[Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist Laboratory is pleased to publish today’s post by guest blogger and proclaimed Mad Scientist Zachery Tyson Brown, addressing how the advent of swarming networked weapon systems will facilitate the renaissance of the 19th Century strategist Baron Antoine-Henri de Jomini‘s concept of mass, enabling future battle commanders to disperse their combat assets for maneuver and then concentrate them for massed attacks at critical and decisive points. Enjoy! (Note: Some of the embedded links in this post are best accessed using non-DoD networks.)]

“Quantity has a quality all its own.”

“Quantity has a quality all its own.”

– attributed to Joseph Stalin

There’s a great scene in the otherwise unremarkable (Sorry, but it’s just #NotMyStarTrek) film Star Trek Beyond where—spoiler alert!—the USS Enterprise is annihilated by a swarm of thousands of tiny alien ships. As the swarm approaches, Captain Kirk orders defensive measures, while his stoic science officer Spock warns, “Captain, we are not equipped for this manner of engagement.”

Spock’s analysis is right, as usual. The Enterprise’s advanced phaser weapons and photon torpedoes prove useless against the swarm, and its energy shields—designed to deflect energy blasts, not kinetic projectiles—irrelevant. The swarm tears the Enterprise to pieces.

Science fiction, right?

Star Trek Beyond premiered in the summer of 2016, at the height of the U.S.-led campaign to destroy the terrorist group ISIS in Iraq and Syria. At the time, coalition forces were practically paralyzed by just the perception of a threat from ISIS’s fleet of do-it-yourself drones armed with grenades dropped like bombs or munitions rigged to explode on impact in kamikaze-style attacks. I say perception because while the number of casualties produced by these systems was relatively few, the angst they caused vulnerable coalition forces made them U.S. Central Command’s top priority.

Star Trek Beyond premiered in the summer of 2016, at the height of the U.S.-led campaign to destroy the terrorist group ISIS in Iraq and Syria. At the time, coalition forces were practically paralyzed by just the perception of a threat from ISIS’s fleet of do-it-yourself drones armed with grenades dropped like bombs or munitions rigged to explode on impact in kamikaze-style attacks. I say perception because while the number of casualties produced by these systems was relatively few, the angst they caused vulnerable coalition forces made them U.S. Central Command’s top priority.

Predicting the future is fraught with risk, and lethal drone swarms may be a stretch—for the moment. One kamikaze drone, as I said, might not do that much damage. But what about thirteen, thirty, or three hundred? Make no mistake: the weaponized drone swarm is coming. So is the missile swarm, the robot swarm, and the submarine swarm.

You don’t have to be Nostradamus to foresee the marriage of swarming technology with the many loitering, semi-autonomous weapons systems that already exist. Parallel advances in diverse fields like semiconductor miniaturization, computer vision, energy storage, and highly energetic materials might combine to make systems like these the most powerful tactical weapons ever deployed.

In the near future, enormous collectives of small, cheap weapons will clash on a grand scale, like medieval armies charging into one another. The actor who exploits these new weapons’ ability to outmaneuver and overwhelm their opponent’s combat formations will gain a tremendous advantage on an increasingly fast-paced and fluid battlefield by being able to effect sudden attacks on narrow fronts that will smash traditional formations.

The legal and moral implications of such capabilities are one concern that has already drawn the attention of ethicists. Here, I’m more interested in how these weapons conform to what we think we understand about warfare. We’ve entered a period of discontinuous change, when the rate of technological development exceeds that of institutions’ ability to adapt. In such periods, competitors experiment widely with emerging technologies because we don’t yet know their best uses.

The great powers, including the United States, China, and Russia, have different strategic cultures informed by unique histories concomitant with varied approaches to research & development, acquisition, and doctrine-writing. Lesser powers are also experimenting with networked weapons, however, and are in some ways advantaged. Today’s open research architecture has rapidly leveled the playing field and gives almost anyone—including ISIS—access to data, algorithms, and commercial systems that can be quickly militarized. These factors will work together to form an unpredictable battlefield over the next quarter-century.

The great powers, including the United States, China, and Russia, have different strategic cultures informed by unique histories concomitant with varied approaches to research & development, acquisition, and doctrine-writing. Lesser powers are also experimenting with networked weapons, however, and are in some ways advantaged. Today’s open research architecture has rapidly leveled the playing field and gives almost anyone—including ISIS—access to data, algorithms, and commercial systems that can be quickly militarized. These factors will work together to form an unpredictable battlefield over the next quarter-century.

by Marc-Charles-Gabriel Gleyre

For all its novelty, the logic of the drone swarm reminds me of a tenet, until recently out of style, proposed by the doyen of modern war himself—Baron Antoine-Henri de Jomini. Jomini and his contemporaries—including rival Carl von Clausewitz—were infatuated with the scientism of the era and adorned their studies with the cutting-edge terms of the day—force, friction, gravity, and more. Jomini took it much farther, though, professing in his Art of War (published 1838), what he claimed were timeless principles of war—formulaic maxims that if followed, would provide a commander the greatest chance of success in battle.

