individual learning is just as important as the large games and experiments we play at various war colleges to test concepts, doctrine, and capabilities. The individual learning process I experienced was well worth the cardboard casualties and map board mistakes I made along the way. Although I was “old school” in my approach, moving cardboard armies around a paper  map, the opportunities to play such games online could only expand their availability and utility. The 9/11 Commission concluded that of all the failures that occurred in allowing al-Qa’ida to conduct their attacks on New York City and Washington, the most lethal was a failure of imagination. In this sense, gaming can help us guard against this failure and imagine what a future conflict might look like and add a new approach to the life-long leaning process required of a career intelligence officer.

map, the opportunities to play such games online could only expand their availability and utility. The 9/11 Commission concluded that of all the failures that occurred in allowing al-Qa’ida to conduct their attacks on New York City and Washington, the most lethal was a failure of imagination. In this sense, gaming can help us guard against this failure and imagine what a future conflict might look like and add a new approach to the life-long leaning process required of a career intelligence officer.

If you enjoyed this post, check out the following:

>>> REMINDER: The Mad Scientist Initiative will facilitate our next webinar on  Thursday, 12 November 2020 (1100-1200 EST):

Thursday, 12 November 2020 (1100-1200 EST):

The Future of Unmanned Maritime Systems – featuring proclaimed Mad Scientist Mr. Sam Bendett, Researcher and Consultant, CNA; Mr. Kelvin Wong, Editor: Unmanned Maritime Systems at Janes; and Mr. Montrell Smith, Assistant Program Manager, Advanced Autonomy Capabilities, Unmanned Maritime Systems, U.S. Navy.

In order to participate in this virtual event, you must first register here [via a non-DoD network].

Ian Sullivan is the Assistant G-2, ISR and Futures, at Headquarters, TRADOC.

Thanks to Dr. Mica Hall (TRADOC G-2) and Mr. Gary Philips (TRADOC G-2, Retired) for their thoughtful and helpful review of this article.

- Disclaimer: All views expressed in this post are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

1 James Lacey, “How Does the Next Great Power Conflict Play Out? Lessons From a Wargame,” War on the Rocks, 22 April 2019.

2 Lacey, “Wargaming in the Classroom: An Odyssey,” War on the Rocks, 19 April 2016.

3 TRADOC Pamphlet 525-92, “The Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Warfare,” October 2019.

4 Matthew Kirschenbaum, “War, What is it Good For? Learning From Wargaming,” Play the Past, 16 August 2011.

Great article! I can honestly say off-duty wargaming gave me the critical thinking and understanding of operational art, that a very sometimes power-point focused Professional Military Education could not. It is heartening to see that the use of wargames in the military and the national security scene have jumped out of obscurity in the last ten years. A little less amygdala, a little more pre-frontal cortex.

Most important statement made in this post is “…I repeated the mistake that most Army wargames and wargamers make – I started with the conflict phase, and did not really concern myself with competition or crisis.”

It is unlikely we will engage in a kinetic fight with Russia or China. Not impossible, but not likely. Hundreds of factors in assessing probability but odds maybe 20%?

It is 100% certain we will, because we are in it right now, fight in that WOG/DIME so-called competition “phase”, which is really just war by “nonexplosive” means. Sun Tzu preached this literally ages ago, yet we see little discussion about it and there seems to be little action on our part.

More content in this forum on this issue would raise the issue to its appropriate place in the discourse. Author of this post admitted it himself, as anyone who has seen or participated in a wargame for decades has seen – it is a very common and very repeated mistake to ignore the “competition” issues.

Thanks so much for the comment. I agree 100 percent with you that the Competition and Crisis periods are the decisive points in this era of Great Power rivalry, particularly where both of our pacing threats focus on the idea of using whole-of-government/whole-of-nation approaches so that they can “win without fighting.” I tried to make the point that my decision to play the middle course, tactical surprise scenario really was the most important decision I made during the entire game. Although I did not “play” the seminal Competition and Crisis periods, I did at least assume a result. The most important lesson I learned is that the game would have gone a whole lot different if I played the Strategic Surprise scenario. I do believe the Army and DoD as a whole (my opinion, mind you) is focusing more heavily on these critical periods. But it is a problem that likely cannot be solved by DoD alone. It will require a whole-of-government approach in which DoD plays an important, but perhaps not the leading role.

