[Editor’s Note: Historical analogy is just one of many tools that the Mad Scientist Initiative leverages in exploring the Operational Environment and the changing character of warfare. Today’s guest blogger Peter Brownfeld wields it effectively in exploring the nature of great power competition in the Twenty-first Century, and how best to counter Russia and China’s on-going efforts to erode the United States’ relationship with our allies and international partners. But what lessons does a dusty tome from the era of “I Like Ike,” sock hops, and bodacious tail fins have for us, sixty-plus years on? And what can we glean from it to enhance our Calibrated Force Posture (one of the three core tenets of Multi-Domain Operations) and counter our adversaries’ efforts to tarnish American prestige with our friends and allies around the globe? Read on!]

Emblazoned with “From Russia with Love,” Russian military trucks lumbered north from Rome to Milan this past March to deliver COVID aid to a stricken NATO ally. Moscow’s efforts to sow doubt among American allies through foreign aid and exploit gaps in America’s force structure are not only key parts of its strategy against the Army’s Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) concept, but also a well-honed Cold War strategy. As a result, we have their playbook. And we must study it.

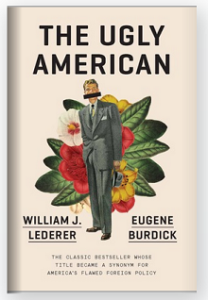

MDO includes a vital role for Army personnel and other USG partners to build a layered stand-off as the US competes short of armed conflict. Some of the terminology may be new, but many of the techniques can be found in the Cold War. With MDO using the pacing threat of Russia, the challenge is evident as Moscow attempts to separate Washington from its partners in Europe and raise questions about America’s commitment to the NATO alliance. The COVID pandemic provides the latest example of how Moscow uses tools of soft power to build its credibility. As the U.S. Army realigns to address these threats to America’s alliances and partnerships, there are some lessons that it can learn from the Cold War classic The Ugly American, by former Navy officers William Lederer and Eugene Burdick.

MDO includes a vital role for Army personnel and other USG partners to build a layered stand-off as the US competes short of armed conflict. Some of the terminology may be new, but many of the techniques can be found in the Cold War. With MDO using the pacing threat of Russia, the challenge is evident as Moscow attempts to separate Washington from its partners in Europe and raise questions about America’s commitment to the NATO alliance. The COVID pandemic provides the latest example of how Moscow uses tools of soft power to build its credibility. As the U.S. Army realigns to address these threats to America’s alliances and partnerships, there are some lessons that it can learn from the Cold War classic The Ugly American, by former Navy officers William Lederer and Eugene Burdick.

In The U.S. Army in Multi-Domain Operations, TRADOC outlines the threat in the following way: Russia and China “attempt to create stand-off through the integration of diplomatic and economic actions, unconventional and information warfare (social media, false narratives, cyber attacks), and the actual or threatened employment of conventional forces.” TRADOC goes on to note that the Joint Force has not kept pace with these developments, and must expand the competitive space through active engagement. If Russia isn’t reading our strategy, it sure looks like it.

As MDO notes, conflict with Russia is most likely to be below the threshold of war, but could also be quick and confusing. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Georgia demonstrated its readiness for armed conflict. Its “mask diplomacy” in Europe and its effective use of cultural tools, particularly in Eastern Europe, show that it is constantly improving its foxhole as it seeks to separate us from our allies and partners. America’s tools are often different—large scale military exercises and high-level visits—but there are also a range of low-cost tools that can be used to great effect: military bands or quartets, school visits, and volunteer activities. Successful use of these tools is indispensable, not only to prevent Russian attempts to erode NATO, but also to build a common commitment that will be necessary if the alliance is to last for the coming decades.

First published in 1958, The Ugly American offers lessons for how we can counteract this Russian approach and improve our position. This lively account includes the following authors’ note: “This book is written as fiction; but it is based on fact. The things we write about have, in essence, happened. They have happened not only in Asia, where the story takes place, but throughout the world.” The authors recount an Embassy staffed by an uninspiring political-appointee Ambassador and Americans with little local knowledge or language skills. One fictional local official is quoted, “The Americans, for reasons which are not clear to me, have chosen to send us stupid men as ambassadors.”

In one of the most memorable passages of the book, the well-trained Russian Ambassador cooks up a scheme to gain a propaganda advantage. The fictional Sarkhan nation has been struck by typhoons leading to famine. With the advantage of superior resources, the United States sends 16,000 tons of aid, and planned a media event at the port.  In the meantime, the Russian Ambassador bought five tons of black-market rice and delivered it to the stricken areas. “The five tons of rice which he had brought along with him were all they could find locally. But be patient, he told them, in excellent Sarkhanese; several Russian grain ships would be arriving in a few days with thousands and thousands of tons of rice which would be distributed free.” Then, using his intelligence network, some dirty tricks, and—most importantly—the ineptitude of the U.S. Embassy, the Russian Ambassador successfully managed to take credit for the US grain delivery.