The purpose of Jomini’s principle of mass was to concentrate units at the most advantageous time and place, which should prove decisive. In the Napoleonic Wars, this meant concentrating large numbers of soldiers to assail the weakest or most vulnerable portion of an enemy’s line with overwhelming force.

Jomini’s ideas held sway for a century or more, particularly in America. It was Jomini that American generals on both sides of the Civil War were taught at West Point. They were said to have marched off to war with “sword in one hand and their copy of Jomini in the other.”

Ironically, this period was also the apogee of Jomini’s influence, precisely because of its commanders’ adherence to the maxim of mass. What they didn’t immediately grasp was how the acceleration of the industrial revolution had turned Jomini’s formula for victory into a recipe for wholesale slaughter. Taken to its logical extreme fifty years later during the First World War, massed assaults resulted in unprecedented carnage.

Afterward, armies began to experiment with dispersed formations who could more nimbly maneuver and seek cover and concealment from the mechanized fires of the industrial age. The Second World War and the Korean War certainly had mass engagements, but even in these the trend in combat was towards the application of combat power rather than mass per se, as the lethality of individual weapon systems disproportionately increased.

By the time the United States developed its ‘Second Offset’ strategy in the 1980s, precision and economy of force became the apex of military art. Militaries came to rely upon small numbers of exquisitely sophisticated and exorbitantly expensive capabilities that were also hard to replace—but this didn’t bother us too much at the time. Jomini’s mass—at least in terms of concentrating forces—was decidedly out of style.

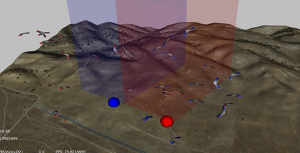

The advent of drone swarming will mark its return, albeit in a different form. The near-instant synchronization of these networked weapons will allow them to disperse for maneuver and concentrate for attacks at critical locations—Jomini’s ‘decisive points’—which is itself reflective of another contemporary, Prussian General Gerhard von Scharnhorst’s maxim to ‘march divided, fight concentrated.’

Small units will be augmented with the ability to employ tens or hundreds of integrated weapons, providing them with far more relative combat power than in the past. They’ll be able to use these small, cheap, and individually expendable platforms to almost continuously gather real-time intelligence and choose the time and place to overwhelm an adversary’s defenses through sheer volume.

These weapon swarms will require planners and operators to design new operating concepts that effectively employ their strengths and mitigate their own vulnerability to counterattack. Commanders will need to be able to conceptualize operations in multiple dimensions and embrace distribution and autonomy. Smaller units vulnerable to saturation attack will need to maintain and employ organic electronic warfare and air defense systems on a large scale, but these may prove limited thanks to the inherent resilience of a networked swarm.

Of course, prognostication is kind of like discerning the shape of a distant mountain shrouded in fog. While it’s impossible to know the path to the summit before we get there, and there will undoubtedly be obstacles and detours along the way, as we draw nearer, we can roughly guess its contours.

The future battlespace will be fluid and dynamic. It will be transformed by the application of novel technologies powered by unprecedented advances in artificial intelligence, automation, human-machine teaming, and robotics that adapt at speeds beyond human comprehension—a concept some have called hyperwar.

But age-old truisms endure; there is strength in numbers.

If you enjoyed this post, please read:

– Ground Warfare in 2050: How It Might Look, and

– The Democratization of Dual Use Technology

Zachery Tyson Brown is a strategic intelligence analyst and U.S. Army veteran who consults for the Office of the Secretary of Defense. He is a member of the Military Writers Guild and his writing has appeared at The Strategy Bridge, War on the Rocks, Defense One, and West Point’s Modern Warfare Institute. He can be found on Twitter @ZaknafienDC

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

The expression I learned back in HS math class continues to be relevant when one adds the last two words and applies it to human endeavors from cyber to kinetic conflict – “the rate of change of the rate of change (is increasing)”. The move to AFC and doing this Mad Scientist activity are great first steps but adversaries all across the world have a vote, and at least in some parts of it our total defensive and offensive apparatus needs to be at least as agile as they are, others more so.

We cannot bring knives to gunfights, or worse, let our population continue to be attacked in the cyber and informational domains without informing them this is happening and what to do about it. There is a spectrum from advertising to propaganda to full-blown information war, and our adversaries are using the principle of mass promulgated through social media against our citizens on a continuous basis. Who in the DoD will step up and give the American population a threat brief? Who will brief the population on the specific and general tactics the adversaries are using to poison and misinform Americans? Leaders give their troops the same endlessly repeated safety briefs every Friday afternoon warning of the dangers of alcohol, driving and domestic abuse, but our citizens receive nothing like this about the attacks they are now and will continue to experience. This must be corrected – our homeland is being attacked yet the population is being left to fend for itself.