[Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist Laboratory is pleased to feature guest blogger and proclaimed Mad Scientist Caroline Duckworth‘s post addressing one of humankind’s most essential commodities — clean water — and the associated ramifications that future shortages will have on the Operational Environment. Per the Military Health System’s official website, “men should consume about 100 ounces of fluid (3 liters) each day, and women should aim for about 70 ounces (2 liters) for baseline hydration. In hot and humid environments and during physical activity, more is needed to maintain hydration — about one ounce per pound of body weight.” The standard planning factor per Soldier increases to 7.9 gallons of water per day in arid environments when one factors in personal hygiene, field feeding, heat injury treatment, and vehicle maintenance. Ms. Duckworth explores the future global challenges in accessing adequate supplies of this precious commodity, the associated potential of water shortages to destabilize regions and generate future conflict, and its implications for future Army operations. Enjoy! (Note: Some of the embedded links in this post are best accessed using non-DoD networks.)]

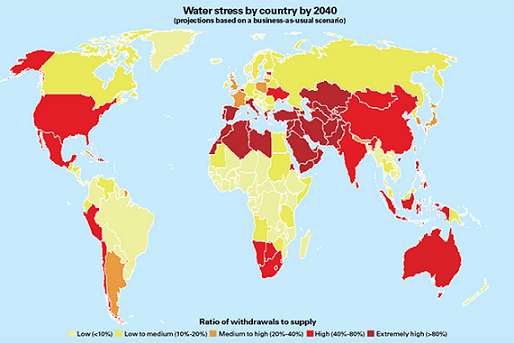

In less than 30 years, rising populations, increased urbanization, and climate change will cause 25% of the planet to face serious drought and desertification. While this trend will create significant problems for world leaders and governments, water shortages also will create unique challenges for the Army. As a result, the future Operational Environment will entail new areas for instability, shifting geopolitical rivalries, and strained Army logistics.

Water Wars

Increased water scarcity may lead to conflict that will require Army intervention. While armed conflict rarely starts solely over water, water has been acknowledged as a contributing factor in conflict, and has been repeatedly weaponized or targeted as a tool of warfare. Data collected from the Pacific Institute demonstrates that the use of water as a trigger, weapon, or target in warfare has been increasing, and has even been targeted by non-state actors.

Many countries and regions of interest to the United States will be threatened by the violence associated with water scarcity. For instance, Iran’s geography and poor environmental management will increase its water stress to critical levels in the next ten years.1 Already, dozens have been killed and thousands arrested in response to protests over water pricing and rationing in the country. If left unchecked, former Iranian agriculture minister, Issa Kalantaria, predicts that water scarcity could drive 50 million Iranians to leave the country. Water stress of this magnitude, combined with the regional drying effects of climate change in neighboring countries, could result in a devastating and destabilizing regional refugee crisis, as families search for new sources of this critical resource. Non-state actors could further exploit this situation, relying on the chaotic environment to recruit vulnerable populations and pursue their goals.

Iran is not the only country facing migration as a result of water scarcity. UNESCO states that water scarcity reduces food security. When combined with factors such as political instability, poor governance, and poor job opportunities, families turn to migration. In fact, migration catalyzed by water stress is recognized as a stronger predictor of permanent migration than flooding or natural disaster. Twelve out of 17 of the most water-stressed countries are located in the Middle East and North Africa. However, India, too, faces significant water challenges, ranking 13th for water stress with “more than three times the population of the other 17 extremely highly stressed countries combined.” By 2030, water demand in India will be double the supply, and severe water scarcity could cause a 6% loss in GDP. Should governance and environmental management not adequately address these problems, these countries could face a massive exodus, straining humanitarian assistance in MENA and Southeast Asia. This type of crisis would increase regional instability, threaten U.S. Army missions overseas, and could strain DoD resources by requiring more water-related humanitarian assistance abroad.

As water becomes scarcer and increases in value as a strategic asset, non-state actors may also be more likely to target water sources. Targeting of water is already increasing, with water-related terrorism rising 263% from 1970 to 2016. The Islamic State has targeted water supplies in Syria and Iraq by “diverting water, flooding communities, contaminating water sources, threatening destruction of dams, and controlling water only to sell it back to the governments and populations in the region.” Al Shabab has similarly sought to take advantage of drought in Somalia by targeting those displaced by water scarcity for recruitment. The increasing scarcity of this essential resource will increase its attractiveness to non-state actors seeking leverage.

While states are more likely to cooperate over water than fight over it, research demonstrates that water-related disputes, particularly at the subnational level, are increasing. In these cases, water scarcity amplifies problems of poor governance and infrastructure and contributes to instability.

However, there are still notable cases of international conflict and tension over water resources. For instance, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan have argued over shared water resources for decades, and at various times used shared resources as political leverage. Notably, China has been accused of holding back large volumes of water in the Mekong River from downstream countries as a political tool, causing record low water levels in Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam.