In the meantime, the Russian Ambassador bought five tons of black-market rice and delivered it to the stricken areas. “The five tons of rice which he had brought along with him were all they could find locally. But be patient, he told them, in excellent Sarkhanese; several Russian grain ships would be arriving in a few days with thousands and thousands of tons of rice which would be distributed free.” Then, using his intelligence network, some dirty tricks, and—most importantly—the ineptitude of the U.S. Embassy, the Russian Ambassador successfully managed to take credit for the US grain delivery.

Much of the book focuses on anti-Communism foreign development, and the limited successes scored by the U.S. Government under the looming cloud of the Vietnam War. The authors outline many of the issues that persist in American foreign affairs, including the weaknesses in the way embassies are organized and staffed, Americans’ limited language skills, and unhelpful attitudes towards foreigners. The book also highlights countervailing examples of excellence both in the military and the State Department. The authors illustrate stereotypes from Embassy life; anyone who has served in an Embassy knows that, unfortunately, many of these stereotypes still exist. The authors close their book with some recommendations: “What we need is a small force of well-trained, well-chosen, hard-working, and dedicated professionals. . . . They must go equipped to apply a positive policy promulgated by a clear-thinking government.”

The U.S. Government has far fewer Americans employed overseas than the hundreds of thousands it had in 1958, but their roles remain critical in building the attractive power of America, and fighting against the efforts of adversaries to weaken our alliances and separate us from our partners. In forward-deployed locations in the Middle East and Africa, the partnership between the U.S. Army and the Embassy is indispensable to success. Army commanders must build cultural and linguistic skills in their ranks, and find their most expeditionary colleagues in the Foreign Service with whom to partner to help demonstrate the shared objectives of the United States and the various host nations. Our allies need to see the military effectiveness of our Soldiers, but they must also see that we share the same values and interests.

In our longstanding host nations in Asia and Europe, the Army has the time to focus on setting the theater, but this time must be greedily safeguarded as we execute key leader engagements, Joint training exercises, and goodwill activities with urgency.  The Army can often gain the most strategic effect by working through the Embassy or Consulate. While the Army brings resources to bear, the State Department can bring the media firepower of an Ambassador or Consul General. It can also bring the contacts of the PAO, Political, and Economic sections. In Italy and Slovenia, as we work to set the theater, we always invite our diplomatic colleagues to public events, and often are able to use them as the tools to generate press coverage.

The Army can often gain the most strategic effect by working through the Embassy or Consulate. While the Army brings resources to bear, the State Department can bring the media firepower of an Ambassador or Consul General. It can also bring the contacts of the PAO, Political, and Economic sections. In Italy and Slovenia, as we work to set the theater, we always invite our diplomatic colleagues to public events, and often are able to use them as the tools to generate press coverage.

It is beyond the scope of this blog post to attempt a full playbook for our Foreign Service colleagues, Foreign Area Officer Corps, and service members of all types overseas. However, The Ugly American should be required reading for those who serve overseas and want to reinforce America’s position for the coming decades by strengthening our relationships and rebuffing our adversaries’ entreaties to sow doubts about American strength or commitment.

It is beyond the scope of this blog post to attempt a full playbook for our Foreign Service colleagues, Foreign Area Officer Corps, and service members of all types overseas. However, The Ugly American should be required reading for those who serve overseas and want to reinforce America’s position for the coming decades by strengthening our relationships and rebuffing our adversaries’ entreaties to sow doubts about American strength or commitment.

If you enjoyed this post, check out the following:

Our two posts on Russia and China as our current and emergent pacing threats.

Blurring Lines Between Competition and Conflict

Persistent Disorder Strikes Back – Implications for Future Joint Force Design, by proclaimed Mad Scientist Jack Becker

Contagion: COVID-19’s impact on the Operational Environment (Part 1) by Chris Elles

Contagion: COVID-19’s impact on the Operational Environment (Part 4) by Ian Sullivan

“Tenth Man” – Challenging our Assumptions about the Operational Environment and Warfare (Part 1)

>>> REMINDER: The Mad Scientist Initiative will facilitate our next webinar on Wednesday, 16 September 2020 (1100-1200 EDT):

The Future of Unmanned Aerial Systems – featuring proclaimed Mad Scientist Mr. Sam Bendett, Advisor, CNA; Mr. Zak Kallenborn, Senior Consultant, ABS Group; and Mr. David Goldstein, Acting Branch Chief for the Precision Targeting & Integration Branch and a Counter- UAS Team Lead, Army Futures Command, Combat Capabilities Development Command, Armaments Center (AFC-CCDC-AC).

The Future of Unmanned Aerial Systems – featuring proclaimed Mad Scientist Mr. Sam Bendett, Advisor, CNA; Mr. Zak Kallenborn, Senior Consultant, ABS Group; and Mr. David Goldstein, Acting Branch Chief for the Precision Targeting & Integration Branch and a Counter- UAS Team Lead, Army Futures Command, Combat Capabilities Development Command, Armaments Center (AFC-CCDC-AC).

In order to participate in this virtual event, you must first register here [via a non-DoD network].

Peter Brownfeld is stationed in Vicenza, Italy, where he serves as the U.S. Army’s Host Nation Advisor for Italy and Slovenia.

Disclaimer: All views expressed here are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, Army Futures Command (AFC), or Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC).