[Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist Laboratory welcomes today’s guest blogger Heather Venable and her timely and insightful post on how creativity is the sine qua non for disruptive strategic thinking. An enduring tension exists between entrenched interests and truly innovative ideas. Creativity, and a willingness to disregard precedent, is what sets apart change agents (like BG William “Billy” Mitchell, pictured above); enabling them to overcome the inherent resistance to new and innovative warfighting technologies and concepts. The U.S. Army is at a historical inflection point — we must seek out and heed our creative disruptive strategic thinkers to spawn an overarching strategic vision that will guide our way ahead. Anything less condemns us to preparing to fight the last war, not the next! (Note: Some of the embedded links in this post are best accessed using non-DoD networks.)]

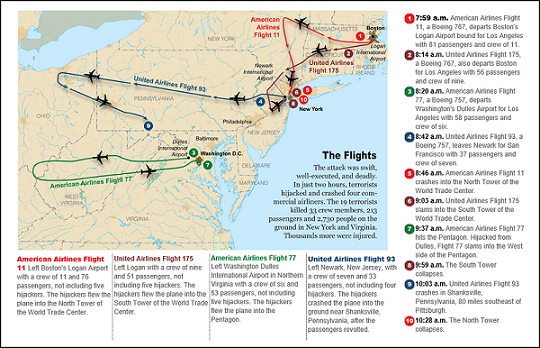

I sometimes begin teaching an airpower class by asking students to compile a list of the most strategically effective uses of airpower. Responses tend to range from the Battle of Britain to Normandy to Desert Storm. Occasionally a student will even cite a compelling example of non-kinetic airpower, such as the Berlin Airlift. To this list I like to add a different example: the use of four civilian airliners against the United States on September 11, 2001. The strategic effect of this relatively inexpensive and asymmetric use of force has been vast, to include resulting in ten percent of the nation’s national debt.1

But the U.S. tends to think more conventionally about future conflict, in part because it has been able to rest on technological superiority for so long. Now, though, it must think differently. Isaac Asimov offers a path toward new strategic solutions through creativity, a process that can be mastered by “becoming dissatisfied” with the current state of “knowledge” and then “rejecting” some or all of it for new approaches.2 In other words, the essence of creativity is thinking differently.

But the U.S. tends to think more conventionally about future conflict, in part because it has been able to rest on technological superiority for so long. Now, though, it must think differently. Isaac Asimov offers a path toward new strategic solutions through creativity, a process that can be mastered by “becoming dissatisfied” with the current state of “knowledge” and then “rejecting” some or all of it for new approaches.2 In other words, the essence of creativity is thinking differently.

Truly creative thinking can be difficult to find. The defense community recognizes creativity’s importance in theory, but it has not fostered it in practice. One commentator, for example, recently called for the military to develop “creative solutions” to acquire new technology, citing the example of a “commercial cloud.” But this idea is not new at all, thus demonstrating how the word is thrown around without much reflection.3 A technical rationalist mindset, moreover, pervades much of the Department of Defense (DOD), with cursory mentions of creativity predominantly linked to inventing new products.

Innovation continually underperforms in part because it is the follow-on to ideas, not the precursor, and because it results in solutions for the tactical level of war. Previous eras of transformational change, however, required societies to tackle “primarily intellectual, not technical” challenges.4 Placing too much emphasis on what to fight with results in a lack of knowledge of how to fight or to what end. The National Defense Strategy epitomizes this trend at times, explaining that “success no longer goes to the country that develops a new fighting technology first, but rather to the one that better integrates it and adapts its way of fighting.” This comment diverges only slightly from traditional technological determinism, asserting that how one integrates technology into its organization determines who wins.5

Innovation continually underperforms in part because it is the follow-on to ideas, not the precursor, and because it results in solutions for the tactical level of war. Previous eras of transformational change, however, required societies to tackle “primarily intellectual, not technical” challenges.4 Placing too much emphasis on what to fight with results in a lack of knowledge of how to fight or to what end. The National Defense Strategy epitomizes this trend at times, explaining that “success no longer goes to the country that develops a new fighting technology first, but rather to the one that better integrates it and adapts its way of fighting.” This comment diverges only slightly from traditional technological determinism, asserting that how one integrates technology into its organization determines who wins.5