As the Army becomes involved in regions marred by water conflict and scarcity, it will be unable to continue sourcing water from local populations without dangerous repercussions. For instance, the Army’s capacity to locally procure water could undermine hearts and minds campaigns by promoting tension with local populations over scarce resources. Army use of water in stressed areas could also support perceptions of colonization or imperialism on behalf of the United States, undermining support for Army missions. Adversaries could even weaponize the narrative of exploitation, highlighting U.S. military use in water poor areas. However, should the military succeed in developing efficient and sustainable water collection technologies, the Army could mitigate water scarcity and promote stability within the regions it operates. The provisions of essential resources as a measure of goodwill could increase support for Army involvement in complicated conflicts.

Changing Tides of Power

Water stress will affect states’ resources and their ability to complete foreign policy objectives. In many cases, domestic water challenges have constrained state resources and promoted internal conflict. Water scarcity is likely to affect the United States and its pacing threats differently, contributing to changes in global power. While other forces are likely to mitigate these shifts, extreme water stress or excess may create unexpected changes in power.

-

-

- United States: The U.S. Southwest is facing a hotter and drier climate, and expects an increase in both severe droughts and floods. The frequency and intensity of dry spells are expected to increase across the country, and the Western United States is threatened by an impending “megadrought.” These trends could necessitate changes in food production, which currently accounts for 70% of total water use. Domestic water scarcity trends could also exacerbate water threats to U.S. military

bases (e.g., Forts Irwin, Huachuca, Bliss, Hood), which the Army already recognizes as threatened. The United States will be forced to mobilize more resources to address these challenges, which could delay modernization and reduce readiness of the U.S. military. Further, domestic unrest due to water stress – similar to protests over poor government management of the water crisis in Flint, Michigan – could lead to the deployment of the National Guard, again diverting the attention of the military.

bases (e.g., Forts Irwin, Huachuca, Bliss, Hood), which the Army already recognizes as threatened. The United States will be forced to mobilize more resources to address these challenges, which could delay modernization and reduce readiness of the U.S. military. Further, domestic unrest due to water stress – similar to protests over poor government management of the water crisis in Flint, Michigan – could lead to the deployment of the National Guard, again diverting the attention of the military.

- United States: The U.S. Southwest is facing a hotter and drier climate, and expects an increase in both severe droughts and floods. The frequency and intensity of dry spells are expected to increase across the country, and the Western United States is threatened by an impending “megadrought.” These trends could necessitate changes in food production, which currently accounts for 70% of total water use. Domestic water scarcity trends could also exacerbate water threats to U.S. military

-

-

-

- China: Pollution and regional scarcity increase water inequality for Chinese citizens. The water available per capita in China is only ¼ of the global average, and this disparity is likely to persist given Chinese trends toward urbanization and population growth. While China has made efforts

Water pollution in China / Source: Flickr, Photo by James Chen since 2001 to address water pollution, 200 million in the country still depend on unsafe water sources. In some cases, water emergencies have led to unrest in rural areas. Thus, China’s water challenges are likely to affect it similarly to the United States, directing attention and funding inwards. Global water scarcity could also increase negative perceptions of the Belt and Road Initiative, which is already criticized for polluting water resources and attempting to control strategic areas, like the Horn of Africa, through water projects.

- China: Pollution and regional scarcity increase water inequality for Chinese citizens. The water available per capita in China is only ¼ of the global average, and this disparity is likely to persist given Chinese trends toward urbanization and population growth. While China has made efforts

-

-

-

- Russia: Although unevenly distributed and of low quality, Russian renewable water resources amount to 10% of world river flow. Melting tundra, as a result of climate change, could increase the amount of water available to Russia, and subsequently increase power production via hydroelectricity, should Russia effectively manage these flows. Already, countries facing droughts buy land in water-rich countries to support water-intensive crops. In the future, Russia could become a site for countries seeking those

Wheat / Source: Flickr, Photo by Andrew Gustar via Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic services. This trend will be amplified as climate change enhances Russia’s ability to grow wheat by extending growing seasons and increasing Russian arable land. Thus, in an age of water scarcity, Russia may actually benefit, with more energy and funds to be devoted to non-water projects. Russia could even leverage its relative plenty to forge new partnerships with water-poor countries.

- Russia: Although unevenly distributed and of low quality, Russian renewable water resources amount to 10% of world river flow. Melting tundra, as a result of climate change, could increase the amount of water available to Russia, and subsequently increase power production via hydroelectricity, should Russia effectively manage these flows. Already, countries facing droughts buy land in water-rich countries to support water-intensive crops. In the future, Russia could become a site for countries seeking those

-

Army Logistics

The Army already acknowledges its over reliance on bottled water, and more than 100 military bases are currently at risk of water shortages. This challenge, combined with global salt water intrusion, will stress the Army’s ability to procure water for drinking, weapons testing (e.g., using weapons underwater), fire suppression, and sanitation.