If you’re interested, Dr. Russell Glenn and I wrote an article on the subject titled “Why the US Government is No Longer Capable of Providing National Security”, which ran in THE NATIONAL INTEREST in March 2018 which addresses the exact issue you raise.

FYSA… shared by a Mr. Brian D. Wieck:

“U.S. defense strategists and policymakers have the perennial challenge of developing capstone documents that can coherently articulate and guide how the U.S. Department of Defense will deliver and maintain combat-credible military forces to deter war and provide national security in alignment with national strategy. These forces must be ready to fight and prevail should deterrence fail against a variety of threats in an evolving and uncertain global security environment, and they must be able to do this with acceptable risks – both in the present against today’s threats and in the future against threats that might emerge. Key audiences for these capstone documents include defense planners, programmers, budgeters, managers, analysts, and policymakers who support the development and management of forces that can be postured and employed in alignment with a given defense

strategy to accomplish objectives.

Against this backdrop, RAND researchers developed Hedgemony, a wargame designed to teach U.S. defense professionals how different strategies could affect key planning factors in the trade space at the intersection of force development, force management, force posture, and force employment. The game presents players, representing the United States and its key strategic partners and competitors, with a global situation, competing national incentives, constraints, and objectives; a set of military forces with defined capacities and capabilities; and a pool of periodically renewable resources. The players are asked to outline their strategies and are then challenged to make difficult choices by managing the allocation of resources and forces in alignment with their strategies to accomplish their objectives

within resource and time constraints.

A short video featuring interviews with U.S. defense professionals that played Hedgemony and the RAND researchers that developed it is available here.”

https://www.rand.org/pubs/tools/TL301.html

Ian Sullivan! Greetings! Long time no see. Congrats on your superb career success!

I’m delighted to learn you’re a wargamer. Failure of due diligence on my part to learn that back 20 years ago.

You might remember ONI’s Simulation-Based Analysis & Training (SimBAT) program, which ONI still has me doing. In fact, planning is underway to reinvigorate the program in keeping with the shift from GWoT to GPC. We have not elevated ops to the very robust ‘Next War’ series, however, in part because their focus is so continental where here, of course, we train in naval warfare/systems analysis.

I’m impressed you tackled such a high-end sim. I played ‘Korea 1995′ (the progenitor of the series) a good bit back when Pyongyang was getting feisty in the 90s but have yet to break out, sit down, and master the newer editions. Tip o’ th’ hat to you and Lacey’s Marine students.

One of the primary complaints about ‘Next War: Poland’ is that it missed the entire Baltic flank, where Russia actually could conceivably move. A Poland campaign is just a ‘sandbox’ as the expression goes, a scenario that, however interesting analytically, falls well outside the frame of plausible projection. (Nothing wrong with that; for my next SimBAT trick I’m going to have the USN and SovNav duke it out in the Med in an escalation to hot war during the Oct 73 Arab-Israeli War.) However, I really hope GMT puts out a Baltic expansion of the game.

Next, based on your experience in your one play-through, the game sounds to me to be altogether too reassuring. The Russians lack sustainable depth, but NATO lacks the firepower to win (the Americans would be wholly consumed in the very PacWar that would create the vacuum the Russians would be exploiting; victory in Europe would depend on the Germans, who have gone totally AWOL). Beyond that, based on the unclas reporting I see, the Russians will own the electromagnetic spectrum. Moreover, contrary to what the game shows, I fear that Russian Morale, Will & Cohesion (MorWilCo, I call it), will decisively prevail over that of the West, at least for the first year of any such war. Our peacetime military has subordinated military to political matters while the Russians have intensively remilitarized. While they have learned from Stalin’s catastrophic purges, we’ll be replaying Kasserine and Savo Island at the outset and will have to replay the purges of depoliticization and remilitarization that converted the US officer corps from losers in 1941-42 to winners in 1944-45.

And on that cheery note, I bid you good health! Tim

Mr. Ian Sullivan responded with the following comment for Tim Smith:

“So nice to hear from you Tim! It’s been a VERY long time! And thank you for the comments. I’m grateful to see that the Mad Scientist blog gets readership from the Navy.

I really appreciate the comments. So I was nowhere near as ambitious as Dr. Lacey, who played a massive global version involving three of the games; one focusing on Baltics/Poland, one on Taiwan, and one on Korea simultaneously. My Florida Room is not nearly big enough for that kind of a table!