Those responsible for crafting U.S. strategy must foster new ways of thinking to challenge the nation’s current strategic paradigm.6 Although the U.S. military acknowledges this need—recognizing that peer adversaries have been studying its successes since Operation Desert Storm—it has not figured out how to change the rules of the game because of “functional fixedness,” or the process whereby cognitive bias “limits the way we use an object to what it was originally intended for and keeps us from seeking new usages.”7 This way of thinking helps to explain why IBM, for example, did not “invent the personal computer.” Repeatedly we see institutions and organizations struggle to reject aspects of their past success in order to embrace asymmetric, transformative advantages and thinking.8

Take Multi-Domain Operations as an example. The Army and Air Force’s newest solution to future warfighting has striking overlaps with its predecessor AirLand Battle.9 It seeks to improve upon Jointness, even as it exacerbates the communication requirements that constitute the nation’s warfighting Achilles heel.10 It provides evolutionary improvements but no shift in strategy because the military feels more comfortable focusing on operational solutions.11

Take Multi-Domain Operations as an example. The Army and Air Force’s newest solution to future warfighting has striking overlaps with its predecessor AirLand Battle.9 It seeks to improve upon Jointness, even as it exacerbates the communication requirements that constitute the nation’s warfighting Achilles heel.10 It provides evolutionary improvements but no shift in strategy because the military feels more comfortable focusing on operational solutions.11

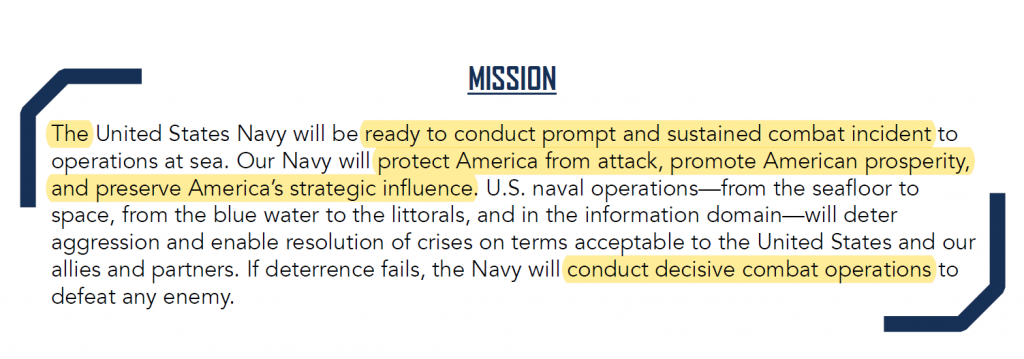

This approach characterizes the U.S. military’s tendency over the last decades as a “continuous movement away from the political objectives of war toward a focus on killing and destroying things,” as epitomized by the current emphasis on lethality.12 This propensity can be seen in the Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority 2.0’s mission statement (see Figure 1, below). Currently, the mission statement sandwiches hints of a holistic naval strategy between “prompt and sustained combat” and “decisive combat operations.” Those operational and tactical tasks go last, not first and last.

One of the easiest ways to facilitate the transformative and creative process is to locate strategists on cultural fault lines because they trigger new ways of seeing and understanding, which helps them envision how to change the rules of the game rather than reacting to what others do. As Everett Dolman explains:

When confronted with an unbreakable logic, such as the paper-scissors-rock dilemma of the Swiss pike, which is superior to the French cavalry, which is superior to the Spanish tercio, which is superior to the Swiss pike, ad infinitum, the only way out is to move beyond the conundrum and change the rules of the game.14

This problem is made more challenging by differences in perspective between tactical thinkers and strategic ones.15 A tactical thinker concentrates on the short-term prospect of winning a clear-cut victory. A strategic thinker, by contrast, plays the long game, continually asking “then what?” At times, these two perspectives exist in tension. In the case of a father who wants to teach his daughter how to play chess, the tactical mindset of seeking to “win” a game sits at odds with the more strategic perspective of ensuring that the father does not extinguish the daughter’s motivation to learn when she keeps losing.16

The Department of Defense has embraced innovation. It is time to do the same for ideas, not just to produce the latest weapons technology but to provide an overarching strategic vision for where we want and need to go. Until then, we will continue preparing mostly to fight the last war, not the next one.