While abroad, the Army is usually able to source a portion of its water from the local area. For instance, in Afghanistan, the military built wells to supply water for non-drinking purposes. However, such an arrangement may not be a viable option in the future given global water shortages. Instead, the Army may be required to externally source and transport even more of its water, creating a massive logistical challenge.

To supply more of its own water, the Army is turning to novel technologies. Currently, the Army purifies natural water sources via reverse osmosis. However, this technology faces logistical and maintenance burdens and requires a power source, making it undesirable in missions where electrical signals are unwanted. Passive capture techniques, such as condensation tarps, are similarly unattractive, as they must be large, and therefore noticeable, to effectively collect water.2

- The DoD is proactively seeking to address these shortcomings by developing technology for atmospheric water extraction and soliciting alternative design submissions from the private sector. The current prototype technologies are often still heavy, require power, and need to be run constantly to generate enough water, making them similar to currently fielded methods.3 However, the DoD hopes to innovate past these weaknesses to create new sustainable water sources.

Should new approaches succeed, there is also concern that the Army’s ability to secure water in a scarce region could provide a target for enemy combatants. Transport lines, water reservoirs, and water technology may become targets for attack for dissenters. Even in cases where the water is not owned by the military, the Army may still be needed to protect those resources as part of its mission, similar to COIN protection of oil assets. Already, the U.S. Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine published a document on emergency response for threats against military water systems. Increased water scarcity could make these more attractive targets for those seeking to disrupt U.S. military operations.

Closing

The problem of water scarcity poses a three-fold challenge to the U.S. military. As a result, the DoD and the Army have a unique position to lead the world in addressing the challenge of water scarcity. By working to invest in water harnessing technologies, adapting protocols to be more water efficient, and identifying which locations – domestically and internationally – will struggle the most with water scarcity, the Army can turn this challenge into an opportunity to further growth and resilience. By leveraging efficient water collection technology, the Army could provide a stabilizing hand in unstable regions, mitigating the effects of water scarcity on migration and unrest.

If you enjoyed this post, check out:

GEN Z and the OE: 2020 Final Findings to read a synopsis of Caroline Duckworth‘s Project on International Peace and Security (PIPS) white paper, CLASHING CODES OF CONDUCT Asymmetric Ethics and the Biotech Revolution, access her paper, and watch her video presentation.

Emergent Global Trends Impacting on the Future Operational Environment

Climate Change as a Threat Multiplier: Part 1, by LTCOL Nathan Pierpoint, Australian Army

Climate Change Laid Bare: Why We Need To Act Now, by Sage Miller

Extended Trends Impacting the Future Operational Environment

>>> REMINDER 1: The Mad Scientist Initiative will facilitate the next webinar in our Weaponized Information Virtual Events series this Wednesday, 15 July 2020:

>>> REMINDER 1: The Mad Scientist Initiative will facilitate the next webinar in our Weaponized Information Virtual Events series this Wednesday, 15 July 2020:

AI Speeding Up Disinformation — This virtual panel will be moderated by LTG John D. Bansemer (USAF-Ret.), and will feature Dr. Margarita Konaev, Katerina Sedova, and Tim Hwang, all from Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technologies.

In order to participate in this virtual webinar, you must first register here [via a non-DoD network].

>>> REMINDER 2: We will facilitate our Weaponized Information Virtual Conference, co-sponsored by Georgetown University and the Center for Advanced Red Teaming, University at Albany, SUNY, on Tuesday, 21 July 2020. The draft agenda for this event can be viewed here. In order to participate in this virtual conference, you must first register here [via a non-DoD network].

>>> REMINDER 3: If you missed participating in any of the previous webinars in our Mad Scientist Weaponized Information Virtual Events series — no worries! You can watch them again here [via a non-DoD network] and explore all of the associated content (presenter biographies, slide decks, scenarios, and notes from each of the presentations) here.

Caroline Duckworth is a rising senior at The College of William and Mary in Virginia, studying International Relations and Data Science. She is currently interning with the Mad Scientist Initiative through the Army Futures and Concepts Center. Caroline is a proclaimed Mad Scientist, having previously presented her white paper, “Clashing Codes of Conduct: Asymmetric Ethics and the Biotech Revolution,” at the Mad Scientist GEN Z and OE Conference.

Special recognition belongs to Ms. Damarys Acevedo-Mackey, Ms. Kayla Cotterman, Mr. David Kolleda, MAJ Brad Mejean, Professor Robert Norton, and Professor Ben Ruddell for their guidance and knowledge on this topic.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command, or the Training and Doctrine Command.