And you’re right about Poland as a “sand box.” The game pushes the conflict into a more narrow focus. Strategically, I believe the Joint Force is far more capable when we avoid a narrow focus, but that’s neither here nor there. But again, I didn’t really intend to play the game to simulate reality. I played it as more of a key assumptions check on some of our thoughts on contemporary/near-future warfare. And for that, I think it was an interesting experience.

Your comments about the rosy outlook also are very relevant and valid, and again, a cause for concern. The last thing I’d want is for a reader to come away with the idea that a fight against a near-peer pacing threat would be quick and contained. One of the things I’d say is that I almost certainly didn’t “fight” this conflict at anything close to what reality would be. The outcome probably was rosy, in terms of length of the conflict and the decisive nature of the outcome. But I wasn’t trying to focus on that. For what it’s worth I actually just finished playing the Taiwan game, and your points about Savo Island and Kasserine are apt.

I recognized one of the dangers in writing about playing a game is that there could be a danger of paying too much attention to what happened in the game instead of using the game as a learning process. The result was interesting to me, but I really wanted to go into it as an opportunity to check assumptions and to see if there is anything we missed. If you haven’t read TRADOC Pamphlet 525-92 “The Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Warfare”, I’d humbly point you to it. I’m working on a update to it, and I wanted to see if there is anything we may have missed, overestimated, or undervalued. This was one way for me to think about those important questions.

So that’s my long-winded answer to your very good points. Thanks again for commenting. I’d love to come hear about what ONI is working on in terms of gaming. Maybe when the pandemic is under control, I could come up for a visit? Take care.”

Roger all! Love the analytic focus in your approach to wargaming. It’s a powerful medium for Key Assumptions Checking and other Heuer/McPherson SATs, including, of course, the ‘what-ifs’ AH & SPI emphasized from the outset back in the 1960s. As Peter Perla has made so clear, wargaming proves nothing, but if approached analytically, can add tremendous value in challenging assumptions, highlighting otherwise obscure causal relationships, and offering insight during initial stages in the exploration of alternatives. Not to mention training.

I’ll take a look at the TRADOC doc.

Would love to host you. We could follow up via NIPR. Let me offer you my home email: StrategyGaming21@gmail.com (naturally!). From there we can move to NIPR.

Til then, Tim

An game-related internship opportunity for graduate students from the Wilson Center…

THE SERIOUS GAMES INITIATIVE INTERNSHIP

We are seeking a research intern for the Science and Technology Innovation Program’s Serious Games Initiative, reporting to the Director of SGI.

About the Program

As a dominate form of media used by the average American, games have the power to make complex ideas accessible, allowing a direct experience to worth through the intricacies of policy problems. The Serious Games Initiative (SGI) was founded with one goal: to use games to engage the broader public in policy discourse. It is one thing to read about potential impact of policy solutions – it is another to live it. Since its founding, SGI has been a leader in the field of serious games. Under the umbrella of the Science and Technology Innovation Program, SGI is using games as a dynamic technology to communicate cutting edge research at the Wilson Center and beyond.

The primary responsibilities of this internship would be:

Write or edit articles for either peer-reviewed or popular media, such as blog posts amplifying the applications of serious games for policy initiatives.

Conduct background policy research to support game development.

Support meetings for game-based working groups, conferences, and other events, gaining valuable project management experience.

Successful applicants should:

Have a demonstrated background in policy or social science research, and a demonstrated interest in the positive impacts of games, such as serious games, game-based learning, or sociological orientations to game communities.

Excel at writing for mixed audiences, with particular preference given to candidates with background in writing academic and popular media (blog) styles.

Be detail-oriented.

Be able to work remotely.

Be enrolled in a degree program, recently graduated (within the last year) and/or have been accepted to enter an advanced degree program within the next year.

This is an unpaid position available for 15-20 hours a week for undergraduate and graduate-level students. Applicants from any fields will be considered. Experience conducting cross and trans-disciplinary research is an asset

Ian, I don’t know if long-delayed follow-ups pop up in your email queue, but here’s a question: based on what we’ve seen so far during the current Russian aggression, how accurately do you think ‘Next War: Poland’ quantifies Russian and NATO capabilities, weaknesses and vulnerabilities?

Stay well!