If you enjoyed this post, please see:

– Making the Future More Personal: The Oft-Forgotten Human Driver in Future’s Analysis and The Changing Dynamics of Innovation, by Mr. Ian Sullivan

– The entire Mad Scientist Disruption and the Operational Environment Conference Final Report, dated 25 July 2019.

– Former Deputy Secretary of Defense, Mr. Bob Work‘s presentation from the aforementioned conference on AI and Future Warfare: The Rise of the Robots (and Army Futures Command), as well as his Modern War Institute podcast assessing the future battlefield.

Heather Venable is an assistant professor of military and security studies at the U.S. Air Command and Staff College and teaches in the Department of Airpower. She has written a forthcoming book entitled How the Few Became the Proud: Crafting the Marine Corps Mystique, 1874-1918.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Air Force, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

1 Kimberly Amadeo, “War on Terror Facts, Costs, and Timeline,” 25 June 2019, https://www.thebalance.com/war-on-terror-facts-costs-timeline-3306300.

2 Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention (New York: Harper, 2013), 90.

3 VADM T.J. White, RDML Danelle Barrett, and LCDR Robert Bebber, “The Future of Information Combat Power: Winning the Information War,” 14 March 2019, http://cimsec.org/the-future-of-information-combat-power-winning-the-information-war/39934?fbclid=IwAR3DF3vZthb_ipk1A57Uih7Vz1yht1_i9QBuDESLHzcZ8OtcOSl8Oh5i398.

4 Quoted in Dave Lyle, “Fifth Generation Warfare and Other Myths: Clarifying Muddled Thinking in Our Current Defense Debates,” 4 Dec 2017, https://othjournal.com/2017/12/04/fifth-generation-warfare-and-other-myths-clarifying-muddled-thinking-in-our-current-defense-debates/. For more on the failure to innovate organizationally, see Lt. Gen. Michael G. Dana, “Future War: Not Back to the Future,” 6 Mar 2019, War on the Rocks; https://warontherocks.com/2019/03/future-war-not-back-to-the-future/.

5 Quoted in Zachery Tyson Brown, “All This ‘Innovation’ Won’t Save the Pentagon,” 23 April 2019, https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2019/04/all-innovation-wont-save-pentagon/156487/.

6 See James A. Russell, James J. Wirtz, Donald Abenheim, Thomas-Durrell Young, and Diana Wueger, Navy Strategy Development: Strategy in the 21st Century, June 2015, 4; https://news.usni.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/NPS-Strategy-Report-Final-June-16-2015-2.pdf#viewer.action=download.

7 Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority, Version 2.0, December 2018, 3, available online at https://news.usni.org/2018/12/17/design-maintaining-maritime-superiority-2-0; Scott Kaufman and Carolyn Gregoire, Wired to Create: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Creative Mind (New York: Tarcher Perigee, 2016), 182.

8 Wired to Create, 95.

9 See, for example, Colin Clark, “Army Unveils Multi-Domain Concept; Joined at Hip with Air Force,” 10 Oct 2018, Breaking Defense, https://breakingdefense.com/2018/10/army-unveils-multi-domain-concept-joined-at-hip-with-air-force/.

10 See, for example, Jacquelyn Schneider, “Digitally-Enabled Warfare: The Capability-Vulnerability Paradox,” 29 Aug 2016, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/digitally-enabled-warfare-the-capability-vulnerability-paradox.

11 See, for example, LTC Antulio J. Echevarria II, “An American Way of War or Way of Battle,” Parameters, 1 January 2004, https://ssi.armywarcollege.edu/pubs/display.cfm?pubID=662.

12 Frederick Kagan, Finding the Target (New York: Encounter Books, 2006), 358; Peter Haynes, Toward a New Maritime Strategy: American Naval Thinking in the Post-Cold War Era (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2015), 5.

13 Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority, Version 2.0, December 2018, 1.

14 For an example from the popular movie Princess Bride that Dolman discusses as well, see Mark McNeilly, “’The Princess Bride’ and the Man in Black’s Lessons in Competitive Strategy,” 2 October 2012, https://www.fastcompany.com/3001732/princess-bride-and-man-blacks-lessons-competitive-strategy.

15 Everett Carl Dolman, “Seeking Strategy” in Strategy: Context and Adaptation from Archidamus to Airpower. Eds. Richard Bailey and James Forsyth (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2016), 5-37.

16 Dolman, “Seeking Strategy,” 18.